The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

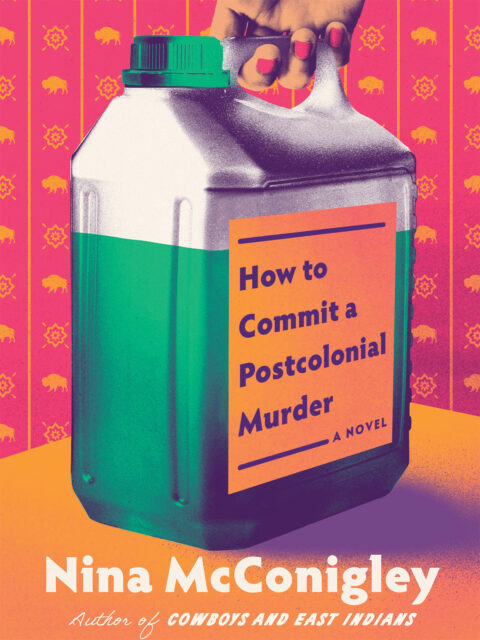

Many writers fantasize about someday publishing a novel or seeing a script come to life onstage. Nina McConigley is about to realize both of those dreams in a single week, with the release of her debut novel, How to Commit a Postcolonial Murder, on January 20 and the opening night of her play, Cowboys and East Indians (adapted from her PEN Award–winning story collection), on January 23 at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts.

The 50-year-old, who is of Indian and Irish descent, was born in Singapore and grew up in Casper, Wyoming. Still, she considers the Mile High City her second childhood home. “I went to Denver once a month as a kid,” says McConigley, whose father worked as a geologist. “It was the closest place we had to get [Indian] groceries.”

When McConigley isn’t teaching her Colorado State University students creative writing, she practices it herself, crafting deeply complex characters and narratives that explore identity, belonging, and immigrant experiences in wide-open, often-overlooked stretches of the American West. Her play, co-written by Matthew Spangler, reframes what it’s like growing up brown in predominately white, oilfield Wyoming, and her novel digs into race, violence, and girlhood.

We chatted with McConigley about the common themes in her latest works and how she’s feeling about sending them into the world.

Editor’s note: The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

5280: How does it feel to debut your work in Denver?

Nina McConigley: In the ninth grade, I saw a Shakespeare play at the Denver Center. It was 1990, or something. I think that girl couldn’t even fathom there would be someone in a sari on the stage of the Denver Center. That would’ve been wild to me.

You’ve described your work as post-frontier writing. What does that mean?

It means reimagining this region and reimagining the stories that come from this region. I think it’s pushing back on the cowboy myth a bit, that everyone sort of carries with them about this place. We’re not all riding horses. I’m telling stories and reinterpreting the West in a way that’s more diverse.

Your characters deal with a lot of serious stuff with humor and wit. Why is that?

I think it’s a little bit of an armor. In fiction, or in a play, you get to fix the thing that you didn’t do when you were living through it. I didn’t have the good comeback, or I didn’t get to change the story. You get to do that with fiction.

Still, your writing holds a lot of empathy for the people committing those bad acts against your main characters.

I think it’s easy to have empathy because they are people who were side by side with me growing up. I get where they’re coming from, in terms of being scared about economics and money and the energy industry. I feel like I’m empathetic to that fear, and I think they’re scared because they want to put food on their tables.

How do you want young people of color to reflect on your work?

My art is my activism. I feel like in writing, I get to again say the things I want to say. I don’t want my daughters to commit a murder, that’s for sure, which my characters do. But I hope they’ll see [the novel] as a way of working through the world.

Read More: 12 Easy Ways To Support the Local Arts Scene