The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

In the second half of the 20th century, the celebrated architect I.M. Pei built three projects in Colorado. His 1961 Mesa Laboratory at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) remains one of his most important works, still standing intact and unmarred on a hill south of Boulder. But Denver virtually erased Pei’s legacy as it allowed developers to disfigure and scar the places he designed here, a topic that continues to anger many.

Pei, who is known for the glass pyramid atop the Louvre, the Bank of China tower in Hong Kong, and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., died May 16 at 102. Around the world, people remembered him for masterful work that applied precise geometric forms to a range of architectural styles.

But here in Denver, you have to squint to see Pei’s spirit in what remains of his buildings.

“Unfortunately, Pei’s legacy has been destroyed,” says Alan Gass, a retired Denver architect who was involved with both the 23-story Mile High Center at 17th Street and Broadway (1953) and Zeckendorf Plaza (1960).

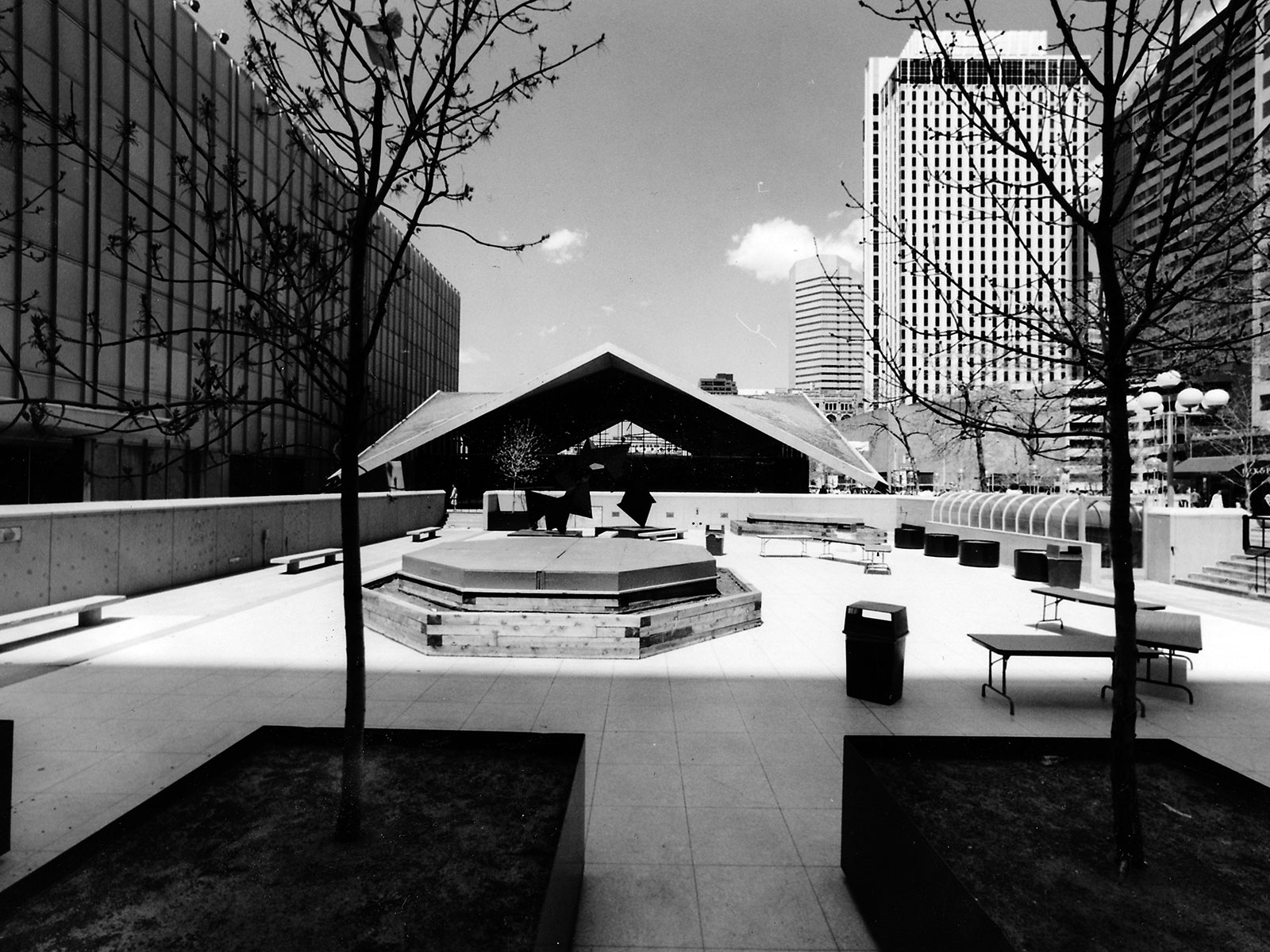

When Zeckendorf Plaza opened, officials touted it as the the Mile High City’s answer to Rockefeller Center. There, the Denver Hilton Hotel opened to a plaza with an ice skating rink, fountains, and the May D&F department store. A pyramidal structure, known as the hyperbolic paraboloid, tied the elements together, serving as a focal point and an alluring entrance to the store.

“This was a suite of buildings designed together,” says Gass. “It was a magnificent thing.”

By the early 1990s, the department store had closed and the building’s owner struggled to lease the space. Desperate to activate a key segment of the 16th Street Mall, officials under the administration of Mayor Wellington Webb allowed hotelier Fred Kummer to take over. Despite the passionate voices of preservationists, he bulldozed the paraboloid, sheathed the department store in shiny black glass, replaced the skating rink with an awkward driveway, and reopened the hotel as the Adam’s Mark (it’s now the Sheraton).

“I.M. Pei’s design was destroyed,” says Gass. “We’re left with third-rate mediocre junk.”

Walking past the Sheraton (pictured below), people can still get a glimpse of Pei’s original design if they tilt their heads upward and look past the ground level. “The only thing of Pei’s design that exists is the skin of the hotel,” says Gass of the modernist grid pattern and the concrete’s rough texture.

Another of Pei’s Denver projects, the Mile High Center, also failed to withstand later development. The 23-story building, which took cues from Mies van der Rohe’s focus on clean, rectilinear lines, featured a carefully designed outdoor plaza that set the building back from the street with open space.

“That building, in its initial form, was 1950s in perfection,” says Amir Ameri, a professor of architecture at the University of Colorado Denver. “It certainly looks back to the work of Mies van der Rohe. Nevertheless, it had its own distinct character.”

But this time, the hand of another architect desecrated Pei’s work. Just across Lincoln Street, Philip Johnson would design the cash register building (1983). Johnson connected the two buildings with a pedestrian bridge and clumsily attached a much too-large glass atrium to Pei’s building. Though Johnson and Pei were friends, the atrium wiped out Pei’s plaza and obscured much of the building. Its eccentric curved forms also clashed with the straight lines and 90-degree angles of Pei’s modernist design.

“It’s almost an assault on the building.” says Ameri. “I’m not sure I can think of another building, or another architect, that would treat the work of a contemporary in quite the same manner.”

But one of Pei’s proudest projects, the Mesa Laboratory, remains untouched by the pressures of urban development. Atop a hill near Boulder, its blocky concrete forms stand out from the Rocky Mountains behind it. Pei drew inspiration from Native American cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde National Park in Southern Colorado, he often said.

“It’s iconic,” says Ameri. “It’s quite incredible in its geometric form.”

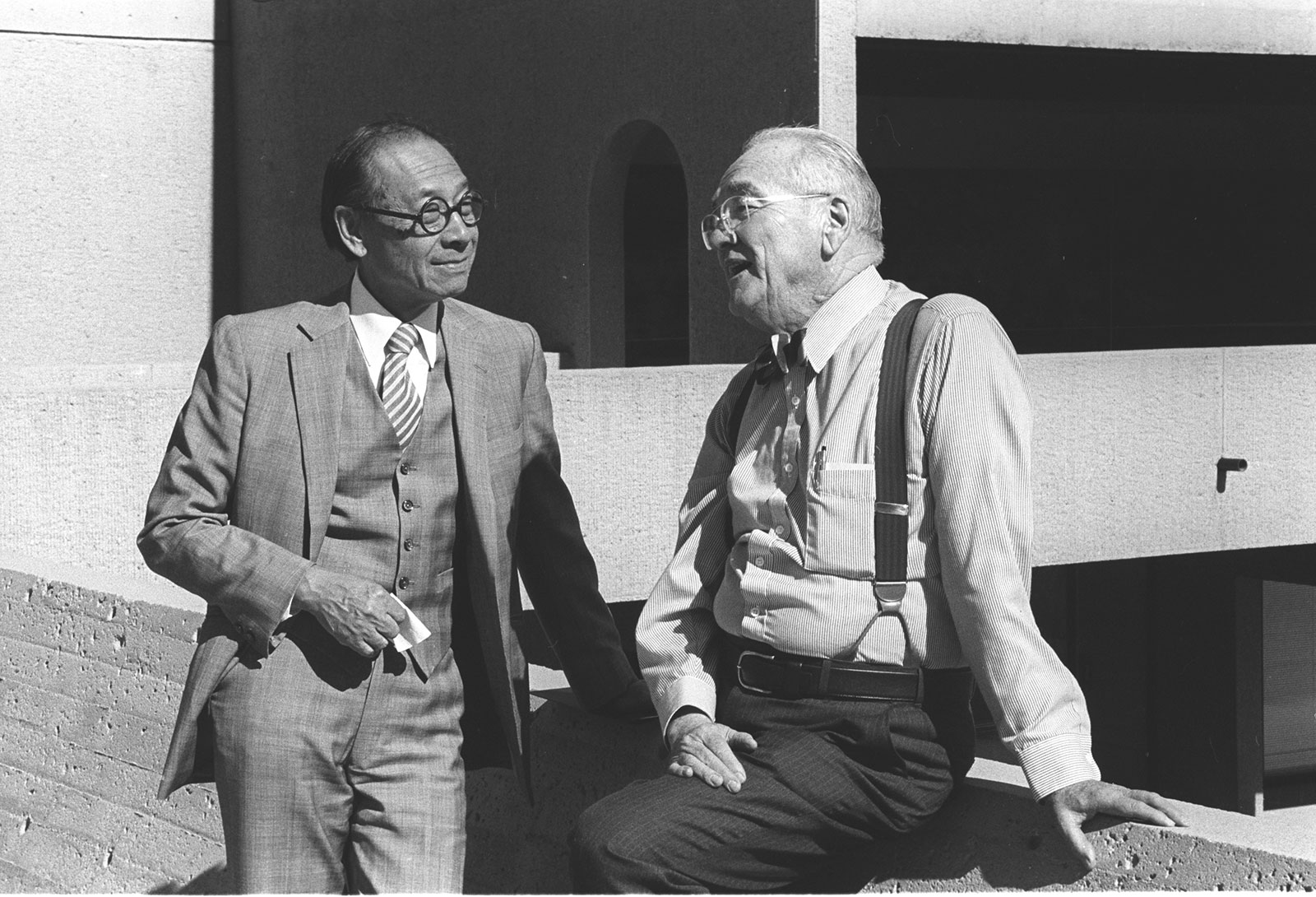

Gass, who visited the architect in the 1990s, said Pei displayed a model of the lab prominently in his New York office. It was one of Pei’s favorite projects, according his business partner, Henry Cobb, who relayed the information to Gass during that trip.

“He was very proud of the NCAR building,” says Gass.

Despite widespread belief, Pei did not design the serpentine tile pattern of the 16th Street Mall. That was left to a design team who worked under Cobb. “Henry Cobb designed a lot of buildings credited to I.M. Pei,” says Gass.

Even with developers stripping Pei’s buildings in Denver of their original grace, Colorado still retains one of the architect’s greatest works.

“Pei’s legacy in Colorado is NCAR,” says Gass. “It’s the only complete Pei design.”

More: You can examine the I.M. Pei’s architecture in person. NCAR welcomes the public to tour its facility.