The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

On December 18, 2023, the state of Colorado invited a group of conservationists, journalists, and politicians to an undisclosed location in Grand County to watch history unfold. Patches of snow dotted the open field, somewhere on state land, and the weather was crisp and clear. Just before 1:30 p.m., Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials unloaded five large, gray aluminum crates from pickup trucks while the roughly 45 onlookers watched.

It took four men, all wearing black jackets and ball caps featuring CPW’s bighorn sheep logo, to carry each cage to its designated spot on the frozen grass. Governor Jared Polis, with first gentleman Marlon Reis smiling at his side, flashed a thumbs-up before bending down to open the first crate. A black snout poked out and sniffed the chilly air.

Wolf 2304 had been captured the day before in Oregon—shot with a tranquilizer dart before being fitted with a GPS collar and loaded into an airplane for the flight south, undergoing multiple veterinary exams along the way. If the 76-pound juvenile female was feeling at all disoriented, it didn’t show. A moment after the governor unlatched her cage, the animal bounded out in a burst of gray and white fur, picking up speed at first and then slowing slightly as she padded toward the copse of aspen, piñon, and spruce trees at the meadow’s edge. The moment 2304 slipped into the woods, followed soon after by four other new arrivals, marked a milestone 80 years in the making. For the first time since the 1940s, gray wolves now roamed free in Colorado.

Wolf advocates who were there described the release in ecstatic, even rapturous terms. “Everybody here is just in reverent awe,” Polis said to a Colorado Public Radio reporter. Fighting through tears, Darlene Kobobel, founder of the Colorado Wolf and Wildlife Center, later told a PBS film crew, “It was the most exciting, beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.” The day was “exquisite in every way,” Joanna Lambert, a conservation biologist and University of Colorado Boulder professor, gushed to the Colorado Sun.

Notably absent, however, were any members of the groups that would be most directly affected by the event: cattle ranchers and Western Slope residents. Rather than characterize the animals’ return as “exciting” or “exquisite,” Tim Ritschard, president of the Middle Park Stockgrowers Association, told the Steamboat Pilot & Today that the result would be “disastrous.”

The vote for Proposition 114, the 2020 statewide ballot measure that mandated the wolves’ return, had broken down fairly neatly along urban-rural lines: 66 percent of Denver County voters were in favor while 64 percent in Grand County, about 100 miles northwest of Denver, said no. Many members of the state’s rural and agricultural communities felt that idealistic city slickers, who wouldn’t have to live with the consequences, had imposed an apex predator on them. Now the life-changing day had come, and locals hadn’t even been given a heads up.

“Nobody from the ag community was involved. No county official, no legislator knew what was going on until after the release,” says Ritschard, whose ranch is close to the release site. He only found out about the event from Facebook, after a friend spotted a caravan of CPW vehicles. The agency’s director, Jeff Davis, later apologized and vowed to improve communication ahead of future releases. A spokesperson for the agency also said that the event was kept small out of security and safety concerns. Ranchers still weren’t happy. “It started things off very rocky,” Ritschard says.

Two years later, Colorado’s wolf reintroduction—one of the most ambitious American conservation projects of the past century—has only gotten rockier. There have been almost 60 confirmed wolf depredations, or attacks, on livestock, though ranchers claim that number is actually much higher. The state has paid more than $610,000 to ranchers whose animals were killed or indirectly harmed by wolves; supporters call this compensation program the most generous in the nation, but ranchers say it doesn’t come close to covering their losses. Even those who haven’t experienced a depredation say they’re forced to spend more of their limited time and resources protecting their herds. Distrust and anger from the agriculture community is so intense that some ranchers won’t answer messages from CPW staff or allow the agency’s representatives on their land.

Wolves have become a flash point for Coloradans’ fears about big, existential issues: the urban-rural divide, the vanishing way of life that ranching symbolizes, and the question of what, precisely, humans owe to wildlife. “Wolves play an outsized role in our imagination, and this conflict is about what they represent,” says Matt Barnes, a conservation scientist who runs a rangeland management business based in southwest Colorado. “If your ancestors just spent the last hundred years making the West safe for sheep and cattle, reintroducing wolves is kind of a repudiation of your entire cultural history.” When the stakes are that high, is finding a middle ground even possible?

Less than a century ago, Coloradans were working assiduously not to restore wolves, but to exterminate them. The gray wolf once roamed more acres than any other mammal on Earth, with a North American population that some biologists think may have peaked around 2 million. In the 19th and 20th centuries, as Europeans moved into the West, losing livestock to wolves along the way, the federal government led a campaign to eradicate the species. Even the great naturalist President Theodore Roosevelt dismissed wolves as “beasts of waste and desolation.”

This was the era of manifest destiny, the widespread belief among white settlers that westward expansion, and man’s dominion over nature, was the will of God. The Bureau of Biological Survey, a precursor of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, hired hundreds of “wolfers”—expert hunters and trappers—in Colorado alone. These frontiersmen were not unlike wolves themselves: cunning, reclusive, feral. “Not too well acquainted with a bathtub, he rarely changed his clothes,” wrote one rancher of a trapper in San Miguel County. “Dirty, bearded, and unkempt, he lived mostly to kill wolves.” According to a 1918 report, at least 250 such hunters were deployed across the West that year. From 1915 to 1942, they killed more than 24,000 wolves in Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas.

Wolfers shot, trapped, clubbed, and poisoned their quarry. In Denver, the Bureau of Biological Survey opened the ominously named Eradication Methods Laboratory for the sole purpose of testing arsenic, cyanide, and strychnine to eliminate wolves and other predators, as Fort Lewis College history professor Andrew Gulliford writes in The Last Stand of the Pack: Critical Edition. Hunters left poison-laced carcasses out for wolves to eat. They also hid steel traps inside the bodies. Countless other creatures, such as eagles and bears, happened upon these lures and died too. Perhaps the cruelest method was “denning,” in which the hunter captured and chained a wolf pup near its den. Its plaintive cries would lure in the parents, at which point the hunter could easily shoot the whole family.

Hunters and park rangers celebrated the extermination of the last wolf pack in Yellowstone National Park in 1926. Eliminating wolves from Colorado would take at least another decade. The exact date is disputed, but by the mid-1940s, wolves were gone from the Centennial State—and, outside of a few patches of Michigan and Minnesota, the Lower 48.

In the aftermath of wolf eradication, American beliefs about nature shifted dramatically. The environmental movement emerged in the 1960s, and Congress passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973. The gray wolf was one of the first animals added to the federally endangered list. Two decades later, in 1995, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service took the first-of-its-kind step of reintroducing wolves to Yellowstone and Central Idaho. These transplants, as well as offspring from Canada’s naturally recovering population, gradually spread across the West. The species now occupies about 10 percent of its historical range in the contiguous United States.

As Yellowstone’s wolf population grew during the early aughts, scientists learned that the animals’ return had positive effects on the ecosystem. Wolves reduced overgrazing by preying on out-of-control elk populations. Native grasses and trees flourished, setting off a ripple effect, called a trophic cascade, that allowed other species, from birds to grizzlies, to thrive. It made for a compelling story: A 2014 YouTube video titled “How Wolves Change Rivers,” which depicts the creatures as a magic bullet for ecological restoration, has racked up 45 million views.

Its satisfying but simplistic message was complicated by a 2024 Colorado State University study that found the animals’ restorative effects, while real, had been overblown. By the late 2010s, however, the mythology was firmly in place—and lucrative. Wolf-watchers pumped an estimated $82.7 million into the Yellowstone region in 2021 alone.

Colorado environmentalists were emboldened by Yellowstone’s success. “The drumbeat for wolves in Colorado was already underway when paws hit the ground in Yellowstone, and then we had a real precedent for active restoration,” says Rob Edward, co-founder and president of the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project, which, along with other groups, spent three decades tabling at public events and publishing op-eds. Celebrity activists and groups, including media mogul Ted Turner’s foundation and Grateful Dead musician Bob Weir, donated and participated in ad campaigns.

Colorado wolf advocates initially asked the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to lead the state’s reintroduction effort, but the agency declined, in part because wolves were soon to be downgraded from nationally endangered to threatened status and because the Yellowstone initiative had cost an estimated $30 million and provoked intense pushback from local ranchers. Environmentalists then tried appealing to state lawmakers, but they weren’t interested, either: too costly and too controversial. Edward and fellow activists then had a radical idea. No state had ever tried bringing back an endangered species through a voter referendum, but polls showed that 60 to 70 percent of Coloradans supported wolf reintroduction. “So, we decided to take it to the people,” Edward says.

After wolf advocates gathered 211,000 signatures, nearly double the required number to get the measure on the statewide ballot—no easy task in 2020, when pandemic shutdowns made in-person canvassing difficult—groups on both sides of the issue spent considerable cash on ads to try to sway voters. The pro-wolf camp raised $2.4 million, and opponents brought in $1.06 million. Agricultural and hunting groups pushed back by raising legitimate concerns about the danger the predators posed to ranchers’ livestock. They also published scientifically dubious op-eds that claimed the animals could infect Coloradans with COVID-19 and fecal parasites.

The result was closer than that of any other statewide issue in 2020. Officials counted ballots for almost two full days after the election. It came down to just 57,000 votes: a 1.8 percent margin, with most urban and suburban residents voting yes and most rural Coloradans voting no. For the first time, a state was going to release an endangered species into the wild. “Unleash the hounds,” proclaimed the Colorado Sun.

Caitlyn Taussig’s recurring nightmares began not long after Wolf 2304 disappeared into the Grand County wilderness: harrowing dreams of walking through her herd, finding cows half-dead and ripped apart. “It’s really hard to keep the fear and anxiety down,” she says.

Taussig, 39, is a fourth-generation rancher. As a child, she bottle-fed newborn calves and warmed their trembling bodies with a hair dryer on frigid days. She loved riding on a sled that trailed her family’s horse team as it pulled feed through the snow to the herd. “It’s hard work, but it’s also the most wonderful childhood, because you’re out there with your animals,” Taussig says. She studied biology in college and considered a career as a wildlife biologist but ultimately felt that ranching was her calling. “As my mom likes to say, ‘Whenever I start feeling low, I just have to raise my eyes and look at the beauty of the land,’ ” Taussig says. “We feel connected to nature out here, and I can’t imagine working in a city or an office.”

Today, Taussig and her mother, Vicki, manage 3,000 acres near Kremmling, about 11 miles from where CPW staged its first release. When she’s not roping calves or fixing fences, Taussig is a singer-songwriter who has performed at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering. In “The Things We Gave Up,” she sings of the sacrifices that accompany a life working the land:

On January mornings, sometimes I feel old

When I’m bundled up pitching hay in the cold

But when calves come in spring, what nobody knows

Is there’s nothing I’d trade for this life that I chose

Like most ranchers, Taussig opposed wolf reintroduction. “The Front Range decided something that affects us,” she says. “I see comments on Facebook: ‘Why don’t you just fence your cows in?’ People really don’t understand how ranching works.”

Ranching was a tough business even before wolves came on the scene. “At busy times of the year, we work 70-, 80-hour weeks,” Taussig says. “And we don’t make much money.” She spends about three times as much on hay as she did 15 years ago, and drought can spike prices even more. Basic necessities—equipment, gas, fertilizer—ballooned due to inflation. The price of beef eventually caught up, but there was a lag time of a few years, she says—and during that lean period, she and her mother considered whether they could keep their business going. “We were really struggling,” she says, “and the question was coming up a lot: Do we still want to do this?” While Taussig hasn’t yet lost any livestock to a wolf attack, the time she spends on prevention—attending community meetings, installing game cameras and electric fences, checking her cows more often, even accompanying her dogs outside at night—has taken a toll.

A few miles away, fellow rancher Doug Bruchez, 40, shares the same concerns. “Since 2020, things have gotten much more difficult,” he says. “The price of beef has doubled, but our input costs have tripled.” A baler tractor he bought in 2013 for $110,000 would cost him nearly $300,000 today.

Bruchez is a fifth-generation rancher but doesn’t expect his kids to follow in his footsteps. Ranching is a tough way to make a living—and it’s a vanishing way of life. Only about three percent of Coloradans work in agriculture, and one in three producers in the state is 65 or older. Although Colorado ranks fifth in the nation for cattle sales and beef is our top agricultural export, the state’s total cattle inventory in early 2025 was roughly 2.5 million, down from 3.7 million in 1972.

Inside the barn on Bruchez’s 6,000-acre ranch, mounted elk and bighorn gaze down from the walls, as do plaques naming the many conservation awards his family has received: honors from the likes of Trout Unlimited and the Middle Park Conservation District. He’s collaborated with Colorado State University and Utah State University scientists on a study that analyzed water consumption in meadows. “We do this because we love wildlife,” he says. “There’s this narrative of the big, bad rancher…but we are stewards of the land.” He points out that a housing development abuts his property. By staying in business and not selling to developers, Bruchez argues, he and other ranchers help keep Colorado wild. And he doesn’t hate wolves: “I think they are amazing animals.” But he knows the dangers they pose better than most.

In April 2024, Bruchez became the first rancher in the state to experience a confirmed depredation by a wolf released by CPW. Finding the bloody carcass of a calf in the snow, he says, was a moment he will never forget. He kept a constant vigil after that. “I was sleeping in my car in the middle of the cows, getting about four hours a night,” Bruchez says. “Didn’t feel like myself; was grumpy with my wife and kids.”

His herd’s behavior changed too. “You used to be able to pet some of my cows,” he says. “Now if they see a human, horse, or dog, they start running.” After attending a Middle Park Stockgrowers meeting about wolves a month after the attack, Bruchez noticed his hands were trembling. His brother, a fireman, took his pulse and told him to go to the ER. “My blood pressure was 187 over 140,” he says—critically high. He started on blood pressure medication. Bruchez’s then-69-year-old father began helping out more and came down with similar symptoms. “He spent four days in the ICU,” Bruchez says, “and his diagnosis was congestive heart failure due to acute stress.”

CPW compensates ranchers for confirmed wolf kills and injuries, as do other states. Colorado goes a step further by paying for indirect losses, such as reduced pregnancy rates and weight loss among livestock following a depredation. Bruchez, for example, received $1,800 for the dead calf but got a total of $60,000 after his heifers and steers lost weight due to stress and his herd’s pregnancy rate dropped by five percent. (The vast majority of depredations involve cattle, but a few sheep, dogs, and at least one llama have been killed; CPW covers those too.) Conservationists point out that only a tiny fraction of the state’s cattle have been killed by wolves: fewer than 60 livestock so far in 2024 and 2025 combined, according to CPW data.

Ranchers counter that those affected are hit hard. Yes, they receive a hefty cash payout, but replacing a dead cow isn’t easy. Only a few breeds can thrive in Colorado’s mountain pastures, where altitude and severe winter weather make ranching harder than in most of the United States. Animals are bred over generations to be able to withstand these conditions; they can be difficult to source and cost more as a result. “But they use national averages to compensate us,” Bruchez says. “The cost of a cow in Kansas won’t buy me a cow here.” (CPW disputes this. The agency only uses national averages as a last resort when the rancher can’t produce a sales contract or receipt, spokesperson Luke Perkins says, and ranchers can challenge a valuation via an appeals process.)

In addition, confirming a wolf kill is tricky, especially when a carcass is never found or isn’t found until it’s in a late state of decay. Bruchez has had four other suspected depredations denied after CPW investigations. “Unless there’s an absolute smoking gun, they’re going to tell you it’s not a wolf,” he says. “And wolves eat the evidence.” Many ranchers believe the true number of kills far exceeds what the state is able to confirm. “You’re probably only seeing 10 percent of what’s actually happening,” Ritschard says. (Perkins says CPW has a two-tier compensation system that acknowledges that for every confirmed depredation there could be up to seven additional calves or sheep missing as a result of wolves.)

What’s beyond dispute is that ranchers deeply resent having to live with wolves—and seem to have directed most of their anger toward CPW. After we leave Bruchez’s barn, he and Ritschard, his friend and neighbor, take me on a tour of the ranch. It’s late summer haying season, and they want to drop off cold Coors Lights for Bruchez’s ranch hands, who have been cutting hay for hours. “What do you think of CPW’s handling of the wolf issue?” I ask two workers while they crack open cans. They laugh darkly and exchange a knowing glance. “You really don’t want to know,” says one, declining to give her name. “It’s nothing good.”

Thrown to the wolves, wolves at the door, a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The sheer number of idioms that reference the animals in a negative light shows how deeply ingrained our fear of them is. At the same time, the image of the wolf is one of the most recognizable, heroic symbols of American wilderness—its visage emblazoned on countless T-shirts and gift-shop knickknacks, its echoing howl set to stirring music in movies such as Dances With Wolves.

“Those polar-opposite views of wolves are really hard to reconcile,” says Barnes, the conservation scientist. He’s also on the board of the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project, and he served on the advisory group that helped CPW develop its reintroduction plan—a task that involved attending years of tense community meetings. That experience left him with an idea that might sound radical. “If we thought of this debate the way we think of religious conflicts in other parts of the world, we might come up with better ideas,” he says.

“In the Christian tradition, paradise is always depicted as a garden, never as the wild…. Do we manage nature like gardeners? That’s what many ranchers will say. Whereas if you talk to an environmentalist, they’re likely to argue for letting nature be wild and free.” Seen this way, Colorado’s wolf experiment is at its core a religious and cultural one, more than it is political or scientific.

Barnes’ argument is more than conjecture. Mireille Gonzalez, a social scientist who co-directs the Center for Human-Carnivore Coexistence at Colorado State University, spent six years studying the debate surrounding wolf reintroduction in Colorado. In a study published in 2024, she found that both pro- and anti-wolf Coloradans are driven by strong moral imperatives. Both groups believe they are being persecuted by the other, that they are victims of unfair and unjust actions. To find a solution, Gonzalez consulted the science of peace-building and conflict resolution. “Some of the scholars I follow most closely focus on the Israeli-Palestine conflict,” she says. What she discovered is that there’s no quick cure: To reconcile, you do the long, slow, tedious work of building trust.

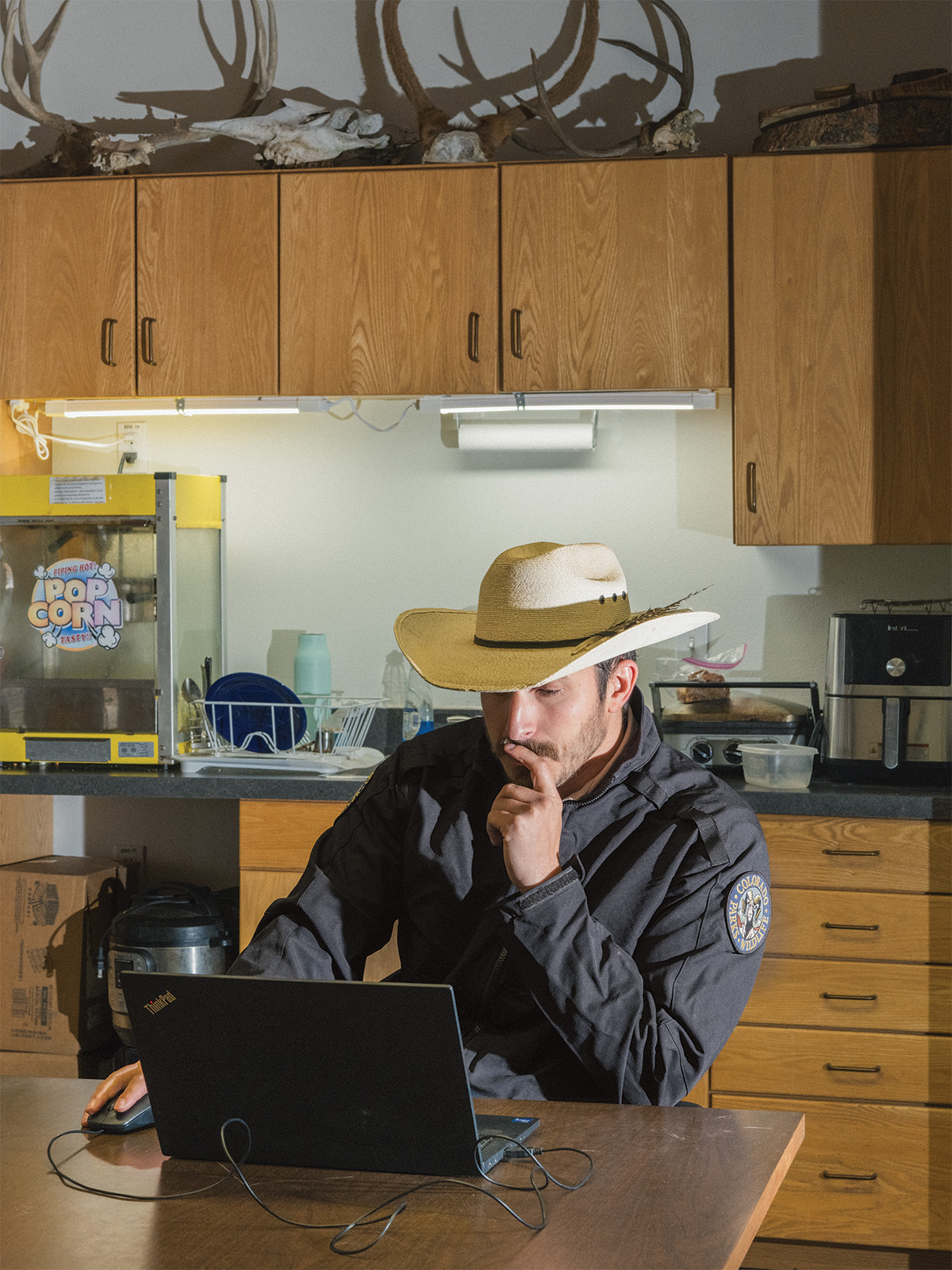

In Colorado, that job has largely fallen to Adam Baca. As the wolf conflict coordinator for CPW, Baca listens to cattle producers vent their frustrations, then offers practical solutions, like fladry (electric fencing with red flags that flap in the wind to deter wolves) and game cameras. He helps them apply for grants to defray the costs of these measures. Baca’s role falls somewhere between those of a therapist, a teacher, and a ranch hand.

It’s 5 a.m. and still pitch dark when I climb into Baca’s gray pickup in Walden, a far-flung community of fewer than 600 people about 20 miles south of the Wyoming border. The temperature on this late August morning hovers in the low 50s, but Baca is in his short-sleeve khaki CPW button-up and has the window down as we drive out of town. The New Mexico native recently spent five years working for the USDA, helping ranchers fend off wolves and bears in frigid Montana, so this weather seems mild to him. Baca speaks quietly and looks younger than his 31 years, despite his prodigious mustache and 10-gallon cowboy hat, which has three feathers—from a sage grouse, a turkey, and a mystery bird—tucked into the band. “You ready for a long day?” he asks, without taking his eyes off the road.

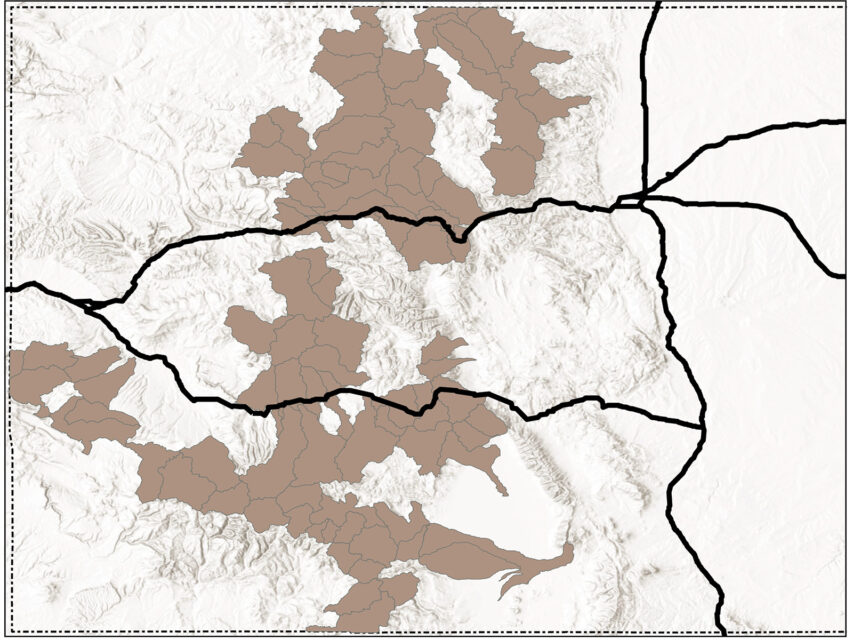

Baca lives in Walden but spends many of his days visiting rural properties across northern Colorado. There are currently fewer than 30 adult wolves across the state. CPW biologists use GPS collars to track wolves and map their movements, but it’s an imperfect science; the collars have a lag time of at least 16 hours, and not every animal wears one. Baca spends some of his time peering through night-vision binoculars at dots that may or may not be wolves. When he identifies one (either in person or via the GPS data), he texts nearby ranchers to warn them.

That’s what we’re doing now: keeping watch on ranchland in Jackson County as the first pink rays of dawn start to filter over the mountains. We sit quietly in the pickup while Baca scans the horizon, then hands the binocs to me. I see maybe 50 tiny black dots, unmoving and spaced several feet from one another: cattle at ease. This is a good sign, Baca explains. If a wolf were nearby, they’d be on the move and clustered for safety.

While serving as a lookout is tedious work, it’s actually one of Baca’s easier tasks. He often logs long hours—50- to 60-hour weeks aren’t uncommon, he says—in the field alongside producers, helping to install deterrents. “My job is to act as a bridge-builder,” Baca says. Building bridges is not easy in a climate where many ranchers are wary of CPW, if not outright hostile. The man whose land we’re on ignored his messages for more than a year. Baca won him over by continually showing up. “I’d see him around town and talk about anything but wolves,” he says. “ ‘How are your kids? How’s calving season going?’ You build trust slowly.”

Baca will put at least 130 miles on his truck over 12 hours today, visiting three ranches. Several of the landowners we met asked for anonymity, for reasons ranging from not wanting to anger friends who won’t collaborate with CPW to concern that wolf-watchers could locate their land and trespass to try to glimpse a wolf (a scenario that has already happened, according to the agency).

One of the hardest concepts for city people to grasp, a rancher in the North Park region tells me, is how strong his emotional connection is with his cattle. Yes, the animals end up on dinner plates—but before that, he cares for them around the clock. “It’s not just a cow,” he says. “They are like a family member.… We calve them, we doctor them, feed them, watch the moms raise their babies. And then a wolf comes in and desecrates it.”

He was wary of Baca at first. Even before the wolf reintroduction, the relationship between government and ranchers was tense. To wit: Polis raised ranchers’ ire when he declared March 20, 2021, “MeatOut Day” in the state. The ceremonial proclamation was meant to encourage Coloradans to eat more plant-based foods, not to give up meat entirely, but cattle producers saw it as a tone-deaf attack. “Sometimes I think the state is trying to get rid of agriculture,” the North Park rancher says.

But he thought wolves were getting into his herd—“you could tell the cows were disturbed, edgy,” he says—so he agreed to install fladry and flashing lights, called foxlights, with Baca’s help. Like all deterrents, fladry helps only in certain situations—for example, it’s impractical across large areas. In this case, though, it worked. “Once we put up the flags and the foxlights, the wolves didn’t really come,” the rancher says. Happy endings like these, Baca says, are much more common than most media coverage of Colorado wolves would lead you to believe. While the state meticulously tracks—and reporters dutifully cover—each depredation, no one can know how many times a wolf turned tail, nor does that outcome make for a thrilling headline.

People are not allowed to hunt, shoot, or have direct contact with wolves, which are still endangered. (Ranchers may kill a wolf if they catch it attacking their livestock, though that hasn’t happened yet.) In addition to fladry and foxlights, ranchers can employ nonlethal bullets that flash and pop; dogs trained to guard the herd; and scare devices that emit noise. CPW is also studying the potential of drones; the USDA used them in Oregon, where they blasted an audio clip of Adam Driver’s and Scarlett Johansson’s characters arguing in the movie A Marriage Story. Something about the scene, apparently, repels wolves. CPW has also hired nine damage specialists who inspect each suspected wolf kill and, similarly to Baca, work proactively with ranchers to try to prevent attacks.

Everyone believes range riding—old-fashioned cowboying, in which a mounted rider patrols the herd—is one of the most effective tools. In May, CPW announced it had hired 11 range riders, in addition to two who work for the Colorado Department of Agriculture; some ranchers also hire their own riders. The riders use horses, ATVs, and night-vision technology; they sometimes launch nonlethal pepper balls or leave out clothing that carries a human’s scent.

Other ranchers are trying out private-sector solutions. Adam VanValkenburg, who works 2,300 acres in Jackson County, is testing new game camera software developed by the Fraser-based nonprofit Wild Ranch. The software uses artificial intelligence to determine which predator (wolf, bear, coyote, mountain lion) is approaching and then plays the noise best suited to scaring that particular species. “I opposed wolves,” VanValkenburg says. “Dealing with them is a full-time job. But my motto is, you’ve got to deal with what you’ve been dealt.”

All these conflict-minimization techniques don’t come cheap, which speaks to the fine line CPW must walk: Ranchers are asking for more help, and the agency has stepped up to provide it, but increased spending leads to more criticism. During the 2025 special legislative session, state Senator Dylan Roberts, who represents the northwest corner of Colorado (including Taussig’s and Bruchez’s ranches), sponsored a bill to cut wolf funding and pause releases. Lawmakers stripped the hiatus from the bill as a compromise to get it passed, but the funding cut, which redirected $264,268 to health insurance subsidies, became law. “Voters were promised that the wolf program was going to cost $800,000 a year, but this past fiscal year, it cost taxpayers $3.5 million,” Roberts told the Colorado Sun. (CPW disputes this; Eric Odell, wolf conservation program manager, says the $800,000 estimate was never intended to be comprehensive and did not include depredation payments, among other line items.)

Determining what’s fair to everyone—to ranchers, to taxpayers, to wolves—is a Sisyphean task for the state. “It’s very hard,” Odell says. “There’s a lot to balance.” When the agency decides to kill a problem wolf that repeatedly attacks livestock, a step it’s now taken twice, environmentalist groups protest. “CPW is in a very tough spot,” says another rancher who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “They’re trying to do the right thing, but they’re getting it from both sides.”

If everything goes to plan, Colorado’s next round of releases will happen some time this winter, part of a five-year goal for about 30 to 50 wolves to be transferred here from other states. Once the population, currently estimated at fewer than 30 adults, reaches 50 for four years, the animals will be downlisted from state endangered to state threatened. To be delisted entirely, the population will need to hit 150 wolves for two years, or 200 with no time constraint. That milestone is significant in part because it could someday mean that wolf hunting (with strict limits) might become legal here, as it has in four other states. While most ranchers don’t look forward to a population that large, many believe legal hunting will make wolves more fearful of humans and cattle, decreasing depredations.

Odell, CPW’s wolf program manager, acknowledges that the agency has made missteps, especially in communication and outreach in the first year, but says he’s excited for the future. Four wolf packs—based in Jackson, Pitkin, Rio Blanco, and Routt counties—now roam the state, and in June the agency released game camera footage of pups in Routt County playfully tumbling and licking one another. “We don’t have a self-sustaining population yet, but it feels like we’re on the way, like we’re nearing a tipping point,” Odell says. “We’ve been very successful on the biology side of things. There are things we would do differently…. But we are trying to regain trust, trying to be as transparent as possible.”

Meanwhile, scientists are gleefully gathering data from one of the most ambitious experiments in wildlife conservation history. This past summer, I met with CPW wolf monitoring and data coordinator Brenna Cassidy in her small basement office at the agency’s headquarters in Fort Collins. GPS collars were neatly stacked on a shelf across from her desk, and boxes of syringes and empty tranquilizer darts sat on a table.

Every day, Cassidy meticulously tracks the animals’ movements on her computer. She pulled up an image that looked to me like random scribbling, but it caused her eyes to light up. It was the movement of Wolf 2516, a lone female that has traveled thousands of miles, a highly unusual behavior. “She’s seen most of the western half of Colorado,” Cassidy said. She has no idea why. “It’s incredible, the distance she’s moving.” She added that wolf social dynamics are highly complex and the stereotype of the “alpha male” is false—one of many myths researchers have debunked in recent years. “Some of the things we’re just now learning are fascinating,” Cassidy said. “Even though wolves are one of the most studied mammals on the planet, there’s a lot we still don’t know. ”

Ranchers, again, choose different words. Several I spoke with were dismissive of wolf deterrence strategies, listing their limitations and drawbacks and generally bristling at the idea of nonranchers telling them how to do their jobs. Bruchez met with Baca but wasn’t impressed. “He shows up with a three-ring binder of check-the-box paperwork…but this isn’t a one-size-fits-all scenario,” Bruchez says. Electric fences can be impractical to install and maintain, he says, and they come with risks. “CPW assumes no liability. If my neighbor’s horse gets tangled up in fladry and dies, I’m buying my neighbor a new horse.” (Perkins concedes that generally speaking, CPW would not be at fault but also says there have been no reported instances of livestock experiencing injuries related to fladry.)

In September 2024, CPW captured the pack near Bruchez’s ranch after a series of confirmed depredations and relocated it to Pitkin County, so his family’s stress has abated. But he wonders when the predators will return and how life will change as their numbers increase.

Perhaps the best glimpse of Colorado’s future may come from those who have lived alongside the animals longer. Wolves have stalked the land near Denny Iverson’s ranch in Missoula, Montana, for 15 years. He has had one confirmed wolf depredation and suspects the true number is higher. The wolves’ arrival was a struggle, but he adjusted, using range riding to some success. In his role as a board member of the Blackfoot Challenge, a Montana-based nonprofit whose mission includes helping ranchers cope with carnivores, he’s made several visits to Colorado ranchers. “I tell them it’s not much fun right now, but it’ll get better,” Iverson says. “It’s going to be OK.” Colorado’s compensation program is “robust, better than Montana’s,” he says, and hunting should “put some fear into” the predators if it’s legalized.

Still, wolves are here to stay. “Some ranchers will accept reality and learn to live with them,” Iverson says, “and some will stay grumpy for the rest of their lives.”

Read More: