The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

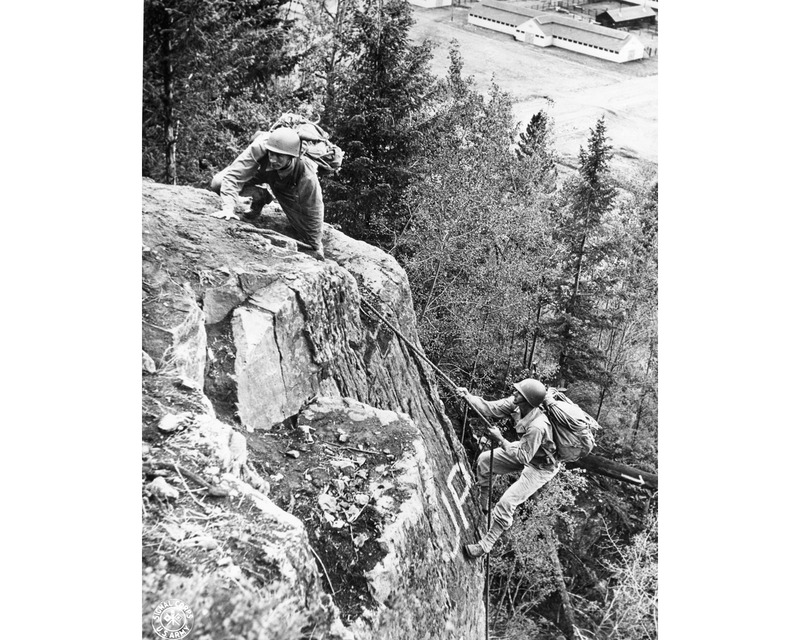

When Ski Cooper opens in December, powder hounds making turns at 10,000 feet will be shredding hallowed ground, and not just because Cooper is one of Colorado’s oldest ski resorts. From 1942 to 1945, more than 14,000 soldiers perfected skiing, climbing, mountaineering, and fighting techniques here at Camp Hale, the Army’s brutal training ground for the newly formed 10th Mountain Division. In 1945, the 10th Mountain soldiers would pull off an astounding feat in Italy: breaking through the German lines on Riva Ridge and Mount Belvedere to provide access to northern Italy. It was an important win for the Allies, but a bloody fight. A memorial at the entrance to Ski Cooper carries the names of the 992 men who did not come home.

This winter, U.S. Senator Michael Bennet hopes to introduce legislation that will remember the 10th Mountain Division with more than stone and bronze: He aims to establish Camp Hale as the nation’s first National Historic Landscape.

Although specific guidelines have not yet been worked out, the National Historic Landscape designation would be a hybrid that would put equal emphasis on preserving outdoor recreation and providing education about the 10th Mountain Division’s legacy. It would ensure that roughly 30,000 acres around Camp Hale remain open to activities like hiking, climbing, skiing, fishing, and even snowmobiling—a modern-day echo of how soldiers used the land. (The 10th Mountain Division’s “weasel” was a precursor to today’s snowmobile.) “[The designation] was the suggestion of veterans in Colorado, actually,” Bennet says. “I can’t think of a place that’s more appropriate, because of the history and what they achieved.”

The Camp Hale designation would be but a small piece of a much larger public lands package that would likely resemble U.S. Representative Jared Polis’ 2015 Continental Divide Wilderness Bill, which at press time was awaiting a hearing in the House Committee on Natural Resources. Polis’ legislation calls for the protection of 40,000 acres in Summit and Eagle counties as wilderness, the highest level of protection for public lands. Practically, that means prioritizing habitat preservation and human-powered recreation over development and mechanized pursuits. Polis’ bill also seeks to classify 5,204 acres of habitat north of Keystone as the Porcupine Gulch Protection Area to preserve wildlife habitat near one of the few land bridges across I-70. And in the Tenmile Range near Breckenridge—already a popular mountain biking area—11,417 acres would be devoted to recreational access.

Spearheaded in part by Conservation Colorado, the legislation’s supporters run the gamut from Vail Resorts to Colorado Springs Utilities, which is keenly interested in preserving the quality of the water that flows into its reservoirs from the Upper Blue River. While public lands bills haven’t fared particularly well in recent years, the collaborative is optimistic about the bill’s chances, given its broad base of support. “Every year we lose more 10th Mountain Division veterans,” says Garett Reppenhagen, an Iraq Army veteran and the Rocky Mountain West coordinator for Vet Voice Foundation, one of the bill’s biggest champions. “It’d be great to get this done before we lose any more. I’d like as many as possible to be able to come to this area, to stand in this place where they trained, knowing that the ground beneath them is protected federally.”