The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Since school began at the University of Colorado Boulder in August, it’s been one piece of bad news after another.

Almost immediately, the university community saw a significant rise in coronavirus cases, many of which were traced to off-campus parties and a failure to wear masks or social distance. As of October 2, the college’s on-campus testing portal reported 1,082 positive cases of COVID-19—the Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment reported 1,503 confirmed cases—making the university the state’s single largest outbreak since the pandemic began.

In an attempt to quell the spread, CU and the City of Boulder have taken some extraordinary measures—from imposing mandatory quarantine orders on off-campus fraternities, sororities, and other student housing to shifting completely to online learning. Then, on September 24, Boulder County Public Health went a step further, issuing a 14-day public health order that prohibits gatherings of more than two individuals aged 18–22 and placing 36 off-campus properties under a stay-at-home order. Failure to comply with the order could result in a fine up to $5,000 and up to 18 months in jail.

CU is not the only U.S. college to see a significant rise in coronavirus cases. Schools across the country, like the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Notre Dame, have faced similar challenges, and have elected to move to temporary virtual instruction in an effort to control the virus.

But just north of Boulder, Colorado State University is having a much different experience. Despite the fact that CU and CSU have similar enrollment numbers—CU at almost 35,000 students this semester, and CSU at more than 34,000 students as of the 2019–20 school year—CSU hasn’t seen the same rapid spread of COVID-19. As of October 4, the university reported 436 cases through its on-campus portal. And as of October 1, the positivity rate for CSU was four times lower than that at CU.

The schools’ approaches to managing the virus are similar in some ways. For example, both are implementing local public health measures, promoting socially distanced learning in the classroom, expansive testing, contact tracing, using daily symptom checkers, and looking for potential outbreaks through the examination of wastewater on campus. On September 25, CSU announced that wastewater at two residence halls—Braiden and Summit—tested positive for COVID-19, and imposed mandatory quarantines and testing for students in those dorms. Nine students total tested positive for the virus and remained in quarantine, while the rest of the students were able to return to their usual schedules.

The differences between the universities are a bit harder to nail down. While CU Boulder requires testing for all community members once weekly, CSU only mandates testing for targeted populations, like those who are living in close quarters—students in residence halls or sororities and fraternities—staff and faculty who are in close contact with students, or areas flagged by wastewater examination, says Lori Lynn, executive director of CSU’s Health Network and co-chair of the school’s pandemic preparedness team.

Although CU is doing more weekly testing, that isn’t necessarily why they’re seeing more positive cases, says Chana Goussetis, a public information officer with Boulder County Public Health (BCPH). “It wouldn’t be the case because we’re looking at the percent of positivity, so that removes the question of ‘well there’s more tests, so there’s more positives,’” she says. “But if you look at the percent, the percent has gone up, so that says to us there actually has been an increase regardless of more testing or not.”

Still, Melanie Marquez Parra, director of communications and chief spokesperson for CU, said in an email to 5280 after this article published that comparing the percent positive of CU Boulder to other testing programs is not reliable. CU has initiated weekly, saliva-based PCR testing for all individuals residing in residence halls, as well as offers additional testing to symptomatic individuals or those who were in contact who someone who tested positive for COVID-19. Any positive results from the saliva-based tests are then confirmed through PCR testing.

CSU is taking a multi-pronged approach to preventing the virus’s spread, says CSU Provost Mary Pedersen. “Not only are we really focusing on strategic testing, we’ve also had a very strong social norming campaign, where we’re using peer influence to follow our public health guidelines, and that includes using face coverings everywhere; it includes hand sanitation stations before going into every classroom; it includes the students maintaining a minimum six-foot social distancing in a classroom environment; the students go in with sanitary wipes and wipe down the desks that they’re going to be sitting at—all of those are really important things,” says Pedersen. “It is the testing, public health safety measures, and a social-norming campaign. We’ve been trying to hit it from as many angles as we can think of.”

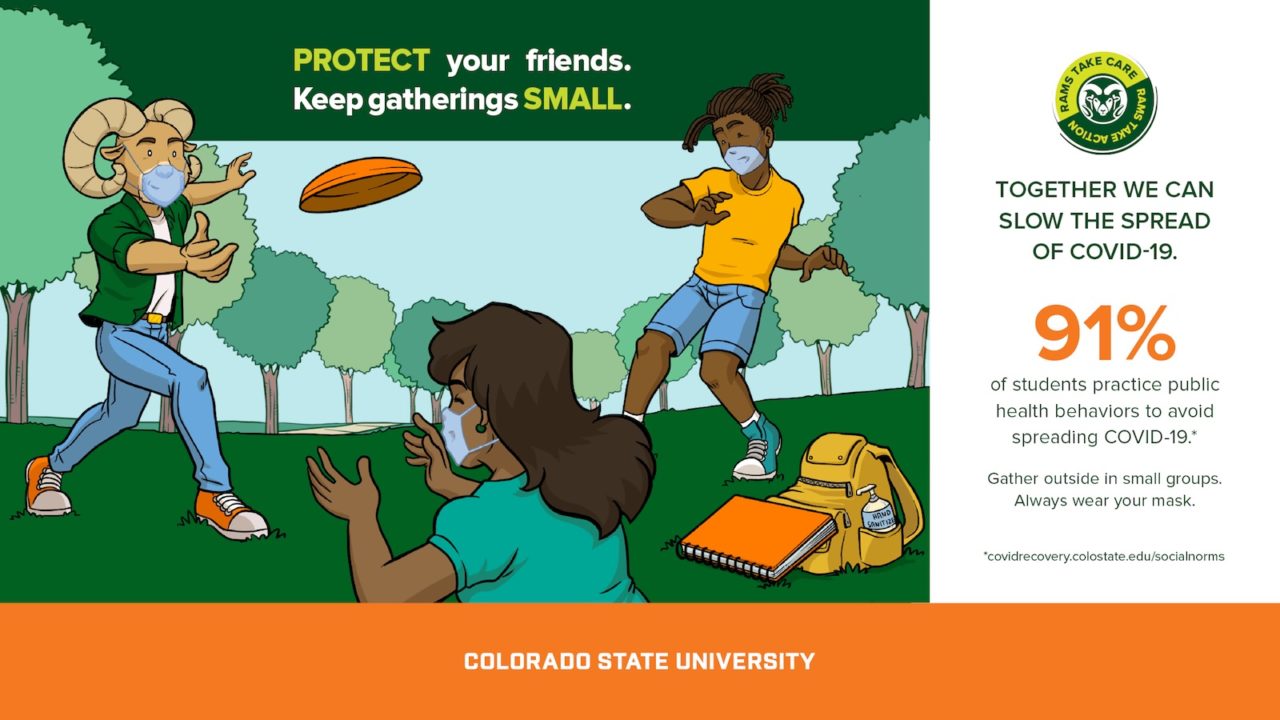

CSU’s social norms campaign is led by a social norming task force made up of students, faculty, and staff. The program encourages peers to follow health guidelines with messaging like: “My face covering protects you, your face covering protects me;” “Protect your friends, keep gatherings small;” and “Together we can slow the spread of COVID-19.” In a survey by the task force to understand students’ feelings toward the health guidelines, 91 percent of respondents said they practice public health behaviors to avoid spreading COVID-19.

Lynn says that contact tracing at CSU has revealed that positive cases in the community are coming from small social gatherings, rather than large parties that are being reported at CU. That assertion is backed up by Katie O’Donnell, public information officer for Larimer County Department of Health and Environment (LCDHE). “Our students haven’t been partying. They’ve taken the requirements really seriously,” says O’Donnell. “When they first came back to campus in early August—that’s our move-in for our off-campus housing—we were getting complaints about these college-aged large gatherings, and that has almost completely ceased. We oversee the complaints and the compliance here in the county, and they’re almost nonexistent.”

Lynn says that CSU uses the social-norming campaign to educate and counsel students who have been reported for any health violations, but they will send them to Student Conduct if needed. Intervention at CSU began early on—a decision based on other schools across the country that started earlier and saw lots of partying, O’Donnell says. While CSU did receive complaints from the Fort Collins community early on, letters went out to students about their expectations before any cases were tied to those incidents.

Goussetis, with BCPH, says that CU has recently gotten tougher with holding students accountable for not following guidelines. As of Sept. 30, 260 students at CU have required educational intervention, as is reported on the school’s COVID-19 response dashboards. Of these, 28 students are experiencing interim exclusions, where students are not allowed on campus while awaiting judgement from their conduct hearing; 40 have been placed on probation, which can affect students’ ability to work some on-campus jobs, study abroad, or get into graduate school; and 13 are on interim suspension, where students are not allowed to attend classes while awaiting judgement from their conduct hearing. Three students have been suspended. (CSU declined to provide detailed information on how many students have been referred for educational interventions.)

Both schools have been working closely with their counties’ public health departments to track cases and prevent further spread within the community, and the universities are sharing information on what is and isn’t working with each other along the way, according to Parra. O’Donnell says that representatives from LCDHE are included on CSU’s pandemic preparedness team—and they talk constantly. The school’s contact-tracing system is also built into the county’s platform, which has been a driving force in keeping the community’s cases down as a whole—a model that’s been successful and that is also used for other schools in the county, she says.

“It’s less of a ‘we tell them when they’re doing something wrong,’ and much more of a collaboration, and it has been that way since really early on in this response,” O’Donnell says. “We’re working off the same platform with the same guidelines with the same restrictions, so [schools] are not getting two different sides of public health, they’re getting one voice.”

CSU also has a rapid response team that meets every night to discuss their next moves, and LCDHE gets briefed on their meeting. In addition to public health experts, the college is tapping into its own experts to make sure the school is taking a robust approach. Researchers across 12 disciplines are chiming in on everything from monitoring wastewater to developing a rapid saliva-based test.

“I think what is so amazing to me… is the breadth of expertise all coming together,” Pedersen says. “Every day we’re just trying to learn and figure out how to deal with it. There’s no guidebook.”

Editor’s note, 10/13/20: This article has been updated with new information supplied by CU representatives after publication.