The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

You may be aware that the planet has been experiencing a La Niña weather pattern for the past two years. That has meant differing things for Colorado: The 2020-’21 winter produced above average snow for the Denver area—primarily due to a spring blizzard—but many mountain locations ended their seasons with snow totals below, or well below, average. Likewise, this past winter produced below average snow totals for numerous mountain locations, most notably the San Juans.

La Niña conditions typically persist for nine to 12 months, but they can last longer. And, indeed, climatologists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder are predicting that the current La Niña weather pattern will continue into for a third year for only the third time since 1950, when researchers started keeping official records on La Niña and El Niño. Here’s what that could mean for Colorado.

First things first: What is La Niña (and El Niño)?

The La Niña weather pattern is just one part of what’s known among climatologists as El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). ENSO has three phases: Neutral is the default phase, in which temperatures in the equatorial waters of the Pacific Ocean are near normal. El Niño, “little boy” in Spanish, means there are warmer waters in the equatorial Pacific, and La Niña, or “little girl” in Spanish, means cooler waters in the equatorial Pacific.

How could cooler water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean affect weather in Colorado?

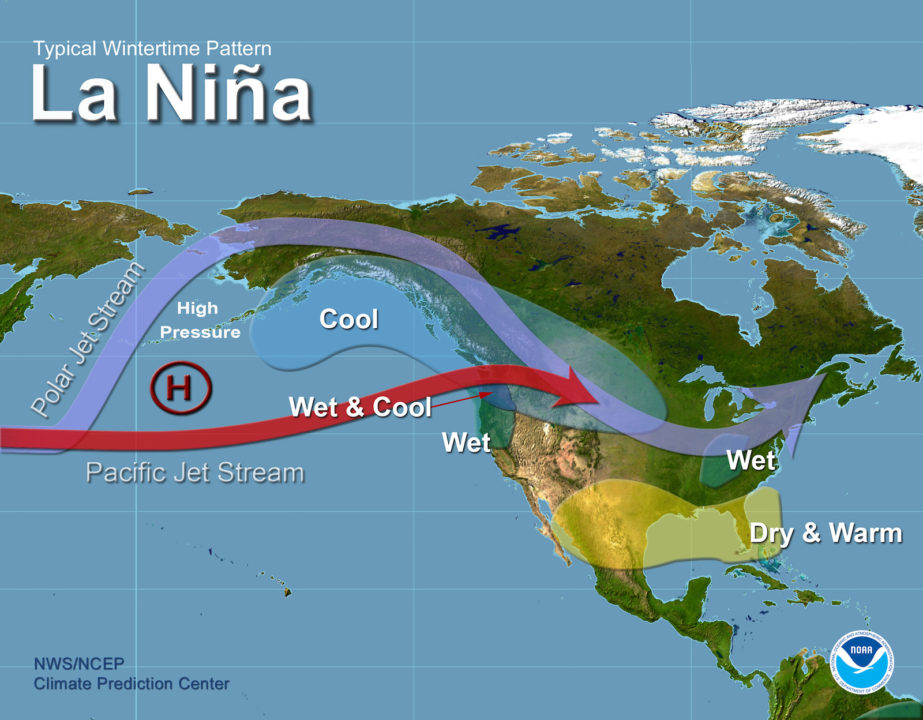

The cooler waters off the western coasts of the Americas affect global weather patterns. You will often hear about how La Niña can heighten the hurricane season in the Atlantic basin. La Niña also bends the jet stream to the north in the Northern Hemisphere during the winter. This creates wet weather in the Pacific Northwest and drier weather in the southwestern part of the United States.

Deepening drought conditions, wildfires, and more severe weather in general are typical impacts one might see in the southwestern United States during a La Niña weather pattern. For Colorado and the surrounding region, that’s never great news—but it’s especially bad when the phenomenon lasts as long as it already has. One can easily imagine the impacts a dry and hot summer could have on the region—larger wildfires and water rationing, for starters—only to be followed by a warm, dry winter.

Why is this particular La Niña such a big deal?

Since 1950, when official record-keeping for ENSO began, there have only been two instances where a La Niña persisted for three winters in a row. The first started in the spring of 1973 and ended in the spring of 1976. The other began in the summer of 1998 and lasted till spring 2001.

This would be only the third time since Harry Truman was president where a La Niña lasted three winters in a row. This past spring, water temperatures in the Pacific not only continued to run below normal, but in fact appeared to be decreasing. La Niña doesn’t typically strengthen in the spring, leading climatologists to believe we are headed for a rare so-called “triple dip,” or a third fall and winter of La Niña conditions.

The biggest concern for those of us in Colorado would be the lack of snow this coming winter, exacerbating already distressing drought conditions in the Centennial State and the southwestern U.S. The last winters of the only two “triple-dip” La Niñas produced much less snow than normal for mountain locations. The winter of 1976-’77 left most mountain locations with a four- to seven-foot deficit by the end of the season. The winter of 2001-’02 left most mountain locations with a two- to four-foot deficit.

Are there any benefits to the continued La Niña conditions?

There are: The cool waters of the Pacific tend to keep global temperatures down. That’s a good thing. As for Colorado weather, as we all know, it’s unpredictable. As we prepare for what may be a quiet winter based on forecasts, Coloradans will need to hope for a strong monsoon season—and perhaps even make a special request to Ullr, a Norse god associated with skiing and cold-weather sports, for a snowy 2022-’23 winter.