The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

If you hit one cultural event north of Denver this year, the Boulder International Film Fest is a can’t-miss cinematic celebration to get your fill of provocative deep dives, artistic excellence, and exhilarating adventures on the big screen.

Sixty filmmakers will appear at the festival, including 20 from Colorado, and attendees can catch three world premieres and half a dozen U.S. premieres. From local environmentalists and barrier-breaking pioneers to one of the world’s most prolific fashion icons, the subjects and themes of this year’s 68 film selections are a testament to cinematic diversity and poignant storytelling.

How To Check Out the Boulder International Film Festival

- Where: Films screen at a variety of venues in Boulder (including the Boulder Theater, Cinemark Century Boulder, and other downtown spots) and the Stewart Auditorium in Longmont. Check out the Film Guide to put your weekend schedule together, and get your passes ($195–$495) and ticket packs ($35–$105) ahead of time.

- Things to do: Don’t forget extras like tonight’s beloved CineCHEF culinary extravaganza, the Opening Night Red Carpet Gala on Friday, March 14, the Adventure Film Program and party, the BIFF Singer/Songwriter Showcase and Teen Short Film Competition, and a bevy of Q&As and talkbacks with film subjects and filmmakers.

- How to stream: Can’t make it this weekend? Worry not—you can stream some films at home starting March 17 through BIFF’s Virtual Cinema.

4 Can’t-Miss Films at BIFF 2025

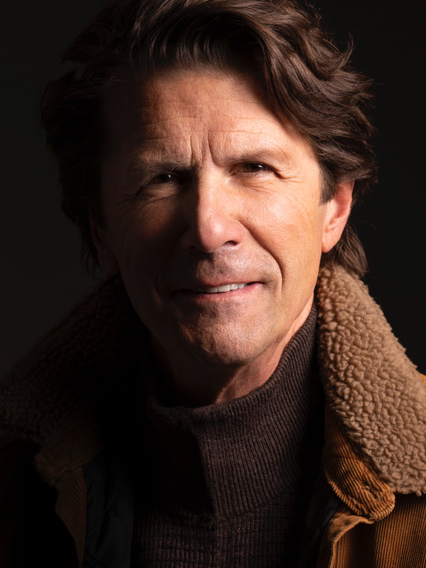

Below, four flicks worth watching this weekend, plus a conversation with Colorado’s own James Balog, the subject of Chasing Time, who spent 15 years photographing retreating glaciers to compile one of history’s most compelling and visually stunning bodies of evidence depicting climate change in real time.

1. Champions of the Golden Valley (81 mins.)

- Line that stuck with us: “For me, skiing is not a sport. It’s just a school to learn living. To work hard. To be patient. To be strong. To don’t [sic] give up.”

In our part of the world, we’re used to in-your-face ski films made with slick drone footage of death-defying and limit-pushing stunts in a sport we call our own. This film is not that—it’s better.

Champions of the Golden Valley is the story of skiing and humanity in the harsh and forgotten mountain villages of Bamyan, Afghanistan. It’s the story of athletes who persevere to learn a sport they love by building makeshift wooden skis and rigging a motorbike-powered towrope up a mountainside. Cameras capture the rivalry, camaraderie, training, and utter joy of the athletes, children, and a coach as they prepare for the annual Afghan Ski Challenge.

The twist: Filming began before the collapse of their country with the Taliban takeover in 2021, which decimated the fledgling ski community and scattered many—especially women—who’d appeared on screen in the early ski footage, forced to flee their homes to avoid persecution. The film’s lynchpin, Coach Alishah Farhang, sought assistance to flee with his family, and viewers get a peek at his refugee life in Germany as he reflects the ways that skiing brought light and love and self-worth to his people before it was so cruelly ripped away. Anyone who’s ever skied a run down a hill and felt the wind on their face will be glued to the screen.

2. A Man with Sole: The Impact of Kenneth Cole (98 mins.)

- Line that stuck with us: “Kenneth wasn’t worried about, ‘If I speak up, will this affect my business?’ He was worried about, ‘If I didn’t speak up, is the business worth it?’ ”

Maybe we’ve been living under a rock, but we were unaware that Kenneth Cole—a name synonymous with slingbacks and day-to-night blazers in our orbit—was such a powerhouse social activist. Which is why this retrospective of Cole’s evolution as a businessman and a champion of generation-defining social causes—dismantling the AIDS stigma, ending gun violence, and destigmatizing mental health problems, chief among them—was so eye-opening.

Over the course of a timeline that launches with Cole’s tenacious debut selling shoes out of the back of a truck parked in front of the New York Shoe Expo, A Man with Sole explores Cole’s journey as a determined, visionary, often controversial, always principles-driven consumer fashion icon who uses his global platform to advocate and disrupt in the name of tackling some of society’s biggest social challenges.

3. Spacewoman (90 mins.)

- Line that stuck with us: “But I didn’t tell anybody I wanted to be a pilot, or that I wanted to be an astronaut, because I knew they were going to say, ‘You can’t do that—you’re a girl.’ ”

A perfect pick to pay homage to Women’s History Month, this honest and revealing portrait of Eileen Collins, the first woman in history to pilot and command the U.S. Space Shuttle, is a must-see for anyone curious about the ins and outs of smashing a glass ceiling and stepping over the shards like they’re not even there.

In Spacewoman, Collins, who will be on hand at the festival for a post-screening conversation on closing night, shares her life candidly on screen—from her hardship-laden, working-class upbringing to her rise against all odds through military and NASA ranks to her complicated relationship with her daughter as she balanced an unfathomably risky career and her unquenchable thirst to conquer space with love for her family. Footage from early in Collins’ career, extensive interviews with her colleagues and champions, and an introspective exploration of personal motivations and memories by Collins herself weave the fascinating life story of a fearless first-in-history female space commander who held the future of the U.S. Space Program on her shoulders—and never once dropped it.

4. Chasing Time (39 mins.)

- Line that stuck with us: “The ice will be a representation to the people 100 years from now of how badly this civilization failed.”

A dozen years ago, we interviewed renowned Boulder environmental photographer James Balog, the intrepid explorer behind the groundbreaking Extreme Ice Survey (EIS), when the Emmy Award–winning film Chasing Ice premiered. Balog’s first-of-its-kind EIS documents glacial retreat via long-term time-lapse photography in some of the most remote corners of the planet. Little did we know that today, Balog would be chatting with us again about the culmination of EIS and his journey to wrap up one of the most extraordinary climate change projects in history, all folded into a thoughtful documentary, Chasing Time (a sequel, of sorts, to Chasing Ice).

Helmed by longtime colleague, mentee, and director Jeff Orlowski-Yang, with Sarah Keo, Chasing Time follows Balog and his team of adventurers on a bittersweet expedition to remove the last camera from its remote post. Balog and his team reflect on the past and ponder the future, confronting the ideas of mortality and legacy as they relate to themselves and our increasingly fragile—as captured for eternity in Balog’s images—planet.

We recently caught up with Balog for a quick discussion about his work and the new film.

Editor’s note: The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

5280: When EIS first launched, did you have any grasp on how long it would run?

James Balog: The timelapse cameras went out in 2007. I thought it was a three-year project. Three summers, two winters. Once we got there, it was like, “Holy smokes, we can’t stop now—we’re getting this incredible evidence! Let’s go to five years.” We got there, and it was, “Wow, we’ve got a big historical record—let’s keep going.” Every time we came to some chronological landmark, it just kept going.

Eventually, I just became exhausted from raising the money to keep the system alive, and from taking the risk of sending myself and my team members out into these dangerous locations. And, I just felt like, Boy, let’s thank our lucky stars nobody’s been hurt or killed all this time. It’s time to stop. And, we’ve told the story. We’ve got the proof.

The film touches on the value of your mentorship in Jeff’s life and work. How do you view your role as a mentor?

I certainly want to keep inspiring younger creative people in whatever medium they’re in to keep swinging for the fences, doing everything they can with the circumstances they’re dealing with to tell the stories that matter. I hope that if it’s just one person in the United States and one person in Europe and one person in Africa who sees this and is inspired in their own work, that will be reason enough for having done this film.

What kind of message do you hope your work leaves for generations down the road?

That’s a really big thing in my mind: What we’re leaving behind for the unknown people in the future. I feel a strong sense of responsibility to be able to say to those people in the future, “Look, some of us were paying attention.”

Do you think people today are paying attention?

I believe that the majority of Americans understand there’s a problem of the changing climate that is leading to these extreme [wildfire, hurricane, flood] events. But we have this very vocal, hardcore, right-wing denialist system, and they’ve been very effective in combining a belief that’s contrary to the physical evidence with an ideological, cultural dogma they’ve been selling. I believe the people of the future would be sickened by the realization of how mule-headed too many people were in the face of the evidence that was all around us.

The film dips into your personal struggle with multiple myeloma. How did that journey affect your work?

It’s been an interesting process to feel the urgency of taking care of my individual organism at the same time I feel the increased urgency of taking care of our collective organism. When you get a diagnosis like that, it really sharpens your sense of mortality. Simultaneously, I’ve had this very rapid increase in my sense of the mortality of the climate and the environment in general. Those two things have gone hand in hand. I really want to say that the urgency of taking care of the natural environment has never been greater than it is right now.

The remote style of photography you do seems to be hugely solo, yet hinges on collective passion. How do you reconcile those?

It’s both a team thing and my life’s work. Somebody has to lead the caravan, and it’s my intensity that does it, and my passion and my need to express something that does it. At the same time, I’ve been incredibly grateful for the broad range of friends and allies who’ve worked on this. And, certainly, for the love and support of the core team. They’ve made an incredible difference in the execution of the work. And it goes way beyond them. The work stands on the shoulders of all of us. I’m very conscious as I’ve gotten older that a creative person is not a solo maverick.

How does your work translate into tangible human-driven change?

That question transcends any film, work of art, book, TV show, whatever. We’re talking about enormous historical times here that my film and work is a small part of. It happens to be a pretty large part of what has come out of the creative community, but in terms of the broader, global historical context, it’s still small. That context means 150 years of burning fossil fuels, power and transportation generation, the momentum of the natural system outside humanity, political and financial systems, how money is allocated, how power moves along with the money…. All these things matter. Through the arts, we can put our finger on the scale a little bit—but we’re not going to singlehandedly move the scales.

How do you explain climate change to those that say it’s not real?

People have really had a hard time with separating out the difference between a belief system and tangible facts. Belief systems are useful in a lot of ways in this world, especially in trying to deal with the great existential questions: Where did we come from? Where are we going after we die? Why are we on living on this stone swirling around the Milky Way? They also give us an excellent ethical, moral foundation if we choose to follow them. But, they have nothing to do with the tangible facts of the measurable, observable world. That’s what is so mind-boggling to me: that there are so many people willing to ignore the evidence because of their belief system. I feel like we’re going backward in history.

What’s next?

I’m writing a book. Focusing on thinking about what all these experiences have meant: with animals, trees, deforestation, endangered wildlife, wildfires, climate change, sea-level rise, ice. What does it all mean? There are stories upon stories upon stories and those are going into the book. But, what does it mean in terms of the shift of my perception and consciousness in relation to the time in history that I’m looking through? That’s what I’m trying to put into words in this book.

Read More: Will Sundance Film Festival Choose Boulder?