The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

On a cool late-spring day, lifelong farmer Dan Crouch looks out over row after row of still-green wheat as he contemplates the July harvest on his land 40 miles east of Denver. Sixty-seven-year-old Crouch reminisces for a moment. He still remembers the old days when his family tilled the soil and didn’t use fertilizer.

But farming is different today. Tilling has long been considered unsustainable in Colorado because of the dry climate, and Crouch, like many farmers, began adding fertilizer to his fields about 25 years ago. At first he used anhydrous ammonia, but over the years, he learned the chemical fertilizer had multiple drawbacks: The big problem, aside from its hazardous properties, Crouch says, is, “All you get there is nitrogen. There’s nothing else in it. And it’s expensive.”

So he started looking for alternatives—and, about 10 years ago, found one called Metrogro. In addition to supplying the necessary nitrogen, it’s rich in phosphorus and zinc, nutrients critical for plant growth. “It has measurably improved my soil,” Crouch says, which has in turn improved his crop and, at times, his profit.

The soft-spoken farmer is not alone in his support of Metrogro, which is permitted for use on nearly 400 Colorado farms that grow much of the state’s wheat, as well as tons of commercial grains such as corn and millet. But Crouch and other Colorado farmers can’t buy Metrogro from their typical agricultural suppliers. Metrogro is what you might call a special-order product—one that’s produced by, of all places, the facility that treats Denver’s sewage.

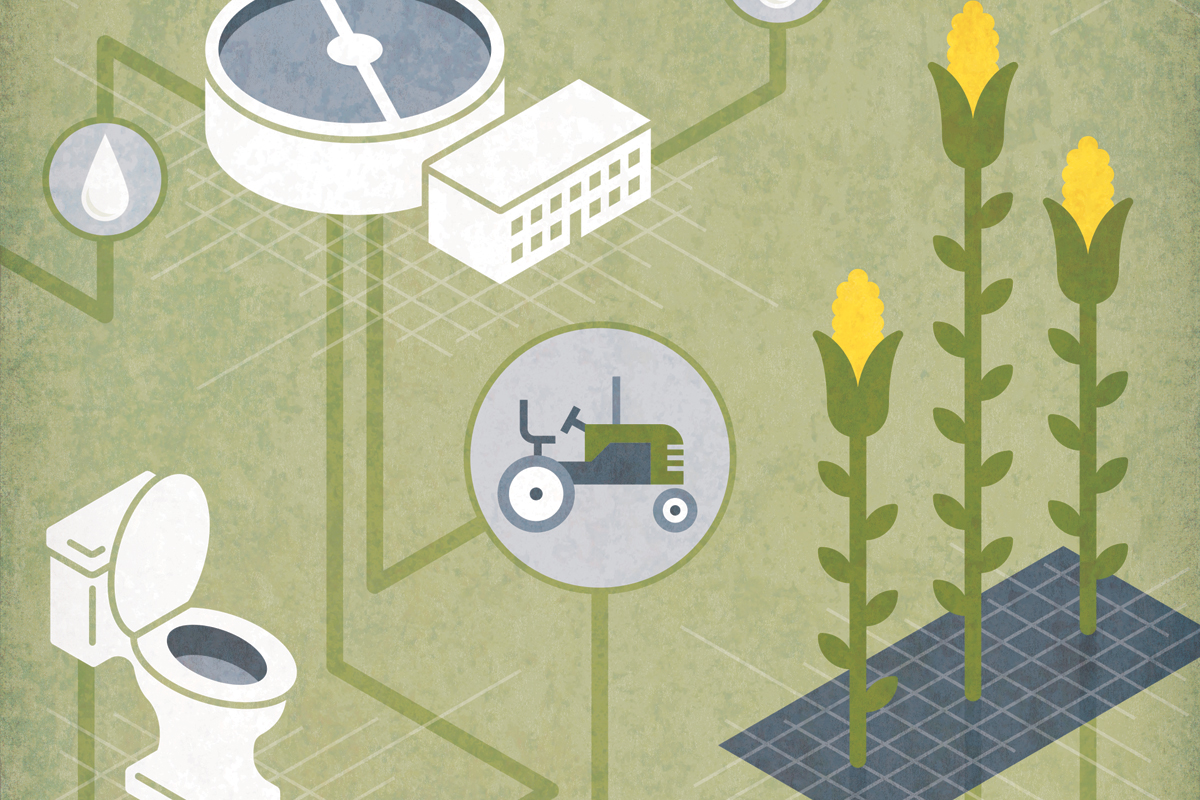

Yes, you read that right. Metrogro, which does a miraculous job of closing the nutrient-recycling loop by restoring to the soil minerals essential to crops, is made of “biosolids,” which is really just a fancy—and more palatable—way of saying highly treated human waste.

When Denver residents flush their toilets, take showers, or run the disposals in their kitchens, the water and other waste—feces, food scraps, hair—disappear and, less than 36 hours later, come pouring into an intake channel at the Metro Wastewater Reclamation District in Commerce City. Standing over an intake, the swift current looks like muddy river water and has an odor reminiscent of a restroom at Folsom Field on a hot September day. The water then enters the treatment plant, which works the same small wonders as wastewater treatment plants around the country. After the mixture is biologically treated and disinfected, the remaining water is clean enough to be discharged into the natural environment: in Metro’s case, the South Platte River.

Left behind at the plant are the solid materials. After the larger debris—rags, toys, the occasional false tooth—are removed, the solids are sent to anaerobic digesters, massive domes in which microorganisms consume the waste. The digestion process kills off bacteria and, after the removal of any remaining liquid, produces a nutrient-rich, soil-like material—biosolids—that farmers like Dan Crouch can use in their fields. Because his wheat could end up in the toast on Colorado’s breakfast tables, there are regulations to ensure the fertilizer is safe. Crops like wheat, for example, can’t be harvested for a certain number of days after biosolids are applied to the soil.

According to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, about 80,000 dry metric tons of biosolids—of the 85,000 total produced—in Colorado were reused in 2012 for land application or composting. That’s a recycling rate of more than 90 percent, which exceeds the national average of 55 percent reported in 2007, the latest figure available.

Proponents of biosolids say it is prudent to use every available ounce of the material we consider waste, especially because a popular alternative is to produce nitrogen from natural gas and mine phosphorus—both limited resources—for chemical fertilizer, which causes environmental damage and isn’t as healthy for the soil. Detractors, such as Caroline Snyder, professor emeritus at the Rochester Institute of Technology and one of the nation’s most outspoken critics of biosolids, say that calling human waste “biosolids” is just a euphemism—a public relations ploy—used to pawn sewage sludge onto farmers rather than come up with safer ways to deal with it.

“We don’t think it’s recycling,” Snyder says of the group she chairs, Citizens for Sludge-Free Land. “We think it’s transferring industrial chemicals to rural farmland.” She contends that pathogens are not fully killed off by the treatment process, posing risks of infection as well as respiratory and gastrointestinal problems, and that chemicals that enter the waste stream—from factories or hospitals, for example—are not eliminated during treatment, which means compounds we typically deem hazardous could be entering the soil and subsequently the food chain. There are also reports—although they’re mostly unconfirmed—of human illnesses and deaths being linked to exposure to sludge. As such, critics would instead like to see sludge burned for energy, sent to a sanitary landfill, or used in mine reclamation—options that mostly keep it away from people.

Ken Barbarick, a professor of soil science at Colorado State University, disagrees. Barbarick has studied the impacts of biosolids on soil and crops for more than 30 years. “Everything we’ve found has been positive,” he says. “Biosolids turn out to be an excellent source of nitrogen, phosphorus, and zinc, which our soils need in Colorado.”

Barbarick says potential issues could arise from the over-application of biosolids, which might cause problems such as nitrogen build-up in the soil and nutrient runoff. But there are county, state, and federal regulations in place to ensure that doesn’t happen, including permits and rules requiring designated companies to execute the actual application. Crouch, for example, doesn’t apply Metrogro himself. Instead, in accordance with regulations, Paul Ferguson, Metro’s land application coordinator, makes sure his staffers carefully spread the material only where soil has tested low for nitrogen. Biosolids produced at other wastewater facilities are similarly applied, or in some cases, subcontractors purchase the biosolids and serve as middlemen who have the training to spread the product safely. Limon-based Parker Ag Services, for example, has permits to apply biosolids it gets from facilities across the state to about 25 farms totaling approximately 100,000 acres—twice the size of Mesa Verde National Park.

As natural resources get tighter across the United States, the trend to reuse whatever we safely can is expanding. Colorado is following the lead other drought-threatened states such as California and Texas have taken in reusing the other major product that leaves wastewater treatment plants: water.

Although most of the treated water that leaves Metro Wastewater gets funneled to the South Platte River, some of it is sent to Denver Water—which treats it further in order to use it again. Recycled water makes up about three percent of Denver Water’s overall annual production. After an ongoing expansion is complete in 2025, the utility expects that amount to increase to five percent. “The key benefit for building this project is basically being able to save potable water,” says Jenny Murray, Denver Water’s recycled water program manager. “For every use that we can replace with recycled water, we’re able to save that water to meet our customers’ needs for drinking water.”

The utility is working with potential clients, including commercial car wash and laundry operations, who could use recycled water in their businesses. Xcel Energy uses recycled water for its cooling towers, and Denver Water partnered with the Denver Museum of Nature & Science on a heat pump project that uses recycled water. Damian Higham, Denver Water’s recycled water specialist, explains even the Denver Zoo uses it—for irrigation, animal swimming pools, and washing enclosures. “They’re certainly one of the greenest zoos in the country, and recycled water is a big part of that.”

Other municipalities are going a step further and using recycled water to replenish drinking water supplies, known as potable reuse—a relatively new process for Colorado that has been the norm in other states for years. Hit hard by the 2002 drought, the City of Aurora decided to engineer a potable reuse project, which began paying dividends in 2012. While the idea sounds shudder-worthy, Aurora Water director Marshall Brown says city residents embraced the project from the start.

Driven in part by the success of the Aurora program, other Colorado cities are now turning to water reuse. Water providers in places such as Denver, Parker, and Castle Rock signed onto a partnership last year that will allow some of them to draw on Aurora’s recycled water supply. And interest in reuse elsewhere is growing, says Eric Hecox, executive director of South Metro Water Supply Authority, a network of water providers that covers parts of Arapahoe and Douglas counties and helps its members implement reused-water projects. “Water’s scarce enough,” he says, “that there’s a high incentive to use and reuse every drop you’re legally entitled to.”

To farmers like Crouch, these brazen recycling efforts make sense. After all, water conservation is crucial for agriculture in Colorado. “If you get no moisture, it doesn’t matter what fertilizer you use,” he says.

Of course, Crouch concedes that certain types of reuse have their downsides. Biosolids, for example, are treated to kill bacteria, but they’re still a byproduct of sewage sludge—and no one’s going to be using them as air fresheners. Crouch says his neighbors haven’t complained much, though he admits a musty smell lingers for a few days after application. But he shrugs his shoulders and says, “Hey, that’s the smell of money if you’re a farmer.”