The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Like any attorney worth his wing tips, William Trachman understands the importance of telling a good story.

As general counsel for the Mountain States Legal Foundation, a public-interest law firm based in Colorado that frequently sues the federal government for meddling in Americans’ lives and livelihoods, he knows that it’s the emotional and financial ordeals of his clients, rather than the legal nuances of a case, that are likely to draw public attention. And a compelling narrative that embodies a constitutional principle—the right to free speech or to bear arms or to equal protection under the law—is even better.

“I’m the Constitution’s lawyer,” Trachman says. “We’re always going to try to tell a story with our cases: how someone who is sympathetic was injured by a law gone wrong and has a constitutional right to go to court to fight it. All our cases involve stories of people, not just us as lawyers.”

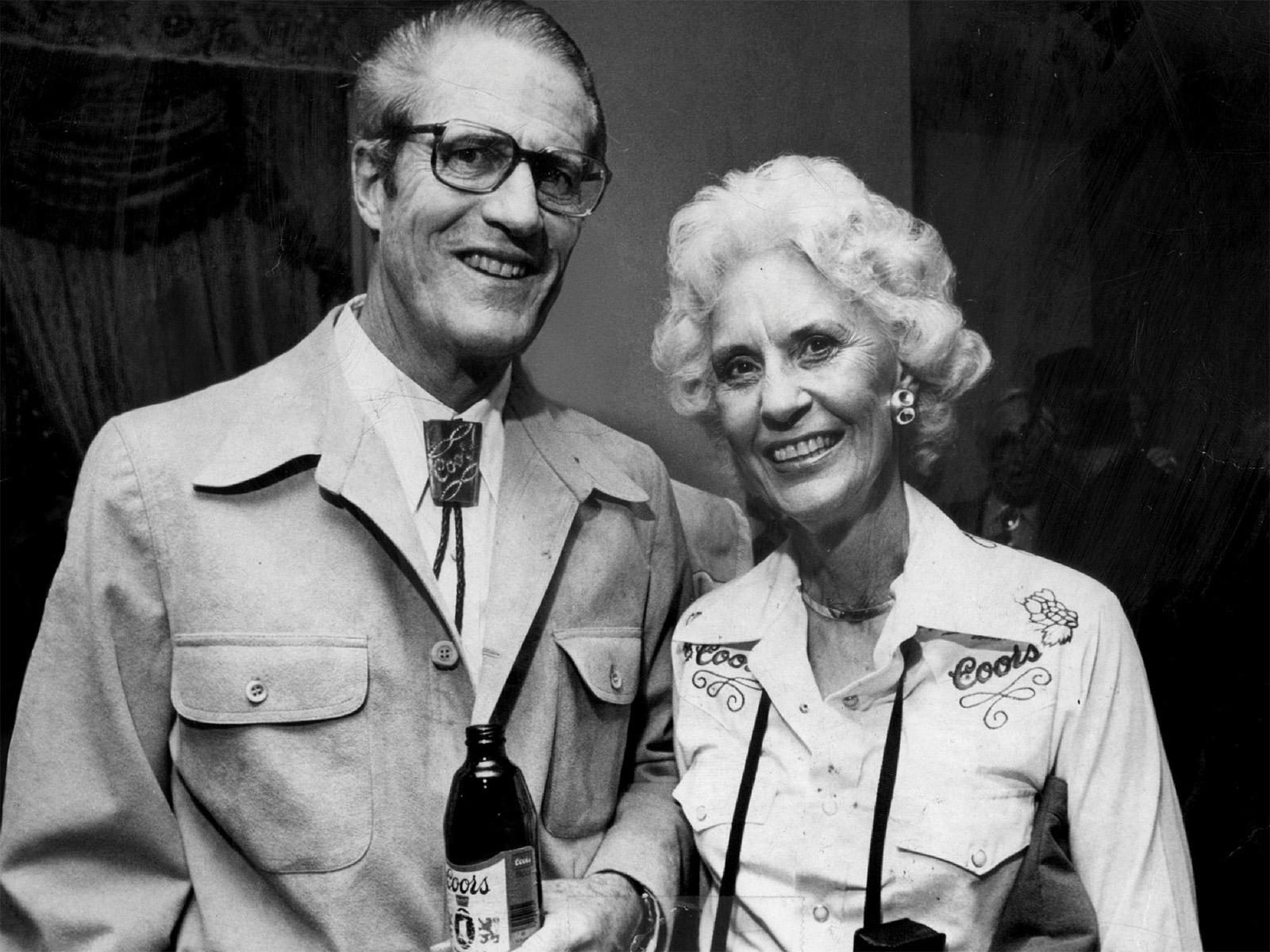

Launched in 1977 with seed money from beer magnate Joseph Coors, Mountain States has been a fixture of Colorado’s legal scene for nearly half a century. Yet the nonprofit remains better known in Washington, D.C., policy circles than at home, where it’s kept a relatively low profile—except when its crusades become too controversial to ignore. The most recent example of the small firm’s big reach involves one of its longest-running cases: a 2015 class-action lawsuit against the Federal Aviation Administration, filed on behalf of hundreds of white plaintiffs who claim that they were rejected for air traffic controller jobs because of a hiring process that was rigged to favor other racial groups, in violation of federal civil rights laws.

The suit dragged on through three administrations without attracting much notice. But in January, nine days into the second Trump presidency, a midair collision between a military helicopter and an American Airlines jet in Washington killed 67 people—the deadliest domestic air disaster in more than 20 years. Hours later, President Donald Trump accused the Biden and Obama administrations of running the FAA “right into the ground,” insinuating that the crash was the result of federal diversity, equity, and inclusion hiring programs. “They actually came out with a directive, ‘too white,’ ” Trump said. “And we want the people who are competent.”

Vice President J.D. Vance echoed Trump’s remarks and referred pointedly to the Mountain States lawsuit. “You have many hundreds of people suing the government because they would like to be air traffic controllers, but they were turned away because of the color of their skin,” he said. “That policy ends under Donald Trump’s leadership.”

The circumstances of the crash are still under investigation; preliminary reports indicate there may have been multiple causes, from helicopter pilot error to a shortage of personnel in the tower to communication issues. In media interviews Trachman did in the wake of the tragedy, he was careful not to draw a direct link between FAA hiring policies and the crash, but he acknowledges that the administration’s finger-pointing “drove a lot of traffic to our organization.”

The lawsuit is now going through mediation, and the outcome could have far-reaching implications. If the two sides agree to a settlement, “it will create a deterrent effect for the next administration,” Trachman says. If the mediation fails to reach a resolution and Mountain States is victorious in further court action, the case could set a precedent. “We’ll have a court decision that says you can’t racially gerrymander your workforce by tinkering with your application test,” Trachman says. “And that will apply not just to federal agencies but to every employer.”

The second Trump term would seem to be an auspicious time for the legal warriors at Mountain States. But presidents come and go, along with their flurries of executive orders. During Democratic administrations, Mountain States has been a hectoring voice in the wilderness; during Republican ones, it’s served as a recruitment pool for cabinet members and top advisers. Through it all, operating out of a nondescript office park in Lakewood, the organization has pursued its own agenda for America, marked by an exuberant embrace of private property rights, limited government, drill-baby-drill energy policy, anti-anti-racist activism, and similar objectives. Mountain States hasn’t always prevailed, but it’s been surprisingly effective at rallying support for its constitutional grievances, from hyperlocal public-school disputes to civil liberties battles that extend all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Unlike commercial law firms, Mountain States doesn’t charge its clients for its services. In some instances, it may be awarded fees and costs in a successful court action, but most of its annual operating budget (the firm reported $4.3 million in expenditures in 2023) comes from corporations, foundations, and individuals whose identities the group declines to disclose, citing privacy concerns. One-time, five-figure contributions from the Independent Petroleum Association of America, the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation, and the Armstrong Foundation have surfaced in public records, but the firm’s past and present leaders maintain that most of their funding comes in dribbles of a few hundred or a few thousand dollars from individuals who share their vision of personal freedom. According to data posted on its website, the average donation is $225.

“I feel blessed that people put that kind of faith in us,” Trachman says. “I’ve seen the criticisms—that we are a stalking horse for Koch Industries. I have never spoken to Koch Industries in order to get a $5 million check. The fact that we have a unity of interests with some of the energy companies isn’t a knock on our work. It just means we have an interest that’s good for the country that happens to dovetail with interests that are good for the private companies.”

As Trachman sees it, his mission is “expanding the blast radius” of Mountain States’ wins by establishing precedents that help to curb an overreaching bureaucracy. “The goal is creating something to point to,” he says, “that is going to survive us and create binding law.”

In the summer of 1971, corporate lawyer Lewis Powell fired off a hush-hush memo to a friend at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, declaring that the American way of life was under “broad attack” from left-wing extremists, ranging from Marxist academics and the Black Panthers to consumer advocate Ralph Nader and journalists at the major television networks. Powell, whose clients included big tobacco companies, wrote it was time for corporate interests to fight back “in all political arenas,” enlisting their own teams of scholars, speakers, attorneys, and others to defend the free enterprise system.

President Richard Nixon appointed Powell to the U.S. Supreme Court a few weeks later. Over the years, pundits have alternately pointed to the Powell Memorandum as a blueprint for plutocracy and dismissed it as a quaint rant, but it’s clear that it resonated with several influential backers of conservative causes. One was Joe Coors, whose family brewery business in Golden had its share of tussles with unions and bureaucrats. In 1973, Coors became one of the founding funders of the Heritage Foundation, a pro-business think tank based in Washington, D.C. Initially modest in scope, Heritage has since become one of the most powerful policy groups on the right, a clearinghouse for ideas on how to restructure government and dismantle federal regulation of the private sector. Its periodically updated Mandate for Leadership policy guides are widely regarded as playbooks for Republican administrations. (The latest version is better known as Project 2025; Trump has attempted to distance himself from the 992-page document while implementing many of its recommendations.)

Not content with bankrolling a think tank, Coors also invested in a boutique, public-interest law firm that could challenge government policies in court, donating $25,000 in startup funds to the Mountain States Legal Foundation. A group called the National Legal Center for the Public Interest (which has since merged with the American Enterprise Institute, another conservative think tank) chipped in an additional $50,000. Originally, Republican backers hoped to establish a string of regional firms overseen by a national organization, but the local groups each had their own leadership and fundraising concerns—and their own hot-button issues. Some positioned themselves as champions of gun rights or defenders of free speech in the marketplace and on campus. Mountain States prioritized natural resource and environmental regulation battles with the federal government, which controls nearly a third of the land in Colorado and New Mexico and much more in other Western states.

Coors’ choice to lead Mountain States was James Watt, an attorney who had grown up on the high plains of eastern Wyoming before spending much of his career at various government posts inside D.C.’s Beltway. In the firm’s early days, Watt set about filing “friend of the court” briefs in other firms’ cases, the kind of cases that attracted donor support from right of center: an Idaho plumber who refused to let government inspectors into his shop without a warrant, an attack on affirmative action at the University of Colorado School of Law. Soon Mountain States was initiating its own lawsuits, targeting the Environmental Protection Agency, the Sierra Club, and other foes. (One early case challenged the EPA’s authority to regulate air pollution—aka the notorious “brown cloud”—in Colorado.) In its first four years, the foundation’s annual budget grew from $194,000 to $1.2 million.

Read More: Is Frank Azar Colorado’s Greatest Lawyer?

At the urging of Coors and other influential Westerners, President Ronald Reagan asked Watt to head the Department of the Interior in 1980. The so-called Sagebrush Rebellion—a political revolt by mining, ranching, and fossil-fuel interests over Carter-era environmental regulations that limited their access to millions of acres of public lands—was in full bloom. Reagan vowed to ramp up oil and gas production, as well as coal and water projects, but retooling a bureaucracy as ponderous and politically charged as the Interior Department was no easy task. Watt was a polarizing figure in the debate, given to intemperate remarks about “extreme environmentalists” and their plot to “weaken America” by blocking energy production in wilderness areas. (Another Watt zinger: “I don’t use the words ‘Democrats’ and ‘Republicans.’ It’s ‘liberals’ and ‘Americans.’ ”) His combativeness alienated moderate elements in Congress, as did the fact that he had been the driving force behind Mountain States, which, according to a Rocky Mountain Magazine reporter, had “the reputation of being anticonsumer, antifeminist, antigovernment, antiblack, and above all, antienvironmentalist.”

Watt’s stormy tenure at the Interior Department was cut short by an insensitive remark—an off-the-cuff reference to what today might be called DEI. In a 1983 speech to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, he boasted of the diversity of an advisory panel he’d formed that had “every kind of mix you can have. I have a Black, I have a woman, two Jews, and a cripple.” He resigned a few weeks later.

Watt’s departure from the Interior Department seemed to take the steam out of the Sagebrush movement. (His fall from grace didn’t end there; his subsequent work as a lobbyist led to perjury charges in 1995 and a guilty plea to a single misdemeanor count of withholding documents. He died two years ago at the age of 85.) It also took the national spotlight off his former law firm. Mountain States continued to attract bright and capable lawyers—including Gale Norton, who worked there as a senior attorney in the early 1980s and later became Colorado’s attorney general and U.S. secretary of the interior under President George W. Bush—but the organization struggled to stay ahead of its bills.

By the time William Perry Pendley was hired as the group’s president and chief legal officer in 1989, Mountain States was on the verge of collapse. “I came in in March,” Pendley recalls, “and we didn’t know if it was going to make it through the summer.”

Another Wyoming native, Pendley had met Watt in 1977, shortly after graduating from law school. He was Watt’s attorney during the contentious confirmation hearings for the top job at the Interior Department and worked for him as a deputy assistant secretary for energy and minerals. He didn’t linger there long after his mentor left: “I was seen as a Jim Watt guy,” Pendley says now. But what might be considered a liability in Washington was regarded as an asset by Mountain States’ board of directors as they attempted to put the operation back on firm ground.

Pendley believed the firm needed to take on more cases that ignited the passions of its donor base—or, as he puts it, “Better cases, more money. More money, better cases.” Mountain States had developed a niche in natural resource issues across the West, but the typical case involved arcane land-use battles. The federal government would propose a new resource management plan, environmental groups would object, Mountain States would object to their objection, and so on. “It was important, but nobody cared about it,” Pendley says. “My view was, I’m going to take cases that involve real people who have real problems with the federal government.”

One of Pendley’s first clients was John Shuler, a Montana sheepherder who was facing a massive federal fine for shooting an endangered grizzly bear that was preying on his flock. Pendley saw a story about the case in a newspaper, called up Shuler, and offered to represent him at no charge. After an eight-year legal battle, in 1998 a district court held that Shuler had acted in self-defense. The case drew national media attention and convinced Pendley he was on the right track. “[Shuler] became the poster boy for Endangered Species Act reform,” he says.

Another early case began when Randy Pesh, a Colorado Springs subcontractor who supplied guardrails to road construction projects, walked into Pendley’s office. Pesh had submitted the lowest bid for a project in southwest Colorado, but he’d lost the job to another company because of federal incentives that favored “disadvantaged” or minority-owned businesses. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in a 1995 landmark ruling, greatly restricted the ways the federal government could use racial classifications to further government interests.

The victory whetted Pendley’s appetite for more flash-point cases. “If there was something that involved an important constitutional right, that had the possibility of garnering national attention and getting to the Supreme Court of the United States, I took it,” he says.

While suing the government is easy, winning isn’t. Pendley was unsuccessful in his efforts to get the Supreme Court to hear the appeal of auto racing legend Bobby Unser, who was convicted of operating a snowmobile in Colorado’s federally protected South San Juan Wilderness, despite the fact that Unser had been lost in a blizzard at the time and nearly died before finding help. But such cases still attracted press coverage and financial support. Pendley became the public face of the organization: a Sagebrush courtroom avenger decked out in cowboy boots and a gunslinger’s horseshoe mustache.

Pendley’s journey from the halls of government to a law firm dedicated to suing the government is hardly unique. Mountain States’ current president and CEO, Cristen Wohlgemuth, was once a policy adviser to Rick Perry when he was the governor of Texas. Wohlgemuth also worked for three years with constitutional scholar John Eastman at the Claremont Institute—the same John Eastman who is now fighting possible disbarment over his efforts to block certification of the 2020 election results. Chip Mellor, a former Mountain States attorney, went on to launch the Institute for Justice, a Virginia-based public-interest firm focused on constitutional issues. Another alum, Clint Bolick, is now a justice on the Arizona Supreme Court.

After almost 30 years at the helm of Mountain States, Pendley stepped down in 2018 and returned to Washington, where he served as the acting director of the Bureau of Land Management under the first Trump administration. He remains a highly visible pot-stirrer in the debate over energy and public-lands policy, having written a chapter on the proposed revamping of the Department of the Interior for Heritage’s Project 2025. Among the bolder moves Pendley recommended: scrapping Biden impediments to oil and gas leasing on federal lands, including the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; taking gray wolves and Yellowstone grizzlies off the endangered species list; and trimming the size of national monuments in Maine and Oregon. A Sierra Club analysis of the chapter prior to the 2024 election noted it proposed dozens of actions “that a future president could take to cripple climate action, remove wildlife protections, and curtail outdoor recreation.”

Read More: Is the GOP Dead in Colorado?

It wasn’t the first time Pendley’s thoughts on public lands had drawn consternation. In a 2016 article, he argued that the federal government has “a constitutional duty to dispose of its land holdings.” Pendley says his position has been misinterpreted by critics as a call to sell off national parks to developers, when he was merely making a case that the federal government has the authority to turn over properties to state control. But that position isn’t shared by his former law firm. Last year, Utah filed a lawsuit in an attempt to seize control of 18.5 million acres of “unappropriated” federal land—that is, land not already reserved for national parks, forests, or other designations. In a friend-of-the-court brief filed on behalf of the Wyoming state Legislature, a Mountain States attorney argued that national parks and monuments and other “appropriated” properties should also be included in any transfer. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

Steve Bloch, legal director for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, has skirmished with Mountain States in several public-land disputes—including, most recently, Utah’s land-grab lawsuit. “From a litigating standpoint, I don’t think of them as especially effective,” Bloch says. “The position they stake out on behalf of their clients is pretty wildly out of touch with what the vast majority of Americans want to see on federal public lands in the American West.”

Still, environmental groups say it’s impossible to ignore the firm’s political clout. In addition to Pendley, whose treatise for Project 2025 may have influenced recent Republican efforts to sell public lands or prioritize their use for extraction industries, they point to Karen Budd-Falen, a former Mountain States attorney who is now second in command at Trump’s Interior Department.

“The concern right now is that so many of these folks who have come up [through] Mountain States are once again in positions of power,” says Aaron Weiss, deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities, a Denver-based conservation group. “It would be a mistake to underestimate them. They are one of these groups that’s a bridge between mainstream Washington conservatism and this far right, anti-public-lands, Sagebrush Rebellion conservatism.”

William Trachman’s last day working for the federal government was January 20, 2021. Having submitted his resignation letter, he cleaned out his desk at the U.S. Department of Education’s regional office in Denver and left the César E. Chávez Memorial Building 10 minutes before the inauguration ceremony for President Joe Biden; someone had already removed the office photos of Donald Trump and Mike Pence. Eight days later, Trachman started his new job at the Mountain States Legal Foundation.

Growing up in Fresno, California, during the Ronald Reagan administration, Trachman remembers being fascinated by politics and the hoopla around presidential elections. His father was an admirer of the libertarian author Ayn Rand; his mother was “very left wing,” he says. He considered himself a libertarian in high school, but his politics shifted after the September 11 attacks: “I decided that the world was a rough-and-tumble place, and we needed to set aside our bleeding hearts and get tough.” He majored in political science as an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley, took his law degree there, clerked for a George W. Bush appointee at the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver, worked for a large firm in San Francisco, married another attorney, and then moved to Colorado.

After working as a defense attorney in employment cases, Trachman became the general counsel to the Douglas County School District, which was embroiled in a series of legal battles involving vouchers, open records, union disputes, and more. (“I was the beneficiary of a lot of that drama,” Trachman says dryly.) In 2017, after the district’s solidly conservative school board lost several seats to a more liberal contingent, Trachman moved to Washington as a Trump appointee. He spent two years there as a deputy assistant secretary in the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, rescinding Obama-era initiatives, before moving back to Denver to work at the regional office and then at Mountain States.

His background in education and employment made Trachman an ideal fit with the organization, given its long history of opposing DEI efforts. Since he’s been there, the group has expanded its activities in the equal protection arena, obtaining injunctions that put the brakes on three Biden administration programs. Two of them involved disaster and pandemic relief for farmers and ranchers that, Mountain States argued, favored certain applicants based on race or sex. The third proposed regulations that would have expanded school protections for transgender students and the use of preferred pronouns. The change in leadership in Washington this year may have doomed the programs anyway, but Trachman is wary of declaring victory too soon. “Executive orders don’t entrench a ruling like a court precedent would,” he says. “That’s why our suits have to continue.”

Read More: 2024 Election Results: How Colorado Voted on Key Races and Ballot Measures

Perhaps the most emphatic demonstration of the firm’s dogged persistence is its nearly decade-long battle with the FAA. The lawsuit’s origins date back to Obama administration efforts to boost the hiring of people of color and other underrepresented groups at the FAA, one of the least diverse agencies in the executive branch. The lawsuit contends that changes to the FAA’s hiring process, introduced in 2013, created a “race-skewed screening mechanism” that favored certain applicants—by, for example, awarding extra points for having low high school grades in science or being unemployed for five or more months in the past three years—at the expense of more qualified candidates.

More than 900 of the passed-over applicants are now plaintiffs in the Mountain States lawsuit. A Republican-majority Congress passed legislation in 2016 banning the FAA’s use of the biographical assessment. But the agency’s critics contend the Biden administration continued to promote diversity over merit and that the cascading effects of air traffic controller shortages and stress have created an ongoing crisis in the air. The day after the helicopter-jet collision, Mountain States published a blog post calling the accident “a sobering reminder of the cost of placing ideology over expertise.”

Biden’s secretary of transportation, Pete Buttigieg, has defended the former administration’s management of the FAA and called efforts to blame the crash on DEI initiatives “despicable.” Leaders of both parties have sounded alarms about short-staffing at the agency for years; some contend the problem dates to Reagan’s firing of 11,345 striking air traffic controllers in 1981. The FAA claims to have slightly exceeded its 2024 hiring goal of 1,800 new controllers, but its own data indicates that nearly half of its facilities remain understaffed—and that thousands of additional controllers are needed to bring the towers up to full strength.

The Trump administration has already issued orders banning DEI programs, and Sean Duffy, the current secretary of transportation, has stressed a need for “the best and the brightest” in the control tower. “I have a deep debt of gratitude to President Trump for spotlighting things like illegal DEI that have been a scourge on the country for four years,” Trachman says. “Highlighting that issue—not just in the sense that it’s morally wrong, but also that it’s dangerous to put people in positions with a high level of trust based on race or sex—that is something I will forever be grateful for.”

The new regime’s embrace of a cause that Mountain States has been litigating for years raises intriguing questions about the firm’s future. Will hardcore conservatives continue to support the organization’s efforts to limit the scope of government when the head of the executive branch seems unabashedly bent on tearing apart the entire apparatus from within? Do the corporate tycoons and billionaires who serve in Trump’s Cabinet really need a small Colorado firm out there crusading for a free marketplace? In short, are Mountain States and its contingent of attorneys still relevant now that their previously fringe causes have become mainstream? Former Mountain States chief Pendley concedes the return of Trump “may make it more difficult from a fundraising standpoint.”

Far from packing it in, the firm seems busier than ever these days. It continues to pursue a spate of its trademark little-guy-versus-big-government cases, including the plight of a Colorado Springs teen who was sent home from his middle school for wearing a Gadsen flag (“Don’t Tread on Me”) patch on his backpack, along with images of Pac-Man-type ghosts toting “ghost guns.” It’s Mountain States’ contention that its client’s First Amendment rights were trod upon.

In recent years, the firm has also beefed up its Second Amendment litigation, creating a special practice group (the Center to Keep and Bear Arms) “dedicated to helping you fight for your natural right to self-defense—from both man and tyranny.” The group challenged the government’s right to regulate guns built at home from kits, taking the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, only to be rebuffed by a 7-2 decision in March in favor of the feds. Another case, seeking to throw out a 2023 law requiring a three-day waiting period to purchase firearms in Colorado, is still pending.

Trachman says the foundation is also considering the launch of a Center for Energy Freedom, which would seek to “fulfill the vision of unleashing American energy production.” Battles over energy policy have been at the heart of the group’s agenda from the beginning, but Trachman thinks the next four years will be a critical phase of the struggle, as the Trump administration tries to impose its drill-baby-drill fever dream and states attempt to push back with their own regulatory schemes.

This year, Mountain States and Trump’s Department of Justice filed separate lawsuits attacking New York’s plan to create a “climate superfund” that would make energy companies pay for infrastructure projects that help the state adapt to climate change. The case is an indication that, whether in John Lobb wing tips or Manolo Blahniks or hand-tooled cowboy boots, the suits from Mountain States expect to be in court and in the fray, offering aid and comfort and expertise to the fossil-fuel crowd, much as they did for the Sagebrush rebels of yesteryear. “Don’t call it a comeback,” Trachman says. “We never left.”