The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

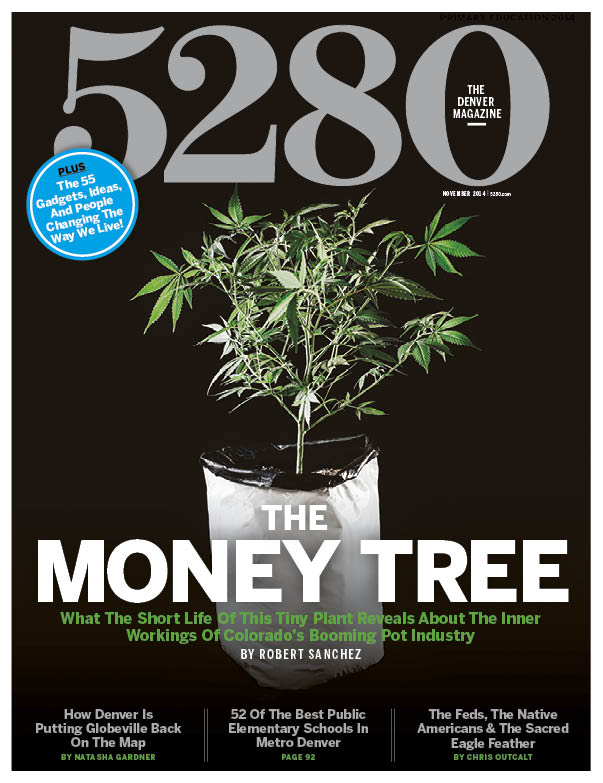

Forty forty-five begins as a wisp of green with leaves no bigger than a butterfly’s wings. On this morning in mid-January, it’s attached to the stem of a larger marijuana plant, number 3269, which is known more commonly by its street name, Strawberry Diesel—STD, for short—one of the most popular and productive cannabis strains sold in Colorado.

“What a pretty girl!” Kristina Imperi says as she runs her hands across the mother plant’s leaves. “This one’s perfect.” Dressed in a black cardigan, shorts, purple leggings, and leopard-print rubber boots, the 26-year-old Colorado Harvest Company (CHC) grow house worker kneels at the plant’s side and presses the tip of her trimming shears against the plant where the stem meets a branch. “Time to make some money,” she jokes.

Tim Cullen (above left) and Ralph Morgan (above right), who became business partners in the summer of 2011, are the two men behind Colorado Harvest Company and Evergreen Apothecary.

The space is bathed in cool light, which casts a bluish-green glow over the 220 marijuana plants lined up in the back room of this warehouse on Denver’s southwest side. Imperi makes a cut, and the first five-inch clipping falls away. She searches the mother plant for nine more “clones” and squeezes the clippers again and again. In less than a minute, a small bouquet of jagged-edged leaves blooms from her hand.

Taking a marijuana plant through its three-and-a-half- to five-month grow cycle is a time-intensive, exacting job from the first day. Pick the wrong plant to clone or fail to prepare it properly, and the results—anything from mold to mite infestations to less-than-stellar bud—can kill the bottom line. For cannabis companies like CHC and its sister business, Evergreen Apothecary, whose combined revenues are estimated to reach $7 million this year, anything less than perfection is pot heresy.

Imperi collects her 10 Strawberry Diesel clones in a plastic beaker, sets it on a bench, and pulls out the first clone. She trims a couple of leaves near the bottom, then cuts a half-inch off the tops of the two leaves she keeps. Imperi uses a razor blade to make a 45-degree slice across the base, then makes a vertical cut an inch higher. These last two cuts are where the plant’s roots will grow.

She grabs more clones and repeats the process. She dabs nutrient-rich purple goop at the base of each of the freshly cut clones and pops rubber stoppers around the middles. The clones are then plugged into Box 4, an aeroponic setup made from plastic and PVC pipe that holds up to 77 future plants and looks like a massive block of Swiss cheese. One by one, the STD clones and stoppers are put into their temporary homes, followed by others with names such as Jack-47, Herojuana, Juicy Fruit, and Sour Kush.

In two weeks, the clones will be transplanted into small containers. Five months later, the survivors from Box 4 will be packaged and sold. Among the superstars will be 4045, one plant among many that will help make the owners of this business very, very rich.

At Colorado Harvest Company’s grow site in Denver, 45 people care for the sprawling subdivisions of green—pruning, spraying, and feeding hundreds of marijuana plants each day until the buds eventually are cut, trimmed by hand, cured, dried, packaged, and sold. “It’s like Disney World,” says CHC grow manager Greg Fortemps. “For every person you bump into at the front of the store, there are four more making the magic in the back.” Since recreational shops started selling cannabis on January 1, CHC’s team has produced about 2,000 retail plants and turned the end products into everything from traditional, smokable pot to vaporizer-pen oils, topical creams, and edibles.

Combined with medical marijuana—which has been available to Red Card holders at licensed dispensaries since 2010—recreational pot in Colorado is estimated to pull in $47.7 million in tax revenue in fiscal year 2014 off $400 million in sales. More than $1 million of that tax revenue will come from CHC, which is considered a midsize weed business. While the overall financial haul is substantial for an industry still in its infancy, it doesn’t begin to capture the impact of cannabis in the state. By October, the Colorado Marijuana Enforcement Division had issued 18,666 occupational licenses; not all of the people who’ve obtained licenses work in the business, but many do (one estimate puts the number of pot workers at 12,000). That doesn’t take into account the electricians, plumbers, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning specialists who continue to benefit from the hundreds of marijuana retailers in the state.

Even if you’re not a hard-core stoner, it’s difficult to wrap your mind around the enormity of a grow operation—and the fact it’s all happening under the watchful eye of state and municipal bureaucrats. One day this past winter, I pulled up to the curb outside CHC’s 8,000-square-foot, cinderblock-and-concrete facility on South Kalamath Street. (The company plans to open two more grow sites before next summer.) A heavy, skunky aroma enveloped the block. I swiped my driver’s license on the scanner to the right of the glass-and-metal reinforced door out front. Inside, one of CHC’s co-owners, Tim Cullen, gave me a visitor identification badge and showed me a newly designed showroom that would open in a couple of weeks. We passed a “No One Under 21 Years Of Age Allowed” sign on the wall, then Cullen punched some numbers into a keypad and took me through a second door that opened to a small, climate-controlled hallway filled with dozens of budding marijuana plants. “Welcome to Colorado,” he laughed.

From the hallway, Cullen led me to the main flower room—with more than 150 bud-sprouting plants—then took me to the vegetation room, where plant number 4045 would begin its journey. Upstairs, in two smaller areas adjacent to CHC’s trim and drying rooms, another 100 or so recent clones had been removed from their aeroponic boxes and transferred into quart-size, plastic containers. Plants were on tables, on shelves, along the floor.

On that day, more than 500 plants were in various stages of life, growing behind the locked warehouse doors, guarded by an armed security staff, and watched by more than 30 video cameras placed around the complex. Even the metal trash bin out back had a lock on it, lest some enterprising pothead think there was gratis weed buried inside. (There isn’t.) The place was like the Fort Knox of ganja, and nearly all of the security measures are required by state regulators. When I asked Cullen if the regulations are onerous, he said, “The rules are complex, and there are a lot of them, but we’re always in compliance.” He paused and then added: “Whatever it takes, you know?”

Nearly two weeks after clipping the clones, Imperi gathers several dozen quart-size buckets, then hauls two 30-pound bags of coconut fiber to her work area. She cuts open a bag and fills several buckets with the barklike material. She pulls a rubber stopper off one of the Strawberry Diesel clones, digs a small hole in the coconut fiber with her fingers, and eases the plant into the first container. “I love creating life,” Imperi says. The plant is roughly eight inches from leaf tip to stem base, an important distinction for Colorado’s oversight of the product. Inside the aeroponic box, the plants are considered “immature” by the state. But now, in its container, the plant officially hits a state standard: more than eight inches tall and more than eight inches wide—a plant on the road to creating what the federal government considers a Schedule I drug.

From left to right: CHC plant number 4045 just before being moved into CHC’s flower room; the plants are arranged in wire “scrogs” for eight weeks, where they develop their telltale buds; the grow rooms at CHC are packed with plants, special lights, and ductwork that helps mitigate the pungent scent of the plants.

To record what’s been dubbed the “seed-to-sale” process, Colorado’s Marijuana Enforcement Division employs a first-of-its-kind computer system called Marijuana Enforcement Tracking, Reporting, and Compliance. METRC, as it’s commonly called, is a database that tracks all of the pot-producing plants and their eventual products in the state in real time—right down to the grams of shake that fall to the trim-room floor. The data is the state’s fail-safe, giving Colorado’s 30 marijuana enforcement investigators the ability to monitor an individual plant’s size and movement through a facility, all the way to a store’s final transaction.

If the process has a Nineteen Eighty-Four feel to it, that’s for good reason. With an estimated 130.3 metric tons of marijuana projected to be sold legally (or otherwise) in the state this year, Colorado has found itself in uncharted territory. “There isn’t a regulatory framework we could borrow coming into this,” says Lewis Koski, a former police officer who now oversees Colorado’s pot enforcement. “There’s nothing like it in the United States. There’s nothing like it internationally, in the world.”

Because of that, the weed business here has been in constant regulatory flux. At the moment, there are nearly 100 rules governing retail marijuana in the state, an ever-evolving list that mandates everything from prohibited chemicals to characteristics of the bag that’s given to a consumer after a sale. Koski says it’s sound practice to make sure the folks selling the pot are doing it aboveboard, while also letting weed opponents understand that legal pot production isn’t about to stop. “We’re implementing regulations around a very divisive public policy issue,” he says. “We’re at a very dynamic stage in the development of the industry.”

With the constant crush of customers, successful pot businesses today have an almost-mechanized, un-chill concern for process. At CHC, that means a religious schedule for lighting, watering, plant movement, and harvest. Perhaps most important, plants generally move as a unit from clone to cut to ensure a steady re-up in stores each week. Plants that fall behind never get a chance to catch up. Of the 77 clones from Box 4, Imperi scraps five runts—a five to 10 percent “kill” rate at the cloning stage is common—but the other 72 make it to containers. An hour and a half after she begins, Imperi plunges the final pot plant into the coconut fiber.

With the plants arranged on the concrete floor, Imperi transfers information from a hand-written paper into METRC and then to a software package called MJ Freeway, an internal tracking system that has features similar to the state’s program. After Imperi enters the data, she attaches radio-frequency tags to the plants, which will allow state enforcement officers to scan a bar code and access information about each plant. Blue tags are tied to those that will grow retail bud; yellow goes to medical plants. Of the maturing plants that make it into containers today, 51 get blue retail tags. Among them is 4045, which, to Colorado’s enforcement officers, will be known as 1A400021266FF40000000805.

The plant approaches the end of its short life; a close-up of the trichome-laden STD buds, which cost about $70 for an eighth of an ounce; product on the shelves at Evergreen Apothecary on South Broadway.

Five years ago, Tim Cullen quit his job as a high school biology teacher and opened Colorado Harvest Company, one of the state’s first medical marijuana dispensaries. Today, CHC is among the state’s more popular marijuana operations, and Cullen has the look of a man who’s enjoying life. The 42-year-old wears designer jeans; his custom shirts are left untucked, with the cuffs flipped up in a way that gives off an air of casual success. When he moves—through one of his grows, to a late lunch, to a meeting with one of his myriad potential investors—there’s an ease to his gait, a coolness, as if the world operates on his time.

One afternoon, he slides into the leather seat of his Lexus LS 460 (Cullen had the model number changed to read LS 420). His black Maui Jim sunglasses are propped atop his short salt-and-pepper hair. He starts the ignition and the groovy strains of a Grateful Dead song hum through the stereo speakers. A few seconds later, his phone rings. It’s a potential investor’s representative from Washington, D.C., whose client wants to dump millions of dollars into Colorado’s recreational weed market.

Because growing and selling marijuana is still a federal offense—the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency considers pot as dangerous as other Schedule I drugs such as heroin, ecstasy, and LSD—it’s difficult to get a traditional loan and impossible to patent marijuana or to acquire a trademark. “For the past 70 years it’s been a very one-sided conversation,” Cullen says. “People still think cannabis is being produced by dirty, nonshowering hippies, and that’s just not the truth.” Since CHC’s opening, Cullen has had seven bank accounts closed on him—four this year alone. All of which is to say independent financiers are essential to the industry’s development and ultimate survival.

“We want to be part of a growth operation, and that’s what you’ve done,” the woman on the phone tells Cullen. “We’ve been following what you’re doing very closely.” She asks general questions: about expansion, about security. Cullen answers some of her queries but is intentionally coy on others. After a few minutes, the woman hangs up. “I have no idea who that was,” Cullen laughs. “This is happening all the time now.”

I ask how much it would take for an investor to pique his interest. There’s no hesitation. “Five million,” he says. “Anything less, and it’s not even worth the time.”

That’s substantially more than Cullen’s initial startup costs following the 2010 law that expanded legalized medical marijuana in the state—or even the capital investment it would have taken last year for an already established medical grow to move into recreational cannabis. Just this summer, the city of Aurora made retail licenses available to 21 businesses at a cost of $15,000 per license. As in virtually any industry, the first movers into the market—the ones who took the biggest risks—are now the ones reaping the greatest rewards.

Equal amounts of luck, skill, and guile are built into Cullen’s story. Like many folks, he first was exposed to marijuana in high school, then experimented with the drug as a college student. He swore off illegal pot after he became a high school teacher in 2000; coincidentally, that same year Colorado voters approved Amendment 20, which allowed small, independent grows for medical marijuana users and caregivers who registered with the state. Amendment 20 was a hugely important step toward the legalization of recreational marijuana in Colorado; it essentially gave today’s growers their first government-sanctioned steps into what eventually would become a multimillion-dollar enterprise. Four years after the law was signed, Cullen began producing plants for himself and his father—both of whom suffer from Crohn’s disease. “It was a great feeling knowing I could help my dad like that,” he says. Over the next several years, Cullen tweaked his private grow, careful to never exceed the state maximum of six plants at a time, and racked up electricity bills that sometimes exceeded $400 or $500 a month.

Left to right: Colorado Harvest Company’s grow manager Greg Fortemps, grow-house worker Kristina Imperi, trimmer Jeremy Adamson, and trim manager Chris Weston all played crucial roles in the cultivation of Strawberry Diesel plant number 4045.

Six years later—following a federal memorandum from the Justice Department that said it was unwise to use resources to prosecute medical marijuana patients and caregivers—Colorado’s Legislature created the Colorado Medical Marijuana Code, which established a dual licensing system to regulate medical pot businesses at both the state and local levels. At the time, Cullen was staring down the next 30 years of his life as a teacher. “I felt I had to make the leap, or the opportunity might close forever,” he says. With $150,000 in retirement savings and maxed-out credit cards, Cullen started leasing the warehouse in southwest Denver and retrofitted it over 18 months. He brought in a business partner, hired his first three employees, and CHC made its first sale in February 2010.

By January 2011 Cullen recouped his initial investment and bought out his partner. A few months later, he joined forces with Ralph Morgan, another pot entrepreneur who ran Evergreen Apothecary, a successful storefront on South Broadway in Denver. Cullen had a production facility that had room for expansion; Morgan had a popular dispensary. The pair hired Greg Fortemps, a then-37-year-old grow-house manager with a business degree from the University of Denver, to ramp up CHC’s efficiency. “It was perfect,” Morgan told me not long ago. “Everything we needed to create a sustainable, long-term business was there. It was just on us to make it happen.”

By the time Colorado voters approved recreational weed in 2012, Cullen and Morgan were already in the midst of their own marijuana expansion. They added grows and hired 15 more employees. Morgan co-founded Organa Labs, a company that takes pot leaves and processes them into extracts. He eventually sold off half of that business, and he, Cullen, and several others launched O.penVape—which manufactures a popular odorless vaporizer—in late 2012. In part because of their successes, he and Cullen had the capital to purchase two more warehouses.

The company expects to spend $2.5 million in payroll this year—its 45 dispensary employees average $17 an hour—and all workers get two weeks of paid vacation, plus maternity and paternity leave. “The marijuana world is so dramatically different today,” Cullen says in his car. “Now we’re employing all these people. We’re expanding.” He presses the accelerator and the engine whines over the stereo. “I’m the former teacher who’s driving around in my badass Lexus, listening to the Grateful Dead. That’s pretty damn cool.”

Although there’s no photograph of the first clone that started Cullen’s miniature marijuana empire, the plant that begot number 4045 started 14 years ago as one of a dozen seeds smuggled from Amsterdam to Denver in the pant leg cuff of a friend of a friend. (One amusing fact of Colorado’s legalized pot industry is that every medical and recreational joint smoked in the state today is likely descended from one or more plants procured through illegal means.) Unlike some grows that employ a single “mother” to produce hundreds of clones of one strain over multiple years, Cullen’s production method is based on a succession of plants that produce the next generation while also manufacturing the next high—a decision he says saves space and optimizes the chance for healthier plants.

After acquiring his seeds in 2004, Cullen grew his first Strawberry Diesel under the caregiver law, then pushed the plant into wider production with CHC’s opening in 2010, before rolling it out on the recreational side this year. With that lineage, it’s possible the company’s present-day Strawberry Diesels are the 50th—or older—generation to develop under Cullen’s watch.

STD’s buds can grow to the size of “a forearm,” according to Fortemps, and the smoke has an intense, pungent smell. Connoisseurs appreciate the light strawberry notes but especially enjoy the thick, back-of-the-throat burn that gives the Diesel its kick and its fast-acting, energetic high. STD is a hybrid, meaning it’s derived from two different plants: sativa, which historically was grown in equatorial countries such as Colombia, Mexico, and Thailand; and indica, which developed in places like Afghanistan, Morocco, and Nepal. The former tends to give more of a “head high” and is considered more cerebral and conducive to creativity; the latter is more sedative and often leads to long couch sessions of TV-watching and Cheetos-eating.

CHC produces Strawberry Diesels that have yielded up to 10 ounces of product—worth roughly $3,000 in today’s market. As with all pot, the buds are packed with tetrahydrocannabinol, marijuana’s primary psychoactive ingredient. THC is one of about 60 compounds in marijuana and is stored in thousands of sticky, glistening glands. The glands, called trichomes, look like sugar crystals to the naked eye; under a microscope they appear as carefully arranged dewdrops. As they age, the trichomes darken with THC and cannabidiol—a nonpsychoactive compound prized by medical growers and most popularly used in the Charlotte’s Web strain, which can reduce the incidence of seizures in children. The trick for growers is to figure out the optimal time to harvest their buds in order for them to produce the desired high. “We’re trying to condition them to be the best athletes in the world,” Fortemps, the grow manager, says. “We want them to be Olympians.”

Because the pot plants are clones, the genetic characteristics are already sealed. It’s the grower’s challenge, then, to come up with a strategy that maximizes each plant, that squeezes every bit of potential—and cash—from its genes. “We’re pushing the limits, seeing what we might be able to create,” Fortemps says. But pot growers face myriad challenges other farmers don’t have to deal with: Namely, the federal government considers marijuana a Schedule I drug, which means the feds classify it as having no accepted medical use, and strict constraints exclude it from many scientific studies.

Despite the difficulties, growers have discovered that even the smallest tweaks to a pot operation can net impressive results. Fortemps and his staff, for example, have boosted overall bud production by nearly 75 percent in the past three years, in part by maximizing the number of plants that can be grown at one time, fine-tuning lighting technology, and tinkering with environmental factors such as humidity. Recent tests on Strawberry Diesel put its THC level at 20.86 percent—anything above 20 percent is considered high—and CHC markets STD to customers alongside its other high-THC strains, including Bruce Brainer, Headband Kush, and Mob Boss.

Of course, not every plant is a success. Plants are scrapped in the middle of the process—or worse, reach flower and produce an underwhelming yield. “Just when you think you’ve got it, this business has a way to humble you,” Fortemps says. “You take two clones off one mother, and one’s good and one’s bad. It’s like one goes to prison and the other becomes a CEO. Sometimes, you just don’t know.”

Between cloning and growing, 4045 is constantly on the move. It’s put in the two upstairs grow rooms for four weeks, then transferred to the main vegetation area, where it’s transplanted from its quart-size container into a five-gallon bag and put on a strict 18-hour-light, six-hour-dark schedule. In April the plant grows to more than three feet and Imperi takes seven clones from it. By May the plant stands at 48 inches.

Like some folks in the warehouse, Imperi began her career in landscaping but found the inconsistent schedule and off-season unemployment a constant financial—and emotional—burden. In 2012, she got her required background check and joined CHC after she met co-owner Ralph Morgan. Her parents, both of whom live in Boulder, are supportive of her career. “It’s some of the other people you meet, friends’ parents sometimes, where you don’t give away a lot about what you do for a living,” Imperi says. “I don’t want to feel judged.” It’s a typical refrain: the struggle between being a productive, tax-paying citizen and the feeling that what’s going on behind the reinforced doors still needs to remain in the shadows.

A gray-haired trimmer who took the job to help ease himself into retirement told me how he’d kept his job a secret from some friends for fear it might hurt his wife’s business. One gardener didn’t want his name used because it was so unusual that it’d be guaranteed to show up on the first page of a Google search. But Fortemps says that the fact he works at a cannabis business won’t change how he discusses weed with his two children as they get older. “I’m not going to be the guy who says it’s OK for them to smoke when they’re 16,” he says.

In late May, Imperi and two other grow-house workers move 24 of the 72 plants from Box 4 into the yellow light of the flower room. Here, more than 150 plants are nearing the ends of their lives. For the first two weeks inside the room, they’re given regular feedings of a nutrient-rich cocktail to help promote bud growth. On the third week, their leaves are cleaned and they’re thinned out. On the seventh week, the plants are flushed and put on a strict, water-only diet until they’re finally chopped down. “They can feel it coming,” one of the grow-house workers tells me as we stand in the flower room one morning. “They know they’re done.”

Fortemps puts on black gloves and squeezes one of the 30 or so buds on 4045. He gives a sniff. “Oh, yeah,” he says and closes his eyes. “This is going to get someone so high.” It’s mid-June and the plant is now nearly five feet tall; many of the buds are between three and five inches long. They’re so heavy they appear ready to snap the plant’s branches.

It takes about five months to grow 4045 but only a couple of minutes to cut it down. Chris Weston, one of the trim managers, moves in with a plastic bin and gardening scissors. He makes a few snips then gently pulls off the branches and bud. When he’s done, all that’s left is a skeleton of green and yellow sticks protruding from the five-gallon bag. Weston cuts the METRC tag from the base of the plant and then tosses it into the container with the buds.

The harvest initially weighs in at 1,726 grams—roughly 61 ounces. After trimming and drying, it’s common for a harvested plant to lose about 85 percent of its weight, which would put 4045 at around eight ounces. Gretchen Gonsch, another CHC trim manager, records the weight on a piece of paper, enters the numbers into METRC and MJ Freeway, and gives the plant to Jeremy Adamson, a thin, soft-spoken trimmer with a red beard. Today, Adamson’s dressed in a T-shirt and jeans covered by a blue smock that hangs off his slender body like a curtain. His trim table is almost entirely empty, except for two energy drinks, an LED desk lamp, and an 80-sheet composition book labeled “Weed.”

While Adamson works on the Strawberry Diesel, two women on the other end of the room roll joints and put them in bright pink, green, and yellow tubes. Gonsch operates the scale and calls out weights to workers who’ve turned in their product. The numbers are followed by nods and little whoops from the five trimmers. Each of the employees is paid by weight: A good two-week period generally nets about $1,000 per trimmer, while an excellent two weeks can bring in $1,700.

After 4045 is harvested, the buds are dried on a hanger, stored in a glass jar, and weighed one last time. Forty forty-five’s final weight comes in at 234 grams, or about 8.25 ounces, which is higher than average for CHC’s STD strain these days. The jar is moved to the other side of the room, where a woman parcels out eighths and sixteenths and puts them into childproof plastic canisters on a table. When the woman finishes, she steps back and starts to count. All told, there are 89 canisters on the table.

At Colorado Harvest Company the next week, a bearded, broad-shouldered former Marine swipes his driver’s license at the door and enters the shop. Richard,* a regular customer, knows most of the storefront employees—colloquially called “budtenders”—who greet him from behind stainless-steel countertops.

The showroom has a clinical-chic feel. Classroom beakers and microscopes (the better to see the crystallized THC) are juxtaposed with cafelike chalkboards advertising prices for eighths and sixteenths. Marijuana-infused mints are neatly stacked next to the cash register. Richard tugs on his beard as he looks through the store for a few minutes—“I’m a two-joint-a-day guy,” the 40-year-old says—and settles on the Strawberry Diesel. Alex, one of the tenders, pops open the black canister. It’s 4045.

“Nice, huh?” Alex says.

Richard doesn’t ask questions. He pays $72.67 for an eighth of an ounce, 22 percent of which is taxes. Alex drops the canister into a black plastic bag, then heat-seals the package. Within a few minutes, Richard’s out the door and in his Subaru.

Back at his apartment, he pours a glass of water in his kitchen, then settles on the couch in the family room. Despite the image of the pot-smoking slacker, many legal recreational marijuana users in Colorado are exactly like Richard: middle-age-ish white men with college degrees. Richard is studying to become a nurse and volunteers on the weekends with local charities. When he realized his apartment complex didn’t have an American flag, Richard found a pole, dug a hole in the courtyard, and poured the concrete himself.

He tears open the black bag with a key and opens the container. Richard crushes some bud between his thumb and index finger, then spreads it onto a piece of paper he’s folded in half. He pulls out a translucent, prerolled smoking paper. “I’m not into the equipment,” he says. “I don’t even have a bong.”

Richard packs the marijuana into the joint using the tip of a small screwdriver. He puts one end of the joint in his mouth, cups one hand over the business end, and fires up his lighter.

On a Tuesday in late September, Weston pulls a bag of packaged Strawberry Diesel bud off his desk in the trim room. “This is it,” he tells me. What Weston means is these are the roughly two ounces that are left of KR1916, one of seven clones taken from 4045 four or five months earlier. Forty-forty-five grossed about $1,500—roughly $330 of which was sales tax that eventually would make its way to the state’s department of revenue and to Denver. Its offspring would potentially bring in even more cash.

Across the hall, Imperi’s digging through a skunk forest. Buried behind clusters of Madness and Sour Alien is the clone of one of 4045’s clones. In other words, this is

a granddaughter. There’s more. Throughout the warehouse are remnants of 4045: The first-floor vegetation room has at least four Strawberry Diesel plants—the great-granddaughters. And across from those—next to aeroponic Box 4—is 2962, a great-great-granddaughter.

Imperi opens the door to the flower room. Under the yellow light, she discovers two more clones—the daughters of the original seven. One will be harvested tomorrow; the other the following week. “The circle of life,” Imperi says, then picks off a few leaves from one of the plants. “It’s kind of beautiful, isn’t it?”