The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

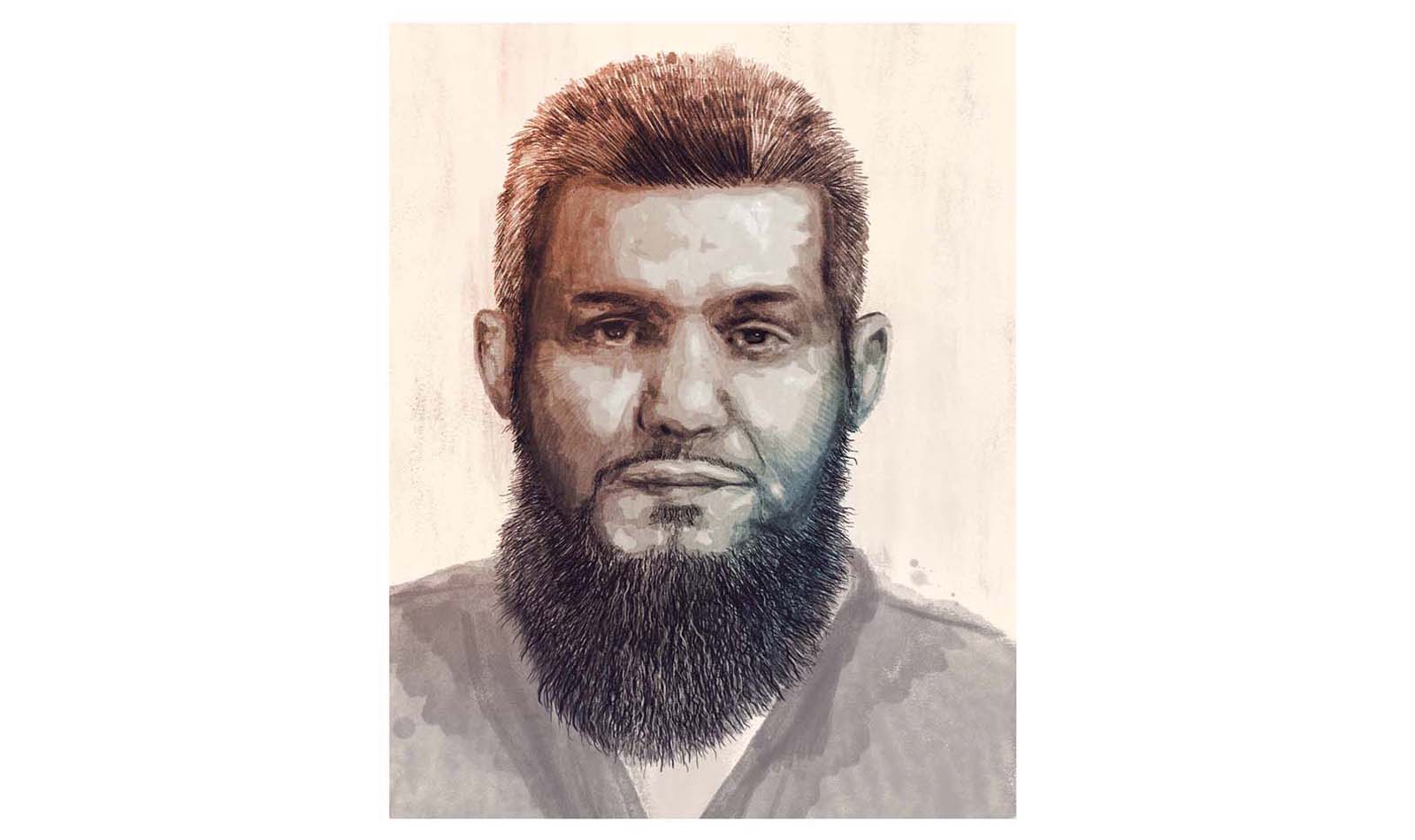

The law enforcement officer pulled off East Hampden Avenue and eventually turned onto East Lehigh Circle, a tree-lined street in a suburban Aurora neighborhood a few blocks east of Cherry Creek State Park. The individual, a U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) special agent, had a list of approximately 30 questions sanctioned by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and intended to pose them to a resident of one of the homes on the block—a short man with black hair and a neatly trimmed beard named Homaidan al-Turki.

It was an overcast Monday in early December 2001, not yet three months removed from one of the most terrifying and deadly events in American history. On the morning of September 11, in a span of 17 minutes, a pair of Boeing 767s struck each of the World Trade Center towers, causing the iconic buildings to collapse into rubble on the streets of Manhattan. A third plane crashed into the western side of the Pentagon; a fourth, perhaps bound for the White House or the Capitol, crashed in a field outside Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after passengers interfered with the plane’s hijackers.

No one immediately claimed responsibility for the attack; however, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), led by then Director Robert Mueller, identified 19 men involved in the hijacking of the four planes, 15 of whom were from Saudi Arabia. The agency traced their connections to al-Qaida, a terrorist organization headed by Osama bin Laden. Speaking to Congress a week later, President George W. Bush declared a global war on terrorism. The U.S. military, along with British forces, launched air strikes targeting al-Qaida camps in Afghanistan in October 2001.

On the one-month anniversary of the attack, Attorney General John Ashcroft appeared on ABC’s Nightline to discuss evolving intelligence and the government’s continued efforts to prevent acts of terrorism in the future. Seated across from journalist Ted Koppel, somewhere in the depths of the Justice Department, Ashcroft said the FBI was sorting through more than 200,000 tips the agency had received via its tip line and website. Ashcroft also explained that he was intent on developing a new culture of prevention within the federal law enforcement community. “So much of our efforts in the past have been devoted to prosecution,” he said. “We haven’t forsaken that as an objective, but our priority has to be to prevent, to curtail, to disrupt, to interrupt—to keep from happening again the kind of event that can take another 5,000 lives.”

Not long after the Nightline interview aired, in an apparent effort to make good on that shift, Ashcroft issued an order directing the FBI and other law enforcement agents to interview at least 5,000 legal immigrants, mostly Muslim and Arab men. The program, the attorney general later said, was designed to “expand our knowledge of terrorist networks operating within the United States.”

That day in Aurora, the INS agent had no trouble contacting al-Turki. A 33-year-old husband and father of five, al-Turki had come to the United States years earlier from Saudi Arabia on a student visa to study linguistics at the University of Colorado Boulder. After a few pro forma questions concerning al-Turki’s contact information, driver’s license, and passport, the interview turned to terrorism.

The officer asked al-Turki if he had any knowledge regarding the events of September 11, 2001, or if he knew anyone capable or willing to carry out acts of terrorism. Al-Turki replied that he did not. There were also questions about financing terrorism, training for terrorist activities, and knowledge of terrorists overseas. At one point, the officer asked al-Turki question number 20c on the prescribed list: “Does this person have any ideas as to how future terrorism can be prevented?” The agent noted al-Turki was “cooperative and honest.”

Three years later, the ACLU would admonish the government for these interviews, which it contended amounted to racial profiling. Former FBI agent Michael German, who retired in 2004 after 16 years with the bureau and has been critical of some of the agency’s post-9/11 work, described Ashcroft’s interview program as both inappropriate and ineffective. German has argued the effort seemed to be designed more to intimidate its subjects, rather than to actually gather information. “Do you expect you’ll knock on a door and Osama bin Laden Jr. will answer and say, ‘Ah, you got me?’ ” German says. “It was very dehumanizing; it treated the [Muslim] community as if it was a monolith.”

During the questioning on that winter day, al-Turki told the agent he had a handgun and a hunting rifle in the house; he said he’d inherited them from a Saudi national who was leaving town and didn’t want the weapons anymore. As for terrorism, al-Turki said he didn’t know anything about it. He even offered to aid the government by volunteering his skills as a translator.

The following day, the agent typed up a report on Homaidan al-Turki that included a cover sheet titled “Attorney General Interview Project.” The entire submission would be faxed to the National Security Unit headquarters in Washington, D.C. The sheet included a line labeled “FBI Interest Expressed.” The agent circled the word “No.”

One of 11 siblings, al-Turki grew up in Rafha, a small town in northern Saudi Arabia near the Iraq border. Even when he was a child, al-Turki’s friends, family, and members of the community viewed the boy as a gifted communicator. He had a talent for picking up languages quickly and was known for being affable and connecting easily with others, regardless of their ages. During the first Gulf War, when President George H. W. Bush stationed troops in Saudi Arabia, al-Turki would stand in front of his father’s home appliance shop and hand out pamphlets about the local culture to American soldiers.

After finishing high school and completing undergraduate degrees in English communication, linguistics, and English literature in Saudi Arabia, al-Turki was interested in furthering his education and moved to Colorado in 1992 to pursue a master’s degree. His wife and children moved with him; they also later brought over a housekeeper, an Indonesian girl who’d worked for the family in Saudi Arabia. Al-Turki eventually finished near the top of his master’s class at CU Boulder, which earned him a slot as a Ph.D. candidate at the school.

From the time he arrived in Colorado, al-Turki was active in the Muslim community along the Front Range. He was a key member of the Denver Islamic Society, an Islamic center and gathering place, and regularly invited friends and acquaintances to his house for meals. A longtime confidant, Ahmed Alshadooki, recounted one particular moment of generosity. “One of many events I will always remember about Homaidan,” Alshadooki wrote, “was when he stood up during the first week of Ramadan in 2003 at the Saudi student club and informed us that he and his wife, Sarah Khonaizan, were inviting all the members to breakfast every Monday at their house…. It was a warm touch during a very cold Colorado winter.” After each of the meals, Khonaizan set to-go boxes on the table so those who attended could take the leftovers home to their families.

Al-Turki’s children—a son and four younger daughters—enjoyed growing up in Colorado. They were raised with a decidedly Western mindset; in fact, three of the children were born here, arriving into the world as American citizens. Al-Turki’s son, Turki al-Turki, says his father was passionate about his studies; in the evenings, al-Turki would practice the pronunciations of various words in different languages while recording himself. On the weekends, though, he took his family to explore the outdoors. They camped in the wilderness near Vail and hiked through the red rock formations outside Colorado Springs. “He was really involved in our life,” Turki says.

Just as they affected the lives of so many others, the 9/11 attacks disrupted the relative tranquility al-Turki’s children had enjoyed while growing up in Colorado. “As kids, you don’t understand what discrimination is,” Turki says. “You interact with kids your age; they don’t have agendas. That’s why it was difficult in 2001 to understand the hatred. We were very shocked and scared, like any Americans.” One day, Turki says, a man entered their school and started screaming at Muslim children; another time, one of al-Turki’s daughters recalls walking through a Home Depot parking lot with her mother when a hostile man approached them and attempted to pull her mother’s veil from her face.

All of al-Turki’s children remember their father giving them the same advice for how to handle those types of situations; he explained that many people only understood what seemed to be an increasingly singular stereotype of Muslims. For every group of people there are people who are misrepresented, al-Turki told his kids. Prove them wrong and do good.

In addition to completing his schoolwork and raising his family, al-Turki started a publishing business, Al Basheer Publications & Translations, which was based in Aurora and primarily printed Islamic texts in English. In a fortuitous business move, al-Turki acquired the publishing rights to a set of sermons by American-born cleric Anwar al-Awlaki titled The Lives of the Prophets. Al-Turki released them as CDs and cut checks to al-Awlaki for his share of the royalties.

The al-Awlaki sermons—retellings of the classic tales of Islam—became popular among English-speaking Muslims. At the time, it wouldn’t have been uncommon to find the box sets strewn on the passenger seats of cars or living room coffee tables in the United States, or even in Canada or the United Kingdom. Indeed, in his exhaustive book on al-Awlaki, Objective Troy: A Terrorist, a President, and the Rise of the Drone, New York Times reporter Scott Shane writes: “Al Basheer was a successful enterprise for some years, and Awlaki was its unrivaled star.

Leading up to 9/11, and for several years after, al-Awlaki was considered a moderate. He’d attended Colorado State University in the 1990s and spent time in Denver, preaching on and off at the Denver Islamic Society. Al-Awlaki publicly condemned the 9/11 attacks and al-Qaida, and in early 2002, he was asked to speak in Washington, D.C., at a luncheon lecture series at the Department of Defense. His thinking did eventually shift, though; according to Shane, al-Awlaki showed his first signs of radicalization around 2003. Al-Turki’s business relationship with the controversial cleric would not go unnoticed by the U.S. government.

When, exactly, and why al-Turki first landed on the government’s radar is unclear. There was the visit from the INS agent after 9/11; however, according to a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Significant Incident report dated June 1, 2005, the federal government was looking at al-Turki years earlier. As a line in the report says, “The Denver FBI [Joint Terrorism Task Force] opened an investigation into Al-Turki based upon a national security concern, which has been in progress since 1997.”

Regardless of whatever interest the government had in al-Turki from a national security perspective, no formal charges had materialized; nevertheless, by 2005 the government had developed a case against him focused on immigration violations. The case pertained to al-Turki harboring his housekeeper—identified as “Z.A.” in publicly filed court documents—who was living in the country on an expired visa. There was also, according to court documents, the possibility of criminal tax violations related to al-Turki’s publishing business.

On Wednesday, February 9, 2005, al-Turki and his attorney John Richilano agreed to voluntarily attend a meeting with U.S. Attorney Brenda Taylor to discuss the immigration case and the possibility of a plea deal. The gathering had been mutually agreed upon and was also attended by FBI agent Jon Bibik and Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent Mike Riebau.

Riebau, who retired in 2007, says he first became involved with al-Turki’s case via a late-career assignment to the Denver-based terrorism task force. He’d spent most of his professional life working immigration and drug cases for INS. That agency, however, disbanded in 2003 as part of a post-9/11 government reorganization, a shift that created the Department of Homeland Security. When he joined the task force, Riebau says he learned the government had been looking at al-Turki as a national security case. “Those types of cases languish,” he says. “People work ’em a little bit, and then they don’t work ’em.”

Riebau says he tried to bring a fresh perspective to the investigation, from an immigration point of view. He also says al-Turki’s connection to al-Awlaki—who in 2011, in Yemen, became the first U.S. citizen to be targeted and killed by an American drone strike—wasn’t the only reason he was a target. “That doesn’t make him a bad person,” Riebau says. There were other things, he says, “behind the curtain.” Riebau would not elaborate on what he knows about al-Turki, and many of the documents related to the federal investigation into al-Turki remain classified.

Meanwhile, federal law enforcement agents had already shown they were serious about the immigration case: Three months before the meeting with the U.S. attorney, in November 2004, immigration officials raided al-Turki’s home, pointing guns at his wife’s head in front of his children and taking Z.A. into custody. “I’ve never seen something like that,” Turki says. “They wanted to put fear in us.”

According to a three-page summary Richilano typed up afterward, Taylor opened the February 9 meeting by providing an overview of the immigration and tax investigation into al-Turki. Bibik and Riebau also spoke; Riebau, whom Richilano described as aggressive and hostile, said the government would not give up pursuing al-Turki unless there was a deal. Taylor suggested a guilty plea to one count of harboring with a stipulation to a probation sentence and departure from the country. No one mentioned terrorism, according to Richilano’s written record of the meeting.

Two weeks later, Taylor sent a memo to Richilano laying out the formal terms of a potential deal. The requirements were for al-Turki to plead guilty to “harboring an alien” for the purpose of private financial gain (the allegation was that al-Turki was not sufficiently compensating Z.A. for her work at his house), to pay the victim full restitution, to be debriefed by agents, and to be deported. In exchange, the government was willing to “(1) make a binding recommendation Al-Turki receive no jail time (2) not pursue charges against his wife for the same charge, and (3) terminate all other investigations related to harboring other illegal aliens, forced labor violations, and tax violations.” In other words: Plead guilty, talk to an agent, and go back to Saudi Arabia.

Taylor gave al-Turki about two weeks to entertain the offer, but he wasn’t interested in a deal. “Homaidan and Sarah are both very emotional about this and understandably so,” Richilano wrote in his memo. “[H]is reaction is never give in, and I see no reason to take the offer seriously. Homaidan wishes as much time as possible to continue working toward his degree, distractions of being indicted notwithstanding.”

Given the gift of hindsight, al-Turki might’ve considered the offer more seriously. (Richilano and Dan Recht, an attorney who also represented al-Turki at the time, declined to comment for this article.) As federal and state prosecutors continued to pursue al-Turki, the case against him evolved from the charges Taylor had outlined. During the months before and after the meeting, FBI agents conducted a series of interviews with Z.A., during which she recounted several disturbing details and incidents.

The first interview took place in November 2004, and there was a series of approximately 12 additional FBI interviews in the months thereafter. Z.A., who is listed in court records as having been around 20 years old at the time of the interviews (though official documents ascribe a number of different ages to her), recounted numerous occasions when she said al-Turki sexually assaulted her. Z.A. described one incident in which she said al-Turki attempted to enter the bathroom while she was showering. She also recounted to FBI agents other more invasive assaults, including one in which she said al-Turki entered her room and forcibly placed his fingers inside her vagina and another in which he masturbated on her breasts. In all, Z.A. described more than a dozen such incidents to law enforcement agents.

In June 2005, al-Turki was charged with 12 counts of sexual assault, kidnapping, theft, and criminal extortion in state court. During a 10-day trial in the summer of 2006, prosecutors alleged al-Turki and Khonaizan kept Z.A. as a virtual slave. According to an Associated Press report, the government argued the woman “spent four years cooking and cleaning for the al-Turki family while sleeping on a mattress on the basement floor and getting paid less than $2 a day. Al-Turki was accused of hiding her passport.” (Al-Turki denied all of Z.A.’s allegations.) The jury found him guilty of unlawful sexual contact and false imprisonment, lesser offenses. He was also convicted on the theft and extortion charges. (Al-Turki was ordered to pay Z.A. about $60,000 in restitution.) When the judge read the verdict, many of al-Turki’s supporters wept; at least one person had to be removed from the courtroom.

Among the defense, there was confusion regarding what prison sentence would correspond to al-Turki’s convictions. According to court transcripts, the defense seemed to think its client had been convicted of mostly misdemeanors, telling the judge “as the court is aware, the guilty verdicts are on misdemeanors for the first 14—15 counts; no, 14 counts, and then the extortion is a Class 4, and the theft is—I believe it’s a Class 3.” Prosecutor Ann Tomsic of the 18th Judicial District corrected the defense. She explained that because the jury found the charges included “applications of threat, force, or intimidation,” the unlawful sexual contact charges were in fact Class 4 felonies.

That misunderstanding was consequential. The felony charges corresponded to a minimum sentence that would have no determinate end date, meaning the only mechanism al-Turki would have to be released from prison would be a favorable ruling from a parole board.

Waymart, Pennsylvania, a blue-collar town of about 1,300 people, sits 145 miles north of Philadelphia. There are more diners serving comfort food and bottomless cups of weak coffee than stoplights in town. The only grocery store is a place called Ray’s Supermarket, which closes at 9 p.m. The nearest town of any real significance is Scranton, about 30 minutes southwest on U.S. 6. Former Vice President Joe Biden used to tout his small-town cred on the campaign trail by referring to himself as the “scrappy kid from Scranton.” But if you live in Waymart, Scranton’s the big city.

Al-Turki is currently incarcerated at the United States Penitentiary, Canaan, a high-security federal penitentiary on the outskirts of Waymart. It’s his most recent stop after a series of transfers; previously, he was held at a high-security prison in East Texas nicknamed “Bloody Beaumont.” Before Beaumont, he spent seven years, at two separate facilities, in the Colorado state system. In all, it was 12 years ago this month that a judge sentenced al-Turki to 28 years to life. (A judge later reduced the sentence to eight years to life in accordance with statutory requirements of the sentencing law.)

At his August 31, 2006, sentencing hearing, al-Turki himself claimed he’d been under investigation as a suspected terrorist since 1995. He suggested that the federal government’s lack of success in building a terrorism case against him over the previous decade had been the motivation behind this prosecution and that the FBI had persuaded the housekeeper, who had initially denied any sexual abuse, to accuse him of the behavior for which he was ultimately convicted. A 2006 Associated Press story covering the sentencing quoted al-Turki as saying, “I am not a terrorist and I don’t advocate terrorism.”

At sentencing, al-Turki also claimed anti-Muslim sentiment had tainted the trial. According to the AP report, al-Turki told the judge, “I was convicted on fear and emotion, not facts. I want a fair trial where my religion and where I come from is not [the basis for] a conviction.” Al-Turki claimed in the report that he treated his housekeeper “the same way an observant Muslim family would treat

a daughter.”

Now, after more than a decade in prison, al-Turki still adheres closely to his culture and religion. He passes the hours by praying five times daily, an obligatory ritual considered the second of the five pillars of Islam. Over the years, al-Turki has filed multiple grievances against the Colorado Department of Corrections (DOC) concerning his religious practice, including a 2008 complaint that alleged a corrections officer disrupted a sacrosanct morning meal during the holy month of Ramadan by yelling and using profane language toward Muslims in the chow hall. A DOC employee responded to the grievance two months later by stating that the matter had been “investigated and addressed on an administrative level.”

That al-Turki eventually left Colorado and ended up where he is today in Waymart is unusual. It’s uncommon for a prisoner convicted on state charges and serving a sentence in a state institution to make the jump to the federal system. For al-Turki, that leap occurred in spring 2013 in the wake of one of the most extraordinary events ever to befall the DOC. On the evening of March 19, the DOC’s then executive director, Tom Clements, heard a knock on his front door. When he answered, he found a man dressed in a Domino’s pizza delivery uniform standing in the cool spring night. Without saying a word, the man shot Clements to death.

The following day, Fox31 Denver ran a story with the headline: “Sources: Clements murder investigation will look at Saudi prisoner connection.” The piece cited an unnamed source familiar with the investigation as having said “the al-Turki connection right now is the main working theory behind the Clements death.”

The El Paso County Sheriff’s Office, which had jurisdiction over the homicide, led the manhunt for Clements’ killer. Police dogs sniffed the woods near Clements’ home in Monument, and investigators combed his cell phone records for clues. Meanwhile, within hours of the killing, marked cruisers had parked outside the homes of lawyers and federal investigators who’d been involved with al-Turki’s case—and those who’d worked other sensitive cases—over the years, a precautionary measure taken for security purposes. As far-fetched as it might’ve sounded—that a man locked in a cell on the Eastern Plains could have orchestrated a hit on a high-ranking state employee—there was a thread that caused the sheriff’s office to initially consider al-Turki as a suspect.

Eight days before he was killed, Clements penned a letter to al-Turki. The note concerned a prisoner transfer request that had been made on al-Turki’s behalf about a year earlier; al-Turki wished to serve the remainder of his sentence in his home country. High-powered Denver lawyers Hal Haddon and former U.S. Attorney Henry Solano, who’d been hired to handle the transfer application, filed the request with the governor’s office, which kicked the application over to Clements for review. After several months, Clements informed al-Turki of his final decision: In a letter dated March 11, 2013, he denied the request.

One theory El Paso investigators were considering suggested al-Turki had somehow marked Clements for death in retaliation against the transfer denial. In the 48 hours after Clements was shot, the El Paso office made swift progress. Their search would eventually lead them to a man named Evan Ebel, who was affiliated with a white supremacist organization known as the 211 Crew, which exists both inside and beyond the prison system. A clerical error had led to Ebel being mistakenly paroled four years early. What El Paso investigators learned was that a short time after his release in January 2013, Ebel had murdered a 27-year-old Domino’s employee, Nathan Leon, and then used Leon’s uniform as a disguise when he approached and killed Clements. Two days after Clements’ murder, authorities found Ebel in Texas. Members of the Texas Rangers killed him in a gunfight on the side of a highway outside Decatur, a small city northwest of Dallas.

Following the Ebel shootout, media reports continued to cite al-Turki as a person of interest; his lawyers at the time denied that he had any involvement in the murder. Nevertheless, because of the accusations and the high-profile nature of the crime, al-Turki was moved to solitary confinement for his own safety and eventually transferred to a federal prison in Texas. At a regularly scheduled parole hearing eight months after the Clements murder, 18th Judicial District prosecutor Tomsic noted the possible al-Turki–Clements connection, citing it as a reason the judge should deny parole. According to an AP news report from the hearing, Tomsic argued that “if al-Turki leaves the country, authorities would not be able to bring him back if investigators later link him to the shooting death of Tom Clements.”

Recently, I spoke with three sources involved with the Clements investigation, including the head of the El Paso Sheriff’s Office at the time, Terry Maketa. All three sources confirmed that although al-Turki was looked at initially, investigators never found anything connecting him to Ebel. “We followed the evidence, and our evidence never steered toward him,” Maketa says. “His name really faded off quickly.”

According to retired El Paso detective Mark Pfoff, who specializes in analyzing cell phone records and worked the Clements case in that capacity, al-Turki did appear to have a connection to the 211 Crew; Pfoff said records indicated al-Turki was paying a gang member for security inside the prison, a practice that is not out of the ordinary. But, Pfoff told me, officials never found a link between al-Turki and Ebel or others who might’ve been involved with the Clements murder. Like Maketa, Pfoff said the evidence led elsewhere.

A third source, who would speak only on the condition of anonymity, confirmed the assessments of Maketa and Pfoff and notes that investigators could have been more careful about applying the logic of one particular inmate being motivated to assassinate the head of the DOC. “You have to realize,” the source says, “so are the other 30,000 inmates in Colorado.” What’s more, Pfoff says some in the El Paso department believed members of the Denver FBI were hanging onto the al-Turki theory past the point at which it made sense. “A lot of us were feeling this al-Turki thing wasn’t panning out,” Pfoff says. “When we heard the whole thing got out [in the media], we felt like we were kind of being pushed.”

The Clements case remains officially open to this day. This spring, on the five-year anniversary of the murder, the current head of the El Paso Sheriff’s Office, Bill Elder, told the Denver Post, “They’ve looked at everything and anything. To date [they] have not turned over any evidence that disproves that Evan Ebel acted alone.”

Once the high alert of the Clements murder and the disruption of al-Turki’s move to a federal prison had subsided, Denver lawyer Faisal Salahuddin filed a civil defamation suit dated March 12, 2015, on al-Turki’s behalf against members of the Arapahoe County District Attorney’s office and members of the Denver FBI office. The lawsuit deals in part with al-Turki having been cited in the media as connected to the Clements killing.

However, the lawsuit argues more consequential acts took place before Clements denied al-Turki’s prisoner transfer request. “Between November 30, 2012 and the present,” the 2015 suit reads, “Defendants abused their positions of authority as employees of State and Federal agencies by unfairly, unjustly, and maliciously defaming and stigmatizing Plaintiff by inventing and disseminating false allegations that Plaintiff is a terrorist, is associated with terrorists, and/or poses a national security concern.”

A judge allowed the lawsuit to proceed, and for more than a year, Salahuddin and lawyers for the defendants engaged in a battle over what information, including portions of classified documents, should have to be produced for discovery. Even so, much of what has been turned over to al-Turki’s attorneys remains under protective order, which means it can only be viewed by the judge and certain members of each legal team.

Documents and email correspondence entered into the public record as part of the lawsuit, however, show that Clements had initially granted al-Turki’s transfer request, and, according to Salahuddin, changed his mind only after sitting through a meeting at which the FBI delivered a classified PowerPoint presentation that, Salahuddin claims, falsely and knowingly smeared his client as a terrorist.

This spring, in a blow to al-Turki’s continued legal fight, a judge dismissed the case. Salahuddin has since appealed the case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit.

On the morning of January 16, 2013, two months before he died, Clements reached for his iPhone and typed a short email to Jack Finlaw, Governor John Hickenlooper’s chief legal counsel at the time. Finlaw had been corresponding with al-Turki’s attorney Hal Haddon about the progress of al-Turki’s transfer request, and Clements forwarded him an email with an update on the paperwork. “Jack, I signed the transfer letter Monday Morning. As you can see from Paul’s message it has not gone out yet due to instruction receives [sic] from DOJ.”

In this case, the mechanism to transfer a prisoner from the United States to his home country is a three-step process, pursuant to the Inter-American Convention on Serving Criminal Sentences Abroad. First, if the offender in question is a state prisoner, which al-Turki was at the time, he is required to get signoff at the state level. Then, authorities at the DOJ, which includes the FBI, review the request; DOJ guidelines state that “the Department of Justice frequently approves state cases unless a compelling federal interest exists or a treaty requirement has not been satisfied.” Lastly, the receiving country has to agree to the transfer. Al-Turki’s packet appears to have gotten hung up in the handoff between steps one and two.

The state office tasked with that handoff, according to DOC administrative regulations, is known as Offender Services. At the time, Paul Hollenbeck—the Paul referenced in Clements’ email to Finlaw—was the department’s associate director. In an email, Hollenbeck wrote that after he received Clements’ signed approval letter, he contacted the DOJ and spoke with an attorney who informed him that “she had been contacted by the Denver FBI office regarding information they wished to present in opposition to the request.”

What happened next sits at the crux of the lawsuit Salahuddin filed. In late January or early February, at least two members of the Denver FBI delivered a briefing to state officials, including Clements, about al-Turki. In that meeting, the officials gave a PowerPoint presentation containing classified information related to al-Turki; Salahuddin said the majority of the presentation dealt with terrorism connections—allegations that have never amounted to charges against al-Turki.

An FBI public affairs contact in Washington, D.C., said she could not respond to a request for comment. She said any questions regarding a civil suit should be directed to the Department of Justice, which represents the FBI in the case. The DOJ also declined to comment on the lawsuit.

I requested a copy of the PowerPoint presentation from the FBI under the Freedom of Information Act. The government’s response stated that my inquiry had been denied because, “You have requested records on one or more third party individuals…. The mere acknowledgement of the existence of FBI records on third party individuals could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” In other words, the correspondence stated that the FBI could neither confirm nor deny the existence of the records I’d requested.

Publicly filed court documents, however, not only confirm that the presentation exists, but also that it contained at least one falsehood. One of the slides, more than half of which is redacted, indicates that a book titled Blast Effects on Buildings was sent from an unknown origin to al-Turki’s publishing company, Al Basheer. But portions of a previously classified FBI report dated February 1, 2005, detail a mix-up with the book, which was shipped from London and entered the United States through a port in Newark, New Jersey. The report states there were no suspicious items connected to terrorism bound for Al Basheer. A separate shipment on the same pallet did include hardbound books entitled Blast Effects on Buildings, but those books were headed to the American Society of Civil Engineers in Reston, Virginia.

“As Exhibits 3 and 4 demonstrate,” Salahuddin wrote in a court filing, “even the small shreds of discovery that have been produced demonstrate Mr. Al-Turki’s fundamental claim is true: the Federal Defendants misrepresented the documents in the FBI’s possession to the Colorado official in charge of deciding on Mr. Al-Turki’s treaty transfer application, fabricating claims that Mr. Al-Turki supported terrorism in order to cause Colorado to change Mr. Al-Turki’s legal status from that of a prisoner with a treaty transfer application approved at the state level to that of a prisoner with a denied treaty transfer application.”

Multiple DOJ attorneys in Washington, D.C., representing the FBI defendants in this case fought against disclosing additional classified information related to al-Turki based on the state secrets privilege. (This privilege is established via case law and permits the government to not disclose information that could harm national security interests.) Had the litigation continued at the District Court level, the defendants—members of the FBI—would have needed to produce Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ signoff to fully assert the privilege.

Salahuddin declined to specifically discuss the rest of the PowerPoint presentation, which he has seen in redacted form. But he did suggest an analogy: “Let’s put it this way,” he says. “If my guy was a German, they put a picture of a swastika in the PowerPoint knowing full well he wasn’t a Nazi.” He added: “Have you ever played the game six degrees of Kevin Bacon? Everyone is six degrees from Kevin Bacon.”

In dismissing the case earlier this year, U.S. District Court Judge Robert E. Blackburn did not question the facts produced thus far; instead, he ruled on a legal matter known as the “plus factor.” The plus factor “requires the plaintiff to allege that a constitutionally protected liberty or property interest was impaired as a result of the alleged government defamation.” Blackburn ruled that the reversal of the transfer application did not meet that requirement. Salahuddin, however, argues al-Turki’s protected liberty interest is not in the transfer denial but rather in his constitutionally protected name and reputation—and that’s what was impaired by the government’s alleged defamation.

Following Blackburn’s ruling this spring, the 18th Judicial District released a statement, which included this quote from Tomsic: “Homaidan Al-Turki has had the keys to his own cell since 2011; it is his continued refusal to participate in the required sex-offender treatment that prevents his parole and deportation to Saudi Arabia. Mr. Al-Turki needs to take responsibility for own [sic] behavior and incarceration.” According to his attorneys, al-Turki has not taken the required sex-offender treatment because it would require him to admit guilt, which he refuses to do.

In response to an inquiry for this story, the 18th Judicial District sent me the following statement via email: “The case was dismissed, and the plaintiff is now pursuing an appeal. We believe it is more appropriate to let the appellate process play out than to make any public statement at this point in time.” At press time, the 10th Circuit court had not ruled on the appeal.

Twelve years after al-Turki was sent to prison, he continues to assert his innocence—and evidence not presented at the 2006 trial may bolster that claim. Hired to conduct al-Turki’s post-conviction process, Boulder attorney David Wymore began digging into the case a few years ago. Wymore says he found inconsistencies in Z.A.’s FBI interviews that were never investigated nor raised by al-Turki’s attorneys, most notably that Z.A. admitted first to having sexual contact with al-Turki’s son, Turki. According to an affidavit signed by Turki in 2013, he claimed Z.A. was the one who initiated the contact, but in her interviews, Z.A alleged the teen had come onto her. (According to Wymore, Z.A. has left the United States, and he believes she is living in either Indonesia or China; she could not be reached for comment.)

In his 355-page motion for release, Wymore writes, “In order to protect that witness, Z.A., from inquiry into circumstances which any reasonable person would find highly suspect, the government agents completely ignored her assertions of sexual contact with an 11-[to-]15-year-old, Mr. Al-Turki’s son, T.A.T. They also ignored, or did not believe, the highly unlikely scenario of T.A.T. being an aggressive sexual predator as claimed by Z.A.—which, if true, left him free to prey upon his siblings and all other women and children in Colorado and elsewhere.” Wymore adds, “Had anybody bothered to ask the child about any of this, they would have learned Turki was the subject of Z.A.’s advances.”

Wymore’s motion—which also alleges numerous instances of ineffective assistance of counsel stemming from how al-Turki’s previous attorneys investigated the case and approached his trial—is still pending. “If someone can bring a piece of evidence to the contrary,” Wymore said of the claims in his appeal, “I’d be willing to reverse my opinion.”

Al-Turki, who is now 49 years old, has not spoken on the record to an American media outlet since his conviction. (He did talk to an Arabic-language TV station in 2007, saying, “I swear by the name of God what happened in the court was a farce and not a fair trial; it was the trial of the Islamic veil. There was no exposure, there was no hard evidence, there was no hard evidence.”) Through his attorneys, al-Turki agreed to an interview for this article, but the Federal Bureau of Prisons denied multiple requests I filed to speak with him in person at USP Canaan. The prison bureau also refused to allow al-Turki to respond to a list of questions submitted in writing via mail. According to correspondence I received signed by USP Canaan’s warden, both to my initial request and a subsequent appeal, the interview was denied for security purposes. “After careful consideration I must decline your request for an interview based on maintaining security and good order of the institution,” warden Juan Baltazar wrote to me. The public information officer handling the request declined to elaborate on the nature of those concerns.

When I contacted the Saudi Arabian embassy (the Saudi government offered to pay al-Turki’s bail in 2005) in Washington, D.C., for comment regarding al-Turki’s case, I reached a man named Fahed al-Rawaf, an official at the embassy who had previously spoken in court on al-Turki’s behalf. Al-Rawaf, however, declined to speak about the case and instead referred me to Wymore.

During one of our conversations, Salahuddin told me that when he’d first read news stories about al-Turki years ago, before he represented him, he thought some of the allegations seemed plausible. His point of view shifted when he joined the case and had a chance to investigate and review evidence. “Everything I’ve seen in four years has been beneficial to us,” Salahuddin says. That includes, he says, the infamous 28 pages.

For years, the 28 pages that had been redacted from the final 9/11 Commission Report were touted as something of a smoking gun that would detail the extent to which Saudi Arabia played a role in the attack on the United States. In 2016, following an extensive government review, President Barack Obama’s administration finally declassified that portion of the report. Al-Turki’s name is not in the 28 pages; it does, however, show up in a few supplemental 9/11 commissioner notes and in a joint commission-FBI report, where his name appears near the bottom of a list of 44 persons of interest. In the 9/11 commissioner notes, he’s detailed as “a Saudi student living in Colorado, whose education is being funded by the Saudi Government.” The notes also state, “He was in contact with an individual in Germany in 2001, who was also in contact with one of the hijackers. His uncle is a prominent Saudi Cleric, and he also has other ties to the Saudi Royal Family.”

When I asked Salahuddin about the German connection mentioned in the commission notes, he told me it was a phone call to al-Turki’s publishing company and said the call went unanswered.

Salahuddin said the disclosures confirm what he and others—al-Turki’s trial lawyers made the same argument 12 years ago—have been saying all along: The government took a look at al-Turki but didn’t find anything that stuck. “This is a political prosecution against him,” Salahuddin said. “That’s what it always was.

“The truth,” he added, “is on our side.”