The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Strange Land

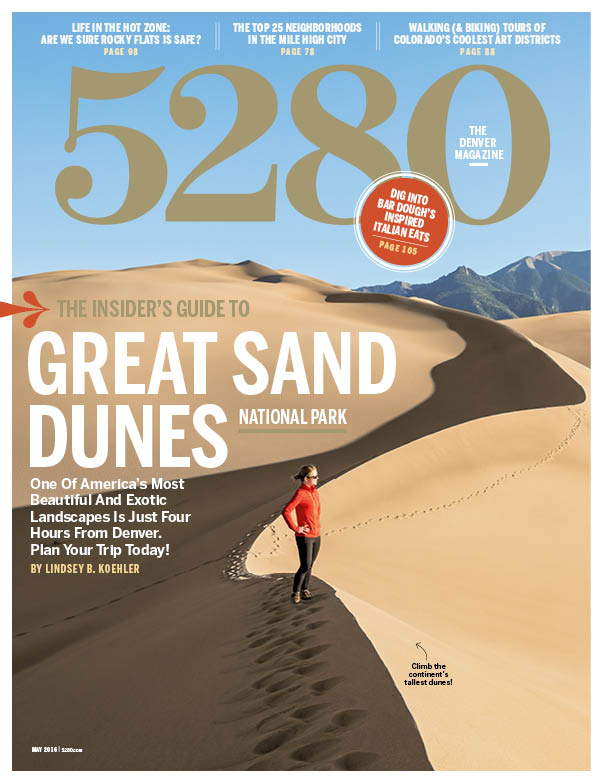

Mother Nature whipped up a must-see geological oddity in the Centennial State’s most enigmatic valley.

Anecdotal evidence suggests the most common refrain among first-time visitors to Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve is, “This place is so weird.” The funny thing about that sentiment is it accurately describes not only the 30-square-mile field of dunes but also the isolated, underdeveloped San Luis Valley that surrounds it.

The valley’s violent birth—which began 35 million years ago when volcanic eruptions created the San Juan Mountains and subsided 16 million years later when the Rio Grande Rift shifted to expose a valley floor and produce the Sangre de Cristo Range—was just the first hint that Colorado’s largest mountain vale would exhibit a flair for the dramatic. The San Juans, to the west, would end up being the largest range in the U.S. Rockies. The Sangre de Cristo Range, to the east, would become famous for its red alpenglow and its 14,000-foot peaks. And the dunes, estimated to have begun forming at the foot of the Sangre de Cristos about 440,000 years ago, would turn out to be 750 feet tall, making them the highest sand dunes on the continent.

But these features—freakish as they are—are nearly equaled in bizarreness by the area’s cultural portfolio. To wit: The San Luis Valley is known as a paranormal hot spot, a place where believers from around the globe flock to privately owned UFO watchtowers. Crestone, located north of the national park, is a stronghold of spirituality and serves as home base for dozens of religious organizations. Also thrown into the psychosocial soup are the facts that a high percentage of area residents are Hispanic; a large settlement of Amish call Monte Vista home; agriculture remains a vital part of the local economy; the solar energy industry moved in and began harnessing alpine-desert rays in 2007; and, if that weren’t enough, the valley hosts an 80-acre reptile park.

All of which, of course, makes the nearly four-hour trip from Denver to the entrance of Great Sand Dunes National Park completely worth it in any year. But because 2016 marks the 100-year anniversary of the National Park Service, planning a summertime visit to Colorado’s newest national park (it was established in 2004) seems extraordinarily appropriate. There is a catch, though. If you don’t know how to do the dunes right, you could find yourself feeling a little underwhelmed—Is this it? What do we do now? How do we get to the lodge? Where can we grab a beer?—after the initial bewilderment wears off. Fortunately, we’re here to make sure you know everything you need to before making your way to what has to be one of the country’s most unique national parks.

Making The Dunes

Natural forces, swirling winds, and flowing streams have all played vital roles.

After explosive volcanic activity created the San Juans and plate tectonics pushed up the jagged Sangre de Cristos, sediment from both ranges as well as water from mountain streams and rivers converged in the basin below. A huge lake, today called Lake Alamosa, is thought to have covered a large swath of the San Luis Valley before accumulating sediment caused it to empty. Smaller lakes came and went over the years, leaving behind an area of wetlands and a large area of loose sand called a sand sheet. Prevailing southwesterly winds picked up that loose sand and blew it into a depressed bend in the Sangre de Cristos.

Storm winds, which gusted down from the Sangre de Cristos into the valley, caused the deposited sand to blow back on itself, forcing the dunes to grow vertically. Two mountain streams—Medano and Sand creeks—ensnared grains of sand from the Sangre de Cristo side of the dune field and carried them to the valley side. There, the water disappeared into the sand sheet, the grains dried, and the predominant winds re-deposited them back on the mountainside. Today, the same recycling processes maintain the dunes, which, for now, are not growing or shrinking. Of course, that doesn’t mean the dunes aren’t changing. “The wind is an artist,” says Eric Valencia, a former Great Sand Dunes park ranger. “It renews the dunes every day.”

(Read more about the creation of the Great Sand Dunes)

Two-Faced

Take time to get to know the park and the preserve, Great Sand Dunes’ charming yet split personalities.

If you look at a map of Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, you’ll notice that a thin boundary line bisects the chart. In the western section—the designated national park—lies the star attraction: the dune field. It’s the can’t-look-away feature visitors travel here to see. And who can blame them? The dunes are sculpture art of the highest order. Each day, Mother Nature ever so slightly tweaks the angles and changes the way light and shadow dance on the sand. It’s an otherworldly spectacle, especially at sunrise and sunset, when most guests make the (poor) decision to head home. But with everyone’s attention trained on these easily accessible mounds of sand, the eastern half of the map—the preserve—can get overlooked.

More than 41,000 acres of raw Sangre de Cristo Range wilderness tuck into the mountainsides adjacent to the dune field. Here, the earth is still sandy, but rocky outcroppings soar overhead; forests of aspen and fir sway in the breeze; subalpine meadows host mule deer, elk, and black bear; and mountain lakes and streams teem with trout. Yes, the preserve is as lovely as any number of areas that can call themselves national parks; however, unlike, say, Rocky Mountain National Park, there is little infrastructure and few easy ways to access the grandeur. From inside Great Sand Dunes’ boundaries, the two main entries into the preserve’s backcountry are the Mosca Pass Trail (the trailhead is near the visitors center) and the Medano Pass Primitive Road (for which you’ll need a high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle and a portable air compressor to deflate and inflate your tires as necessary).

The mistake many visitors make is traveling from far away to get to the park, then spending a scorchingly hot hour or two on the dunes in the middle of the day and leaving without having experienced the dune field during off hours or seeing the preserve at all. One could blame the quick turn to leave on the scarcity of king-size beds—the park does not have a lodge, and nearby hotel rooms are in short supply—but those adventurous enough to camp are justly rewarded. Jaw-dropping sunsets. Unobscured stargazing. The precious silence of isolation. It’s not that you can’t enjoy Great Sand Dunes during a short daytrip; you can. But to truly appreciate both the park and the preserve—to learn their quirks, to cherish their nuances, to understand what makes each special—means investing a little more time and effort.

Playing by the Rules

What you can—and can’t—do in Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve.

In the park you…

– Can camp on the sand dunes, with a free permit obtained in person at the visitors center, outside of the day-use area; only 10 permits are allowed each night

– Can camp in Piñon Flats Campground, with a reservation obtained online at recreation.gov from May 4 to September 18

– Can hike with your dog in the day-use area so long as he is leashed

– Can sandboard and sand sled on the dunes, but only in the day-use area

– Can ride horses, mules, burros, or llamas in designated areas

– Can gather piñon nuts, gooseberries, mushrooms, currants, raspberries, and strawberries in limited quantities

– Can have a fire in designated areas in fire grates

– Can bury human waste in the dune field so long as it’s covered by six inches of sand (toilet paper must be packed out)

– Can’t camp overnight with your dog

– Can’t fly a drone

– Can’t camp for longer than 14 consecutive days

– Can’t hunt

– Can’t have a fire in the dune field

– Can’t use glass containers

– Can’t leave food, garbage, or toiletries unattended; they must be stored in a vehicle or bear box or suspended 10 feet above the ground

In the preserve you…

– Can camp in wilderness areas so long as you’re 200 feet from a trail, 300 feet from a lake, below timberline, and not in a Krummholz tree zone (in these areas, stunted trees struggle to grow on exposed mountaintops)

– Can camp along Medano Pass Primitive Road, but only in designated sites (which are free and first come, first served; no permit necessary)

– Can camp overnight with your dog

– Can have a fire in designated wilderness, but only in existing fire rings below treeline

– Can have a fire along Medano Pass Primitive Road, but only in metal fire grates or existing fire rings

– Can hunt

– Can ride horses, mules, burros, or llamas

– Can collect dead wood already on the ground that is less than four inches in diameter for campfires

– Can bury human waste in wilderness areas so long as it’s covered by six inches of soil and 100 feet from water (toilet paper must be packed out)

– Can gather piñon nuts, gooseberries, mushrooms, currants, raspberries, and strawberries in limited quantities

– Can’t fly a drone

– Can’t camp for longer than 14 consecutive days

– Can’t leave food, garbage, or toiletries unattended; they must be stored in a vehicle or bear box or suspended 10 feet above the ground

Footprints In The Sand

Thirty square miles of terrain to explore—and exactly zero trails to follow.

Those who subscribe to the romantic notion of forging one’s own trail will surely find Great Sand Dunes’ undulating, mostly untrammeled dune field refreshing. Unlike many other state and national parks, Great Sand Dunes offers minimal signage and, among the dunes, not a single permanent footpath. Most tourists access the dune field from the main parking lot just past the visitors center. From there, you can cross braided Medano Creek and a flat area of packed sand before weaving your way up to the summit of High Dune, a 699-foot-tall sand pile that is the highest peak along the first ridge and the most visited spot in the park. The hike takes most people about two hours round trip. From the top of High Dune, you can see Star Dune—a 755-foot behemoth—to the northwest. Getting from the parking lot to Star Dune and back generally requires a five-hour hike, during which you’ll definitely have some company.

But if you want your footprints to be the only ones you see, drive past the main parking area to Point Of No Return, a small parking area where you can take a trail (through the Sand Pit parking area) into the dune field. Here, Medano Creek is devoid of waders, and there are far fewer hikers. The feeling you are lost in the Sahara Desert is tempered only by the fact that the Sangre de Cristos rise, lush and green, to the east. This area of the dune field is particularly magical as the sun goes to bed over the San Juans. Our advice? Start a summertime hike around 5:30 p.m., trek up and over the first ridge, and find a prime west-facing dune on which to watch the sunset. Do not forget your camera.

By the Numbers

150°

Temperature, in degrees Fahrenheit, the sand can reach on a sunny day

755

Height above the valley floor (which has an average elevation of 7,600 feet above sea level), in feet, of the park’s tallest dune

299,985

People who visited—and presumably hiked on—the dunes in 2015 (for comparison, Rocky Mountain National Park sees more than four million visitors each year)

Trip Tip: How to Hike in the Sand

1. Plot your climbs along the ridges of the dunes; sand tends to be softer on the faces.

2. Sand along the edges of vegetation—sunflowers, grasses, and scurfpea grow on the dunes—is usually firmer, which allows for easier hiking.

3. The dunes only see about 11 inches of precipitation annually, but July and August showers compress the sand, making the dunes much easier to ascend afterward.

Native Species

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve superintendent Lisa Carrico had never lived anywhere but national parks until she went off to college (her father worked for the National Park Service for more than three decades). As a kid, Carrico was immersed in landscapes most Americans simply hope to one day visit on vacation, and she always knew that the national parks were where she was supposed to be. Over the past 32 years, Carrico has worked at 10 parks, including Great Sand Dunes for the past four years. We spoke with the superintendent about what makes Great Sand Dunes distinctive, the importance of conservation, and (shhhh!) her favorite spot in the park.

5280: I hear there’s a unique story about your office at Great Sand Dunes?

Lisa Carrico: That’s true. My father was actually the superintendent of this park [it was a national monument in those days] for six years starting in 1969. I was 11. I went to middle and high school in Mosca, a town you’ll miss if you blink. Anyhow, my family lived in the superintendent’s quarters inside the park. Today, my office is located in what was then our living room. It’s a little weird.

There are probably very few people who know the park better than you—what makes it special?

Its diversity. The fact that there are 30 square miles of sand dunes nestled up against alpine peaks is amazing. We protect an area of land that goes from a high desert valley floor to 750-foot dunes to 14,000-foot mountains. All national parks are unique, but few have that kind of variability.

Why are national parks still important in 2016?

Parks are touchstones. It’s important for us to protect these places, but in doing so, we are also protecting people’s stories and memories. For example, people have been coming to the Great Sand Dunes for more than 10,000 years. When we think of national parks, we often think of Yosemite or Yellowstone National Park, but there are many less-well-known parks that preserve and represent the full stories of this nation.

The Great Sand Dunes visitors center offers a variety of ranger-led programs—which one is a can’t-miss?

The night sky program. I never tire of hearing people’s reactions to being able to actually see the Milky Way. Many of our guests come from urban areas where there’s light pollution; it’s so dark down here that you can see it with the naked eye.

What is your favorite spot in the park?

Anywhere along Medano Creek. Because of the surge flow, if you close your eyes it sounds like you’re at the beach.

What do you worry about when it comes to the future of Great Sand Dunes and other national parks?

Our mission is to conserve resources so they can be enjoyed by this generation and all future generations. There are not a lot of local threats to the Great Sand Dunes anymore, but I’m generally worried about climate change and population increases. I look at it from a global perspective, and I think about how we, as a relatively small park, can make a difference with regard to these very complex problems.

Who Needs Snow?

It’s our job as Coloradans to find the best tricks for careening down hills, no matter what they’re made of. Here, our insider tips for sliding on the sand.

- Leave your snowboard and your favorite Flying Saucer sled at home—they won’t slide on the sand. Ditto for cardboard.

- Rent a specially designed sandboard or sand sled from one of two retailers in the San Luis Valley. The closest to the dunes is Great Sand Dunes Oasis ($20 per day; greatdunes.com), a one-stop shop outside the park’s main entrance. The other is Kristi Mountain Sports in Alamosa ($18 per day; kristi

- mountainsports.com), about a 35-minute drive from the park. Both shops will give you wax.

- Plan to sled in the morning or later in the evening, when the sand is cooler.

- For a faster ride, wait for an afternoon rain shower; cold, wet sand speeds up the descent.

- Find slopes with a suitable gradient. Dune faces with a pitch of at least 20 degrees will facilitate your slide. Warning: There is such a thing as too steep; watch out for dunes that drop off abruptly.

15 Hours of Solitude

The pleasures of a hard-won—and completely isolated—campsite.

The half-mile jaunt from where I’d parked to where I entered the dune field had been downhill, so I was surprised when sweat began trickling down my back. I guess I shouldn’t have been: Walking in sand is difficult. Walking in sand while schlepping a 25-pound backpack is downright exhausting. I removed my hiking boots and splashed around in the cool waters of Medano Creek before considering the uphill hike in front of me. After strapping my boots to my pack, I set off bound and determined—and barefoot—to find the perfect away-from-the-crowds campsite.

I needn’t have worried about seeing other people. Choosing to begin my hike at 4:30 p.m. meant the sand would be cool to the touch, but it also meant dayhikers would be headed back to their cars. My solitude was further protected by the fact that it was a Thursday, which prompted a visitors center ranger to tell me I’d likely be the only person issued a permit to camp in the park’s backcountry that night.

After about 20 minutes of climbing, I began to understand why I was the only one looking to pitch a tent on the dunes: The hike was brutal. For every step forward, I slid two steps back. Twice I actually fell over, my balance thrown off by the incline, the earth giving way under my feet, and the weight I was carrying on my back. The ranger had explained camping was only allowed outside of the day-use area. To get to the backcountry, I needed to cover about 1.5 miles. “If you can still see the visitors center,” the ranger said, “you haven’t gone far enough.” I’m pretty sure I didn’t make it the full 1.5 miles before I simply had to put the pack down, but I found a lovely dip between two dunes in which to set up camp. From inside that deep depression, it felt like I’d been swallowed by the sand.

Normally when I go camping, a flickering campfire holds my attention after the sun departs. Worried I’d be bored without the hypnotic flames (fires are not permitted on the dunes), I brought a book to read by headlamp. The imported distraction was unnecessary. I found that all I wanted to do was lie on the sand, observe the dunes as day melted into night, and revel in the seclusion.

Trip Tip: Permit Roulette

To camp in the dune field, visitors must secure free permits in person in the visitors center. The park only issues 10 dune field permits—which are first come, first served—per night. During summer weekends, the dune field can fill to camping capacity. Our advice: Plan your trip midweek or arrive early Friday morning to secure a pass.

Camper’s Journal

6:25 p.m. I’m lying on the side of a west-facing dune. My tent is all set up. I had to put my backpack inside it to keep it from blowing away; apparently, tent stakes are not made for sand. I’m about to get up to find some granola when I see movement to my right. It’s hard to say for sure, but I think the dark spot on a nearby ridge is a coyote.

7:15 p.m. The wind is kicking up, and I can see why the dunes look different each day. Sand is blowing off the tops of the ridges, shaping and reshaping. It feels like sandpaper on my bare legs.

7:59 p.m. The dunes are magical at sunset. The contrast between light and shadow creates beautiful shapes and negative spaces.

9:45 p.m. The heavens are brilliant. I see two shooting stars before I go to sleep.

10:15 p.m. I’m in my sleeping bag when I hear a scratching noise coming from beneath my tent. Using a headlamp, I discover a Great Sand Dunes tiger beetle scavenging for food.

6:30 a.m. The sun rises over the Sangre de Cristos. I’m glad for the warmth. The temp is just 44 degrees as I walk through a field of sunflowers back toward my car.

Go With the Flow

Best experienced in May and June, Medano Creek serves as both a critical recycler of sand and the closest thing to a beach you’ll find in Colorado. When the spring snowmelt gushes from the Sangre de Cristos, Medano Creek swells from a thin ribbon to a wide stream that skirts the dune field. As it does, a rare phenomenon called surge flow develops. Medano Creek rolls across the sand in rhythmic waves, creating not only the sounds of the ocean but also the action of it—affording kids the opportunity to play in the “surf.” Here’s how it works.

Follow the Surge

1. Snowpack builds up in the Sangre de Cristos over the winter. When spring arrives, the snow begins to melt, and water enters Medano Creek.

2. The water in Medano Creek flows with a relatively high velocity due to the steep gradient of the Sangre de Cristos.

3. As the water moves downstream and into the dunes, it runs over a smooth yet constantly shifting streambed.

4. As water flows across the sand, small dams—or anti-dunes—arise on the creek bed, forming temporary reservoirs where water pools.

5. When the water pressure becomes too great, the dams fail, sending small waves downstream about every 20 seconds.

6. These waves—sometimes as high as one foot—easily take child-size inner tubes and their occupants for lazy-river-style rides.

Mind The Gaps

Three mountain passes—all located in the preserve—serve as recreational jumping-off points.

Music Pass, 11,380 feet

The highest of the preserve’s three gateways, Music Pass is also the least accessible. It’s a 21-mile hike from the closest parking lot (Point Of No Return) inside the park. But if you’re jonesing to see an alpine lake, you can drive 4.5 miles south of Westcliffe (on the east side of the Sangre de Cristo Range) on CO 69 and then proceed on four-wheel-drive roads to within 1.4 miles of the pass. You’ll park at the end of Music Pass Road and begin hiking toward the Music Pass trailhead. There are multiple lakes in the area, but the most scenic is arguably Lower Sand Creek Lake (a six-hour hike round trip). To reach this blue-green pool, you’ll summit the pass and then descend about 400 feet before reaching a junction. Bear right. When you come to another Y in the trail, go left. From here, a moderate 30-minute trek will leave you at the shores of the lower lake. (If you go right at the Y, a 1.2-mile hike drops you at Upper Sand Creek Lake.)

Medano Pass, 9,982 feet

As the only pass of the three you can drive over, Medano Pass is a must-see. You can access the top of the route using the Medano Pass Primitive Road—both from inside the park and from CO 69 via County Road 559 on the eastern side of the Sangre de Cristos. The road isn’t terribly difficult to traverse with four-wheel drive, but you’ll need to bring an air compressor because the road alternates between sandy and rocky. Being able to alter your tire pressure (lower for sand; higher for rocks) on the fly is a requirement. If you begin your drive from within the park, you’ll notice multiple designated campsites (they’re all first come, first served) along the primitive road; negotiate Medano Creek eight times; see the 1870s-era Herard homestead; and glimpse both high cliffs and grassy meadows. About 10.7 miles from the beginning of the unpaved road, you’ll encounter a well-marked spur road that leads to the trailhead for Medano Lake. The seven-mile round-trip hike to the lake is moderately challenging. But it’ll be worth it when you see the lake and 13,345-foot Mt. Herard.

Mosca Pass, 9,737 feet

Historically, Mosca Pass was the way to cross the Sangre de Cristos. Beginning in the 1870s, the path over Mosca Pass became a toll road, one that saw 40-or-so wagon crossings a day. Today, the pass is not a throughway. Although you can drive up to the pass from the east (see “The Back Door” at left) and park, the only way to enter the preserve is by foot. Alternatively, you can hop on the Mosca Pass Trail not too far from the park’s visitors center. It’s a moderate 3.5-mile incline through aspen and evergreen trees to the top of the pass. Although pretty, the top of Mosca Pass doesn’t afford wide-open views of the valley or dunes below.

Pass the time

Three classic Colorado activities you can experience in the preserve.

Fly-fishing: Bring your rod and fishing license; both Upper and Lower Sand Creek lakes fish well.

Peakbagging: July to September is the best time to climb Mt. Herard, the summit of which affords great views of the Crestone and Blanca mountain groups.

Backpacking: You can pitch a tent anywhere in the preserve so long as you leave no trace and set up your site 100 feet from water, trails, and roads.

Out of Bounds

The national park may be the main attraction, but the San Luis Valley has a few things to offer beyond the dunes.

The Attraction: Zapata Falls

The draw: A 0.5-mile walk delivers hikers to a rocky crevasse where a 30-foot-tall waterfall creates a misty refuge during hot summer days.

The drawback: Those with poor balance or an aversion to wet feet might not dig the fact that you’ll be fording the creek multiple times.

The details: From the park, drive south about nine miles on CO 150 and turn left at the sign for Zapata Falls Recreation Area. The road is an unpaved, 3.5-mile-long path that ends at a parking lot and campground. The short trail to the falls leaves from the parking lot.

The Attraction: Crestone

The draw: If you’re into religion or spirituality of any variety, this 137-person town located north of the national park might be your thing. Although Crestone’s town center offers little more than a gas station and a restaurant or two, the enclave hosts a Hindu temple, several Buddhist centers, a Zen center, a Carmelite monastery, and a Shumei retreat—plus a few New Age festivals each year.

The drawback: On a normal day, there’s not much happening in Crestone. Skip it unless you’re there for a retreat or there’s a special event, like the Fourth of July parade, the Crestone Music Festival (first weekend in August), or the Crestone Energy Fair (Labor Day weekend).

The details: From the park, take CO 150 south; go west on U.S. 160; go north on CO 17; and then take a right on Russell Street, which will take you into Crestone.

The Attraction: UFO Watchtower

The draw: The San Luis Valley has long been known as a magnet for paranormal activity, especially of the Close Encounters of the Third Kind variety. As such, rancher turned believer Judy Messoline built a 10-foot platform where groups of up to 60 can crane their necks to see…well…whatever it is people think they’re seeing here.

The drawback: This place isn’t exactly a university-level observatory. And if you’re not into ET or overlapping energy vortices, the I-was-abducted-by-aliens crowd might wear on your nerves.

The details: In the summer, the watchtower is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. You must request nighttime access. Admission is $2 per person or $5 per car. ufowatchtower.com

The Attraction: Alamosa

The draw: This 9,500-person town, located about 35 minutes from the park, has a charming Main Street and a fishable section of the Rio Grande running through town. Alamosa is also an embarkation point for the Rio Grande Scenic Railroad’s excursion trains.

The drawback: With the national park nearby, you’d think there’d be a handful of cute lodges or bed-and-breakfasts in Alamosa…but there aren’t. Instead, you’ll find the typical chains.

The details: From the park, take CO 150 south; go west on U.S. 160; and then go south on CO 17, which becomes Broadway Ave-nue and will take you into town.

Enter Sandman

Finding a place to sleep near the dunes is challenging. These options—ranging from primitive to posh—are your best bets.

On the Ground

If you’re not rolling out your sleeping bag on the dunes or in the preserve, the Piñon Flats Campground inside the park is a close-to-the-sand alternative. Be aware that in May and June the campground is often booked by late morning. Open April through October, the campground has three loops: 44 first-come, first-served sites sit in Loop 1 ($20 per night); Loop 2 ($20 per night) has 44 sites that are reservable at least four days in advance from May 4 to September 18 at recreation.gov; and the last loop, Loop 3, has three tents-only reservable group sites ($65 to $80 per night). The sites accommodate three tents and two vehicles. There are no hookups, but some sites can fit RVs up to 35 feet long. Capacity is eight people per site. There is a fire grate and a picnic table at each site, and each loop has restrooms with sinks and flush toilets. Next-Best Options: Mosca Campground (51 sites) at San Luis State Park is located 15 minutes from Great Sand Dunes, or try 23-site Zapata Falls Campground 12.5 miles from the national park. cpw.state.co.us; fs.usda.gov

Four Walls but Nothing Else

The Great Sand Dunes Lodge, which sounds like it should be located inside the park, is actually an independently owned motel-style accommodation nestled into the base of the Sangre de Cristos just minutes from the park’s entrance. It’s nothing fancy, but it’s clean, well-priced ($100 to $170 per night during high season), and conveniently located next to a diner and a general store with fuel pumps. gsdlodge.com Next-Best Options: The Oasis Duplex Motel ($99 to $159 per night), which is near the park entrance but only has two units, and the Oasis Camping Cabins ($55 per night)—rustic, primitive cabins with no linens or running water (shower facilities are nearby)—are located in front of the Great Sand Dunes Lodge. greatdunes.com

Gourmet Breakfast Included

Owned by the Nature Conservancy, a conservation organization that protects ecologically important lands and waters around the world, Zapata Ranch is a 103,000-acre bison and guest ranch that borders the park. This working livestock operation offers what it calls ranch vacations, during which guests can monitor herd health, mend fences, and irrigate farmland during the day and sink into glasses of wine, a hot tub, and fine linens at night. A highlight of staying at Zapata Ranch is the opportunity to take guided horseback rides into the national park. Stays at the ranch are all-inclusive (starting at $1,380 per person) and require a three-night minimum. zranch.org Next-Best Option: An hour from the park, Joyful Journey Hot Springs Spa offers 12 rooms (starting at $116) that come with admission to the hot springs and breakfast. joyfuljourneyhotsprings.com

Trip Tip: Your Sand Dunes Packing List

- sunscreen

- wide-brimmed hat

- sunglasses

- hiking shoes/boots

- knee-high socks (hot sand can burn your ankles!)

- water shoes (for the hike to Zapata Falls)

- cool clothes for daytime

- warm clothes for nighttime

- soap

- shampoo

- towel (there are no showers in the park, but you can buy access to the showers at Great Sand Dunes Oasis for $6)

- water bottles or hydration pack (refill them at the park’s water stations)

- tent

- sleeping bag

- flashlight or headlamp

- portable air compressor for vehicle tires (if you plan to drive up Medano Pass Primitive Road)

- leash and booties for your pet’s feet

- sand toys and pool floats

- bathing suit

- camera

- food (there aren’t many restaurants or big-name grocers nearby; bring what you’ll need with you)

- steel-frame backpack (if you plan to do any backcountry camping)

- small telescope or binoculars for stargazing

Anatomy Of A Dune Field

These structures are much more complex than the sandcastles you built as a kid.

They might look peculiar, but terrestrial dunes aren’t as uncommon as you might think. Within the National Park Service alone, there are multiple other examples of inland dune fields: You’ll find them in California’s Death Valley National Park and Mojave National Preserve, Alaska’s Kobuk Valley National Park, and New Mexico’s White Sands National Monument. These sandscapes might look the same to the untrained eye, but they are created by different forces and are composed of different structures. At Great Sand Dunes, there are six varieties of dunes, but the most commonly occurring formation is the reversing dune with its signature Chinese wall cornice. One reason Great Sand Dunes hosts the tallest dunes in North America is because of these reversing dunes, which, due to opposing wind patterns, grow atop themselves. What other sand structures will you find at Great Sand Dunes? See below for a quick primer.

Star Dunes: These multi-armed sand dunes only form at the intersections of reversing dunes and in locales with complicated wind models. At Great Sand Dunes National Park, you’ll find a large star dune complex on the northeast corner of the dune field.

Parabolic Dunes: Common in the sand sheet southwest of the dune field, these dunes are created when winds erode sections of vegetated sand. Vegetation holds the arms of the dune in place while the central part of the leeward side of the dune moves forward.

Barchan Dunes: Found near the main dunes parking area, these dunes are one of the most common dune shapes in the world. The crescent-shaped structures are produced by wind emanating from one direction. If conditions are right, they inch forward.

Transverse Dunes: When multiple barchan dunes become aligned perpendicular to the breeze, experts call the long, forward-creeping ridges transverse dunes. A series of transverse dunes are fed by Medano Creek along the southern edge of the dune field.

Nebka Dunes: These are simple sand hills that form around vegetation. At Great Sand Dunes, these dunes are visible on the sand sheet, along creeks, and near parking lots where shrubs and grasses accumulate mounds of windblown sand around them.

Starving For Restaurants

In Colorado’s largest mountain valley, we found only a handful of eateries worth the (not insignificant) drive times.

Alamosa (34 miles from the park)

San Luis Valley Brewing Company

631 Main St.; slvbrewco.com

Eat This: A Gosar sausage plate or the Blanca Burger

Drink This: The crimson-colored, 5.5 percent ABV Alamosa Amber

Calvillo’s Mexican Restaurant

400 Main St.; 719-587-5500

Eat This: The veggie fajitas

Drink This: House margarita

Del Norte (50 miles from the park)

The Dining Room (at the Windsor Hotel)

605 Grand Ave.; windsorhoteldelnorte.com

Eat This: Bone-in local lamb with celery root purée, caramelized Brussels sprouts, and wild blueberry bordelaise

Drink This: Barman Kevin Haas pours a variety of locally distilled spirits; ask him to surprise you

Three Barrel Brewing Company

475 Grand Ave.; threebarrelbrew.com

Eat This: A wood-fired calzone

Drink This: The Bad Phil, a 6.6 percent ABV pale ale with a dry finish

Trip Tip: All the Necessary Details

Operating Hours: Great Sand Dunes is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Entrance Fees: Noncommercial vehicle andoccupants: $15, Motorcycle and riders: $10, Great Sand Dunes annual family pass: $30

Free Days: Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve will waive its entrance fees from August 25 to 28 for the National Park Service’s 100th birthday. The park also offers free days on September 24 (National Public Lands Day) and November 11 (Veterans Day).

Visitors Center: Visitors center hours vary by season but are typically 8:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. daily during peak summer visitation times. For more information, call the visitors center at 719-378-6399 or visit the park’s website (nps.gov/grsa).

Campground Reservations: There are some reservable campsites in the Piñon Flats Campground within Great Sand Dunes National Park; visit recreation.gov to reserve these sites.

Conditions: To obtain information about how Medano Creek is flowing or the conditions on Medano Pass Primitive Road, visit nps.gov/grsa and click on the Operating Hours & Seasons tab. Scroll down to find the specific information you require.

Weird Science

A by-the-numbers look at one of the world’s most bizarre—and beautiful—landscapes.

1 Mammal that lives in the dune field for its entire life: the Ord’s kangaroo rat

7 Endemic species, or species that exist only in one location or area on Earth, that are found inside Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

7 Life zones—from wetlands to dune fields to montane forests to alpine tundra—on display in the national park and preserve

11 Average inches of annual precipitation the dunes receive

30 Average feet an “escape dune”—a small dune that is retreating from the main dune field—moves in one year

34 Gradient, in degrees, at which dry sand succumbs to gravity and cascades downward

1,000 Different kinds of arthropods—insects and spiders—that are known to live in the dunes

6,084 The difference, in feet of elevation, between the lowest and highest points in Great Sand Dunes

150,000 Acres of land within Great Sand Dunes’ boundaries

6,400,000,000 Cubic meters of sand estimated to make up the main dune field