The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Sometime in the afternoon on Friday, August 18, 2006, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service special agent Preston Fant climbed into an unmarked pickup and sped into the desert east of Flagstaff, Arizona. He wore a weathered pair of boots, jeans, and a collared shirt, over which he had pulled a bulletproof vest with “Federal Agent” written across the back. A handgun was holstered against his right hip.

As he drove, the majestic San Francisco Peaks, which rise prominently just north of Flagstaff and are sacred to the Navajo Nation, faded in his rearview mirror. Through the lens of Fant’s windshield, the vast desert unfurled in front of him. Undeveloped, blanketed in burnt orange and red hues, and with a line as flat as the prairie drawn across the horizon, this landscape can have a way of disorienting a person. In this moment, though, Fant knew precisely where he was headed. The home address inscribed on the federal search warrant inside his truck corresponded to a house located in Dilkon, Arizona, 50 miles down the road across the southern border of the Navajo reservation.

A community of about 1,200 residents, Dilkon is the kind of rural town that if you didn’t know it was there, you might miss it altogether. The median family income, according to a recent American Community Survey, is $22,063; more than 50 percent of residents live below the poverty line. As one member of Osage Nation describes it, American Indian communities are not exactly healthy entities these days: “After 500 years of conquest, genocide, and destruction, every Indian reservation is a place that is haunted by the communitywide specter of post-traumatic stress disorder.”

For the previous two years, Fant had led a covert investigation of the man from Dilkon. Agents named the case Operation Silent Wilderness. Almost from the beginning, it was clear the man had broken multiple laws multiple times. To build their case, the detectives needed only to ask the right questions, then listen.

Fant arrived at the Native American man’s Dilkon home at 2:44 p.m. Two colleagues and two members of the Navajo Nation Department of Fish and Wildlife accompanied him. The agents dressed like Fant, in bulletproof vests, and each carried a gun. The Navajo officers wore police uniforms and drove patrol cars. They were also armed.

Fant parked his truck and climbed out. He approached the door, knocked, and announced that he was a Fish and Wildlife agent and had a search warrant for the residence. The Navajo man in question, a 30-year-old former construction worker named Cedric Salabye, answered the door. Salabye’s girlfriend of 11 years, whom he referred to as his wife, and three children—12, seven, and one—were also inside their home. Salabye stepped outside. He and Fant walked a few paces in the summer sun to Salabye’s truck. Fant handed him the warrant. Salabye sat on the tailgate, his legs swinging nervously as he read the document. Meanwhile, Fant’s colleagues disappeared into the house to begin their search for evidence, including the feathers.

Ten miles northeast of downtown Denver, not far from Dick’s Sporting Goods Park, the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge spreads across 15,000 acres of grassy plains and wetlands. Denverites looking for respite from the sounds and movement of the city almost always head to the mountains, overlooking this peaceful spot a short drive east of the city. Hundreds of years ago, Native Americans tracked herds of bison to this place and settled there. In the 1980s, biologists discovered bald eagles nesting in the area, which sparked government interest in managing the wildlife—amphibians, reptiles, bison, coyotes, deer, raccoons, and 280 species of birds. There are a handful of buildings on the refuge, including a series of nondescript warehouses clustered in the southwest corner. Among them sits Building 128, an L-shaped structure with a sign out front that reads: “National Eagle Repository.”

Through the building’s main entrance, past a reception desk and a set of doors on the right, there is a white hallway and a long bank of windows—the kind newly christened parents might stare through, eagerly awaiting the chance to hold their newborn. The space on the opposite side of the glass resembles a medical laboratory. There are two long metal workbenches and an industrial ventilation system affixed to a wall near the ceiling. Looming large in each far corner are tall walk-in freezers, which serve the function of preserving something that is already dead.

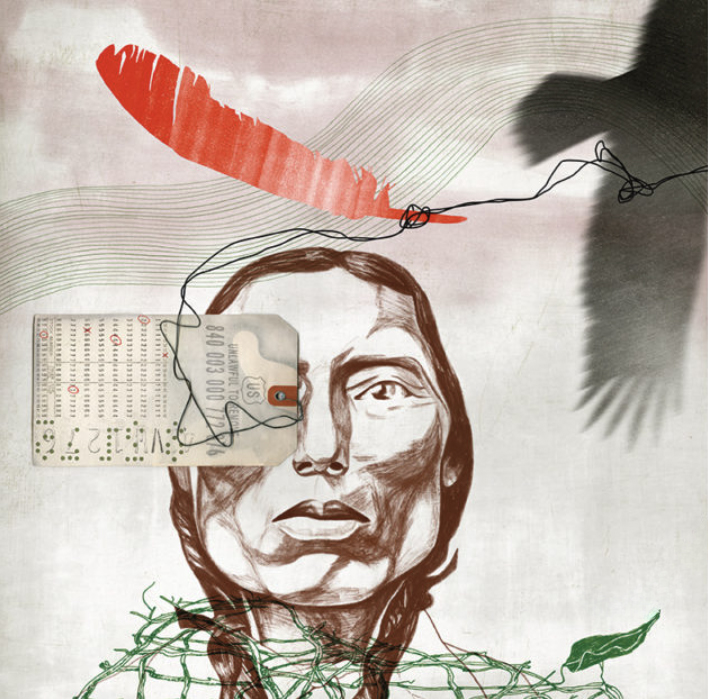

Long before the lines of the New World were drawn, the indigenous people had their own ways of doing things. There are tales of tribal men looking up beyond the clouds and, when the positions of the stars and the movements of the planets indicated the time was right, walking into the wilderness in search of one sacred item. Often carrying little more than the carcass of a rabbit for bait, the chosen few would trek until they were shrouded by silence. Each would dig a ditch in the dirt just large enough to crawl into. They would camouflage the burrows with twigs and brush and place the bait on top. Then they’d wait.

If one of the men were lucky, an eagle would descend from the sky and land on the trap. In that moment, the man would reach up from beneath the ground, extend his hand toward the sky, and grasp the majestic bird’s legs. In some versions of these stories, the man would quickly and carefully pluck a feather from the eagle’s tail, one from the very middle so as not to disrupt the bird’s ability to soar high above the earth. Then the man would release his grip, and the bird would extend its wings and, with a few flaps, return to the air.

Back then, feathers belonging to an eagle still riding the currents of the skies were considered all that much more spiritually charged and, thus, more meaningful and prized. Many animals—bears, buffalo, wolves, owls—are important to Native Americans; the eagle, though, literally and symbolically soars above the others. From the beginning, the tribes understood the eagle’s ability to glide higher in the sky than any other bird as a connection to their Great Spirit, or the Creator of all living things. They view the bird as a messenger. More than just objects or symbols, the eagle and its feathers are akin to relatives. The feathers have their own energy, their own wisdom, their own gifts to bestow upon the world.

For centuries, Native Americans have passed feathers down through generations. They are used to heal the sick. They are gifted to family members at significant times in life—the birth of a new child or the coming of age of a young man. They are also used during sacred ceremonies. Feathers are not buried; they are kept alive, always part of the family. “We’ve always connected with the eagle,” says Roland McCook, a member of the Northern Ute Indian tribe in southwestern Colorado. “We have a very special feeling and special respect for the eagle. It’s not taken lightly.”

European settlers eventually appropriated this Native American symbol after arriving on the land that would become the United States. Congress officially employed the bird as an icon of the young country six years after the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Of course, the most famous representation is the presidential seal, in which the feathered creature is pictured clutching an olive branch with one talon and a satchel of arrows with the other.

After the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. government passed laws—the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald Eagle Protection Act—that barred anyone from hunting or even disturbing the birds or their nests. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act carries a misdemeanor charge; violating the Bald Eagle Protection Act is a felony that can result in up to a year in prison and a $100,000 fine. When Congress enacted the eagle act in 1940, it declared the bird a “symbolic representation of a new nation under a new government in a new world” and said the eagle is not “a mere bird of biological interest but a symbol of the American ideals of freedom.”

It wasn’t until 1962 that Congress amended the Bald Eagle Protection Act to allow Native Americans to possess eagles and eagle feathers for religious purposes. Congress also adjusted the law to include golden eagles. Several years later, the U.S. government established the National Eagle and Wildlife Property Repository. From this building, officials legally distributed the feathers of eagles and whole birds to members of federally recognized Native American tribes. (Tribes are required to apply to the government for this designation.) The repository was first located in Idaho and moved to Commerce City in 1995.

Thirteen years after Congress amended the eagle act, the secretary of the interior, a stout Republican politician by the name of Rogers C. B. Morton, felt there was enough confusion surrounding these federal laws protecting migratory birds, particularly bald and golden eagles, that he was compelled to clear things up. He drafted a memo, the purpose of which was to “ease the minds of American Indians.”

“I am aware that American Indians are presently experiencing uncertainty and confusion over the application of Federal bird protection laws to Indian cultural and religious activities. Apparently, this confusion and concern may have resulted, in part, from this Department’s enforcement activities under such laws.”

Morton assured Native Americans that his department recognized “the unique heritage of American Indian culture” and understood that “American Indians have a legitimate interest in expressing their cultural and religious way of life.” However, he said, the government still has a “responsibility to conserve wildlife resources, including federally protected birds.”

Morton reiterated that Native Americans may possess or exchange without compensation all federally protected birds. He also noted that tribal craftsmen who work with these feathers or other bird parts may be compensated for their work, as long as the items are obtained legally. Morton emphasized that the department would continue to enforce federal laws that prohibit the killing of eagles or other migratory birds and the illegal buying or selling of their feathers. Near the end of his February 1975 memo, Morton acknowledged that the eagle repository is underused and said the government was “presently developing” a better process to distribute feathers and birds legally to Native Americans.

In August 2004, special agent Fant received a call from a member of the Navajo Nation Department of Fish and Wildlife. The officer on the other end of the line had a lead on a possible case involving eagle feathers and wanted to know if the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would help investigate. Someone had purchased an eagle feather fan for $150 from a man named Cedric Salabye. Soon after, Salabye asked for the fan back. The buyer became frustrated, dialed the Navajo department, and unloaded a verbal jackpot of information. The department learned Salabye had a room in the back of his house where he kept feathers. Some of the feathers came from Washington state, where someone would shoot the birds and use a long net to retrieve the animals as they floated, lifeless, down a river.

Ever since he was a kid, Fant wanted in on this line of work. Hunting and fishing were a way of life in the rural part of Florida where he grew up; he even wrote a paper in middle school about a game warden. By the time he was in his 20s, he was working as a wildlife officer for the Florida Game and Freshwater Fish Commission. In 2001, he took a job with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service stationed in Littleton, Colorado. The agency trained him as an officer of the law and gave him the title of special agent. After a year in Littleton, he was transferred to Flagstaff, where he settled in and familiarized himself with the casework of the area.

After the August phone call, Fant and his team first checked with the National Eagle Repository in Commerce City to determine whether the government had shipped feathers legally to Salabye’s home. They found no record of an order, and they began to dig. Less than a year later, an undercover officer posing as an interested customer contacted Salabye for the first time in person, at Salabye’s home in Arizona. Salabye answered the door and invited the man in. The officer struck up a conversation by asking how much Salabye charged for beadwork. Then he expressed interest in buying an eagle fan.

“I’m making one right now,” Salabye said. “You don’t have any feathers of your own?”

No, the officer said, he didn’t. He would have to get some.

Salabye looked through some boxes and produced a few golden eagle feathers. The plumes, he said, are often used as “drops” to hang from the hair of dancers at powwows. They can be hard to get, he explained. Salabye sold the man four feathers for $15 each. The fifth, he said, was free. He told the undercover officer he could have the fan done the following morning.

The officer returned the next day. He noticed an eagle fan on the table and asked if he could take it. The officer then asked about a second fan and Salabye said, “Yeah. Later, in the future, I can get ahold of these for you,” he said, referring to the second fan that contained longer feathers. “Give me some time, maybe two months…because the Gathering is coming up, and I usually trade with some bros over there.”

The Gathering Salabye mentioned is the “Gathering of Nations” powwow, a large, three-day celebration of Indian culture held each year in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Salabye said everyone at the Gathering is looking for feathers. He also explained to the undercover officer that eagle feathers can be obtained for free from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service eagle repository in Commerce City, but that he doesn’t bother because the wait is so long and sometimes the feathers are damaged.

One day this past spring, Denver professor Tink Tinker received a shipment in the mail from the U. S. government. Tinker, who teaches American Indian cultures and religious traditions at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, is the son of a Protestant mother and a Native American father. A member of Osage Nation, Tinker always identified with his father’s culture. (Tinker’s great-uncle, Clarence Leonard Tinker, attained the rank of major general while serving in the U.S. Army.)

The nondescript, rectangular brown box delivered by the U.S. Postal Service resembled the type of package an Amazon shipment might arrive in. Except there were two labels affixed to it: a yellow “perishable” sticker, indicating that the contents of the package would likely spoil or decay quickly, and an address label that read, in part:

U.S. Fish and Wildlife SVC

RMA, 6550 Gateway Rd., BLDG 128

National Eagle Repository

Commerce City, CO 80022

To receive this package, Tinker had filled out a lengthy government order form labeled “Eagle Parts For Native American Religious Purposes.” The paperwork asks for standard information—name, address, date of birth, phone number. The form also requires a Social Security number. Another line prompted Tinker to write the name of his tribe and the tribe’s government enrollment number. The bottom half of the page is where Tinker could indicate his order for parts of either an immature or adult bald or golden eagle—feathers, wings, tails, claws, a head, a trunk, or a whole eagle.

A box on the form indicates the average wait time for each type of order. Miscellaneous feathers can take three to six months to ship; quality feathers can take up to a year; wings and tails can take a few years; and the wait for a whole eagle could be five years. There is an asterisk at the bottom of the box: Waiting Period is approximate and may be longer than expected for all Golden Eagle Parts due to the high demand and low supply.

When Tinker finished filling out this document—he checked the box for a whole golden eagle—he delivered it to an Osage Nation tribal office, which signed off on the paperwork and forwarded the form on to Building 128 in Commerce City. That was three years earlier. Now, here was this package in the daily mail.

“You’re free to go,” agent Fant said on that day in August as Salabye sat on the tailgate, his eyes fixated on the search warrant in his hands, “but we’re going to have some questions for you, so if you stay, it will be more helpful.” Considering the circumstances—the men dressed in bulletproof vests carrying guns—Salabye listened to the agent. Fant suggested the two men speak in Fant’s pickup truck. They climbed in, and Fant began his questioning. A few seconds later, he paused, climbed out, and turned on an audio recording device. The recording begins at 2:54 p.m., 10 minutes after the officers first arrived at the house. Fant then returned to questioning Salabye about the business of selling feathers. Salabye didn’t know his conversation with Fant was being recorded.

Fant questioned Salabye on and off in his truck for a little more than two hours. At one point, Salabye asked if he could get a drink from inside the house. Instead of having Salabye leave the truck, Fant directed Salabye’s girlfriend to grab a soda. Thirty minutes into the tape, according to a judge’s statement in a court document, Salabye appeared uncomfortable with the situation. Wanting to put Salabye at ease, Fant said, “I think you’re doing the right thing by just volunteering to stay here and just talk it over with me for a minute…we shouldn’t be here too long.”

During those two hours in the truck, Salabye confessed to unlawfully selling migratory bird feathers. The agents pulled more than a dozen names and contact information from Salabye’s and his girlfriend’s phones, which provided additional leads for Operation Silent Wilderness. The men left the house around 6 p.m. after confiscating dozens of eagle feathers, hawk feathers, an address book, a napkin with a phone number scribbled on it, and other evidence. On his way out, Fant thanked Salabye for his cooperation. Before Fant climbed into his truck and headed back toward the lights of Flagstaff, Salabye remembers the agent saying: “Did you know you didn’t have to answer any of these questions?”

In the spring of 2010, President Barack Obama visited a manufacturing facility in Iowa that produces wind turbines. From behind a podium emblazoned with the presidential seal of an eagle, the president championed the clean energy industry. Some of the turbines from this facility found their way to a 17,000-acre piece of ranchland in Converse County, Wyoming, which is located about equidistant from two of Mother Nature’s more brilliant tableaus, the distinguished Colorado Rockies to the south and the geothermally magnificent Yellowstone National Park to the west. Here, Duke Energy Renewables Inc. had erected a wind farm called Top of the World Windpower Project, where more than 100 turbines capture enough juice blowing in the wind to power 60,000 homes. What the president didn’t know that day at the manufacturing facility, but what workers at Top of the World had begun to discover a year earlier, was that the turbines were killing dozens of birds—hawks, blackbirds, larks, wrens, sparrows, and golden eagles.

All told, between 2009 and 2013, 14 golden eagles and 149 other protected birds were found dead near the Duke Energy Renewables wind farms. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service investigated the deaths, and it became clear the turbines were to blame. (The dead eagles were shipped to the eagle repository in Colorado.) The department filed criminal charges against Duke Energy Renewables for violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The company accepted a plea agreement in 2013, which marked the first time a wind energy company had been criminally convicted under the law. The agreement required Duke Energy Renewables to pay $1 million in fines, pay restitution costs, and acknowledge that it “constructed these wind projects in a manner it knew beforehand would likely result in avian deaths.”

“This is a big issue right now—whether the growth in wind development will have a negative impact on eagles,” says Brian Millsap, a biologist and the national raptor coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Some reports estimate that wind projects are responsible for as many as 500,000 avian deaths a year, though few have come up with a tally specific to eagles. Despite these numbers, bald and golden eagle populations are still considered reasonably healthy.

Forty years ago, another American industry nearly eradicated the iconic bird. In the 1970s, biologists estimated there were as few as 1,000 bald eagles circling the globe. They’d become endangered primarily because of a chemical commonly referred to as DDT. The pesticide was popular among the nation’s farmers looking for a way to kill off unwanted bugs, but the chemical also harmed the environment, infecting the food chain of birds such as the bald eagle. DDT disrupted the bird’s reproductive cycle. Eagles began laying eggs with overly thin shells that failed to hatch. The U.S. government banned the chemical in 1972. Biologists had already begun to nurse eagle populations back to healthy numbers, and in 2007 the bird was removed from the endangered species list.

Recently, Fish and Wildlife designed a new permit meant to address the modern threat energy development poses to eagles. In what eventually amounts to something of a free pass, companies eyeing construction of wind turbines could apply for a license that would legally allow them to kill a specified number of eagles without threat of criminal prosecution. To receive this permission, companies would have to meet a stringent set of requirements designed to lower the chance a wind farm would maim eagles in the first place. The agency issued the first of what it calls “programmatic eagle take permits” this summer to EDF Renewable Energy for a wind farm in central California. The five-year permit allows the project to kill five golden eagles without facing criminal prosecution.

On April 14, 2009, nearly three years after undercover agents first visited his home, Salabye took the witness stand in an Arizona courtroom. About a year earlier, police indicted Salabye for selling 11 bald eagle tail feathers and charged him with one count of violating the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. The purpose of this April hearing was to determine whether the statements Salabye made to agent Fant that August day in the desert were collected legally. Salabye’s lawyer argued that the agents gave Salabye the impression he was under arrest and thus never properly instructed him that he had the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney. Fant testified that he told Salabye multiple times he was free to leave. On the stand, Salabye told the judge, “I was certain I was being [placed] under arrest.”

Two days later, the judge ruled in favor of Salabye. The judge wrote in his decision: “A reasonable person in Defendant’s position would not have felt free to leave or terminate the questioning. Because Defendant was not given a Miranda warning, his constitutional rights were violated and his statements to Agent Fant must be suppressed.”

The defense viewed the judge’s decision as a legal victory, and the two sides cut a deal regarding Salabye selling illegal feathers. In a plea agreement, Salabye pleaded guilty to violating the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. He was sentenced to five years of probation, six months of home confinement, and 150 hours of community service—no jail time. The U.S. Department of Justice issued a press release announcing Salabye’s conviction. “The buying and selling of the feathers of bald eagles, our nation’s symbol, is illegal,” an acting assistant attorney general said in the release, “and those who choose to ignore those laws will be prosecuted.”

The information the agents retrieved from Salabye that day in August helped expand Operation Silent Wilderness into one of the largest-ever covert investigations involving the illegal trafficking of eagle feathers. After eight years, 6,670 case hours, eight arrests, and 35 prosecutions, agents began wrapping up the operation this fall. In the past decade, there have been at least two other cases similar in content and scope to Silent Wilderness—all of which are tellingly similar to a 1980s case, which was code-named Operation Eagle.

In 1980, undercover agents set up a bogus business called the Night Hawk Trading Company and paid thousands of dollars to Native Americans for protected bird feathers. After two years of conducting covert purchases on the Yankton Sioux reservation in South Dakota, according to news reports, the agency charged 40 people in eight states with illegally selling feathers and, in a few instances, whole eagles. According to the 1980 census, more than half of the families on the Yankton Sioux reservation lived below the poverty line. Most of the charges stuck, but a federal appeals court tossed out two of the cases on the grounds that the agents violated the law of entrapment. Several of the Native American men, the court determined, would never have sold the feathers if it weren’t for the presence of government agents; it’s likely they were encouraged to engage in the business for the money.

One man wrapped up in Operation Eagle, Dwight Dion Sr., argued his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Dion’s lawyer contended the charges against his client should be dropped for several reasons, one of which was that his First Amendment right to religious freedom allowed him to possess eagle feathers. Dion’s lawyer also argued that a treaty signed by the Yankton Indians and the U.S. government in 1858 granted the Yankton people exclusive rights to fish and hunt animals on their land, even eagles, for noncommercial purposes. The judge determined Dion’s First Amendment right was not applicable because he used the birds for commercial gain.

The court also ruled that when Congress passed the Bald Eagle Protection Act in 1940, it superseded the Yankton treaty—meaning the justices determined the law took priority over any agreement the government had with American Indian tribes. Dion served a year in prison, and a legal precedent unfavorable to Native Americans like Cedric Salabye and others involved in undercover stings such as Operation Silent Wilderness had been set.

A public defender who has represented Native Americans in these sting cases notes that such prosecutions aren’t cheap. It is difficult to determine the exact cost to investigate and prosecute individual cases. However, in the 2015 fiscal year, which began in October, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service allotted $66.7 million for its law enforcement division, a requested $1.9 million increase from the previous year. About nine percent of that budget, or roughly $6 million, will go toward investigations involving migratory birds. “We decide [Native Americans] are sovereign when we don’t want to deal with something,” the public defender said, “and we decide they’re not sovereign when we do.”

Around the same year Salabye took the stand in the Arizona courtroom, the phone in the Washington, D.C.–area office of the Association on American Indian Affairs began to ring with Native Americans complaining about undercover stings. “Native Americans felt there was a lot of entrapment,” says Jack Trope, executive director of the nonprofit, which advocates for protecting Native American rights. “The investigative techniques encourage behavior people might otherwise not be engaged in.”

Just as Salabye had complained of the long wait times at the repository, so too had many of the Native Americans entangled in the undercover busts. At the time, Trope and his group supported allowing tribes to run their own aviaries; they also advocated for the idea that if tribal members found dead birds on their own land, they shouldn’t be required to ship them to Commerce City. Following three years of talks, in October 2012 the Justice Department released what amounted to a reissuing of the memo Secretary Morton typed out in 1975 intending to “ease the minds of American Indians.” Outgoing Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., one of the highest-ranking members of the U.S. government, signed the memo reiterating a four-decades-old sentiment: “The Department of Justice is committed to robust enforcement of federal laws protecting birds while respecting tribal interests in the use of eagle feathers and other federally protected birds, bird feathers, and other bird parts for cultural and religious purposes.”

Fant says the laws enacted by Congress decades ago are there to protect the wildlife and that the agency seeks out the worst violators. “We have a method, a structure, a process set up to obtain these feathers legally,” Fant says. “If you want feathers now, you need to anticipate it and ask early. We need to protect the birds. The statutes are there for a reason; a number of defendants in this case showed a lot of remorse. I think a lot of it is, ‘I’m sorry I got caught; maybe I didn’t think it would ever happen to me.’ They’re believers now.”

Three years after filling out the paperwork, Tinker opened the brown box from the government. He carefully lifted a golden eagle, frozen and wrapped in a plastic bag, from a bed of dry ice. “We don’t talk about plastic; it’s such an unappealing way to talk about a relative,” Tinker says, explaining the proper ceremonial way to speak about and care for a bird. “I can’t say that I knew that eagle at all. I have only begun to build a relationship with it, but it’ll come alive again as we use those feathers.”

Stories about the repository circulate via word of mouth among tribal communities. There’s the one about a tribal elder waiting years for a package only to open the box and find a goose. There are tales of feathers being damaged to the point of being unusable. Or of packages being shipped to the nearest post office and it taking days for a Native American to collect gas money to pick up the box, only to find the bird has rotted. And the wait times balloon into lore—up to seven years, some say. “You’re taking a chance with the repository,” says Kenny Frost, a Native American consultant and a citizen of Colorado’s Southern Ute tribe. “It’s a lot of paperwork, a lot of bureaucratic white tape—almost to the point of giving the government your firstborn. And if the plumes and feathers aren’t in good shape, you’ve waited five to seven years for something you can’t use.”

Some Native Americans say that to properly perform sacred ceremonies, they must capture a bird the traditional way in the wild, just as their ancestors did. The government does have a permit allowing Native Americans to capture eagles in this manner; since 2001, there have been 23 applications, eight of which have been approved.

In 2005, a member of the Northern Arapaho tribe—who later testified that he didn’t know the capture permit existed—shot and killed an eagle on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming. The man said he planned to use the eagle in a sacred sun dance ceremony. Someone turned him in, and the government prosecuted the man for violating the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. At the trial, another member of the tribe testified, “You know, you don’t have a repository for the Bible, and our bible is from Mother Earth alone.”

A federal judge dismissed the charges against the American Indian man. The judge wrote in his decision, “It is clear to this court that the government has no intention of accommodating the religious beliefs of Native Americans except on its own terms and in its own good time.” The judge’s decision was later overturned and the man faced a year in prison. His case was eventually moved to a tribal court that sentenced him to a $2,500 fine and suspended his hunting privileges for a year.

Yet another Native American arrested in a government sting op had this to say: “No matter what tribe you come from in this country, the majority of every tribe uses these feathers in their ceremonies. And when they passed this law protecting the eagle, they forgot about the Indians. We don’t have much left as Indian people. Most of our land has gone to the government. Everything has gone to the government. The only thing we have is our culture and our identity as Indian people. And now they want to take that away from us.”

Tinker requested the golden eagle from the repository so that he could share the bird’s spiritual meaning with his tribe. Buying and selling the bird as if it is a commodity, he says, is not the answer, not the Indian way. But along with other Native Americans, Tinker is also angered by the bureaucratic obstacles the repository presents. “We’re somehow privileged by the government because we have access to eagle feathers,” Tinker says. “That abjection is confirmed by this process of having to call upon that nation that destroyed our nations to ask permission if we can have an eagle.”

The lab inside the National Eagle and Wildlife Property Repository, Building 128 in Commerce City, is most often staffed by a man named Dennis Wiist, a 19-year employee of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The agency has sent Wiist and the few others who occasionally handle the birds kept at the repository to Native American sensitivity training. Employees of the office have also traveled the country to consult with various tribes on best practices for handling the eagles. No Native Americans currently work in the building, though the office has employed tribal members in the past.

In March of this year, the agency hosted an Eagle Summit in Commerce City, a gathering of federal employees and dozens of members of Native American tribes to discuss the repository process and how to improve communication between the government and tribes. Previously, the agency hosted summits in 2010 and 2011. Native Americans have raised a variety of concerns at the meetings, including wanting more notification when agents work cases on tribal land and asking that tribes be allowed to run their own eagle repositories. The department determined no tribal repositories would be authorized by Fish and Wildlife because they “would circumvent the fair and equitable first-come, first-served process the National Eagle Repository employs.”

A few changes to the repository process aimed at decreasing wait times were agreed upon at the recent summit. Native American prison inmates are now only allowed to place a single order; the agency will update its website to include an online re-order application; and the application will be amended to indicate that Native Americans can order fewer than the maximum number of feathers. “The religious importance of eagles to many Native American tribes can’t be overemphasized,” says U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service special agent Steve Oberholtzer, who oversees the repository. “We’re honored to be able to help facilitate those religious pursuits of tribes.”

When Wiist works with the birds at the repository, he wears a white medical suit, white gloves, and a mask covering his nose and mouth. “Rarely is there an eagle that doesn’t have a feather or something left on it that we can make use of,” says Wiist, who stood in the middle of the laboratory this past summer explaining his process. “We also check the tail plume feathers. There are actually some plume feathers under the wings as well, but they’re not as large and straight as the tail plumes.”

Wiist has handled more eagles than anyone else in the country, maybe the world. He has plucked feathers for each of the roughly 42,000 orders filled at the repository since the building opened in 1995. The repository receives about 2,500 birds annually, and each year the agency ships approximately 4,000 orders for eagles and eagle feathers to Native Americans. (Approximately 1,200 of the yearly orders are for whole eagles.)

One day this summer, Wiist prepped the weekly shipment—a few dozen brown mailing boxes stacked on a wooden pallet just outside the laboratory doors. Each box was affixed with an address label and a yellow “Perishable” sticker. The demand for eagle feathers requested by Native Americans such as Tinker far outpaces the number of boxes stacked on these pallets each week. The current waiting list has roughly 7,500 names on it.

When it’s time to conduct the work of filling those orders, Wiist sometimes begins by opening one of the large freezers in the corner of the lab. He steps into the cool box and is immediately surrounded by hundreds of dead eagles. Each bird is individually encased in a plastic bag. Some dangle from metal bars like carcasses at a slaughterhouse. Others are piled on shelves or occasionally on the floor. The bags are cinched tight at the tops. To an untrained eye, it’s difficult to tell that the bird is a bird at all. The creature appears only as the color black, interrupted by splotches of white. Look more closely, and you might be able to make out a talon or a head or beak.

Wiist selects a bag and returns to his workbench. He pulls out the eagle, lays it on the metal table, and begins examining the bird for usable parts. The parts will be tagged, bagged, boxed, and then shipped to Native Americans by federal employees of the U.S. Postal Service. The boxes often travel to their final destinations in the back of a truck emblazoned with the USPS logo: a soaring eagle.