The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

We are wordsmiths. Yet tasked with putting together a cohesive description of what it means to be a Colorado woman proved exceedingly difficult. So, we finally went with a list of what we think are apt adjectives. Unlike women in other regions of the country who still cart around age-old stereotypes—Southern belles are all manners and makeup with an overwrought sense of historical significance, while women from the Northeast pair biting wit and a healthy dose of provincialism with their tailored black pants and stilettos—the 2,628,487 women who call themselves Coloradans do not fit snugly into a one-size-fits-all label.

Don’t get us wrong; those of us who choose to live in the thin air have some things in common. We believe wearing godsent, cheek-lifting yoga pants to places other than the studio—like Whole Foods, lunch dates, and occasionally the office—is perfectly acceptable so long as we do, in fact, attempt downward dog that day. Because feeling like Bambi on ice is not as cute as Disney portrayed it, we have collectively decided that Danskos and flat-heeled boots qualify as sexy. We also have an unspoken agreement that ChapStick and a swab of mascara count as “done up.” But these are just the superficial ties that bind, and we are not a particularly superficial bunch. Instead, whether we were born here or moved here, over time we assume personality traits and profound beliefs that—without oversimplifying things—seem derived from living in an immense landscape that demands resourcefulness, competency, independence, and an inextinguishable spirit.

To wit: Colorado women know no good comes from caring too much about what others think or say—or about what they do with their own lives. Colorado women understand that a long run or a bike ride is cheaper and often just as effective as therapy. They don’t need men to shovel snow or build fires or drive slick mountain roads or carry their ski gear, but they do need their partners to want to do those things anyway. Colorado women love their kids, but, by and large, they are not cooers or goochie-goochie-gooers. They want their children to be healthy (organic produce, check!), active (two-year-olds can so ride the lift), and self-reliant (you know where the fridge is, young man). Colorado women do not sit in the corner and let others (ahem…the guys) make all the decisions. They don’t want anyone, however, to mistake that fortitude for a lack of compassion, desire, or concern. Colorado women bring all of those things to the table as well. Call it self-assurance, or irrepressibility, or whatever word suits you. We just call it life in the West. This is how we live it.

Who Inspires You?

Successful people rarely get to where they are without support from someone. We asked some of Colorado’s most noteworthy women to tell us about the influential people in their lives.

Tami Door

President & CEO, Downtown Denver Partnership

“An old boss of mine, Dick Blouse, the former CEO of the Detroit Regional Chamber of Commerce, always said, ‘You can make widgets or you can make a difference—or you can do both.’ What he meant was so many people think they have to choose a specific job or role to be able to make a difference in the world, that their normal jobs don’t rise to that level. But he felt that you can do any kind of job and make a difference so long as you do your best and make a difference to those around you.”

Theresa Peña

Educational Activist

Most influential role model? “My mother, Annabelle Peña-Wickard.”

What did you learn from her? “I learned assertiveness, laughter, love, independence, confidence, and kindness. Her mother was a food-service worker; her father was a mine worker and then a barber. All of their kids graduated from college. My mother was one of the first generation of minority women who had the opportunity to attend college, so it was important to her that my brother and I achieved not only their levels of opportunity and ambition but also exceeded them. My mom was also the only girl in her family, so she was very assertive. She set ambitious goals and would reach them. She instilled that principle of dreaming big and going after big goals in me, but she also taught me to use those gifts to give back to the community.”

Joan Slaughter

Executive Director, Morgan Adams Foundation

“I love Rosie the Riveter. She stands for all women who aren’t afraid to step into roles they didn’t have before, take charge, be bossy when they need to be, learn new skills in order to kick some butt in whatever setting they’re in, and create something powerful in the process.”

Karen Sugar

Founder & Director, Women’s Global Empowerment Fund

“There is a group of women in northern Uganda, who were my first clients, who have been influential in my life. These are women who, when I first met them, were fresh from conflict, violence, and poverty. They taught me grace, courage, sisterhood, how to care for one another as part of a community, and the resilience of the human spirit.”

Cary Kennedy

Chief Financial Officer & Deputy Mayor, City of Denvery

“Gail Schoettler, the former lieutenant governor and state treasurer, has been an adviser to me on public finance and leadership throughout my career. She’s a great leader and always pushed me forward. She taught me to appreciate the importance of serving in a leadership position.”

Maria Belew Wheatley

Former Executive Director, Colorado Ballet

“My high school homeroom teacher encouraged me to go to college. I grew up in a poor farm family, so none of my siblings had gone to college. It wasn’t in my family’s expectations. She is the reason I realized that I could.”

Frances Koncilja

President & Shareholder, Koncilja and Associates

“The one person who continues to be a great inspiration to me is my grandmother, Lucia DiTella. She came to this country when she was 14 years old to an arranged marriage. She came from Italy and didn’t speak English. She was incredibly smart, and although she had limited opportunities, it never made her bitter. She had a great zest for life.”

Happy Haynes

Vice President, Denver Board of Education; Director of Civic and Community Engagement, CRL Associates

“Rachel Noel, a former board of education member and CU Regent—the first African-American woman elected to both of those positions—embodied two values: using education to reach high for your goals and a commitment to giving back to the community. Those two values, which she taught me, are the reasons I am where I am, and they continue to drive me.”

Jennifer Jasinski

Chef-Owner, Rioja; Owner, Euclid Hall, and Bistro Vendôme

“I have two distinct role models. In my personal life, my mom. My mom is a brilliant businesswoman, and she taught me how, in the restaurant industry, one must look at the guest perspective first. Professionally, Wolfgang Puck. Wolfgang taught me to be detail-oriented and to be the best at whatever it is that you happen to be doing, no matter how menial the task may be.”

Jeanne Robb

City Council Representative, District 10

“Federico Peña inspired me. He was mayor of Denver shortly after I moved to the city. I felt he was very good about representing all the people of the city. He had a great model of inclusivity, and he really appreciated all of Denver’s neighborhoods. He started a kind of renaissance in Denver of urban development.”

Diana DeGette

U.S. Congresswoman, Colorado’s First District

“I have had three major inspirations in my life: my grandfather, Alex Rose, who had an eighth-grade education but urged me to follow my dream of going to law school. The second is Pat Schroeder, who taught me to stand up strongly for what I believe in and be a leader on those issues. The third is John Dingell, the senior member of the U.S. House of Representatives, who took me under his wing when I came to Congress and really taught me to be a legislator.”

Kelly Brough

President & CEO, Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce

“I believe everybody has strengths and that we can learn from those strengths. Often we think role models are going to be at a high level or in a leadership role, but for me some of the most powerful lessons have come from people who don’t have positional power but have used their strengths to accomplish something great.”

Alison E. Zinn

Senior Associate Attorney, Wade Ash; President-Elect, Colorado Women’s Bar Association

Who has been your most influential role model? “My high school English teacher, Michael Mariani.”

What did you learn from him? “When I was in ninth grade, Mr. Mariani pulled me aside and told me that I had exceptional leadership skills and that he wanted me to make the most of those skills. This was something that had never occurred to me. He followed this compliment with advice as to what I should do with these skills in terms of leadership opportunities for students, but he also offered valuable advice about life that has stayed with me for 20 years. Mr. Mariani taught me never to ask why, but instead, why not? Also, he taught me that a person’s only limitations are the ones she places upon herself.”

Valencia Faye Tate

Director for Global Diversity, Equality and Inclusion, CH2M Hill

Who has been your most influential role model? “My parents, Irene and Henry Wilson.”

What did you learn from them? “They were both amazing people; not college-educated, but they had incredible wisdom. From my father, I learned the importance of an education and giving back to others. He also taught me tremendous love of family. From my wonderful mother, I learned patience, kindness, style, and grace.”

Historically Significant

Colorado women have long been a force to reckon with.

1859

Freed from slavery, Clara Brown makes her way to Denver, reportedly the first black woman to do so during the Gold Rush, and opens a laundry in Central City.

1859

Chipeta marries Ute Chief Ouray and begins improving relations between their tribe and white settlers. She travels to Washington, D.C., to negotiate a treaty and, following her husband’s death, continues advocating for peace.

1887

Frances Wisebart Jacobs, Denver’s “Mother of Charities,” establishes what is now the United Way. (In 1892, she also creates what is today called National Jewish Hospital.) She is the only woman with a stained glass window in the state Capitol’s dome.

1890

Mary Elitch Long opens Elitch’s Zoological Gardens with her husband; after he dies a year later, she continues running Elitch’s for the next 26 years, becoming the first woman to own and manage a zoo in the United States.

1893

Eliza Routt, wife of Colorado’s first state governor John Routt, becomes the first woman registered to vote in Colorado—the first state to adopt women’s suffrage by popular vote.

Katharine Lee Bates pens the lyrics to “America the Beautiful,” jotting them down as she admires the view from Pikes Peak.

1895

Clara Cressingham, Carrie Clyde Holly, and Frances Klock are elected to the Colorado House of Representatives, becoming the first three women elected to a state Legislature anywhere in the country.

1896

Mary Lathrop passes the bar and becomes the first female member of the Colorado Bar Association and the first woman to practice law in Denver. Lathrop later becomes the first woman to argue before the Colorado Supreme Court.

1897

Dr. Susan Anderson, fondly known as “Doc Susie,” moves back to Colorado after graduating from medical school and is the only female doctor in Fraser for 49 years. Lacking the means to buy a horse or a car, Anderson treks to patients’ homes on her Norwegian snowshoes.

1912

Margaret “Molly” Brown, who lived in Leadville and Denver as a young woman, gains attention for her heroism during the sinking of the Titanic, which she survives.

Josephine Roche becomes Colorado’s first policewoman. Years later, she becomes the first woman to run a major coal company. After running for governor in 1934, Roche is named Franklin Roosevelt’s assistant secretary of the treasury and finds herself the second woman to sit in a presidential Cabinet.

1917

Florence Sabin of Central City becomes the first female professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. After “retiring” in Colorado, she works in public health, helping cut Denver’s tuberculosis rate in half. She is one of two Coloradans featured in the statuary hall of the U.S. Capitol.

1925

After graduating high school at 15, college at 17, and working her way through medical school, Dr. Frances McConnell-Mills becomes Denver’s first city toxicologist..

1932

Helen Marie Black helps found the Denver Symphony Orchestra and subsequently acts as its business manager for more than 30 years.

1935

Jane Ries opens her own firm to become the first female landscape architect in Denver and the third person ever to obtain a landscape architecture certificate in Colorado.

1939

Longtime Denver resident Hattie McDaniel becomes the first African-American to win an Academy Award when she earns an Oscar for her supporting role as Mammy in Gone with the Wind.

1952

Margaret Curry becomes the first female parole officer in the state. The native Coloradan uses her position to fight for equal rights and rehabilitation and education programs for

women prisoners.

1962

At 14, Carlotta Walls LaNier was the youngest member of the Little Rock Nine, the group that integrated Little Rock Central High School. For safety reasons, LaNier’s family moves to Denver after she graduates. LaNier later receives her degree from Colorado State College.

1965

Rachel Noel, the first African-American to serve on the Denver Public School board, introduces the “Noel Resolution,” which ultimately leads to the integration of the city’s public schools.

1968

Reynelda Muse becomes not only the first female, but also the first African-American, news anchor in Colorado when she starts at KOA-TV. Twelve years later, she is one of the founding anchors at CNN.

1972

Arie Taylor becomes the first African-American woman to serve in the Colorado Legislature. During her six terms in the House, she is known as an ally for women and the poor.

1973

Denver native Emily Howell Warner is hired by Frontier Airlines, becoming the first woman pilot for a major U.S. airline. Three years later, she becomes the first woman to earn her captain’s wings.

1977

Selected as the first woman president of the Colorado Mountain Club, Gudrun Gaskill works tirelessly for the next 11 years to complete the Colorado Trail, which stretches from Denver to Durango.

1996

Lieutenant General Carol Mutter, born in Greeley and a graduate of the University of Northern Colorado, is the first woman promoted to Lieutenant General in the U.S. Marine Corps.

1997

Madeleine Albright is named the first female secretary of state under President Bill Clinton. Born in Prague, Albright moved to Denver in 1948 when her father accepted a teaching spot at the University of Denver.

1999

While working for Boulder’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Susan Solomon receives the National Medal of Science for her work explaining the Antarctic ozone hole and advancing understanding of the global ozone layer.

2005

Condoleezza Rice, who received her bachelor’s degree and Ph.D. from the University of Denver, becomes the first black female U.S. secretary of state, serving under President George W. Bush.

2008

As the president and chair of the board for the Denver 2008 Host Committee, Elbra Wedgeworth, the first black woman to hold the position, is chiefly responsible for bringing the 2008 Democratic National Convention to Denver.

2010

Time includes Temple Grandin, a CSU professor, in its list of the “100 Most Influential People in the World.” One of the country’s best-known autistic adults, Grandin publishes insights into animal behavior and lectures on autism and livestock handling.

2012

Coloradan Katherine Archuleta becomes the first Latina to lead a presidential campaign as national political director. In 2013, President Barack Obama nominates Archuleta as director of the Office of Personnel Management.

Eighteen-year-old swimmer Missy Franklin, who grew up in Centennial and attended Regis Jesuit High School, takes home four gold medals and one bronze medal and sets two world records at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.

Her Honor: Two Colorado Supreme Court Justices Speak on Women’s Issues

We ask Colorado’s only two female Supreme Court chief justices to reflect on issues facing women today, historic changes to the law, and where we might be headed next.

What are some legal issues Colorado women face or faced during your time on the court?

Nancy Rice: Incoming chief justice in 2014: Family issues, which aren’t necessarily women’s issues, but sometimes tend to have a bigger impact on women. And those family issues tend to be domestic violence, partner violence, spousal violence, division of parenting time, child support, and raising children.

Mary Mullarkey, 1998 to 2010: The biggest issues had to do with dissolution of marriage, particularly the division of property and allocation of parental rights. Improving the way divorces, which had started to explode, are handled was a big effort then.

How have the courts tried to address some of those issues?

NR: Colorado has set up in our courts ways for anyone—not just women—to get help, irrespective of whether they have a lawyer or not. We have self-represented litigant coordinators. So if you’re representing yourself, you can come in and get some help.

MM: We created a position called case managers, who are lawyers who work for the courts. They meet with the parties and resolve whatever issues can be resolved, so by the time the case goes to a judge, it’s limited to issues that really can’t be agreed upon by the parties.

What other changes have you seen?

NR: I graduated from law school in 1975, and at that time, there were not that many female lawyers. Out of a class of about 120, there were only 15 of us. Now I teach at the University of Colorado and the University of Denver law schools, and I can tell you it’s at least 50 percent female. That’s the most visible difference. In today’s Colorado Supreme Court, there are three women on the court out of the seven. And while it’s still a very big deal to be a chief justice or a justice, I don’t think it’s such a big deal to be a woman justice or a woman chief justice, and, frankly, that feels great to me. I don’t talk or think about it much. It doesn’t come up, and that’s the way it ought to be.

MM: If you look at the courts and where we are and where we should be, there are still not enough women judges. The Colorado Supreme Court looks pretty good, but there are not that many on the Court of Appeals, and there’s not a proportionate number on the district courts, either. Also the percentage of women as partners in law firms is not anywhere near where it ought to be. I think women have to keep pushing on those issues. If they want change, they’re going to have to make that happen…. In the future, I think there are going to be legal changes having to do with pay equity issues. The situation for women really hasn’t gotten a lot better in the past 20 years. The pay gap is still there.

Marsh v. University of Denver

Wage disparity may land a local law school in court.

June marked the 50th anniversary of the Equal Pay Act, which aimed to eliminate wage disparity based on sex. One month later, on July 9, 2013, longtime University of Denver law professor Lucy Marsh, 72, initiated a charge of discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), asserting the Sturm College of Law breached the terms of the Equal Pay Act by compensating her less than a man in a similar job. According to the filing, Marsh earns $109,000 and is the lowest-paid professor at Sturm, even though she has been a full-time professor there since ’82. (The median full-professor salary at the school is $149,000.) Documentation included in the filing also shows the median salary for female full-time professors at the college is $11,282 less than that of their male counterparts. At press time, the EEOC was waiting for salary information, potentially covering the past 30 years, from DU. “The EEOC said they are particularly interested in this case,” says Jonathan Boonin of Hutchinson Black and Cook, the firm representing Marsh, “because it combines two of President Obama’s priority issues: enforcing equal pay and investigating systemic violations.”

An Open Letter to the Women of Colorado

When Patricia Schroeder was elected in 1972, she became the first woman to represent Colorado in the U.S. Congress. Over her 24-year congressional career, Schroeder had a major impact on women’s rights and family issues and gained a reputation for biting quips. She retired in 1997 and now resides in Florida, but the beach hasn’t dulled her wit, as evidenced in this note to today’s generation of women.

Dear Next Generation,

When I became co-chair of the Congressional Women’s Caucus with Congresswoman Olympia Snowe (R-Maine) in 1983, we had a goal. We wanted to have as much done with regard to women’s equality by the 21st century as possible. Sadly, despite more than two decades of work, we didn’t get many of the things passed we had hoped for: equal pay enforcement, adding the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, legislation giving women control over their reproductive health, and a family leave act to be proud of.

It took nine years—and a serious watering down—to pass America’s Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), which I authored, in 1993. At the time, pediatricians said four months was the absolute minimum we should give women and men to bond with their children.

We got 12 weeks.

This year is the Family and Medical Leave Act’s 20th anniversary. I was invited to Washington to celebrate its passage, but I refused to go. I am embarrassed this country only gives 12 unpaid weeks to women who work in companies that employ more than 50 employees. It’s pathetic.

The Family and Medical Leave Act’s passage did not stop American industry, as was predicted, and yet Congress still has not moved to increase the number of companies covered or increased the benefits. Work and family issues remain mainly “women’s issues” in our country. Not so in others, where children are seen as the future, and people believe it’s essential to invest in them with great family leave policies, childcare, college education, and medical care. In the United Kingdom, for example, every woman is guaranteed 52 weeks of family leave upon the birth of a baby, and, in many cases, 39 weeks are paid.

In America, we see your children as your problem. There have been many articles lately talking about couples deciding not to have children because of the financial stress it imposes. How is that good for America’s future?

In 2020, we will celebrate women having had the right to vote for 100 years. But there is still much work to do. I collected some headlines from stories last year and changed the word “women” to “men.” Take a look and tell me we women don’t have any more work to do. I dare you.

Are Men Fit to Lead?…Kids Getting Fat Because Fathers Not Cooking Meals…Do Men Have Too Many Choices?…Kids and Career—Can Men Really Have it All?…Makeup Tips for Men Who Look Tired At The End of the Day…Single Men: They’re Buying Homes and Working at Jobs But Are They Happy?…How Men’s Liberation is Making Men Unhappy.

To the 20-, 30-, and 40-year-old women of today, it’s time to hand you the torch. But are you ready to take it? Many of the young women I meet today remind me of women I met in Iran during a congressional visit in 1974. I asked these Iranians if they were worried about all the “noise” in the political arena about getting women back under control. They said the shah would never let that happen. He had Westernized the country, and they bragged they had better daycare and work family benefits. Well, their complacency blew up in their faces. Within years, they were being arrested if they were not fully covered outside of their homes.

Women’s rights in America made terrific advances in the 1920s only to be derailed by the Depression. Then World War II brought all sorts of advances for women, only to be derailed by the 1950s. Just last year, many states undercut rights women had won, and Congress nearly killed the Violence Against Women Act. So, ladies, complacency is not a solution. Women must do what we did decades ago: Get into the debate, vote, and make your voices heard.

My generation did a lot of grading of the road to create equality for women. Now you need to pave it.

My Best,

Pat Schroeder

How To Kick Ass In A Man’s World

Desi McAdam knows well what it’s like to work in a male-dominated business. For the past decade, she has braved the testosterone-rich tech industry—a sector that’s only about 25 percent female—and learned to navigate the sometimes geek-forward misogyny for which it’s known. As a developer and managing director for Thoughtbot, a software development company, McAdam, 37, says her community can be a great place for women—if they’re willing to adapt. McAdam offers advice for women who know they can do anything the guys can do (only better).

Read up on the imposter syndrome—that phenomenon where despite evidence of your competence, you are convinced you are a fraud and do not deserve the success you’ve achieved—because it’s real and I think pretty common among women. Knowing it’s real helps me stop that thought process.

Don’t send cues that make you easily discountable. Do not apologize all the damn time. Do not say, “I may be wrong about this, but….” Do not giggle. Do not let on that you’re nervous. Do not say, “I’m not good at this stuff so….”

Tell the men you work with to knock it off with the sexist jokes. I’m not a fan of going the HR route unless something is really egregious. Instead, I think you should just say you’ve had it with the “That’s what she said” jokes. Being direct works with men. Try it sometime.

Find some like-minded women who are at a similar level professionally as you are and talk to them. Vent. Laugh. Ask for advice. You need some female allies when you work with dozens and dozens of men.

One way to kick ass in a man’s industry is to try to make it more of a woman’s industry—encourage other women to get into the business through mentoring and helping them to be successful in the interviewing process as well as in the work environment.

Don’t be afraid of criticism. In my industry, there’s a lot of public critiquing, and it seems like women often avoid it—they avoid it so much so that it can be difficult to hire them because none of their work is available to review online. I know to ask to see it, but big companies aren’t going to take that extra time.

Understand that men and women think differently. They give and receive feedback differently. It doesn’t mean a man is being cruel when he says, “I wouldn’t have done it that way.” It just means that’s not how you would have said it.

Recognize that you have unconscious biases, too. I do my best to encourage qualified women to interview with my company and with others, but I have, at times, found myself leaning toward hiring a man simply because he is the prototypical developer and is there in front of me interviewing.

Negotiate. It’s thought that negotiating alone could account for much of the income disparity between men and women. Aside from salary, we also must learn to negotiate with clients and co-workers every day. If you don’t stand up for yourself and your needs, who will?

Sugar & Spice

Why I don’t just want to raise a daughter to be everything nice. By Hilary Masell Oswald

I’m waiting for the guy at the Whole Foods fish counter to finish scooping up shrimp for a woman with twin girls who look to be about eight years old. I’m daydreaming, absently watching her kids play in the simple ways children have of entertaining themselves in otherwise boring situations, when she catches my eye and smiles. I smile back.

Nodding at my protruding belly, she asks, “When are you due?”

“May.”

“Is this your first?”

“Yup.”

“Do you know what you’re having?”

“A girl.”

It begins. Again. I brace myself.

“Girls are tough,” she whispers loudly and raises an eyebrow, like she’s letting me in on a real conspiracy, ushering me into a club of condemned parents. “They’re just so much more complicated than boys.”

I shrug and hear myself fake a chuckle. “Well, we can’t return her now.” That’s awful. I cringe and try again, “We’re just hoping for a healthy baby?” I wonder why that sounds like a question. The woman nods as if she knew I would say that. She saunters by me and pats my back. “Good luck!”

I could ignore her, except she’s not the first to offer her perspective on daughter rearing. Over the past four months, no fewer than a dozen people—men and women—have said things that make me feel like I have won the baby-growing consolation prize:

“Well, just remember: She’ll hate you from the time she’s 13 until she’s 21.” (Great. Something else to worry about when I’m wide-awake at 3 a.m.)

“Oh, good! Girls have the cutest clothes.” (I suggested we just get a doll, but my husband wanted a real human being.)

“What does your husband say?” (About what?)

They tell me that girls are emotionally wild and exhausting, too needy or too aloof. They assume my husband would like a boy someday and suggest we could try again, as if we had failed to get it right the first time. In every single instance, I reply politely. I smile and nod, shrug and grin. I’m a first-time mom. What do I know? Maybe I am gestating the next Lindsay Lohan.

Later, as I lie on the couch trying to decide if my ankles are swollen or just, you know, muscular, I think about these conversations. Denver’s typically easygoing personality, its live-and-let-live mentality, makes these conversations especially puzzling. We live in a land where pot is legal and where the guy in charge is a geologist turned brewpub owner turned politician. Within the first few weeks I lived here, I witnessed an especially prickly political conversation that ended when one guy simply said to the other, “Want to go for a bike ride?”

So in this place where people impugn almost nothing—except a full-price lift ticket—why do some of us feel so comfortable making rash indictments of women? I lug this question with me for weeks, foisting it on whoever will listen. I’m obsessed. My husband hugs me, assures me he is thrilled with a daughter. My mom-friends wave their hands in dismissal, pointing out that people say crazy things to pregnant women. (True.) Everyone tells me when the baby is born, I’ll forget all about it. But here’s the thing: I don’t want to forget. These conversations have awakened something inside me that is both disorienting and powerful, even if I can’t articulate what it is.

One night weeks later, as I’m watching my husband assemble the crib, I dredge up the topic again: “What is it about girls that makes people say such things? And without a hint of hesitation?” I ask. My husband is quiet for a minute. “I don’t know,” he says gently. “But the biggest mystery for me is why you let them get away with it. You’re not exactly shy.” He is a master of euphemism.

His words are a swift kick to my psyche. He’s right: I’m a journalist. I talk to people for a living. I ask them questions their own mothers wouldn’t ask. I think back to grad school in Chicago, where I wrote about the federal court for a news service. Many days I ran through the courthouse, chasing down defense attorneys representing city officials who had been accused of fraud and racketeering. Once I even followed a lawyer into a cab, desperate for a quote. (I got it.) So he’s right: I’m not timid, and more to the point, I think of myself as confident, with enough chutzpah to speak up in the face of injustice or just plain ridiculousness.

It’s only then I realize the question I should have been asking is much more personal: Why didn’t I stand up for my daughter? For myself? For the women I know and love? I wonder what kept me from rolling my eyes, sighing loudly, and saying, “You’ve clearly been watching too much Mad Men.”

The truth is, I didn’t want to be rude. By being polite and demure, I was saying, “No, look! You’re wrong! We’re lovely, we girls.” Somewhere in my definition of womanhood is a code of manners and a desire for approval, a wish never to be out of bounds. Internally, I want to indict these people as small-minded bigots, and yet I’m clearly guilty of the same thoughts: Girls should be pleasant. Girls should be polite. Girls should be sweet. And above all else, girls ought to be nice, right?

The problem is our collective definition of nice: When it comes to girls and women, nice too often means timid, soft-spoken, discreet, overly courteous, reticent, and pleasing. We expect—and teach—our mothers, sisters, and daughters to be completely unobjectionable to others, so we grow up believing that being liked is the ultimate triumph. In short, being nice has long meant being a doormat.

My thoughts shift. I begin to worry less about stretch marks and whether or not I should’ve registered for a wipe warmer. Instead, I start imagining my daughter not as a baby, but as a girl who will grow into a woman. And I begin to think about what I want her to know about being a part of the “nicer” sex—namely, that she does not have to be so darn nice.

I do not pretend to know exactly how I will teach my daughter all I believe she needs to know to be a woman who is both bold and tender, fierce and gentle. But I think it begins with me remembering that I will be the first woman she knows and the most important teacher she’ll have. What do I wish for her to learn from me?

My hopes come pouring out.

I want her to be unflinchingly compassionate, even if that means she must endure the sting of being disliked. As a child, I want her to insist on fairness on the playground and tenderness for the awkward kid in fourth grade who smells a little like kitty litter. Do you remember him? I do, and to this day I wish I had shared my lunch with him or invited him to my birthday party. By the time she’s an adult, I want her to have learned that sometimes sacrificing social standing or turning down a promotion or taking an unpopular stance is worth it for the earnest pursuit of maintaining one’s integrity.

I want her to take risks, some of which may require a level of audacity that will not fit into anyone’s definition of genteel. For a lot of my life, I’ve been too enchanted by the warm-fuzzy of an accolade—and so I’ve stuck to the things I know I do well. But many of my life’s greatest joys have come from my boldest decisions, from the times I pushed away the comforts of something familiar, told my naysayers to bugger off, and jumped (OK, sometimes I tiptoed) into a realm that felt foreign and scary. I don’t want her to be able to count those times on one hand. If she asks what I think about doing something seemingly crazy (not hitch-hiking-to-Vegas crazy, of course), I’m determined to give her the liberty to be daring.

I want her to recognize beauty in herself, especially because girls don’t often hear that boldness and honesty are all that attractive in women. I hope she identifies the futile pursuit of prettiness, with its convoluted rules and layers of lipgloss, as a waste of time and instead feels beautiful because she’s pursuing life on her terms. And maybe giving her the knowledge that beauty is not something elusive, owned exclusively by a few genetically gifted women, will mean she’ll be able to be nicer to herself; that she’ll be able to hush the dogged voice that’s inside each of us and is so adept at reducing our marvelous bodies to a collection of flaws. And yes, I’ll tell her she’s beautiful. Because she will be.

I want her to acknowledge and verbalize her feelings, even if she thinks they might rankle someone else. When someone in her life rolls his eyes at her fervor or belittles her heartbreak or tramples on her ideas, I don’t want her to close her eyes and shut her mouth. I’ve swallowed hurt or pretended I’m not disappointed because of the nagging ache not to burden or confront others. Perhaps telling her about my sadness or frustration on occasion will help her see that girls don’t always have to be happy or satisfied (or pretend to be). And may she read this essay in 13 years and be perplexed about why her mom would’ve ever bothered to please an offensive lady at a fish counter.

There’s more, of course. I want her to feel free to be silly and messy and rowdy and loud if she wants to be. I want her to be able to solve her own problems, even when I could fix them easily. Most of all, I want her to know that she’s never too difficult or too complicated to be loved.

So those strangers were right: Raising a daughter is challenging, but not for the reasons they think. Being my daughter’s mom is hard work because by her existence, she begs me to be bolder and more thoughtful about my life and hers. And I wouldn’t trade that for all the niceness in the world.

I Walk the Line

Three weeks into life as a working mom, I’ve become hyper aware of why there’s such fierce debate about staying at home with the kids versus being a working parent. This is a look at my new typical day. By Lindsey R. McKissick

6 a.m. The alarm is ringing, but I don’t want to get up. Gwynn is still asleep. If I were not so keen to go to work in downtown Denver, I could be, too. Instead, I have to shower, get dressed, and watch the clock so I can leave my Highlands Ranch house by 7:15. I used to leave for work at 8:15 when we lived in LoHi, but we recently moved to the ’burbs. Good schools and a bigger yard, yes—but also one helluva commute.

6:45 a.m. I’m all ready for a workday that doesn’t officially start for more than two hours. But, as I peek in to rouse my still-sleeping three-month-old, my willpower is tested. It would be so easy to spend the day with this baby nestled in my arms.

7:15 a.m. I whisk Gwynn out the door to the sitter’s or to my mom’s, along with the ridiculous amount of luggage that is somehow necessary for a day spent outside the house and apart. For a moment, I look at the sheer amount of stuff and think: This cannot be worth the hassle.

7:30 a.m. I have to leave her. My body aches at leaving my child with another person for nine hours. The pang is exacerbated by the fact that I could stay at home if I were a freelance writer instead of a staffer. If I didn’t go to an office, Gwynn and I could read, play on the floor, and take walks in the sunshine. Instead, I give her a quick kiss on the forehead, whisper “I love you,” and leave. I know I need the creative outlet work provides.

7:55 a.m. The bus is late, which means I won’t make my light rail train and I’ll likely be late for work. I’m schlepping a messenger bag of work stuff, a lunch bag, a bag of containers to “collect” Gwynn’s next meal, and a mug of hot tea to enjoy during the 30-minute ride into downtown. I feel like I’ve already put in a full day by the time I get on the train.

9:12 a.m. I’m late for work, but I’m finally here. My small cubicle, cramped as it may be, feels liberating.

10 a.m. As I sit in a meeting, I think about my afternoon interview and story deadlines. I feel a slight thrill at the thought of actually having a deadline. Three months at home with Gwynn made me realize the unstructured days begin to melt into each other. I’m happy to once again be part of the process that imagines 5280 each month.

11:30 a.m. I’m just hitting my stride on a piece of writing when I look at the clock: time to pump. No matter how you spin it, the process of using a breast pump is easily the most awkward (OK, humiliating) part of the working-mom business.

Noon My phone chimes and I see a picture of my baby up from her morning nap. I’m quickly saddled with the “It’s not fair you get to hang with my kid” feeling.

12:15 p.m. I get 20 uninterrupted minutes to eat my lunch and sit down with a glass of water. It’s magical.

1 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. I am lost in writing and editing. I relish the sensation of being me, the old me; just for a short time, I’m once again Lindsey the journalist, not Lindsey the mom, who struggled to squeeze in a shower yesterday.

4:35 p.m. I miss Gwynn.

5:47 p.m. My bus is 15 minutes late. This is wasted time. I feel cheated. Gwynn will be heading to bed in less than two hours.

6:10 p.m. When I finally poke my head inside the door at home, I don’t care if Gwynn is giggling at a toy or having a full-scale meltdown, I want to scoop her up in my arms and never leave her again.

10 p.m. From the monitor, I can hear only the sounds of Gwynn’s noise machine. No squawking baby sounds. I kiss my husband goodnight and then set my alarm.

State of Play

Twenty years ago, mothers faced sharper criticism than their male peers for taking risks in the outdoors. How far have extreme sports come from that double standard? By Kasey Cordell

On August 13, 1995, just three months after becoming the first woman and the second person to climb Everest alone, unsupported, and without supplemental oxygen, British climbing phenom Alison Hargreaves died while descending from the summit of Pakistan’s K2. The mountaineering world lost one of its brightest stars; Kate and Tom Hargreaves, just four and six, lost their mother.

After the shock of Hargreaves’ death subsided, the press latched on to the motherhood storyline. In numerous articles, Hargreaves was criticized for pursuing a high-risk passion while having two small children at home. Equal criticism, though, was not leveled at fathers on the same mountains, including two British men who died just days before Hargreaves on a nearby peak.

Seventeen years later, in May 2012, Telluride ski mountaineer Hilaree O’Neill’s children were nearly the same ages as Hargreaves’ when O’Neill stood atop Everest and then, less than 24 hours later, on top of neighboring 27,940-foot Lhotse, becoming perhaps the first woman to conquer both peaks in one day. Happily, O’Neill made it home safely, but if she had not, her family likely would have been spared any posthumous criticism. O’Neill says she sees little evidence of the double standard that existed for mothers in Hargreaves’ era today. “There’s not a lot of discrimination now,” she says. “I think we’re kind of past that.”

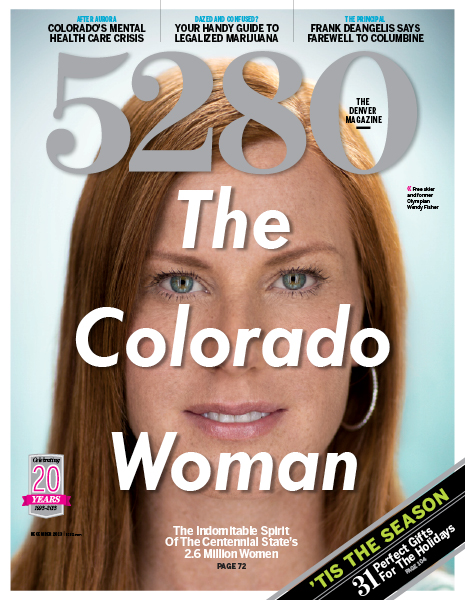

She’s not alone in the observation. Fellow marquee Colorado athletes also note such blatant injustice has largely dissolved from extreme sports—among them 27-year-old Boulder native and six-time national climbing champion Emily Harrington and Mt. Crested Butte’s former Olympic ski racer turned free skier, 42-year-old Wendy Fisher. But why?

The simplest explanation is more women are participating in sports—extreme and otherwise. As the number of female athletes has increased, so has society’s acceptance of what is “normal” behavior for women—and mothers. When Hargreaves was climbing, she was an almost singular example of a woman achieving extraordinary success in the mountains, making her the subject of fierce public celebration (and scrutiny). Thus, as British research fellow Paul Gilchrist noted in the May 2007 issue of Media, Culture & Society, Hargreaves became the focal point for a discussion of morphing values. Her accident occurred in the 1990s, a time—especially in conservative Britain—when society’s acceptance of mothers returning to work full time was just taking root on a larger scale, never mind mothers working in dangerous fields.

Such thinking might seem foreign to a generation of American women raised in the warm embrace of Title IX—and especially here in Colorado, which in many ways has led the way with respect to women’s rights: We gave women the right to vote in 1893, and in 1972, we added the Equality of the Sexes amendment to our constitution, something the nation has yet to do.

Plus, anecdotally, Colorado has one of the nation’s largest populations of outdoor athletes, many at the top of their fields. “We’re such a tight-knit group. Everyone’s in it to see the sport progress,” Fisher says of the free-skiing community. “When you show you’re talented, responsible, and hardworking, no one judges you for being a female.”

Still, female extreme athletes are not immune to the gender-equality issues prevalent in other industries: O’Neill points to pay equity and Fisher to the eternal to-work-or-not-to-work question for moms. “Women have come a long way in every realm, but there’s obviously still going to be hurdles for us to deal with,” says Harrington. “Maybe with adventure sports it’s different because we don’t allow the same cultural pressure to influence us as much. We’ve already rejected a lot of what society tells us is the proper way to exist in this world.”

Dana Crawford’s Universe

An abridged guide to the places Denver’s preeminent historic preservationist can call her legacy.

With all due respect to Governor John Hickenlooper, when it comes to getting credit for “creating” LoDo, the Gov has nothing on Denver grande dame Dana Crawford. Since saving Larimer Square from bulldozers in 1965, the pioneering Crawford has redeveloped more than 1 million square feet of the city, including the Oxford Hotel, Prospect Park, and the Flour Mill Lofts. “I had an entrepreneurial spirit, and Denver was welcoming of that,” Crawford says of her arrival in Denver in the 1950s. “And I was attracted to all the things people said could not be done.” Like the revival of Union Station as the vibrant heart of the city—a project Crawford grabbed hold of decades ago and hung onto “like a stupid bulldog.” The new, improved Union Station debuts next year as an elegant transportation hub accompanied by several restaurants and a hotel named in her honor. We offer a look at some of the less-well-known places that make up the complicated constellation of Crawford’s Mile High contributions.

Denver Public Library Together with Tattered Cover Book Store owner Joyce Meskis and CSU English professor David Milofsky, Crawford created the Evil Companions Literary Award and event, which has benefitted the Denver Public Library since 2004.

Victoriana Antique & Fine Jewelry

This early Larimer Square shop was started by Crawford.

Parade of Lights

Along with others, Crawford helped come up with the concept for nighttime floats as part of the Downtown Denver Improvement Association way back in 1975.

The ’Burbs

Crawford has consulted on master plans for Commerce City, Broomfield, Arvada, and Frederick, a northern outpost along Highway 52.

Pat’s Denver’s beloved purveyor of delicious Philly cheesesteaks resides in the bottom of Market Center, another LoDo building Crawford developed.

Edbrooke Lofts

In 1974, Crawford joined a team of investors that transformed New Orleans’ 1907 Federal Fiber Mills building into high-end condos. Sixteen years later, she brought the concept to Denver with the Edbrooke Lofts.

Coors Field

Recent Rockies retiree Todd Helton can thank Crawford, in part, for the view from first base; she served on a special committee for the design of the field.

The 80202

Many LoDo loft residents have a place to put out their welcome mats because of Crawford. Since 1990, she has helped build, fund, or plan the following buildings: Edbrooke Lofts, Acme Lofts, Flour Mill Lofts, and Ajax Lofts.

The Market

When Larimer Square didn’t have businesses to fill its vacant spaces, Crawford started her own, such as the Market. Until she sold it in the early ’80s, Crawford was in the odd position of being both tenant and landlord of this popular Larimer Square lunch spot.

Metro State, Community college of Denver, and CU Denver

When the state built the Auraria campus in 1977, it failed to include a budget for landscaping—an oversight Crawford remedied by securing a grant for improving the grounds through the National Endowment for the Arts’ City Edges program.

The South Platte

Crawford has supported Denver’s Greenway Foundation’s efforts to turn the city’s signature river from a hazmat zone to something that’s, well, a little less gross for 39 years.

The Cabaret

Crawford established this theater in the space where the current Comedy Works lives at the corner of 15th and Larimer streets.

From Where She Sits

As the governor’s chief of staff, Roxane White is responsible for the daily operations of the state of Colorado, including 30,000 employees and a $20 billion budget. Her ability to juggle all that’s involved in running the Centennial State is inspiring not because she’s good at it (which she is), but because she’s able to keep it all in perspective. By Lindsey B. Koehler

The restricted-access parking surrounding the Capitol is still mostly empty as Roxane White pulls her gray SUV into a space. It’s 7:55 a.m. on a sunny July day, and although many Denverites are just finishing their last cups of coffee before heading to the office, White has been up and working for more than two hours. Her day planner says she has eight meetings today, not including the breakfast appointment she just finished at Racines.

As soon as her black pumps meet the pavement, she’s in motion. Although Rox, as most everyone calls her, is barely five feet tall, the 49-year-old with strawberry blond hair and a dusting of freckles covers ground with surprising speed. White knows she only has 35 minutes before the senior staff meeting, and she wants to tick through some of the nearly 700 emails she receives each day before then. With her BlackBerry glued to one hand and a cup of decaf coffee gripped in the other, she quicksteps toward an employee entrance. Her pace slows ever so slightly when she first sees him. She tries mightily to ignore him. But then, because she can’t help herself, she stops completely and leans over to pat the head of a rust-colored golden retriever.

Anyone but White would’ve recognized the stopover as a rookie move. People who hover around the Capitol, cute dog in tow or not, often are looking to speak with someone “official.” Such is the case with Lee Somerstein, a 60-something blogger and author who’s driving across the country gathering stories about how the Great Recession has affected Americans. He wants to speak with the governor. He has left 15 messages and received zero response.

Somerstein has some leftover breakfast in his graying beard, and he’s overeager to talk to someone, but White doesn’t try to escape. Instead, she asks a perceptive question—How did the recession affect you, Lee?—and then actually listens to his tale of woe before telling him she has to run.

Which she does. She’s down to 20 minutes now. After hitting the ladies room and pouring herself another cup of decaf, White strides into the staff meeting, where she gets updates from her department heads about everything from Colorado’s medical marijuana dispensaries to the upcoming National Governors Association conference to ongoing issues within the state’s Department of Corrections. For one of the final updates, a staffer reports that Capitol security is aware of “the weird guy with the dog, who’s harassing people.” White, who just seconds before had been laughing with her colleagues and even shot her deputy chief of staff friendly double-barreled middle fingers during the 40-minute meeting, bristles at the idea that Somerstein and his dog, Trooper, are a menace. “He was just talking to people about the recession, about how it ruined his life,” she says with a hint of admonition. “I like talking to people like him. It gives me perspective.”

The thing about Roxane White is that few people have a perspective like hers. On the wall above her desk hangs a small wooden sign with a W-?, which read from right to left spells out the brand—open diamond bar W—from the ranch she grew up on in the rural town of Victor, Montana. On a shelf along the wall there is a picture of her daughter, Donalyn, her stepson, Zach, and her foster son, Daniel, whom she raised for many years as a de facto single mother. On a piece of paper taped just above her computer there is a saying by Gifford Pinchot, who was a governor of Pennsylvania in the 1920s and ’30s: “It is a greater thing to be a good citizen than to be a good Republican or a good Democrat.” And on her right leg, there is a tattoo that reads “The needs of the poor take priority over the desires of the rich,” a quote from Pope John Paul II.

White says she needs these visual reminders to keep her centered, but it’s clear to anyone who meets her that she needs little assistance remembering what’s important to her (work, her kids, her friends, God, the homeless) and what is not (romantic relationships, partisan agendas). It’s a personality trait that has served her well professionally, taking her from working as the executive director of a youth services center in San Francisco to being the president of Urban Peak, a Denver nonprofit that helps kids experiencing homelessness, to heading up the Denver Department of Human Services to being then-Mayor John Hickenlooper’s chief of staff to today serving in the same role in the governor’s office—in just 17 years. Her dramatic rise is all the more poignant for its relative improbability: Although White had what she calls an idyllic early childhood, financial hardship brought on by family tragedy—a couple of strokes that partially disabled her mother when White was nine, and the unexpected death of her father when she was 13—could have stifled her ability and drive to leave Victor. She had the highest grades in her small high school class, but an undergraduate degree from Lewis & Clark College in religious studies with a minor in Judaism and master’s degrees in divinity and social work would have been unfeasible without the hefty scholarships White worked tirelessly to earn.

Sitting on a hot pink exercise ball, shoes under her desk, bare feet gripping the plastic orb, White still has the affect of an earnest teenager studying for an exam. Except it’s not an algebra test she’s prepping for; her next meeting is a daily check-in with John Hickenlooper. As the governor’s chief of staff, one of only 10 females to hold that position in the United States, White’s monumental job can be distilled to this concise description: “I handle the day-to-day functions of the state government so that John can focus on vision and strategy,” White says. “If I’m doing my job right, what takes eight hours of my time to figure out should then only take 15 minutes of his time to make an informed decision.”

Over a salad delivered to a massive conference table in Hickenlooper’s office, White and the governor discuss the day’s happenings in what sounds like another language. They bandy acronyms and last names and policy measures while finishing each other’s sentences and chuckling at things only they understand. The two clearly have an affinity and respect for each other; it’s a kinship that has more of a sibling vibe than the romantic relationship White says people so often (and so infuriatingly) infer. In fact, White says that persistent allegation—sometimes subtle and sometimes not—is one of the most disappointing aspects of being a woman in a leadership role. The blatant sexism is also, in her opinion, partly why more women aren’t in politics. “Men don’t consider women for positions because of the perception,” she says, “and women don’t like it that people think they’re sleeping their way to the top.”

The governor, however, originally considered White for the mayor’s chief of staff job, he says, because she was “orders of magnitude” more qualified than the other candidates. Plus, he says, he liked her spark. Today, Hickenlooper relies on White to tell him the no-bullshit truth, even when she knows he’s not going to like it. He admires her energy, her nonpartisan mentality (she’s a registered independent), her thorough preparation and attention to detail, and, maybe more than anything, what he says is an inner joy she radiates. For her part, White cites a long list of reasons why she happily works at least 75 hours a week for Hickenlooper, not the least of which is that she knows in her gut he didn’t even think about the fact that she is a woman when he hired her.

After they finish talking politics, White reminds the governor this is their last appointment before they both head off on vacation—simultaneously. White is primarily concerned about what happens if. As in, what happens if there’s another Aurora shooting? Or what happens if more wild fires break out? Or what happens if another little girl like Jessica Ridgeway goes missing? White wants well-defined instructions left behind in their absences in the event what if would happen again. With a mouth full of salad, the governor shrugs and says he’ll just come home from the East Coast if disaster strikes. White, who is planning to visit her 20-year-old daughter Donalyn in Uganda for two weeks, is not comforted by his easy solution. She’s worried the governor’s signature could be immediately necessary and wants to make sure everyone who will be at the Capitol in his absence knows exactly who would step in and how that would get done. Again the governor shrugs, this time as if to say he’s well aware of—and values—the fact that White will handle the particulars of this even though he thinks it’s unnecessary.

Everyone who knows Rox knows that she powers down at 9 p.m. So when her cell rang around 8:45 p.m. on March 19, 2013, White knew it must be important. The caller, a Colorado Department of Corrections staffer, told White that Lisa Clements needed White to call her immediately. It wasn’t unusual that Lisa would call, but White wondered why her friend hadn’t just called her directly. When Lisa’s shattered voice dissolved through the earpiece seconds later, White had her answer. Just minutes before, someone had rung Tom and Lisa Clements’ doorbell at their home in Monument. Tom, who had been the executive director of Colorado’s Department of Corrections for more than two years, opened the door and took a bullet in the chest. White had been close with Tom and was one of the first people Lisa called that night after dialing 911.

White was devastated. She had been in the Clements’ home enough times that she could easily visualize exactly where her friend and colleague died that night. But unlike after her father had died and her mother threw occasional Friday afternoon “pity parties”—in which White, her older sister, and her mom allowed themselves exactly 30 minutes to cry while eating popcorn and drinking homemade wine—White didn’t have a half hour to grieve. She told Lisa she would get there as fast as she could, she called the governor, and then she had to make sure the other 17 Cabinet members didn’t hear about Clements’ death from the local nightly news.

During the days that followed, at a time when no one in the Cabinet should’ve had to be functional, White did what she does so well—she managed the small details that were more essential than they initially appeared, and she took care of her people. “There is no one in the history of the chief of staff position that was more suited to dealing with that situation,” says Mike King, the executive director of the Department of Natural Resources. “With her background in social work and divinity, she was so good at knowing when to step into an alcove and give someone a hug.”

White probably needed the embraces as much as anyone. A week after Clements’ death and just days after authorities in Texas shot and killed Evan Ebel, a recent Colorado parolee with possible gang ties who had likely murdered Clements, White agreed to be the interim head of corrections. “We were uncertain what had happened, and we wanted to ensure our staff members felt, and were, safe,” White says. “Normally, a deputy would have been elevated. In this case, the governor and I felt it was important to be more hands-on.” For White, assuming that position meant shouldering enormous risk: If Ebel had been working with other gang members—as some people believed he had—there was no telling who might have been the next target.

For weeks, White relied on her faith to get through the long, sometimes scary days. As an ordained minister, she took comfort in the belief that she was not alone. And when she felt like she couldn’t cope with the stress any longer, White asked God to let her see the bigger picture. Sometimes, even for Roxane White, finding perspective means having to ask for help. In mid-April, the governor announced that Roger Werholtz, a retired prisons chief from Kansas, would take over for White. She was relieved but not exempt from worry: Werholtz’s safety as the interim director (and now Rick Raemisch’s, as Clements’ permanent replacement) was something she prayed for every day.

Just 49 days after white had spoken with the governor about being ready for what if, it happens. White is at a 9/11 commemorative event when her phone blows up. Texts, calls, emails—they ding in one after another. The rain, which had begun falling across the state two days earlier on September 9, was not stopping. Boulder County had already received 4.24 inches, while Weld and Jefferson counties had been soaked with more than five. The information coming into White’s BlackBerry alerts her that these areas and others are expecting another five to 15 inches of precipitation in the next 72 hours.

By midnight Wednesday, White is finished with her calls to the Colorado Office of Emergency Management and is authorizing the use of the Colorado National Guard. At 3 a.m. Thursday, White informs the governor about the possible need to contact the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). For the next few hours, White is on standby to sign FEMA paperwork, but in the meantime, she gets ahold of Cabinet members. She phones King at the Department of Natural Resources to talk about Colorado’s dams. She converses with Karin McGowan at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment about potential wastewater issues. At 8:30 a.m., White clears her entire day and begins figuring out how the state will fund the rescue and recovery from what are becoming floods of biblical proportions. The daily burn rate for the deluge will be about $3 million. To cover the cost, White will borrow from the controlled maintenance budget, use FEMA advances, and dip into the state’s water reserve fund.

Helping with the relocation of Hurricane Katrina refugees to Denver and working through the wildfires over the past two summers have given White experience with managing the fallout from natural disasters. She has learned the command structure and understands how to file the correct paperwork—experience that’s critically important in getting the right kind of help to the right places. But White has also learned that natural disasters like these are all about people; people who were OK yesterday and are shattered today. And White has a lot of experience with that, too.

White attributes her lifelong soft spot for those experiencing homelessness to the lessons she learned in the weeks, months, and years that followed her father’s death. Before he died, the White family had lived well, taking family trips and wanting for very little. After he died, money became tight and cross-country trips disappeared. Even as a teenager, White could feel the uncertainty creep in. It was a painful way to learn that life doesn’t always adhere to the notion that those who do what they’re supposed to do, who do everything right, will always have a smooth road to follow.

Surveying the damage around Boulder from a helicopter on Friday, September 13, White doesn’t just see washed-out streets, wobbly bridges, and waterlogged homes; she sees thousands of people who had a place to sleep yesterday but don’t today. “Rox is no-nonsense, organized, and can be very intimidating,” says Alan Salazar, the governor’s chief strategy officer and director of the Office of Policy, Research and Legislative Affairs, “but she’s a chocolate drop when it comes to people. It’s rare to find someone who can bring the hammer and the handkerchief effectively.”

It’s also uncommon to find someone who is so willing to give up so much of her personal life for her professional life. During the floods, White worked 18- to 20-hour days for seven days straight. She was glad to. And she’s more than accustomed to it.

Throughout her career, White has rarely held a job that didn’t require a commitment of more than the standard 40 hours a week. There were many nights when White would carry Donalyn to the car to go handle a crisis at a shelter she ran or when she would miss a dinner date with her husband or best friend. White knows she made sacrifices and forced those around her—including her kids and two ex-husbands—to make them with her. But unlike so many people, particularly women, White doesn’t strive for that balance so often mentioned in books and magazine articles. She believes “balance” is an overused word. Instead, she looks for what makes her soul sing, for what makes her happy, for what makes work feel like play. “People look at my calendar and they say it’s not at all balanced,” White says, “but my God, I have a fabulous life. I’m happy, I love my kids, I love my work, and I don’t question whether or not it has value.”

In The Line Of Fire

When the state Legislature’s female leadership took on gun control in early 2013, everyone knew the debate would be red-hot. But no one predicted the sexism and violent threats that would be fired at some of Colorado’s most powerful women on their way to victory. By Megan Feldman

Editor’s Note: This article contains strong language and may be offensive to some readers.

It had been a long day. Heck, it had already been a long month—and it was only the fifth day of March. But Evie Hudak knew she should check her email one more time before she turned in. Hudak, the state senator from Colorado’s District 19, opened her laptop and perused the list of unopened emails. One looked unfamiliar. It was from someone named David and had no subject line. She clicked on it.

I am going to stick a knife up your cunt and tear your heart out through there. If you have one.

Hudak physically recoiled at the message, but she continued reading.

You’re a fucking disgusting piece of shit, and you deserve to be gang raped until your guts fall out of your rotten old cunt, you worthless sack of shit. Go fucking die.

As she read the words, she knew this was not a bad joke or spam. The person had very intentionally sent these vile sentences to her. Although the email had not said why David was so angry, Hudak knew. During a legislative session the day before, she had been speaking in support of a proposed bill to ban concealed-carry weapons on college campuses. A rape survivor testifying against the bill said she would have perhaps not been victimized had she been carrying a firearm. Hudak had countered that statistics didn’t support the likelihood of prevailing over an assailant while armed. Her remark hadn’t been well received at the time—and it was clearly still inciting a negative response. Hudak closed the laptop, slipped into bed, and tried not to cry as she lay next to her husband. She reminded herself: As a politician, she was supposed to have thick skin.

Hudak, 62, did her best to brush off David’s email as she drove to the Capitol the next morning. She’d decided she couldn’t let one foul-mouthed wacko bother her so much. But when she got to her desk and opened her email, there were more:

From DW: Listen up you cunt fucking whore, You need to be gang raped, you cunt fucking whore!!!!!!!!!!

The messages—both phone calls and emails—piled up throughout the day, including one note that called her a “stinking fat nasty dike.” That night, she cried herself to sleep.

After the mass shootings in Aurora and Newtown in 2012, the national gun-control debate exploded. In Colorado, where residents had suffered through two horrific massacres in 14 years, the discussion was particularly heated. In early January, state Representative Rhonda Fields announced she would seek to pass new restrictions on guns, and she began to host stakeholder meetings with gun-violence victims, law enforcement representatives, and gun-control advocates. The movement gained momentum from there, and by the end of February, legislators were running seven gun-control bills—all of which were sponsored or co-sponsored by women, including Hudak. If passed, the proposed bills would have banned high-capacity magazines; required background checks for private and online gun purchases; added liability for sellers and owners; banned legally concealed weapons on college campuses; eliminated online gun training; mandated that gun purchasers pay for background checks; and expanded the ban on weapons for domestic violence offenders.

Within weeks of announcing the legislation, the bills’ sponsors—both male and female—and their aides noticed a spike in the amount of feedback they were receiving from constituents. But they also noticed a difference in the responses: Those directed at the female gun-control bill sponsors had a distinctly violent and anti-female sentiment. “I got called ‘slut,’ ‘bitch,’ ‘whore,’ and ‘stupid,’ and ‘I hope you get raped’ was a repeated phrase,” says state Senate President-elect Morgan Carroll. “I started seeing threats of physical and sexual violence, and some direct and indirect threats like, ‘I have a gun, and I’m not afraid to use it.’ After Gabby Giffords, we have to take that seriously.”

Hudak received such a surge of vicious, sexually explicit, demeaning emails that her staffers created a folder labeled “Threatening” and filtered them from her inbox using key words such as “whore,” “bitch,” and “cunt.” The senator agreed it was unproductive to read any more of the messages. She had already spilled too many tears over them. Plus, she believed in the legislation, and nothing in those emails was going to change that.

Senate staffers may have shielded their bosses from the flow of hostile mail, but the need to do so was troubling. While the majority of the messages were standard fare, the fact that an extreme and vocal faction felt comfortable using sexist insults and threats of sexual violence to try to influence public officials raised important questions: At forty-one percent, Colorado boasts the highest percentage of female state legislators in the nation, but what does it mean that they’re experiencing this level of gender-based vitriol? Can this type of menacing have a chilling effect on American democracy? As Carroll puts it: “Who’s going to be willing to serve if, when you need to debate a policy issue, you’re going to subject yourself or your family to threats of violence?”

Some social scientists theorize that as women occupy more leadership posts around the world, a certain slice of the male population is launching a backlash. “There’s a perception out there that women are taking over, and, especially among extremely conservative men, that can raise concerns about masculinity,” says Nancy Ehrenreich, who teaches a class on race, class, and reproductive rights at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law. “Any group, when it perceives a threat to its power, can get angry.” Sexual epithets and threats of rape have long been common strategies used to hold power over women. Yet sending sexually explicit, threatening emails to female politicians—or shooting them, in the case of Giffords—is obviously not representative of the actions of men, broadly speaking, Ehrenreich says. It is representative of how, in a few men, broader cultural trends “get turned into something really extreme because of their own personal dynamics.”

The hate mail endured by many of Colorado’s female legislators during the 2013 session echoes threats fired at female activists in developing countries such as India. In that country in 2012, a prominent women’s activist was threatened with rape by someone using the handle @RAPIST during an online chat about violence against women, and a well-known journalist stopped tweeting about rape when someone tweeted her daughter’s age and classroom location. “I’ve met women [working in politics] from places like Egypt, and they’ve always talked about threats of rape and physical violence as one of the hurdles [for women in political positions], but that didn’t really happen here,” says Faith Winter, 33, Westminster mayor pro tem and executive director of Emerge Colorado, a nonprofit that trains women to run for political office. “Now, it’s something to think about.”

Fields experienced the backlash against female leaders firsthand in February. As the House debated the gun measures, Fields, who was elected to represent Aurora in 2010—five years after her son was shot to death before he was due to testify in a murder trial—was checking her email during a break. She opened a message that turned her stomach. It addressed her as “Hey Nigger Cunt,” then added that both she and fellow gun-control legislation sponsor state Representative Beth McCann needed “a good fucking” and he hoped someone would “Giffords” them. She showed the note to McCann, they both shook their heads in disgust, and they did their best to put it behind them. But within days, a member of the Colorado State Patrol asked to speak with Fields: The officer showed her a letter that had been intercepted by an aide. The author claimed he knew where Fields lived and mentioned her daughter by name. “I keep my 30 Round Magazines There Will Be Blood! I’m Coming For You!” it read.

This time, Fields was afraid. “I’d already lost a son,” she says. “You’re calling me the N-word and the C-word and mentioning my daughter? My son was threatened before he was killed, and he dismissed it. I could no longer dismiss it.” Police tracked the message to Franklin Sain, a 42-year-old IT executive from Colorado Springs, who was arrested and charged with harassment involving ethnic intimidation and attempting to influence a public servant. Five months later, in July, Fields dropped the charges against Sain, saying she didn’t feel prosecution was necessary because the harassment had stopped and the gun-control laws had passed.

Observers who read about Sain’s threats in the newspapers may have been tempted to write him off as a lone extremist, but he wasn’t the only one to use sexually explicit words and intimidation tactics. One nonpartisan staffer told Carroll that while she was helping witnesses testify during a March hearing, a male opponent of the bills shouted at her to, “Shut up and sit down!” Annmarie Jensen, an independent lobbyist who represents the Colorado Coalition Against Domestic Violence, said that later, after hosting an event to support legislators targeted by a recall effort resulting from their pro-gun-control votes, she received an anonymous call from someone who said Jensen’s home address had been posted on the “Rants & Raves” section of Craigslist in an attempt to goad opponents to arrive on her doorstep. And around the same time that Fields received the threats from Sain, gun-rights advocate Nick Andrasik—who went on to become the spokesman for the recall effort aimed at state Senators John Morse and Angela Giron—posted online comments in which he called Fields “a vacuous cunt” and state Representative Brittany Pettersen a “stunning cunt.” (Andrasik later apologized, saying the statements “in no way” represented the opinions of the recall supporters. He was later replaced as spokesperson.)

Andrasik’s online comments highlight the difference between the vitriol directed at male and female lawmakers during the gun debate: He called state Representative Joe Salazar a “fucking retard,” which, despite being a despicable and offensive term, is not sexually explicit or gender specific. Morse, an advocate for gun control and a sponsor of one of the bills, was never threatened with violence. Speaker of the House Mark Ferrandino says the hate mail the female legislators received tended to be more personal than that sent to the male legislators. “I got plenty of nasty emails,” Ferrandino says, “but nothing to the level that Representative Fields got.”

In fact, only one male legislator reported a threat of sexual violence during the gun-control discussions in Colorado: State Senator Jessie Ulibarri, from District 21, received a call from someone who said they hoped his two-year-old daughter would be raped.

These acerbic anti-female campaigns might feel less disturbing if they were isolated to a single issue, like gun control. But they’re not. This past summer, an obscure political action committee dedicated to defeating Hillary Clinton as a 2016 presidential candidate launched an online game called “Slap Hillary,” in which players were instructed to smack a caricature of Clinton clad in a pink pantsuit. Around the same time, Texas state Senator Wendy Davis made headlines by filibustering an abortion measure and was derided by opponents as “The Abortion Barbie,” a not-so-subtle reference to her appearance. None of this is surprising to McCann, a former prosecutor and onetime manager of public safety for the city of Denver. Years ago, as she was trying to make the firefighter application process more amendable to women, someone mailed her a dead fish with a bullet in its eye. The accompanying note read that women “should stay in the bedroom and the kitchen.”

While caustic incidents are taking place across the political landscape, there’s no denying gun control incites amplified rhetoric. Ehrenreich says there could be a cultural reason why certain men waged such a venomous crusade against the women pushing gun regulations: The issue highlights cultural links between guns and traditional concepts of masculinity. “Guns in our society are associated with virility and strength,” she says, and a part of traditional gender roles involves men being stronger than women. The prospect of having the right to guns circumscribed by women, Ehrenreich says, can be seen as a humiliating defeat and a sign of “failed masculinity” that leads to intimidation.