The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

The spring day had been a warm one, but as Taylor Romero walked from his Centennial office across the parking lot to the Embassy Suites, the sun was setting and the air chilled. His employer, Wayde McKelvy, had been holed up in a room at the hotel for days. Romero knew this likely meant one thing—well, two things: booze and hookers. For as long as Romero had known McKelvy the guy exhibited hedonistic, self-destructive tendencies. Lately, though, he’d been on a Charlie Sheen–like tear. The 46-year-old McKelvy had taken to showing up at work drunk, holding the waist of whichever working girl he’d flown in. He was so blatant that even his wife, the mother of their twin girls, knew about it all. By then, late spring 2009, Donna McKelvy had grown accustomed to her husband and his prostitutes. What she could not abide, however, was the whore du jour banging up the Mercedes-Benz. She’d asked Romero to go to the Embassy and get the keys.

Romero took the elevator up and knocked. The way he remembered it, the door opened, and there, standing on a floor littered with empty Bud Light bottles, was McKelvy. The two men were not merely colleagues, they were friends. They plopped onto a couch, McKelvy dropping his 6-foot-4-inch, 250-pound frame. Romero learned the keys to the Benz were gone. And sure enough, so was the girl. While Romero stuck around, waiting, the two men discussed their dream of making a movie together. It would be dark and atmospheric; McKelvy already picked a tagline: What’s the Definition of Insanity?

Young with long dark hair, Romero is the kind of computer-programmer dude who wears flip-flops to work. He’d built a website for the Mantria Corporation, a new green company for which McKelvy was the lead investment broker and ultimately the sole money engine. This startup, as McKelvy had put it to anyone who’d listen, was a revolutionary investment opportunity. Mantria, so went the pitch to investors, was constructing the country’s first carbon-negative residential community, where energy-efficient housing would be built with sustainable materials, and the whole thing would be powered by alternative energy. As if that weren’t enough, Mantria was also supposedly on the verge of releasing an unprecedented technology that turned garbage into usable materials and produced something called biochar, a charcoal that when used as a fertilizer was carbon-negative. Operating from his hometown of Denver, McKelvy would raise close to $40 million from hundreds of investors, the majority of them from Colorado.

After a while, a short Latina woman walked into the hotel room holding a bag of groceries and the car keys. Slurring, McKelvy yelled at Romero. Romero yelled back. Something about the family’s car and the prostitute. From a corner of the bottle-strewn room, the prostitute piped up: “Why are you talking about me like I’m not here!” She put down the keys, Romero grabbed them, and he split. Talk about the definition of insanity: “It was classic Wayde under pressure,” Romero says. “The bigger things get, the harder Wayde crashes.”

The crash had only just begun. In November 2009, some six months after that night in the hotel, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filed a civil lawsuit against McKelvy and his wife, and against the Philadelphia-based owners of Mantria. As far as the SEC was concerned, McKelvy had fleeced his investors out of tens of millions of dollars in a big, green Ponzi scheme.

Multimillion dollar white-collar scams are as American as apple pie. See, most recently, Bernie Madoff, who wormed his way into Wall Street and decimated the portfolios of thousands of investors to the tune of $17 billion. Sentenced to life in prison, Madoff has become the infamous face of financial-market malfeasance nationwide. Coloradans, meanwhile, witnessed their own high-profile grifter. Denver hedge fund manager Sean Mueller ripped off 65 people, including John Elway, for some $71 million. Last December, Mueller was sentenced to 40 years in prison. But whereas Madoff’s and Mueller’s frauds could have occurred anywhere, during almost any era, McKelvy and Mantria’s “business plan” was based on a uniquely contemporary premise, and one that has been especially appealing for Coloradans.

The United States shouldn’t be dependent on foreign oil; the country must create a workforce for the 21st century; the environment must be protected: These are a few of the reasons the federal government has been nudging industry toward green, or clean, energy. The national trend has dovetailed nicely with progressive thinking in Colorado, where conservation and sustainability are rooted in the mountain lifestyle. Former Governor Bill Ritter lured numerous clean-tech companies to Colorado, including the world’s largest wind turbine manufacturer, Vestas. He successfully championed a bill that required the state to produce 30 percent of its electricity from renewable energy, the largest proportion in the Western states.

Colorado is so synonymous with green power that in February 2009, President Obama chose to announce his $787 billion economic-stimulus package—filled with “clean-energy” provisions—in Denver. The venue the president chose was the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, where the roof is home to a solar-panel field, which was installed by a Boulder-based company, Namasté Solar. Indeed, one would be hard-pressed to imagine a place more perfect than Denver to exemplify the confluence of environmentalism and capitalism (not to mention the venture capitalism of Boulder). Arguably, no one is more primed for green investment opportunities—or susceptible to clean-energy con men—than Coloradans. “If you can show me how to save the world,” as a Denver-area woman who was one of the first Mantria investors puts it, “sign me up.”

It was just after Obama’s Denver appearance that McKelvy and his Philly-based Mantria partner, CEO Troy Wragg, were telling investors that the company was engaged in promising meetings with the president of Ivory Coast; that Mantria was hobnobbing with the Clinton Global Initiative; and that the company was “this close” to selling $240 million worth of its “systems.” To develop their audacious projects Wragg and McKelvy needed cash. Mantria investors, according to the SEC, were offered securities in the form of “promissory notes, stock, limited partnership interests, and so-called profits interest.” These contracts promised extraordinary returns over periods as short as eight months.

The reality, according to the SEC, was that Mantria produced virtually no revenue in its two years of operation. The purported $240 million deal vanished. Mantria’s product sales amounted to unloading one bag of biochar. It went for $97. The facts, so say the feds, show that every dime investors received was funded by new investors—in other words, a classic Ponzi scheme. McKelvy was not an employee or corporate officer of Mantria, but he was a rainmaker, persuading investors to empty their retirement accounts for the promise of 17 to “infinite” percent returns.

Since 2008, securities officials have targeted at least five alleged scams involving clean energy, prompting the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority to release an investor alert stating, “It seems like everybody’s going green these days—even fraudsters.” And according to the state and federal paper trail, Mantria is the biggest green scam to date in the United States: Investors lost some $35 million, more than all of the other green scams combined. In the SEC complaint, McKelvy is akin to the Madoff of green—with a touch of Tony Robbins. And there may be another similarity between McKelvy and Madoff, and, for that matter, the local Mueller crook: McKelvy appears to be another financial fraud halted too late due to regulatory bureaucracy.

Troy Wragg, a working-class kid from Philly turned scrappy entrepreneur, created Mantria in 2005 while in his early 20s. His espoused dream was that Mantria would develop a carbon-negative residential utopia. Big dreams from a relative nobody like Wragg needed capital. For about two years, he was in business with BridgePoint Ventures LLC, a Florida-based real estate management firm. Sometime around 2007, however, BridgePoint ended its partnership with Mantria. “We had a pretty unceremonious parting of ways,” says Edward dePasquale, a BridgePoint vice president. The way dePasquale explains it, Wragg’s Mantria was over-appraising real estate, and BridgePoint decided “that we didn’t want to deal with him in any way, shape, or form.” Fortunately for Wragg, one of BridgePoint’s affiliates, Wayde McKelvy, who ran an LLC called Speed of Wealth, saw an opportunity in Mantria, and that same year the two began working together.

The men complemented each other quite well. Wragg was a fast-talking, youthful city slicker from the East Coast; McKelvy, twice the kid’s age, was a rugged, charismatic Coloradan. He attended South High School, then the University of Northern Colorado, where he played offensive lineman on the football team and majored in business. According to three of McKelvy’s former UNC teammates, he was the champion of the freshman beer “chug-a-lug” contest; he had a “screw loose”; and he wasn’t above eating a handful of worms to get a laugh. Former teammate Don Barlass remembers that McKelvy “definitely enjoyed school, enjoyed football, and enjoyed life. If Wayde was around, you knew you’d be having fun.” None of McKelvy’s old pals would have pegged him as a guy to scam anyone. On Team Mantria, Wragg rattled off numbers and stats, whereas McKelvy talked about big-picture-type stuff, in rousing and sometimes blunt everyman language.

On calls with potential investors in spring 2008, the personalities of the new partnership clearly had found their rhetorical groove. The two men were soliciting funds for Mantria Financial LLC, set up ostensibly to finance purchases in the carbon-negative utopia. According to the pitch, this community, Legacy Ridge, in Dunlap, Tennessee, had everything. Ten miles of streams, 12 miles of bluff lines, a five-star restaurant, and two designer golf courses—all being built with sustainable materials and powered by alternative energy. Any investment, Wragg laid out, would earn 17 percent annually for the next two-and-a-half years, and then an additional half-percent equity stake in the company’s projected profits ($70 million) after another two-and-a-half years. The possibilities were astronomical. A $250,000 buy-in would bear a $456,250 profit.

Enter McKelvy: “What Troy and I know,” he said in his folksy Colorado baritone, “is that if we make you happy with your returns—and that’s our number one priority, by the way—that you will always invest with us and we will have an ongoing business.” No one on that call questioned McKelvy’s compensation package. He was pulling 12.5 percent off the top of every investment he brought in, which is a rate of commission double that of what is typical for a well-compensated financial broker. And although the SEC requires broker-dealers be licensed, McKelvy, along with Wragg, was not.

“For those of you waffling out there,” a caller on the teleconference said, “quit your waffling and get with the program. These guys know what they’re doing 110 percent.” Another caller added: “You can’t get a better education than from Wayde.”

In one of the calls, the former college football player sounded as if he were in a locker room at halftime, throwing down a gut-check challenge to his team: “A lot of things I hear out there. Number one: ‘It’s too good to be true.’ The first thing I say is, ‘Well then shouldn’t you jump in it right now?’ I’m sure you’ve heard that it’s too good to be true to get those kinds of returns in this market. Well folks, those of you who are invested with us know it’s not too good to be true. You get your checks. We keep coming out with better products.”

A stroll through The Venetian hotel and casino in Las Vegas is a walk of luxury. Marble pillars and gold-plated fixtures frame every hallway, painted murals adorn arched ceilings. Every turn seems to lead to the casino where you’re enticed to ooh and aah at the pretty possibilities; never mind the odds—bet big. It was here, at the Venetian, in December 2008, that Mantria investors gathered for what the partners described as a “big, end-of-year boot camp.”

They packed 100 to 200 strong into the ballroom, where projections of the Mantria logo—a large, oddly shaped M—were on every wall, looming over the audience. According to a handful of investors present for the gathering, McKelvy lurked in the back of the room while Wragg stood on stage in the spotlight. Mantria, he began, had undoubtedly delivered to investors unparalleled opportunities. None, however, were better than what he was about to present: What if you could help solve the climate crisis and eliminate the need for landfills? What would that look like for America? What about the world?

Well, after scouring the country, Wragg had discovered just such an opportunity. Mantria, he announced, was partnering with a company to develop technology that would produce biochar. What’s more, the technology would transform waste into usable products. It was a concept tailored for marketers. As Wragg repeated throughout his talk: “Trash into cash.” Romero, the computer programmer McKelvy had hired, noticed McKelvy standing at the back of Wragg’s presentation. To no one in particular, McKelvy repeatedly interjected his own version of the slogan he originally coined. “Shit into cash,” he kept saying. “Shit into cash.” Romero could tell that McKelvy was drunk.

After the presentation, audience members lined up to give video testimonials. “It’s been a mind-blowing experience,” one said. Another exclaimed, “I’m, like, having to take sleeping pills because I can’t sleep at night! Because I am so excited about what they’re talking about in our investment opportunities!”

Romero saw that McKelvy wasn’t as enthused. At dinner that first day, McKelvy appeared with a beer in hand, continuing to drink. Having seen his theatrics at Wragg’s speech, and now drinking into the late afternoon—Romero saw this as a possible sign of trouble. Romero was still in high school when a contact of his stepfather’s introduced him to McKelvy. It was the early 2000s, and McKelvy asked the kid to build a website for his wife’s insurance business. Romero jumped at the chance. Up to about 2003, he was paid well to develop the site. But then Romero watched McKelvy implode—drinking heavily and eventually filing for bankruptcy. Romero remembers McKelvy one day coming to him and saying, “Hey, we’re out of money.” Romero left for San Diego, where he remained until McKelvy wooed him back in 2008. Now, in Vegas, there was something in McKelvy’s demeanor; something of that old Wayde that Romero saw in the new Mantria Wayde.

Romero and other employees rode the strip of bright lights in stretch limos. At a VIP club, they were escorted past long lines into roped-off areas where, as Romero puts it, “top-shelf liquor is flowing like the nearby waterfall. It. Was. Crazy.” To employees like Romero, the party seemed a deserved celebration of the past year’s work and the future’s infinite possibilities. “We were going to save the planet,” Romero says, “and we were having a blast doing it.”

McKelvy didn’t attend the party on the strip. By the last day of the three-day boot camp, he was gone. He didn’t even show for his planned presentations. Outwardly, he had plenty of reasons to party and stick around. He had millions of reasons. He was becoming rich off of the commissions. He was well on his way to making $6 million over two-and-a-half years.

Business at Mantria boomed in the new year, 2009. The company was supposedly working on deals with New York and Colorado; the governments of Congo, West Africa, Liberia, Nigeria, and Ivory Coast; and with corporations like Cowboy Charcoal and John Deere. After standing on stage with Bill and Hillary Clinton in New York that year, Wragg employed what may have been stunningly transparent phrasing when he told investors, “It only adds another aura of credibility to what we’re doing.” McKelvy had already raised another $27 million.

Experts say Mantria’s technology could have achieved something similar to what was reported. But only with years of further tweaking. Hugh McLaughlin, the director of biocarbon research for Alterna BioCarbon in British Columbia, recalls witnessing Wragg tell a renewable energy conference that Mantria’s technology could generate biochar at a rate that would exceed scientific limits. Mantria’s promise, simply put, ridiculously outpaced reality. “Every fact about this thing,” McLaughlin says, “was exaggerated beyond any reasonable technical standards.” Yet only a few weeks after Vegas, during a January webinar with investors, McKelvy and Wragg projected a 53 percent annual return on a buy-in to the carbon-diversion systems.

Whatever melancholy—or was it pangs of conscience?—McKelvy might have been feeling in Vegas, was gone. Never mind the odds—bet big, was essentially what he told his investors: “I want you to go to your [401(k)] administrator tomorrow and ask them what it would take for you to roll out all your money. Don’t worry about anything they tell you. They’re going to try to frighten you. Don’t worry about that because [in] the mega-Webinar on February 10 I’m going to blow your mind.”

The mind-blower, investors learned on a teleconference, was that the U.S. Department of Agriculture was set to offer loan guarantees to Mantria, an FDIC-like endorsement backing investors’ money. A month later, in March 2009, Mantria announced a supposed letter of intent with the state of New York. But there were no deals with the Department of Agriculture and no letters of intent with any state governments.

That was right about the time McKelvy started living life as if he were the star of a Girls Gone Wild video. A source familiar with the McKelvy family says, “As soon as this guy smells money, he gets ready for alcohol and a bacchanalian orgy.” He also seemed to be the unhappiest man on the planet. McKelvy told Romero that he was being asked to raise more money than his original goal. McKelvy wanted investors to get their money back and to be done with this. But, he told Romero, “I’m at the point of no return.”

During this period, McKelvy’s bank account seemed as bipolar as his moods. Between January and September 2009, the account showed nearly $3 million in deposits. That account’s balance at the end of September 2009 was just $1,325.98. As he once said to his investors, “Bottom line is: I love cash flow. I like lifestyle.” There were stays at the Bellagio in Las Vegas, the Beverly Wilshire, and other high-end hotels. One bill alone, for the Wynn Las Vegas Resort, totaled $9,628.22. The VIP treatment at clubs. A BMW. A $7,000-a-month oceanside condo in Miami. It wasn’t just him: Donna McKelvy was routinely making $20,000 withdrawals. Though it was Wayde who doled out the biggest bucks. In one three-day spree in Las Vegas, he spent nearly $25,000 on three pieces of Cartier jewelry, which, Donna has said, wasn’t for her.

McKelvy and Donna met in the late 1980s at a party in Denver, just after graduating college. The two married not long after and had twin girls. Donna went into the insurance business, while he launched a string of business flops.

By the time of the jewelry purchases in summer 2009, his and Donna’s marriage had disintegrated. McKelvy had moved to Miami full-time. There’s a good chance the jewelry was for McKelvy’s new girlfriend, a woman named Angela. Obviously years younger than McKelvy, the woman had platinum-blond hair, fake breasts, and a backside so pronounced that people close to him speculated it was enhanced with implants. McKelvy’s friends whispered that there was something about Angela that was…no one could seem to quite put their finger on it.

Meanwhile, on investor calls, every offering was better than the last, each a galactic chance at wealth—and possibly the final one. In a summer teleconference, what McKelvy called his “heart-to-heart,” he talked about how a new deal netting 55 to 100 percent annualized return was the “biggest, most generous offer we’ve ever made.… You guys are sitting there with Mantria on the cusp of greatness, in my belief,” he said softly, sounding on the verge of tears. “In my heart of hearts, I believe that. We’re on the cusp of greatness here.”

A few months later, in mid-September 2009, McKelvy told investors that Mantria had secured somewhere between $250 million and “over $1 billion” in financing, and it was the happiest day of his last five years. One caller was—at last—skeptical, and asked, “Is [the biochar technology] generating any revenues at this point?” Wragg skirted the issue, and when McKelvy jumped in, he finally admitted, “Right now our biochar sales are not explosive…but we do have a lot of orders.”

McKelvy implied that he’d heard similar concerns before, and that he was sick of it. “It’s time people get off the fence,” he said. “You know, I preach and preach and preach. I teach people strategies, but it always comes down to action. People say there are the haves and the have-nots in the world. That’s not true. It’s the wills and the will-nots. The people that do. And the people that do nothing.” It would be one of the last investor calls. A few weeks later, an October 7 letter from the SEC notified McKelvy that he and Mantria were under investigation.

“I probably shouldn’t talk to you,” McKelvy told me, “but that’s just who I am.” It was last February when he called, and since I’d left several messages for him and heard nothing, the call was unexpected. He sounded as if he were resigned to being the subject of the SEC lawsuit. He sounded almost as if he understood the reasons for it. And he seemed to shrug it off: “It’s the game I love,” he said. “I could care less about the money. My love is the game.” There’s evidence in McKelvy’s past that he views business as a game, and, to hear it from some of his former clients, he doesn’t play fair.

While Donna built a career in insurance and her husband opened that string of businesses, between 1995 and 2005, they owed the federal government more than $420,000. They were also named in a number of lawsuits. One lawsuit against McKelvy involved Conifer residents Cathy Reynolds and her husband Pat. Beginning in 2000, Cathy says, McKelvy called her numerous times out of the blue, claiming the company holding her mortgage was going out of business; she should stop sending payments. Not to worry, though; he was seeking a solution. McKelvy, as Cathy recalls, was direct but comforting. He played up his family, talking about his wife and daughters. According to Cathy’s 2002 suit filed in Jefferson County District Court, McKelvy told Cathy she “was just a number to the bank, not to call because they didn’t care about [her] and that he could help resolve her situation.”

Cathy says that if her home wasn’t going to be foreclosed on before McKelvy persuaded her to stop making payments, it certainly was after. Through a series of convoluted maneuverings—and what the Reynoldses say was a forged document—the mortgage was transferred numerous times. (At one point, it filtered through Jaguar Group LLC, whose head was himself recently convicted of a $3.4 million Ponzi scheme.) In the end, the Reynoldses and McKelvy agreed to disagree and the case was dismissed. Along the way, the couple filed for bankruptcy to halt their home’s public auction and reclaimed it by signing a mortgage double the amount of their original.

In researching their case, Cathy says, they came across other people who had been stung the same way. The suit may have been the first record of McKelvy being at the center of a muddled transaction that he initiated and from which he likely profited. “If he was covered in gas in front of me,” Pat Reynolds says, “I’d provide the match.”

By the mid-2000s, McKelvy had moved on to form an investment club called Retirement TRACS. It was at one of its meetings that Louisville, Colorado, resident Mary Phillips met McKelvy. Phillips is a self-assured woman with a Ph.D. in American studies. When she picks up a call, she answers, “This is Dr. Mary Phillips.” At the workshops she attended, McKelvy was a man of “simple American humor” and a bit brash. (He once yelled at a seminar, “What’s wrong with you folks? You expect change but you don’t change!”) Nonetheless, he struck her as a guy giving middle-class Coloradans a chance at investments usually reserved for the rich. Phillips and her husband lost a total of $500,000 to McKelvy and Mantria.

It’s tempting, perhaps, to characterize Mantria’s investors as unsophisticated suckers, but research says otherwise. Most are like Phillips: college-educated, higher-income, and more financially literate. With some investment knowledge, people tend to overestimate their ability to smell a raw deal, which researchers believe makes them vulnerable to scams. They also happen to be more prone to emotional pitches. Besides, Phillips points out that her husband went to Tennessee to see the Mantria-owned property, he saw the machine that made biochar, and even received a bag of the stuff. (Real in that it existed, but was nothing more than a facade.) As Phillips says when asked why she believed in sky-high returns, “Wouldn’t we all just like to catch a break, get something really good? It’s the American dream.”

At TRACS investment club meetings Phillips attended, McKelvy tapped into that desire. To play with the big boys, he preached liquidating all traditional funds and buying a universal life insurance policy, which, of course, he would sell. This plan acted as a sort of self-lending system, from which people could borrow at a relatively lower rate and invest in higher-return opportunities. What opportunities, exactly? Well, McKelvy had the scoop on some deals. On his advice, the club would roll $11.4 million into corporate bad debt and real estate in Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and even Granby, Colorado. McKelvy would bring a deal to the club and say the returns were between 12 and 50 percent. Then he’d tilt his head back and crack a sly smile as if to say, Wait till you see what you really get. Running TRACS, McKelvy himself did well enough that Donna could leave her job in insurance. She came to work with him as his secretary. Meanwhile, to the club’s consternation, none of the investments panned out or paid out.

Of all McKelvy’s TRACS-proposed deals, none were as ludicrous as the $250,000 expenditure on a supposedly rare pink diamond. According to what McKelvy told his members, they could double their money over a year by purchasing the gem and flipping it to one of the potential buyers. He whetted the club’s appetite when he mentioned one particularly interested party: Jennifer Lopez. McKelvy told investors that TRACS purchased the diamond, but no members ever saw it, and it never sold. One investor refers to it as the “diamond boondoggle.” Nearly all of the $11 million invested under the auspices of McKelvy’s TRACS was never seen again.

In 2007, after he met Troy Wragg, McKelvy presented an incomparable invitation to his TRACS members: A chance to get in on the ground floor of a growing green company. This wasn’t just about wealth—it was about investing in the future of humanity. Incredibly, some of the club members followed McKelvy’s new advice. However, several other folks had seen enough, and filed complaints with the Colorado Division of Insurance. The SEC was brought in. (The SEC declined to comment on the record for this story.) McKelvy’s explanation comes by way of what he told his investors: “The SEC brought me forward in 2007 and dismissed it.”

A year later on May 30, 2008, the Colorado Division of Insurance notified the Colorado Division of Securities that a new complaint was filed against TRACS. At this point, McKelvy was devoted to raising money for Mantria. It wasn’t until January 30, 2009, that a state securities investigator, Jerry Lowe, asked the insurance division for the emails sent from McKelvy to the initial complainant.

In those emails, investigator Lowe read about green technology with the potential for gigantic returns. Five months after asking for the emails, the investigator attended two seminars. During one, Lowe listened as Wragg raised the prospect of “hundreds of percent rates of return.” That seminar occurred on May 21, 2009, almost a full year after the Division of Securities first received the complaint. The SEC, according to court testimony, wasn’t brought into the Mantria investigation until about five months later in “late September, early October of 2009.”

Miles Gersh, a local securities lawyer, says the SEC is efficient after charges have been filed. But “as far as [the SEC’s] ability to stop wrongdoing before the fact, though, they are a bit like traffic officers: many intersections, relatively few cops.” Regulators at all levels tend to be zealous guardians of their work product, Gersh says, which is a polite way of saying all of the state and federal investigative bodies are territorial and each wants to make the bust. Competency isn’t the problem, he says, it’s “unwarranted, counterproductive secrecy.”

“The primary reason” the SEC is tapped to help, says Colorado securities commissioner Fred Joseph, “is when multiple states are involved.” The Mantria case certainly fit the bill. The company was registered in Delaware, based in Philadelphia, selling projects in Tennessee, and raising funds out of Colorado. Yet it’s reasonable to conclude that if the state securities division had bothered to scratch the surface of Mantria, it would have brought in the SEC sooner.

When the SEC did initiate an investigation in fall 2009, it acted quickly. Within a month and a half, it filed its lawsuit and froze the assets of Mantria, Wragg, McKelvy, Speed of Wealth, Donna, and Wragg’s partner, an Amanda Knorr. For every Mantria investor, it was too late. By that time, investors had poured in more than $54 million.

On November 16, 2009, the news broke of the SEC’s filing against McKelvy and company. The news release said representations by McKelvy and Wragg were “laced with bogus claims.” At that point, as McKelvy himself has said, “I sat down and started reinventing myself at that moment.” Wayde McKelvy soon re-emerged as Clint Brashman, now apparently up to some of the same old business—and with a pornographic twist.

In the wake of the SEC’s filing, numerous websites popped up exhorting Americans to rid themselves of traditional investments, and were registered to a man named Clint Brashman. A search for that name brings up multiple videos offering marketing advice. One was posted on June 5, 2010, by “thebrashman,” and opens with a guy speaking directly into a camera. He’s thinner now and has grown a goatee, but there’s no mistaking it: It’s McKelvy.

“The Brashman” hasn’t restricted his pursuits to marketing and financial sites: He’s tied to a porn site as well. The Brashman’s email is listed as the administrative contact for a pornographic blog, where on the first page viewers see another familiar face, this one framed with platinum-blond hair dropping past fake breasts. It’s Angela. On the website she reveals she is a transsexual. She writes on her blog that her boyfriend “lost all his money” at the beginning of 2010 and “drinks too much.” Nonetheless, he’s done a lot for her, and she loves him still. They’ve been together in Miami for two years.

Initially, McKelvy told me he has nothing to do with that blog or an accompanying site that recruits other transsexual folks to produce pornography. He denied this even though the recruiting site is registered to his old business, Retirement TRACS Seminars. Confronted with these connections, McKelvy then said he’s made no money from his pursuits as Clint Brashman. “Why should I legally make any—that’s going to come out wrong—why should I make any income? What good does it do for me to make any money? The [SEC] is just going to take it.”

Speaking in the slight drawl that fed his image of a good-hearted Coloradan, McKelvy said that he may have done some things wrong. As far as Mantria, he admitted to the definition of a Ponzi scheme while bafflingly denying it was a Ponzi scheme: “I don’t care what the lawyers at SEC tell you; when you invest in mortgage-backed securities, they take money and go loan it to John Doe to buy a house. Doe makes payments and it flows back to me.… What I’m trying to say is that new money is always replacing old money in any investment.”

He rambled during the conversation, one minute saying those who lost money are the true victims; a minute later he lamented his crumbling reputation and compared those upset about losing their savings to homeowners complaining about their subprime mortgages. They could have asked questions, he said, done their own due diligence. “Not to sound like an asshole, I think it’s time Americans start taking some responsibility. I get that from my ex-wife now. Everything bad in her life is my fault.”

A few days after our phone conversation last February, McKelvy signed an agreement with the SEC in which he neither admitted nor denied the SEC’s allegations. However, according to the Order of Permanent Injunction, McKelvy “will be precluded from arguing that he did not violate the federal securities laws as alleged,” and furthermore, will not “take any action or to make or permit to be made any public statement denying, directly or indirectly, any allegation in the Complaint or creating the impression that the Complaint is without factual basis.”

According to the SEC resolution, fines still could, and likely would, be levied against him on behalf of Mantria’s investors. And this SEC settlement agreement does not preclude the possibility of related civil actions, or, say, criminal charges that might come from the FBI. (Wragg, Knorr, and McKelvy’s ex-wife, Donna, signed similar orders.)

To date, no criminal charges have been filed against anyone involved with Mantria, but a couple of investors have been contacted by the FBI. Agents want to know what claims investors heard, what they were promised, and how much they lost. It’s unclear whether agents know about a guy named Clint Brashman.

“All of us have our own life lies that we tell ourselves,” Mantria investor Dr. Mary Phillips said about McKelvy. “Who we are, what we stand for. For Wayde, he wanted to be the ringmaster. He wanted to sway public opinion. Maybe he was lying to himself about what he was doing.”

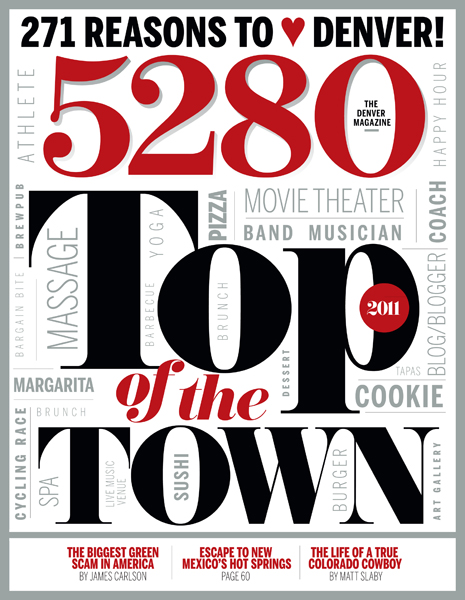

This is James Carlson’s first piece for 5280. He is a Denver-based freelance writer. Email him at letters@5280.com.