The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Read an update on CBD legislation here.

My nephew, David Barry, is only eight years old, but I already know how he will die. It will start suddenly. His arms and legs will jerk outward; in lighter moments, his parents call this pose his “Superman.” His mother—my older sister, Tami—will look at her black and silver Timex Ironman watch. She’s never without it. Tami times every seizure because she never knows if it will last a few seconds or a few minutes. It’s the long ones she worries about.

After several seconds, David’s body will curl into a C, his arms and legs will flail violently, and his mouth will be pulled back tightly at the corners. His eyes will twitch and roll back into his head. His muscles’ vigorous spasms will suck oxygen from his system. His breathing will become irregular. The full-body convulsions, known in the medical community as tonic–clonic seizures, can induce vomiting, so Tami will lay him on his right side so he doesn’t aspirate. She will be calm. These massive seizures—or clusters of them—happen at least every other day.

At three minutes, Tami will prep the Midazolam, a sedative typically given before general anesthesia in surgery, which she can give David via nasal spray. She prefers to use it instead of Diastat, which has to be administered rectally and costs 20 times as much as Midazolam. These medications come with serious psychoactive side effects—they compromise cognition, perception, even consciousness—but as Tami and her husband, Dwight, darkly joke, when you’re trying to keep your kid alive, you’re not especially concerned with whether or not he knows his own name.

At five minutes, she will give David 0.7 milliliters of Midazolam. She’ll still be calm. As David has grown older, using these rescue meds has become a near weekly occurrence. It will be quiet. David won’t cry. He can’t: His jerking, contorted body is too busy fighting itself.

At six minutes, when the Midazolam hasn’t taken effect, David’s face will pale. The area around his mouth will turn blue. Tami will blow gently on his face, which sometimes stimulates breathing. If it doesn’t, she will give him rescue breaths, about four a minute depending on his breathing pattern. When her watch says it’s been nine minutes, she will administer another dose of Midazolam, and her own heart rate will begin to climb. She can only give David one more dose. The powerful sedatives stop seizures by slowing the central nervous system. That means they also affect involuntary activities like breathing, which is why any more than three doses of Midazolam or two doses of Diastat in 24 hours require a trip to the emergency room, where doctors can give David more and stronger sedatives with proper respiratory support.

Between rescue breaths, Tami will scan the room for her cell phone. With David still seizing and breathing irregularly at 12 minutes, she will prep her last dose of Midazolam. A minute later, she will give it to David, grab her phone, and dial 911. The ambulance usually takes 10 minutes to get to their home in Edmonds, a northern Seattle suburb. When the ambulance arrives, David will still be seizing, struggling to breathe, his fragile brain battered by a storm of electrical pulses, his own body suffocating him. His doctors have warned Tami about this day: the day the Diastat and Midazolam will lose their effectiveness, the day the drugs will fail to stop the seizure, the day there will be nothing left in the arsenal.

The doctors and Tami and Dwight have known this day was coming for years. Small shudders gripped David’s body just hours after he entered the world on September 4, 2005—the first signs of catastrophic epilepsy wrought by a suspected mitochondrial disorder. These intractable seizures have stolen any chance David had at normal. He cannot see. He cannot hear. He can’t hold his own head up. Today, at age eight, he has the developmental abilities of a three-month-old. He eats through a tube surgically implanted in his stomach and vomits so often he weighs just 40 pounds. Every day, between 10 and 20 seizures ravage his shrunken body, sometimes more. Someday these seizures will also take his life. In the face of the inevitable, Tami and Dwight desperately seek ways to ease their son’s suffering—to make the time David has left as painless as possible—and to put off the end they know is coming, if only for one more day.

Thirty-five miles northwest of Colorado Springs, 13,852-foot Crystal Peak rises unremarkably near more storied Tenmile Range summits such as Quandary Peak and Peak 10. But this stony mountain held special meaning to the area’s first residents: The Ute Indians believed Crystal Peak to be a spiritual place. It was here, according to author and historian Celinda Reynolds Kaelin, members of the tribe’s ceremonial circle gathered sacred stones and carried them to Pikes Peak, where one person delivered them to the summit during a four-day vision quest.

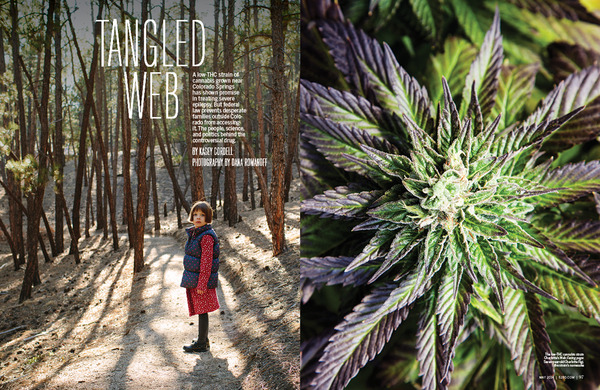

Today, in the shadow of Crystal Peak, a new kind of healing ground has emerged: the Stanley brothers’ cannabis grow facility. Amid a rolling high-country landscape, Joel, Jesse, Jon, Jordan, and Jared Stanley cultivate roughly one acre of marijuana inside two hand-built greenhouses, making the brothers owners of one of the largest medical marijuana grow operations in the state.

The clean-cut Stanley brothers are unlikely pot-growing pioneers. A large, devout Christian family (seven brothers, four sisters), the Stanleys moved from Oklahoma to Colorado in 1994. Their father left in 1997, and their grandmother moved in to help hold the family together. As an only child, their mother, Kristi, wasn’t sure how to raise 11 children, but she let scripture guide her, regularly repeating this verse from Philippians: “Do nothing from selfishness or empty conceit, but with humility of mind regard one another as more important than yourselves.” That mantra binds the brothers all these years later.

In 2008, the eldest Stanley brother, Josh, established Budding Health, one of the first medical marijuana dispensaries in Denver. He called his brother, Joel, who had been working in the Texas oil fields as a fluids engineer, to gauge his interest in the industry. “At first I just laughed at him,” Joel says. “I thought medical marijuana was a joke.” Upon meeting a few of Josh’s patients weeks later, though, Joel reconsidered. Many were suffering from cancer, wasting away because of nausea and lack of appetite. “No one thinks of the munchies as being medicinal, but if you’re going to die because you can’t eat, then they’re extremely medicinal,” Joel says. “I changed my tune.”

A few months later, in the summer of 2009, Joel, Jesse, Jon, Jordan, and Jared pooled their money to buy their first full grow setup. They started with six lights in a Fort Collins basement. As caregivers under Colorado’s medical marijuana laws at the time, the Stanleys were allowed to grow six plants per patient. The brothers wholesaled their product to Denver-

area dispensaries and provided a concentrated THC oil to their patients for free. They poured profits back into the crop and took on more patients.

One of the Stanleys’ first clients was their cousin Ron Fortner. A stage IV pancreatic cancer patient, Fortner died just six months after the Stanleys started cultivating marijuana, but in that short time he helped advance the brothers’ interest in a promising field of cannabis research: cannabidiol. Most people are familiar with the plant’s major psychoactive compound—tetrahydrocannabinol (THC); fewer people know about cannabidiol (CBD), one of the other 400-plus compounds in cannabis. In searching for ways to help their ailing cousin, the Stanleys discovered scientific literature suggesting CBD had antioxidant and neuroprotectant properties and the ability to help reduce inflammation, ease pain, and even, in some lab studies, shrink tumors. Most cannabis plants, though, have fairly low levels of CBD; over the years, they’ve been bred to have more THC. The Stanleys figured the reverse—high CBD, low THC—must also be possible, so they began to tinker with crossbreeding.

Although their grandmother had been a florist and their grandfather a farmer, none of the brothers had a formal background in horticulture or botany when they started cultivating cannabis. Not long into their growing endeavor, however, the Stanleys met an older gentleman who’d spent his career as the head of several commercial tomato greenhouses. “We’d buy him coffee,” Joel says, “and he’d tell us everything he knew.”

By 2011, the Stanleys had bred a cannabis plant with more than 15 percent CBD and less than half a percent THC content. But for what purpose, they weren’t sure. Most medical marijuana cardholders didn’t want it; it couldn’t get you high, which was why the brothers nicknamed the strain “Hippies’ Disappointment” (among other names, such as “The Future”). By then, after a few years spent in basements, barns, and warehouses, the brothers had established their Teller County grow site. Inside the greenhouse, they kept a few Hippies’ Disappointment plants to treat cancer patients. The Stanleys knew the strain had potential for something more, but what? The answer came that winter, when they met a Colorado Springs mom named Paige Figi.

In early October 2006, my phone buzzes on my office desk. It’s my dad. I silence the call. Still finishing up editing projects in preparation for a work trip to Vancouver, British Columbia, the next day, I figure he can wait. I set the phone down as the electronic chime for a voicemail sounds. I hesitate. Might as well listen to his message, I think.

Hey Kasers, I’ve got some news about David. It’s not good…call me back when you get a chance.

I draw a shaky breath. We’ve been waiting for some kind of answer for almost a year, since David was diagnosed with infantile spasms at two months old. I walk out into the sunshine cooking the office’s rooftop deck and dial my dad.

“They got the results of David’s MRI today,” he says. “It revealed he’s missing part of his brain—most of the corpus callosum, the part that helps the right hemisphere talk to the left. They don’t know why—it could be a symptom of his underlying condition—but they don’t expect him to last more than a couple of years.” He sighs, almost inaudibly.

I stop pacing and pause in front of a large potted plant desiccated by the Indian summer and fixate on its shriveled and bowed branches. Beneath the sun, I feel the hope we’d clung to since David’s initial diagnosis evaporate in the flatness of my father’s voice and his slow, unsteady exhale.

At about the same time, more than 1,300 miles away in Colorado Springs, Paige and Matt Figi’s nightmare was also beginning, although they didn’t yet know it. On October 18, 2006, Paige gave birth to twin girls, Charlotte and Chase. For three months, the Figis reveled in the joy of their growing family (they also had a two-year-old son, Maxwell). Then Charlotte—“Charlie,” as her family calls her—had her first seizure. And then she had more and more and more—at least one a week. By 18 months, she had started to regress: She stopped talking, walking, crawling. At two, she was having up to 20 seizures a day. Finally, when she was two and a half, after a $7,000 genetic test, Charlotte was diagnosed with Dravet syndrome, a rare disorder that accounts for a portion of the more than 100,000 American children who suffer from severe epilepsy.

Charlotte’s doctors set out to find a drug that would help control her seizures. First they tried Keppra, an antiepileptic drug (AED) with side effects that can include drowsiness, weakness, throat irritation, memory loss, high blood pressure, and severe mood swings. (In fits of “Keppra rage”—sudden, unreasonable outbursts of anger and aggressive behavior—children sometimes attack their parents or harm themselves.) Next came Depakote, which can be so damaging to the liver that doctors typically run blood tests every three to six months to monitor the organ’s health. By the time they tried Trileptal, Paige was losing hope. The doctors had told her that after a child failed to respond to three antiepileptic drugs, her chance of responding to any others was less than one percent. The Trileptal didn’t work. Neither did acupuncture, herbal supplements, craniofacial therapy, or any of the other “alternative” remedies Paige and Matt, an Army Special Forces staff sergeant, sought to save their daughter.

By the time she was five, Charlotte had tried more than a dozen antiepileptic treatments. They all failed. The next option was an antiseizure medication for dogs. The Figis’ cherubic daughter was so frequently plagued by seizures that she couldn’t sleep. She couldn’t eat or drink. Like my nephew, David, she had a feeding tube, and at five, Charlotte was functioning at the same level as a one-month-old. Her doctors said there was nothing more they could do; they weaned her off her last drug. Her parents signed a do-not-resuscitate order. “She had pneumonia and was on oxygen,” Paige says. “It was looking very, very bad.”

In 2011, on the eve of another deployment to Afghanistan, Matt said what he feared might be a final goodbye to his five-year-old daughter. But even when he was nearly 8,000 miles away, Matt continued searching for a reason to hope. Before he left, the Figis had heard about a father in California using a strain of marijuana to treat his son. While Matt was overseas, he found a moving YouTube video of the father and son. “Matt called me on the satellite phone,” Paige remembers. “Charlotte’s seizing, and he’s listening to her scream, and he’s pushing me to understand: ‘We live in a legal state. You’ve got to try this.’?”

At first, Paige said no. Too many times she’d been gored by the horns of disappointment. The pain was just too much. Not again, she thought, not again. But then she’d look at her seizing daughter and wonder, What if I don’t try and she dies? What if?

It took more than a month and no small amount of convincing to get the two doctors’ signatures required to attain a medical marijuana card for a five-year-old. Eventually two physicians—Colorado Springs’ Dr. Margaret Gedde, who holds an M.D. and a doctorate in biophysical chemistry from Stanford, and Denver’s Dr. Alan Shackelford, one of the foremost medical marijuana experts in the world—signed for Charlotte, making her the youngest red-card holder in Colorado history.

Paige spent another month calling dispensaries and growers, often holding Charlotte’s seizing body in her arms as she inquired about high-CBD strains. A mutual acquaintance of Paige and Joel Stanley who knew about Hippies’ Disappointment put the two in touch. Within hours, Joel was standing on the Figis’ doorstep. He spent more than an hour with Paige and Charlotte and saw

the first two seizures of his life. A father of three who’d lost one of his own children, a girl, just a few hours after her birth to Potter’s syndrome, Joel needed no further persuading. He left and gathered the brothers. A few weeks later, Paige gave Charlotte her first dose of the high-CBD extract mixed in olive oil—and waited.

Seven days passed before Charlotte had another seizure. Paige couldn’t believe it was the oil. Over the following week, the seizures slowly returned. Paige upped the dose; the seizures eased. “I hate to say I used my child as a guinea pig,” she says. “But I did. We didn’t have anything else. And the fastest way to find out what’s working is to see what fails.”

Charlotte has taken the high-CBD oil ever since. Eight months in, she was down from 1,200 seizures a month to two, a 99 percent reduction. She started talking and walking—even dancing—again. The Stanleys renamed the plant in honor of their first patient: Charlotte’s Web. They started a nonprofit, the Realm of Caring, with Paige Figi and Heather Jackson, the mother of another Colorado Springs child using Charlotte’s Web, to help distribute the extract to families in need. Word spread through a private Facebook page for parents of kids with seizure disorders. CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta profiled the Stanleys and Charlotte in an August 2013 special titled “Weed.” By then several other families had started using the oil and were seeing their own kinds of success: Heather Jackson’s son, Zaki, went from hundreds of seizures a day to zero, and today, the 11-year-old has been seizure-free since October 4, 2012.

The Stanleys watched the waiting list for Charlotte’s Web, which had been zero, jump to several hundred in a few weeks. “Where can I get this in my state?” parents from all over the country asked; my sister and Dwight were among them. They were dismayed by the answer: nowhere. Although Charlotte’s Web is legal under Colorado law, it is still a federally illegal Schedule I drug; sending or transporting just a small amount across state lines—even to other states with legalized medical marijuana—qualifies as a federal drug trafficking offense that comes with a potential five-year prison sentence and a $250,000 fine. For children outside Colorado—for my nephew, David—Charlotte’s Web was out of reach.

You won’t find cannabis in today’s U.S. Pharmacopeia, an annual guide to medicines and supplements used in the United States that’s been put together by a collection of American medical societies since 1821. But if you open the illustrated 1851 edition and turn to page 50, it’s there. Right below “Euphorbia Ipecacuanha,” the entry for “Extractum Cannabis” reads: “an alcoholic extract of the dried tops of Cannabis sativa—variety Indica.” Following physician William O’Shaughnessy’s 1839 discovery that cannabis tinctures relieved muscle spasms in tetanus patients and stopped vomiting in cholera sufferers, cannabis made its debut in the Pharmacopeia, where it remained for 92 years.

In 1970, President Richard Nixon initiated his war on drugs with the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), which sought to combine all existing drug laws into a single statute. In it, Congress classified substances on a schedule from I to V, based on the drugs’ accepted medical uses as well as their potential for abuse. Schedule I contained the most dangerous substances, those with “no currently accepted medical use” and “a high potential for abuse.” Roger O. Egeberg, then assistant secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs, placed marijuana on Schedule I pending the findings of a report from the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse, headed by the Republican governor of Pennsylvania, Raymond Shafer.

Despite warnings from Nixon to “keep your commission in line,” in 1972, Shafer delivered a report, “Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding,” to Congress, which called for the reclassification of the drug and recommended a federal policy that decriminalized possession of small amounts. “Looking only at the effects on the individual, there is little proven danger of physical or psychological harm from the experimental or intermittent use of the natural preparations of cannabis,” the report said. Ultimately, the commission found “that the existing status of marijuana under the Single Convention [the International Drug Schedule] is not appropriate.”

Nixon and his cabinet ignored the recommendation. Cannabis has remained a Schedule I drug ever since, despite the fact that a majority of Americans (55 percent) favor its legalization and despite recent urgings—from the American College of Physicians, and, just this spring, the American Epilepsy Society, among others—that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) look at reclassifying marijuana to allow for more research into its potential medical uses.

Rescheduling a drug is no easy thing. Congress can reschedule it—after all, it created the CSA—although lawmakers have rejected every such bill so far. The process also can be initiated by the attorney general, the secretary of Health and Human Services, or by a petition from any “interested party,” which includes everyone from drug manufacturers and medical societies to state government agencies and private citizens. Once the rescheduling process has been triggered, the DEA relies on scientific and medical evaluations from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—as well as its own research—to help inform its decision. (However, section 811 of the Controlled Substances Act states: “If the Secretary [of HHS] recommends that a drug or other substance not be controlled, the Attorney General shall not control the drug or other substance.”)

The process can take years, decades even. The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) and others filed a petition in 1972. In 1988, after 16 years in legal and bureaucratic purgatory, a DEA administrative law judge issued a ruling, which found that cannabis should be a Schedule II drug. The DEA rejected the ruling. The most recent petition for rescheduling, a 2002 suit brought in part by Americans for Safe Access, was denied by the DEA in June 2011. An appeal was dismissed in 2013. In its denial, the DEA cited the drug’s high abuse potential and the HHS determination that cannabis has “no currently accepted medical use.” Interestingly, eight years earlier, the Department of Health and Human Services patented cannabidiols as neuroprotectants and antioxidants, very clearly stating their potential use in “the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and HIV dementia.” The National Cancer Institute, part of the HHS itself, also notes that, “Despite its designation as having no medicinal use, cannabis was distributed to patients by the U.S. government on a case-by-case basis under the Compassionate Use Investigational New Drug program established in 1978.” And in 1985, the FDA approved Marinol—synthesized THC—to treat nausea and improve appetite in cancer and HIV patients. Marinol remains legal today.

Even with the federal government’s contradictory policies and pronouncements about cannabis, 20 states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical marijuana. Colorado and Washington legalized the plant altogether, and one state—Oregon—shifted cannabis down on its state schedule. As of this writing, 13 other states were considering legislation to legalize medical marijuana. The Stanleys, Paige Figi, and Heather Jackson have visited many of them. “My child’s name is on this,” Figi says. “She can’t leave the state, so I go fight in other states. I testify at hearings; I meet with other families. I’ve come out with this information, and it would be irresponsible to say there’s this thing that’s working, but you can’t have it. So now we have a responsibility to create access for other people.”

If the advocacy is effective in all of those states, the demand for Charlotte’s Web likely will increase. Already, the Realm of Caring’s waiting list has ticked past 5,000. And that number doesn’t account for the more than 100 families who have moved to Colorado from 43 different states hoping to find their children’s salvation in the foothills of the Front Range.

Tucked on the edge of a golf community on an arid plateau 19 miles east of Colorado Springs, Paula and Jordan Lyles’ modest home overlooks the water hazard on hole 17. “It’s not the beach,” says Paula, who left her five-bedroom house with a 40-foot in-ground pool on the shores of Lake Erie last fall, “but at least it’s water. We have to have water.”

A lifelong resident of Ohio, Paula left her husband, her 25-year-old daughter, and her entire extended family in October to bring her 19-year-old daughter, Jordan, to Colorado. Like Charlotte Figi, Jordan suffers from Dravet syndrome. Like Charlotte, Jordan had reached the end of what traditional medicine could offer. Unlike Charlotte, she didn’t live in a state where medical marijuana was legal. A devout Christian, Paula agonized over the decision to leave her family, her church, and her community behind (and break federal law by giving her daughter cannabis), until last fall, when Jordan began having near-constant nonconvulsive seizures—a dangerous, often fatal situation. Paula got a moving truck, packed Jordan and their eight-year-old cockapoo, Tulip, into her Town & Country minivan, and drove toward the mountains.

“Three days of driving with a cockapoo, all the way through Kansas, Kansas, and more Kansas,” Paula remembers, chuckling. “I know why Dorothy’s house got hit in the Wizard of Oz: Because there’s nothing else in Kansas!”

Paula’s humor and optimism have helped keep this tiny woman afloat through almost two decades of devastation and disappointment, and upon arriving in Colorado, where she knew no one, it also immediately won her friends among the families already using Charlotte’s Web. The Realm of Caring may be the name of the nonprofit, but it could just as easily describe the community of more than 100 families using the extract, most of them in the Colorado Springs area. As more families arrived from across the country—and the world—the Figis, Jacksons, and dozens of others formed a tight-knit collective to help the new arrivals adjust to life in Colorado. When a moving truck pulls up, they arrive with casseroles, dollies, and extra manpower. Whereas the official Realm walks parents through the medical marijuana card application process, finding doctors, and dosages, the unofficial “realm” helps them find school districts, supermarkets, dog parks, auto mechanics, and the nearest Target. They house visiting families who are considering a move. The Figis host an almost weekly bonfire, there’s a monthly support group, and a small runners group recently formed. And there’s a ready pool of experienced baby-sitters for doctor’s appointments, trips to Denver, or even date nights.

For some arrivals, the Colorado collective provides more support than they ever got in their home states. “When you’re dealing with a family member who is so severe, you end up a hostage at home. It’s very isolating,” says Heather Jackson. “So for another family to come over and hang out—it’s amazing.”

Yet moving to Colorado is not without challenges. For some families, the struggle is financial. Many maintain two households, often on a single salary. Even with her husband’s six-figure income supporting the family and help from her father, Paula’s using her old deck furniture as an ingeniously designed dining room set. And there’s the cost of the medicine itself. Although the Realm of Caring provides Charlotte’s Web at about five cents per milligram (or less for families who can’t afford it), a month’s worth of medicine still works out to roughly $300, based on the average dosage. That’s cheaper than what most families pay for traditional AEDs (my sister and her husband pay about $775 a month for David’s meds, after insurance), but they’re able to recoup some of that money in tax deductions. Families can’t do that with Charlotte’s Web; the IRS doesn’t consider cannabis a legitimate medical expense.

For the families who find relief through the Charlotte’s Web oil, though, the financial, emotional, and familial sacrifice is worth it. Jordan is still early in her treatment and on a fairly low dose, but she’s already seen a 75 percent reduction in seizures. She still has some—she had a 15-hour nonconvulsive seizure in January and two scary tonic–clonics—but she isn’t trapped inside her brain for five, seven, 10 days at a time, as she was last summer in Ohio. She recently made it through a full moon without having a seizure, a first. On the day I visit, her pretty blue eyes follow Elmo around the television; she laughs with him and feeds herself spaghetti. “She’s sick today,” Paula says as Jordan drifts in and out of sleep. “This isn’t one of her good days.” But it is another day—something many kids with Dravet syndrome don’t get. Those who live into adulthood frequently do so with great cognitive and physical deficits; few can live independently, and some never regain the mental abilities and motor skills lost to constant seizing in childhood. Their parents often must hire help or remain caregivers until they can no longer care even for themselves. “The seizures are really what need to be controlled,” Gedde says. “They cause brain damage. If you can stop the seizures, they can start to develop again.” It’s too early to say that the overall prognosis for Dravet patients is different because of Charlotte’s Web, Gedde adds. But for some, for the Charlotte Figis of the world, she says: “For those children, we can say their outlook is different. Their lives are different.”

Charlotte’s Web doesn’t work for every child. The second Colorado patient to try it, a six-year-old boy with Dravet syndrome, eventually stopped because, despite some improvement in seizure control, it didn’t stop the large clusters as effectively as the antiepileptic drugs he was on. “It was so sad to see this mom, stepping so far outside of her box, hoping so badly that something was going to work…and then it didn’t,” Joel Stanley says. “It was a horrible thing to watch.”

The drug doesn’t appear to have a greater effect for one seizure group over another. A 2013 report in Epilepsy & Behavior based in large part on Charlotte’s Web patients revealed 16 of the 19 study subjects saw a reduction in seizures after taking high-CBD oil. Of the three who didn’t, two suffered from Dravet and the other from Doose syndrome. And a report Gedde and Denver Health neurologist and epileptologist Dr. Edward Maa presented at the annual American Epilepsy Society conference this past December noted that seizure reduction in patients for whom the high-CBD oil worked varied vastly, from as much as 99 percent down to 25 percent. Those are realities the Realm of Caring’s executive director, Heather Jackson, makes clear in every conversation with families considering Charlotte’s Web. “This isn’t everyone’s magic bullet,” she says.

Of course, aspirin doesn’t work for everyone’s headaches either. Claritin doesn’t alleviate everyone’s allergy symptoms. Herceptin doesn’t stem tumor growth in all breast cancer patients. The difference, many physicians have argued, is that we at least understand how those medications interact with the body, while not as much is known about how cannabis operates. (It’s worth noting that researchers don’t fully know how Depakote works in the human body, either, and it’s still regularly prescribed to stop seizures.)

The mystery is partly because the system cannabis seems to primarily affect—the endocannabinoid system—has, until recently, been a poorly studied part of the body. “I was shocked as a person who went to traditional medical school at LSU, through traditional residency at the University of Colorado, that we didn’t learn this stuff,” Maa says. “When my patients started telling me they were using cannabis, I figured I needed to go read more about it, and I discovered this entire system. I thought, ‘Why isn’t anybody studying this?’?”

They are. PubMed, a searchable database of biomedical literature, returns nearly 3,000 results for “endocannabinoid system.” What the research has shown so far is that cannabinoids, which the body produces on its own, can have a quieting effect on the excessive electrical activity during a seizure. “The brain communicates using electricity that is exquisitely patterned and needs to happen in precise ways—like in an orchestra, each instrument plays a specific role,” says Dr. Amy Brooks-Kayal, vice president of the American Epilepsy Society and professor of pediatrics and neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “A seizure is like the warm-up, when the musicians are all playing loud and hard at the same time.” When a nerve cell in the brain gets overexcited—as with seizures—cannabinoids, like many other chemicals, can essentially play conductor and help settle the excessive activity.

How they do that is a question researchers such as Shackelford and Dr. Raphael Mechoulam—another of the world’s top medical marijuana experts—are working to answer. Mechoulam has conducted marijuana research at Israel’s Hebrew University in Jerusalem for years. He often consults with Shackelford, who maintains a private medical practice on South Broadway and a rehab facility in Aurora.

But conducting research in the United States is extraordinarily difficult because of cannabis’ status as a Schedule I drug. American researchers can only get marijuana from one place: the University of Mississippi, which provides it to them only after a complicated approval process. The lengthy process includes internal review by the university or institution where the research will take place, as well as a separate review by the appropriate National Institutes of Health branch or the HHS. Additionally, the researcher must get DEA approval to store the cannabis, and, for research on humans, have an approved Investigational New Drug application on file with the FDA. Once a researcher’s application has been approved, the National Institute of Drug Abuse acts as the liaison with the University of Mississippi. Last year, Ole Miss received zero requests for cannabis for epilepsy research, according to Dr. Mahmoud A. ElSohly, director of the school’s marijuana program. Despite that, Ole Miss is currently growing a high-CBD strain in anticipation of future research requests.

The limitations that stem from having a single marijuana source for researchers are absurd, says UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs professor Mark A. R. Kleiman, one of the country’s foremost drug policy experts. He points out that it’s easier to get heroin from one of the country’s licensed manufacturers. “The right thing to do is to get rid of the stupid rule that says in order to do research with marijuana, you need to get it from the University of Mississippi through the federal government. Get rid of that bullshit, and then we can do work.”

For now, then, why and how Charlotte’s Web works for some and not others remains a mystery, which concerns many physicians working with severely epileptic children. “While there are a number of anecdotal reports of positive outcomes from a particular strain of marijuana used for treating patients with epilepsy, robust scientific evidence for the use of marijuana is lacking,” wrote Elson So, president of the American Epilepsy Society in a January Miami Herald op-ed that echoes the AES’s official position on using cannabis to control seizures. “In addition, little is known about the long-term effects of using marijuana in infants and children on memory, learning, and behavior.”

On the other hand, Maa says, we do know that having 50 convulsions a day is very bad for your brain. Moreover, for many of these children—my nephew included—there simply is no long term. Genetics have forced them into playing a kind of Russian roulette with their bodies; every seizure represents another pull of the trigger. Parents like Tami and Dwight are simply looking for a way to slow down the cruel, inescapable game.

Just a few miles from where the pavement of one Teller County country road gives way to a rutted dirt lane, the Stanley brothers’ grow facility sits on 52 aspen-and-pine dotted acres. “This place is special to me,” says 27-year-old Jared Stanley, one of the site’s directors of production. (His brother Jordan is the other.) A construction management grad from Colorado State University, Jared lived here for a year and a half while he built the two greenhouses—one 10,000 square feet, the other 6,000—that currently hold about six months’ worth of medication for 120 children. Today, he oversees seven fresh-faced twenty- and thirtysomethings at the facility, where Charlotte’s Web makes up 80 percent of the crop. The other 20 percent are high-THC strains sold at the brothers’ Colorado Springs dispensary, the Indispensary, which helps underwrite the Stanleys’ operation.

Jared and his team harvest the crop twice a year, then bag it and store it in a modest house up the hill that serves as headquarters. A sweet, grassy scent that’s quite different from the skunky aroma of high-THC weed you frequently smell walking around Denver perfumes the back room. Large Home Depot–style plastic bins locked in the house hold the plant materials until an order comes in for the oil. Then Jared, or one of the site’s shipping managers, sends the trimmed Charlotte’s Web material to the Stanley brothers’ Denver lab, where Jesse creates an extract using an alcohol solvent, a strainer, and a rotary evaporator and mixes it with olive or coconut oil.

Every patient has a specific medication, so Jesse spends 70 hours a week ensuring each formula is just right. He tests them three times using a high-performance liquid chromatograph—a fancy piece of lab equipment that separates chemical components—to affirm they have the appropriate ratio of CBD to THC (Charlotte’s Web is typically in the neighborhood of 30:1) and don’t contain any residual solvents, molds, mites, or pesticides (the Stanleys grow their cannabis organically). Jesse checks his work by sending another sample to Denver’s CannLabs.

The brothers are adamant about maintaining the quality and consistency of their extracts and express the same worry physicians do about knowing what’s in the oil. Concern over quality is one of the reasons the Stanleys haven’t released the strain to many other growers. (While other high-CBD strains exist, none seem to match the high ratio of Charlotte’s Web.) They have licensed Charlotte’s Web to growers in California, Nevada, New York, Illinois, and Canada and are in discussions with others in Oregon, Washington state, and Florida. But they’re picky. “Charlotte’s Web doesn’t need to be associated with a story about a blown-up kitchen or someone getting sick from residual solvents, molds, or pesticides,” Joel says. “These are very sick, very sensitive small children, and they deserve to get it from a source that’s safe and is not going to gouge them.” Last year, the Stanleys hired an in-house chemist—Bryson Rast, who previously worked for Pfizer—to help in the lab. Even with his assistance, Jesse says, they can barely keep up.

And they’re about to get busier. When Colorado legalized recreational marijuana, it also created a provision for approved growers to cultivate hemp, something that’s against federal law. (The United States prohibited growing hemp in the late 1950s, although the 2013 U.S. Farm Bill included an amendment allowing for the establishment of grows at several research institutions.) Hemp, also called industrial hemp, is essentially a strain of cannabis with a very low THC level, less than one percent. Charlotte’s Web regularly tests at less than 0.3 percent THC. So this spring, the Stanleys planted their first outdoor grow: 30 acres of Charlotte’s Web hemp. “We expect to be able to eliminate our current wait list in Colorado through that hemp this fall,” Joel says.

The brothers also are working with the government in Uruguay—where marijuana is legal and land is cheap—to establish a substantial hemp grow, much larger than the one in Colorado. The new endeavor, Stanley Brothers Social Enterprises, will give them the ability to provide Charlotte’s Web to patients outside Colorado by importing the extract as a hemp oil product, just like you might find on the shelves at Whole Foods Market. The United States might have outlawed domestic production of hemp, but it’s still legal to import hemp products such as Nutiva’s Cold-Pressed Hemp Oil and Nature’s Path Organic Hemp Plus Granola. In fact, the United States is one of the largest importers in the developed world: In 2011 alone, we brought in at least $11.5 million in hemp products from Germany, Canada, France, Romania, Hungary, the U.K., and other European countries. By scaling up their business, the Stanley brothers hope they will be able to make Charlotte’s Web more affordable (and that they’ll have a sustainable business). This “social enterprise” model requires shareholders who accept that they might never see their dividends grow as dramatically as their karma. The brothers are OK with that. “When I die, I would like to know that I changed the world and I wasn’t changed by it,” Jesse says. “I can say that now. Because of Charlotte, I’ve been a part of that. Charlotte Figi, Zaki Jackson—these kids are the ones beating down the walls that hippies have tried to beat down for the last 30 years.”

Across the Atlantic, in an undisclosed location south of London, another sizeable cannabis crop grows, courtesy of GW Pharmaceuticals, a British company that’s been rapping on the U.S. FDA’s door for years. Some of the plants are used for Sativex, a 50:50 CBD-to-THC ratio medication approved in 25 countries to treat spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis; it’s in the final stages of clinical testing in the United States to treat cancer pain. Other plants are being used to produce a purified CBD syrup, called Epidiolex, designed to treat intractable pediatric epilepsy. In December, the FDA gave researchers the nod to initiate Investigational New Drug studies (INDs) here for Epidiolex. Twenty-five pediatric patients each at five sites around the country (New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Boston) will be given Epidiolex in concert with their other antiepileptic drugs to measure its effectiveness and how it interacts with other medications.

The major difference between Epidiolex and Charlotte’s Web is that Epidiolex is a purified form of CBD. GW removes almost all of the plant’s other compounds, including THC, when it creates the extract in the lab. While THC has been shown to be a proconvulsant in some studies, others have suggested that a small amount can increase the efficacy of CBD’s antiseizure properties; it’s called the “entourage effect.” The big upside to Epidiolex is that parents know exactly what they’re giving their kids, eliminating concerns over the uncertainty of ingredients and dosage inconsistency. “If you have a child who is extremely sensitive to the medications that they’re taking, giving them an untested, uncharacterized artisanal preparation is a significant concern, and that is being clearly communicated to us by the pediatric epilepsy physician community,” says Steve Schultz, GW’s vice president of investor relations based in the United States. “They need a medicine that’s characterized for safety, efficacy, and how it interacts with other drugs. And that means FDA review and approval. We’re going to get there as quickly as we can.”

“As quickly as we can” may still be two years or more. So, these are the options parents like my sister and Dwight face: Wait and hope that Epidiolex proves to be an effective anticonvulsant and that your child stays alive long enough for it to become a readily available, FDA-approved medication; take your chances with a high-CBD tincture; or do nothing at all. Schultz says he understands the difficult position this puts families in. “As a parent, you do what you have to do for your child, but we believe fundamentally at GW that the proper approach is through FDA-approved pharmaceutical medicine,” he says.

For Tami and Dwight, the choice was clear. David isn’t expected to live much past puberty. He doesn’t have time to wait for the FDA’s thorough, yet plodding, process. But Charlotte’s Web isn’t procurable in Washington, which is why a few weeks into the writing of this story, Tami and Dwight started David on a homemade high-CBD tincture using a different strain—one readily available in Washington—with the help of a family who has been using it for a year. The strain they’re using, Sour Tsunami, has a ratio of about 20:1, versus the 30:1 ratio found in Charlotte’s Web. Tami and Dwight have learned how to extract the CBD and combine it with olive oil (a difficult process that takes four days), how much to give David, and where to send a sample for lab testing. On February 25, 2014, they gave him his first dose and—for the first time in eight years—allowed themselves to hope.

Tami and Dwight aren’t looking for a miracle. The oil won’t change David’s prognosis: Eight years of near-constant seizing have damaged his brain too much; he still won’t see the dawn of the next decade. But it could drastically improve the remaining time he has with his family. His neurologist has said that if they can control the seizures, then brain development can occur, and we could see some improvement in his cognitive and physical abilities. More important, the extract could eliminate some of David’s pain—and the agony his parents experience every time they watch their youngest child fight his way through another round of seizures. And at the very least, it could diminish the number of seizures David has, essentially reducing the number of bullets in the gun.

Could. After a five-week trial, the oil appears to have made little impact. David’s seizures were down only slightly, though he did go one day with no seizures at all (something that hasn’t happened in years). While encouraging, the results hardly reflect the kind of life-changing reduction his parents were hoping for. It could be that the extract needs more time to take effect or that David needs a bigger dose. Or that the CBD to THC ratio isn’t high enough. Or it could be that David is simply beyond the reach of any treatment.

Ever empirically minded (they’re both Ph.D.s), Tami and Dwight want to see what happens with a longer trial. They will wait a few weeks before they try again, perhaps with the same strain, or maybe something different. Charlotte’s Web won’t make it to Washington until later this year. When it does, they’ll try it. They’re also investigating another option: THC-A extract, or essentially THC that hasn’t been activated by heat. Gedde has seen some success with it in a patient who didn’t respond to Charlotte’s Web, and families in Australia have been using a similar extract for years. It’s still federally illegal, but it’s more widely available than Charlotte’s Web. And it’s another thread for Tami and Dwight to cling to—another of the spidering potential paths revealed by one little Teller County plant. Yet walking down these paths comes with risks; the bone-deep ache of disappointment, no matter how many times it comes, never dulls. “The possible letdown that could come from this not working, after we’d thought we’d been at the end of therapy for years, makes me pretty sad,” Dwight wrote me in an email not long ago. “Still hoping, though,” he adds.

Still hoping.