The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

When my son, Quinn, was three months old, my husband and I gave him a small bottle of milk-based formula. As soon as he polished off a few ounces, he threw it right back up. Within minutes he was covered in hives from head to toe. Thus began his violent allergy to dairy, which lasted well into his teens. While not insurmountable, the constraint was a constant source of frustration: Every home-cooked meal, restaurant dinner out, and bake-sale craving was informed by the strict need for dairy-free options. Then, when Quinn was 12, he inadvertently ate a muffin made with milk—and nothing happened. Not long after, he accidentally ate a cheddar bagel. Cheddar! The lack of reaction seemed inconceivable, considering he would still vomit and scratch at his throat at the slightest sip of cow’s milk.

After the bagel episode, we learned our experience was not an anomaly. Research revealed that certain patients with milk and egg allergies could tolerate the allergens when they had been heated; consuming the baked allergens might just serve as a pathway to desensitization.

Here’s how it works: When dairy-allergic people consume raw milk, their antibodies react to the three-dimensional, tightly folded structure of the milk protein chains. “Cooking alters the proteins in milk and egg so that the proteins unfold,” says Dr. S. Allan Bock, clinical professor of pediatrics and my son’s doctor, who recently retired from Children’s Hospital Colorado. “For some patients, the antibodies no longer recognize the unfolded protein as an allergen.” After a certain period of time—as the person continues to eat baked milk or egg—the antibodies seem to disappear altogether, making it possible for a person like Quinn, for whom the threat of anaphylaxis lurked in every waffle cone, to eat cheeseburgers or whipped cream without incident. Exactly how and why the antibodies disappear, Bock says, remains unclear.

I suppose we experimented, to a degree, on Quinn. He did a baked-milk challenge at Bock’s office, where he sat for four hours eating increasingly larger nibbles of a muffin with milk powder. It was a success, so at home, we cooked pancakes and waffles with milk. After several months, we introduced pizza. It still made his mouth itch at first, but if we broiled an already-baked pizza at home, he could eat it. Eventually, a pie straight from Pizzeria Locale was fine, too.

After three years of eating baked milk and cheese, we had Quinn’s blood tested. His antibody levels to milk had dropped low enough that Bock was willing to try an unheated milk challenge. Quinn sat in the doctor’s office taking bigger and bigger sips—and eventually drinking a full cup—of milk without ill effect. It’s no fluke: Separate studies show that 75 out of 100 children allergic to cow’s milk tolerated heated milk products, and 60 percent of 65 allergic kids who could eat baked dairy worked their way to cold milk.

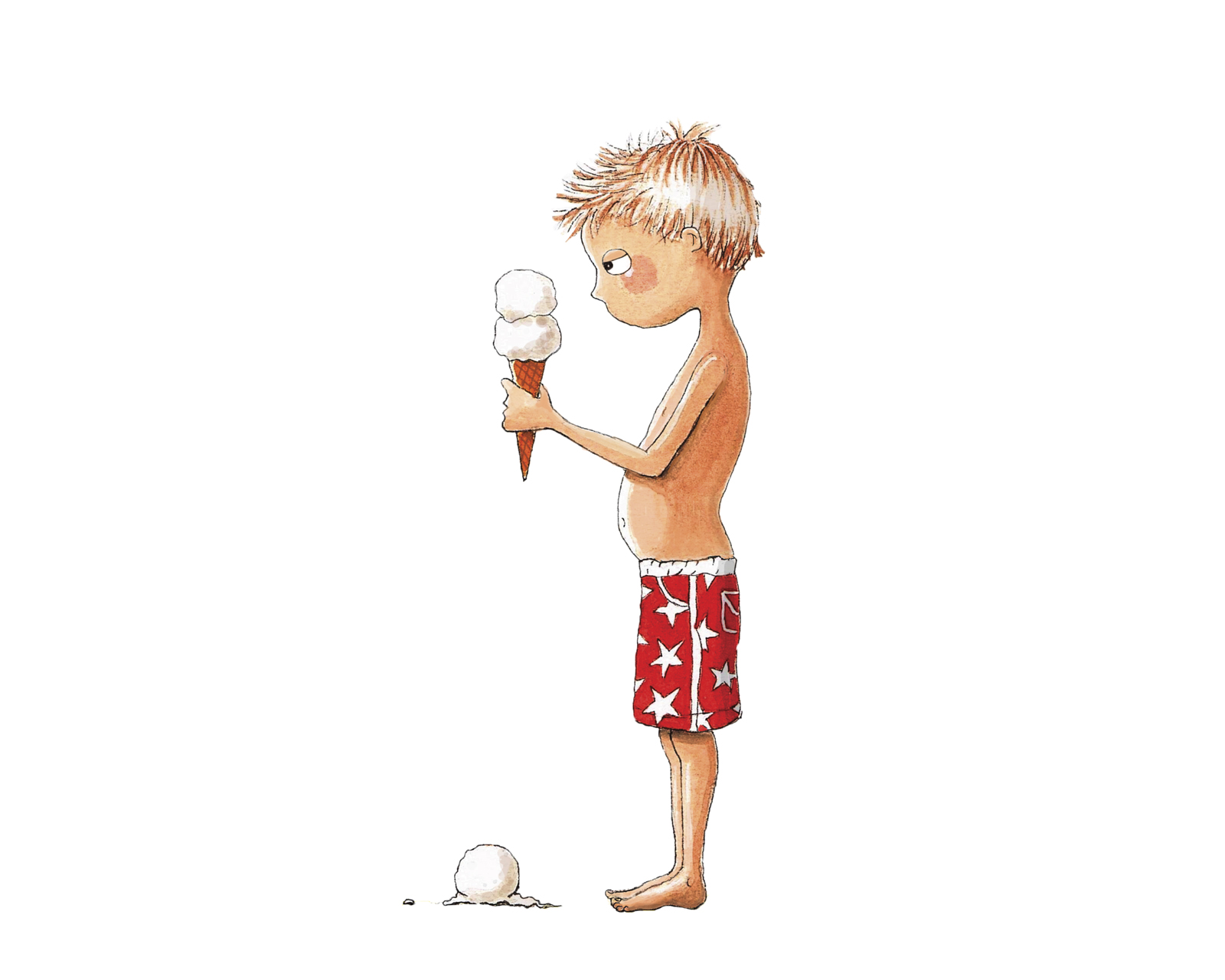

Bock notes that our success doesn’t necessarily mean Quinn is cured. Most allergists agree patients must continue to eat the erstwhile allergen to maintain desensitization. Quinn, now 16, does his part by eating ice cream daily, because—here’s the kicker—he doesn’t even like milk.

By the Numbers

15 million: Americans who have food allergies

8: Percentage of kids who have food allergies

50: Percentage increase in food allergies in children between 1997 and 2011

8–15: Percentage of fatal food anaphylaxes caused by milk

$25 billion: Annual economic cost of children’s food allergies