The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

This article was a finalist for the 2011 City and Regional Magazine Award in the reporting category.

On the evening of August 25, 2008, the first night of the Democratic National Convention, Tamayo was the place to be. The pricey Mexican restaurant on the corner of 14th and Larimer streets, with a canopied rooftop deck and stunning view of the Pepsi Center, was the site of an exclusive convention kickoff party. It was filled with local and national VIPs: Hollywood starlets Rosario Dawson and Jessica Alba mingled among the likes of MediaNews Group CEO Dean Singleton and Virginia Governor Tim Kaine, who would later be appointed chairman of the Democratic National Committee. And positioned in the middle of the first floor was attorney Willie E. Shepherd.

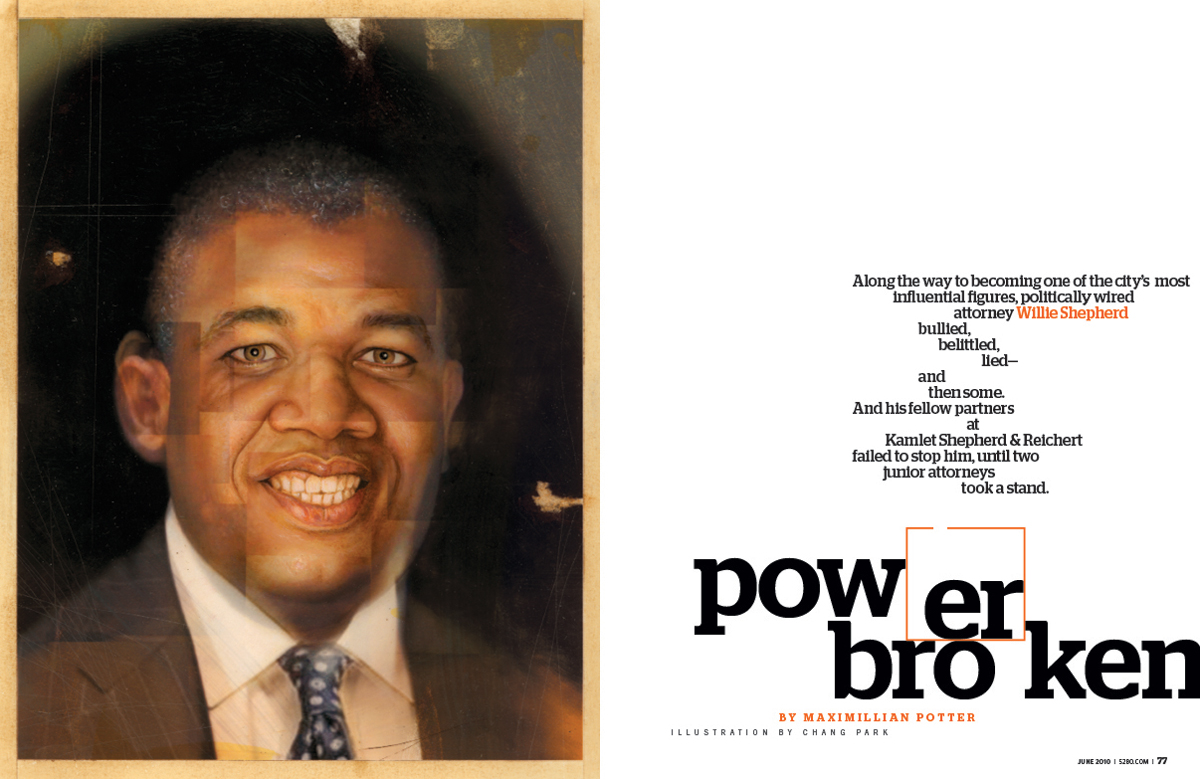

Shepherd was one of the city’s most influential figures and was arguably the most powerful African-American to emerge on Denver’s lily-white power scene since Mayor Wellington Webb. Only months earlier, Shepherd, just this side of 40, had been obese. Six feet tall, he’d weighed 300 pounds. But, incredibly, he’d made a considerable amount of weight disappear. He now looked trim and healthy. He wore a finely tailored suit and shoes polished to a shine that was outdone only by his brilliant smile. If you would have told Shepherd how sharp he looked, he might have responded with one of his signature expressions: “Ain’t nothin’ but a chicken wing.”

The smile, the self-deprecating humor, the good-natured Willie: They were all Shepherd trademarks. His charm made him wonderful company and fueled his success. In the few short years since forming in August 2000, his firm, which became Kamlet Shepherd & Reichert LLP, had grown from a boutique practice of a handful of attorneys into an expanding political and business juggernaut of nearly 50 lawyers, who referred to themselves as “Young Turks.” KSR had managed to recruit well-connected partners, like Ray Gifford, the stepson of Congressman Tom Tancredo, and had siphoned business, influence, and talent away from entrenched 17th Street firms like Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, in part because of Shepherd’s one-of-a-kind Willie-ness.

Whereas elder statesmen of the Denver legal community, like Norman Brownstein and Steven Farber, tend to discretely draw business into them, over, say, breakfast at the Brown Palace, Shepherd wooed—hunted—clients. He networked on the political and charity circuits, but he could be at his ingratiating best over drinks at the Capital Grille, or while picking up the tab for lap dances at the Penthouse Club. It wouldn’t matter to Shepherd if he were on the phone pitching his firm to a Fortune 500 company; according to two former colleagues, he wouldn’t think twice about saying, “Give a brother a chance.”

Shepherd and his fellow KSR founding partners, Jay Kamlet and E. Lee Reichert, cultivated the sort of client list it would take most any other startup firm decades to develop: Molson Coors Brewing Company, CBS Outdoor, Phillip Anschutz’s AEG Live, Xcel Energy, and the city and county of Denver, among others. KSR had a D.C. office and was in talks to handle some work for the blue-chip conglomerate DuPont. KSR’s top attorneys ascended to power-broker status, most notably Reichert and Shepherd.

Republican Governor Bill Owens appointed Reichert, a corporate attorney, to the Colorado Securities Board. Under Democratic Governor Bill Ritter, Reichert rose to chair that five-member panel. Additionally, Reichert took on the prominent philanthropic duty of vice chair of the Colorado Children’s Campaign. Shepherd’s portfolio of involvement was more diverse. He sat on boards of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce, Colorado Concern, and the Colorado Symphony Orchestra, to name a few. In 2008, as the convention loomed, he was named one of the city’s top attorneys by the Denver Business Journal and his legal peers selected him as a Colorado Super Lawyer, published annually in 5280. He was tapped to take on one of the most critical roles of the city’s Convention Host Committee—finance chair—and joined the Obama Presidential National Finance Committee.

Even if you hadn’t recognized Shepherd upon entering the VIP bash at Tamayo, you likely would have pegged him as a somebody, maybe the host, which would have been fine by him. Never mind that the party was cosponsored by Maker’s Mark Bourbon and GQ magazine. Never mind that it was Barack Obama as a “Man of the Year” on the GQ cover poster on display. As Shepherd would make clear days later while dressing down one of his subordinates, he regarded this convention to be his moment. This was the time, he told colleagues, when he would make the jump: Maybe he would be appointed Colorado’s U.S. attorney; maybe he’d get a seat in Obama’s cabinet.

But there would be no lofty political appointments for Shepherd. Much of his persona, his chauffeured SUV, even his new physique were all part of a façade. Soon, two attorneys that worked with Shepherd would expose the real Willie E. Shepherd Jr. In time, the scandal would transcend the man at the center of it all. It would raise a Pandora’s box of troubling questions: about the ethics of some of Shepherd’s fellow KSR partners, namely Kamlet and Reichert; about how the Colorado Supreme Court polices the state’s lawyers; and about the way the town’s establishment does business. As one well-placed source would put it, “It’s not Watergate, but it’s as close as Denver’s going to get.”

II. HAPPY BIRTHDAY

Lukas Staks is a bespectacled, serious-minded young attorney from Utah. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Utah and finished in the top 10 percent of his class at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law. Staks is not the type of guy inclined to think he’s having an out-of-body experience. But on the morning of February 27, 2009—six months after the convention left town—as the associate attorney stood in Willie Shepherd’s office, it occurred to Staks that this must be what people meant when they talked about such a phenomenon. Physically, Staks was in Shepherd’s expansive corner office, with its custom wood walls, flat-panel TV, bar, and bank of windows that provided a breathtaking view of downtown. He was there with the other associate in the firm’s environmental division; Willie’s assistant, Stephanie Wilson; and the boss himself. It was, as Staks had just been reminded, Shepherd’s birthday, and like the rest of his colleagues the associate was now eating a slice of the birthday cake Wilson had baked and making the obligatory chitchat. Mentally, though, he was in another place: All he could think about was what his colleague, Rebecca Almon, was doing at that very moment elsewhere in the KSR offices.

Almon was a non-equity partner. She reported directly to Shepherd, oversaw the environmental associates, and served as a liaison for the group’s clients. A mother of three little girls, she had managed to become one of KSR’s top billers. While Staks was milling about Shepherd’s birthday celebration, Almon was delivering a scathing memo about Shepherd to two of the firm’s equity partners. Staks and Almon had been up late into the night the previous two evenings preparing the document, bolstering each other’s resolve, reading the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct, telling each other it had to be done. The memo read like a multicharge indictment. Upon delivering the document, Almon would quit, effective immediately.

Staks heard someone in Shepherd’s office wish him a “Happy Birthday,” and Shepherd said something about not feeling so happy. Shepherd’s melancholy stunned Staks. No matter what he and Almon had conveyed to senior partners in the previous months about Shepherd’s conduct, it didn’t seem to matter. Shepherd seemed gleefully oblivious. If anything, he’d become more unethical, more egomaniacal, and more volatile, capriciously dismissing three widely respected staffers. Only days earlier, when legal administrative assistant Robin Bissantz informed Shepherd she did not have time to take notes in a meeting for him because, as she told him, she was working on a time-sensitive motion for another partner, Shepherd had canned her within the hour. He personally escorted Bissantz to the human resources administrator’s office. Bissantz told Shepherd what many KSR employees were aching to say: “You have a big-ass ego. If you don’t stop treating this company like your own personal piggy bank, you’re going run this place into the ground.”

The tepid birthday celebration dissipated. Shepherd remained in his office, and the group adjourned to the interior of the 16th floor. Staks sensed a strange mood in the air. The associate heard the elevator doors opening and closing. It occurred to Staks that the distinct ping-pinging of the elevators was happening with a feverish frequency. Within a few minutes, Staks watched Shepherd emerge from his office with a look of concern and ask the receptionist to page Kamlet. Mr. Kamlet was not responding. Try Reichert, Staks heard Shepherd say. Mr. Reichert was not responding either. He had the receptionist try them again, and, again, nothing. Staks saw the look on Shepherd’s face morph into what appeared to be angst. The strange mood, the ping-pinging of the elevators, the unanswered calls—Staks surmised that Almon had done as the two of them had planned, and the senior partners were leaving the building to decide what, if anything, to do about Shepherd.

Within the hour Staks’ cell phone rang. He raced into an empty conference room and answered. During the previous week, as he and Almon had been crafting their memo, the two attorneys had been interviewing with a handful of Denver firms. The day before, Almon had accepted an offer from Ireland Stapleton Pryor & Pascoe, and she’d told Staks that it looked like the firm would also hire him. The call confirmed that. Without discussing salary, he accepted. On that Friday morning, the only question the 29-year-old associate asked was when he could start.

Staks had cleared his casework in anticipation of this very moment, though he was never quite sure it would arrive. KSR’s human resources director was not in her office, and he couldn’t find a senior partner. Staks walked the halls until he finally found an attorney. Staks informed the attorney that he was quitting. Never again, he thought, would he have to abide a lawyer who engaged in the activities he and Almon had witnessed. While Staks phoned his wife and shared the news, Kamlet and Reichert, along with most of KSR’s top partners, gathered off-site and finally summoned Shepherd.

III. THE BEGINNING

It started out small, and it was easy enough for Staks to rationalize it away. In the fall of 2007, Staks had been at KSR for about a year when he was asked to write client-bill cover letters. It is a common practice for lawyers to prepare letters explaining charges to clients. Going over the tally for the municipality of Kansas City, for matters in which he had been involved, Staks noticed “a lot of activity on Shepherd’s bill that I just didn’t see occur.” Staks saw that his own time had been accurately recorded: a couple of hours here, a couple of hours there, at his hourly rate of $175, spent preparing documents. But according to Shepherd’s hours, it appeared to Staks that it had taken Shepherd far longer than it should have to review related documents. Staks was new to the real world, but he wasn’t naive. Attorneys make mistakes tallying their registers. In the end, it all balances out. The first-year associate wrote the letter and went about his business.

Over the course of the next few months, however, Staks paid closer attention to Shepherd’s bills. In virtually every statement Staks inspected, he spotted charges that seemed excessive or unwarranted, discrepancies that only a lawyer privy to the casework could easily detect. For review of routine one-paragraph documents, Shepherd would bill for a quarter of an hour. For three such documents that each would require most lawyers, especially seasoned ones, just minutes to review, Shepherd clocked up three-quarters of an hour, and so on, bill after bill. For one client, Shepherd charged billable hours for meetings that Staks was certain Shepherd had not attended, and, as far as the associate could see, added time for business that had nothing to do with another client.

“Bill the shit out of it” was a mantra Shepherd repeated to the attorneys in his environmental division. Having reviewed months of Shepherd’s statements, Staks became convinced that what Shepherd meant was to fabricate hours. By early 2008, Staks believed what he had seen added up to a systemic pattern that could not be accidental, or, given Shepherd’s hourly rate of about $450, financially negligible. The associate believed he had to present his concerns to his superior in the environmental division.

Rebecca Almon is a tall, fast-moving, fast-talking 42-year-old, with a freckled face and reddish-colored hair. She attended the Chicago-Kent College of Law on scholarship. After graduating on the dean’s list, she worked in private practice and then joined the Illinois Attorney General’s Environmental Enforcement/Asbestos Litigation Division. She loved the work, but six years into her career the Almons had their first child, and Almon opted to be a full-time mom. Soon the couple had three girls, and in 2002 they moved to Denver seeking a better quality of life for the family. Almon’s husband, Joe, had recently started a new business, and with a decrease in earnings and an increase in expenses, he looked his wife’s way and said, “Hey, didn’t I marry a lawyer?”

After eight years away from practicing law Almon took the bar review class. A neighbor arranged her first interview in Denver, with Willie Shepherd. She so impressed Shepherd that the very same day he extended the offer. As an associate, Almon was assigned to Ginn Resorts. Edward Ginn was attempting to turn the defunct Eagle Mine, just southwest of Vail, into a ski resort. Because the mine was a Superfund site, the matter was complex and high-profile. By 2007, Almon’s efforts had so impressed Ginn that the client demanded she be made the lead attorney on the matter. That same year, Almon earned non-equity partner status and became one of the top billers at KSR.

Part of the reason she had been handed such a nuanced case and was able to so quickly distinguish herself, according to several former KSR partners and employees, was because Almon knew more about environmental law than Shepherd. He was not a particularly skilled practicing attorney: When it came to actual casework, according to staffers who worked with Shepherd, he was the managing partner with no clothes. Almon and her associates didn’t much care if Shepherd wasn’t a big help when it came to casework. He was extremely skilled at wooing clients. Now, though, in early 2008, Staks was telling Almon that Shepherd appeared to be stealing from their clients. Almon ran her hands through her hair and in a tone that conveyed billable hours isn’t the half of it, she shared something she had been keeping to herself, something she’d been hoping was an anomaly and would go away.

Almon informed Staks that Shepherd had lied to a Fortune 500 company in order to get business, going so far as to ask her to create what she remembered him calling a “dummy corporation.” Delaware-based DuPont was shopping for minority-owned firms to handle some of its business. KSR had not been minority-owned since 2001, when Shepherd and Kamlet recruited Reichert and divided the firm equally among themselves. Nevertheless, Shepherd informed DuPont that KSR qualified for the “diverse-legal supplier network” and instructed Almon to create the dummy corporation, in which he would be the majority shareholder. Almon told Staks that Shepherd had said simply, “Make it so.”

{C}

IV. TRANSFORMATION

At lunchtime, according to former employees, it was not unusual for Wille Shepherd to plop his 300-pound frame into a chair at the conference table in his office and dig into a meal big enough for two people. He favored the Capital Grille and would have an underling fetch a take-out order that would look like two steaks, a side of something, and a bowl of French onion soup. Often, he insisted that his two assistants join him. In his view, according to several former KSR employees, such companionship, along with unflinching loyalty, was part of what subordinates were paid for. Shepherd tended to talk as he chewed, spraying spittle and dropping food from his mouth. It was not unsual for him to want an afternoon snack, and he would occasionally send someone to Johnny Rocket’s to pick up a hamburger and French fries. Toward the end of 2007 and into 2008, Shepherd had a voracious appetite, for many things.

As Staks and Almon were discovering what struck them as Shepherd’s ethical violations in early 2008, the city was transforming itself for the Democratic National Convention. So, too, was Shepherd. He wanted to present himself as someone worthy of a position with the presidential candidate’s team of advisers, and ultimately worthy of a spot in the Obama administration. He had been telling colleagues that what he wanted was a Cabinet seat, ideally secretary of energy.

To improve his public profile, Shepherd had become the city’s Convention Host Committee finance chair, and promised to raise $150,000 for the Obama campaign’s Obama For America (OFA). To help with the fund-raising obligations and the coordination of related events, Shepherd had felt it necessary to marshal more resources. He hired a second assistant. To a Stephanie Wilson, he had added a Stephanie Estabrook. Some of Shepherd’s colleagues only half-jokingly observed that with two assistants he was even harder to reach. Wilson primarily handled Shepherd’s traditional workload, and Estabrook and the firm’s marketing manager, Terri Taylor, aided with convention-related endeavors.

Shepherd always seemed to be running here and there, meeting with this CEO and that tycoon for the fund-raising. But, according to several sources involved with his convention activities, he often left it to others to do the work. During a trip to D.C., according to a well-placed source, Shepherd missed a morning meeting with potential corporate donors, leaving his underling, Taylor, and a staffer from Senator Ken Salazar’s office to make nice. As the deadline for OFA approached, it became evident that Shepherd was well short of raising $150,000. According to sources familiar with the fund-raising, it was Shepherd’s relatively new hire, the twentysomething Estabrook, who would regularly make calls to potential donors; she was the one left to forge relationships with the OFA grassroots team and to work with them to “find” anonymously made donations that could be credited to Shepherd. None of that, according to a Denver-based Obama campaign worker, prevented Shepherd from prominently featuring his name on the promotional materials for a party for donors, which, the source says, angered Bruce Oreck. Now the U.S. ambassador to Finland, Oreck made his fortune in the family’s vacuum cleaner business and had sucked in at least $500,000 for OFA.

While Shepherd was aggressively trying to beef up his public persona, he decided to undergo gastric bypass surgery. He walked into the office of a KSR administrator, and, according to the now former administrator, announced his desire to have the procedure. He was expecting the firm’s insurance company to cover the cost, the former administrator says, and when he was informed that there was a process for such surgeries—and even then it likely wouldn’t be covered—Shepherd berated her. According to the former firm administrator, Shepherd screamed at her, “I founded this firm. I built it up from nothing.” In the end, according to the former administrator, KSR’s insurance plan did not pay for the surgery. Before the procedure, it was big meals from the Capital Grille and Johnny Rocket’s; after the surgery, Shepherd’s diet included yogurt and black beans.

Considering the convention chaos, Staks and Almon decided that this was no time to voice their concerns about Shepherd. No one, they concluded, would have time to listen to, or want to hear, what they had to say about the firm’s chairman and managing partner, the finance chair of the Convention Host Committee, a fund-raiser on OFA. Truth be told, the two attorneys hoped that Shepherd would get a plum political appointment and would be out of the firm, and out of their lives, forever.

{C}

V. “STIR THE POT”

During the convention, one of assistant Stephanie Estabrook’s many tasks was to manage Shepherd’s allocation of VIP tickets in accordance with his wishes. Managing and bartering the finite number of tickets and reconciling it all with Shepherd’s expectations, according to former staffers, was nearly impossible. Estabrook was not only responsible for most of that, but Shepherd also demanded that she hold his credentials and come running whenever he needed them.

The night of Obama’s acceptance speech at Invesco Field at Mile High, Shepherd became irate that Estabrook did not get his credentials to him soon enough, even though, as Shepherd had ordered, she had been busy escorting a VIP through security. That evening, in front of a gathering of guests, Shepherd told Estabrook she was dumb and that it wasn’t working out. He fired her. The next day, Friday, Estabrook went to the home of the firm’s marketing manager, Terri Taylor, with whom she had been working closely, looking for support. As Estabrook informed Taylor about what had happened, one of them inadvertently called Shepherd from Estabrook’s mobile phone. Shepherd overheard part of their conversation, and within a couple of days, Taylor, too, was no longer with KSR.

Shepherd’s blow ups with Estabrook and Taylor became the stuff of legend at KSR, and, according to several of the firm’s former attorneys and employees, unnerved the staff. Staks and Almon weren’t sure if these developments made it a better or worse time to come forward. Then, the situation changed for the worse. Staks noticed that Shepherd had apparently falsified his biography on the KSR website. As far as Staks and Almon could tell, Shepherd was mischaracterizing his work experience.

There was more. Shepherd attempted to undermine one of his own clients, or so it seemed to Staks and Almon. CBS Outdoor, one of the region’s largest outdoor advertising companies, was fending off a competitor’s challenge to CBS’ claims to some of its long-held billboards. The competitor alleged that CBS’ city-approved permits to 27 signs, worth some $2.2 million in annual revenue, were out of order. In a meeting in September 2008, at which Staks was present, CBS Outdoor executive Dan Scherer discussed with Shepherd resolving the issue. Shepherd suggested calling the city and asking them to check the permits.

Scherer, as Staks would recall, was adamant that he “did not want to wake the sleeping giant,” meaning he did not want such a call to be placed to the city, and Shepherd agreed KSR would explore other strategies. Nevertheless, the next day, according to Staks, Shepherd directed him to call the city agency and have the permits examined. Staks, as he would recall, asked Shepherd for clarification: did Shepherd want him, despite the client’s comments, to call the city? Shepherd said to Staks, “I am telling you to stir the pot.” There was no other reason for Shepherd to directly go against the client’s wishes, as far as the associate could tell, other than to drum up billable hours. Staks turned to Almon, who told him what he already believed to be the case: Under these circumstances—a permitting issue—the firm had an ethical and professional obligation to follow the client’s wishes.

Together, the two attorneys decided that Staks would not act on Shepherd’s directive; instead he would e-mail Shepherd and ask him if he was certain he wanted the associate to ignore what Scherer had said. If Shepherd would confirm this in writing, that would add to what Staks and Almon regarded as a body of evidence they planned to take to the senior partners. On September 17, 2008, at 1:01 p.m., Staks sent Shepherd an e-mail with the subject heading “Stirring the pot,” asking him to confirm the order. Weeks passed without a response.

The craziness of it all, Staks and Almon now believed, had to be addressed, and the two attorneys decided it was time to talk to another senior partner. That September, Almon went to equity partner Ray Gifford. Both Almon and Staks regarded Gifford as an upstanding attorney and a good guy. They knew also that Gifford was a close friend of Lee Reichert. Their families had shared a condo in Winter Park, and Reichert had persuaded Gifford to join KSR. In talking to Gifford, Almon figured, she could diplomatically communicate her concerns to Reichert. Gifford was deeply troubled by what he heard, and that same day set up an off-campus meeting with the two junior attorneys, himself, and Lee Reichert.

{C}

VI. MEETING AT THE MARKET

The four lawyers sat around a table at the Market at Larimer Square. Staks and Almon shared their concerns about fraudulent billing. They said that Shepherd had tried to improperly break a contract with a legal temporary employee agency, named Special Counsel. Reichert said: You don’t want to handle administrative matters; we’ll take care of that. Staks said he didn’t have a problem with administrative tasks; he believed Shepherd was behaving unethically and appeared to be fabricating charges. Staks and Almon told Reichert they were concerned that Shepherd was misrepresenting his client-work history in his bio on the firm website; that Shepherd was claiming expertise that the two lawyers believed he did not have. Staks and Almon were left with the impression that Reichert would look into it.

Staks reported to Reichert the “stir the pot” incident. Reichert asked Staks if he had in fact called the city, and Staks said no. In that case, Reichert was of the mind that no breach of client duty had occurred. Almon brought up Shepherd misrepresenting the firm as minority-owned. Staks and Almon got the impression that, moving forward, Reichert was going to keep an eye on that. There was a general acknowledgment that Shepherd had been tyrannical with employees, including Estabrook and Taylor, and then the meeting adjourned. Almon and Staks had expected more of a reaction from Reichert—after all, Reichert was a cofounding partner with the reputation for being ethically impeccable. He was also the chairman of the Colorado Securities Board.

Staks, alone, returned to Gifford’s office after the meeting for his take. He informed Gifford that the situation had become so intolerable for Almon and himself that they’d begun looking to join another firm. If you stay here, Gifford told Staks, I don’t think this will end well for you. Gifford added that if Staks needed a reference, he would be happy to attest to the fact that the associate was a talented, ethical attorney.

{C}

VII. POTENTIAL CONFILCTS

After the meeting at the Market, nothing about Shepherd’s behavior visibly changed, according to several sources. If anything, it got worse. Shepherd again asked Staks to alert the city to CBS Outdoor’s possible permit issues. In early October, Staks says, Shepherd responded to the “Stirring the pot” e-mail by telling Staks to do as he was directed and to not put anything like that in an e-mail again. Staks continued to not call the city. Then there was a conflict of interest that Shepherd seemed to ignore.

Shepherd represented AEG Live, Rocky Mountain Region, the music and sports subsidiary of the Anschutz Entertainment Group (AEG). Legendary concert promoter Chuck Morris is the president and CEO of AEG and had much of his legal work done by Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, where Steven Farber was an old friend of Morris’.

However, Morris had met Shepherd at charity and political fund-raisers and liked the guy. He liked that he was a minority lawyer on the rise, and he wanted to give the up-and-comer a try. On the heels of the convention, Morris liked that Shepherd appeared to be at the center of the action—and that he was willing to work for free. In order to get in the door with AEG, Shepherd agreed to handle some business at no charge, which is not an uncommon way for a law firm to audition for a large client. The AEG audition was this: Morris was interested in acquiring the lease on the Denver Coliseum from the city and county of Denver. A consequential side note was that Morris had struck an arrangement with Dan Scherer of CBS Outdoor that would allow the company to post signage at the venue.

Because the Coliseum is within a Superfund site, this was not a typical lease arrangement. There were potentially costly issues of liability. Complicating things was the fact that KSR represented some of the city and county of Denver’s bond work. Complicating things even further were the issues between the city and CBS over the sign business. Shepherd and his firm represented all of the parties involved, which could be a conflict of interest, yet in April 2008, when Shepherd logged this business into KSR’s internal “New Client/New Matter List,” which requires the attorney to identify any potential conflicts or “adverse parties,” he listed “None.”

Almon took her concerns about this matter to senior partner Stephen D. Gurr, who was considered the firm’s ethics guru. He confirmed what Almon knew: It would be permissible for Shepherd to represent all three parties if the firm obtained written waivers that clearly explained to all three parties the nature of the representation. The waivers had to be signed by all parties involved. In legalese this is called advance consent. Almon conveyed this in an e-mail to Shepherd on November 17, 2008, at 2:13 p.m. Two minutes later, she forwarded the e-mail to equity partner Brian Jumps.

About that time, Staks and Almon again noticed that Shepherd had amended his website biography. Shepherd, who, according to several sources, was hoping President Obama’s administration would consider him for a position, now included in his bio on the firm’s website that he served as the cochair of the transition teams for Governor Bill Ritter and Mayor John Hickenlooper. A Google search would show that Shepherd was not listed as a ranking member of those transition teams, let alone one of the people in charge of both of them.

By February 2009, Almon and Staks had made at least two senior partners—Ray Gifford and Lee Reichert—aware of their concerns. Yet Shepherd continued to operate seemingly unchecked. Likewise, when Shepherd blew up on Estabrook and Taylor, and much more recently and dramatically, fired Robin Bissantz, in February 2009, none of the senior partners took any visible action. However, on the office grapevine there was word that the senior partners were concerned about Shepherd. Rumor was that Gifford had agitated for change, and that there would be a partner meeting at which a new tone, a new world, would be introduced, wherein Shepherd and his ways would be reined in.

The meeting occurred on Wednesday, February 25, 2009, in the KSR conference room. It was a partners-only gathering—associates like Staks were not invited—and all but a very few of the senior partners were present. Shepherd took a seat next to Almon, and he was the first to address the gathering. According to sources who were at the meeting, Shepherd said it had been a tough year, but the firm was well-positioned. He talked about how the politics favored KSR, giving them an edge here and an edge there. He mentioned that new clients had come on board. Partner Brian Jumps interjected that Shepherd himself had brought in DuPont, and initiated a round of applause. Seated at the other end of the table from Almon was senior partner Fred Winocur. Shepherd and Winocur had attended law school together at Tulane University. It was Shepherd who lured Winocur to KSR from the Denver firm of Haddon, Morgan and Foreman (HMF). In the meeting, Winocur, according to the sources present for the meeting, talked about rumors that had been circulating the office, and said that moving forward, the rumors needed to stop.

Following the meeting, Shepherd, Kamlet, and a few other partners left for a dinner, and Almon told Staks what had transpired at the meeting. The two attorneys went to Staks’ house and crafted the memo that, they believed, laid out the dates, details, and supporting documentation of what they had discussed formally and informally with various partners in the preceding months. Two days later, on Friday, February 27, 2009, while Shepherd was having his cake, Almon delivered the surprise memo to Ray Gifford and Brian Jumps.

{C}

VIII. SHEPHERD MUST GO

In less than two hours, Gifford was seated at a table in a room at the Lakewood Country Club, where Jumps was a member. The gathering was comprised of equity partners. In addition to Jumps and Gifford, the group of KSR attorneys included Reichert, Kamlet, and others. According to one of the attorneys present for the gathering, Stephen D. Gurr was teleconferenced in, and Winocur arrived later. The discussion was heated. The majority of those in attendance were of the mind that Shepherd had to go, and some conveyed that it was either him or them. Whatever delay there was in achieving quorum was caused at least in part by Jay Kamlet. Shepherd was far more than Kamlet’s fellow founding partner. He considered Shepherd an adopted brother, and in Kamlet’s world such a bond was sacrosanct.

Before KSR, Kamlet was a partner at Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck (BHFS), and Shepherd was a lawyer with Patton Boggs, a Washington, D.C.-based firm with an office in Denver. Both were in their 30s. Kamlet handled real estate and leasing matters; Shepherd focused on environmental and land-use law. Thanks to ties to Mayor Wellington Webb’s administration, Shepherd had developed a strong book of business. And Kamlet: His pedigree in Denver was platinum. He was much more than a typical partner at BHFS.

Although “Kamlet” was not a name on that firm’s door, the family loomed large in the history of the formidable practice. If it weren’t for Kamlet’s family, it’s likely that BHFS would not exist. When Norman Brownstein was a boy, his mother moved with young Norm to west Denver. They settled there because it was home to the National Jewish Hospital at Denver, the entity that would become National Jewish Health. Mrs. Brownstein found medical care, and she and her son discovered an extended family in Denver’s Jewish community. It was in west Denver that a fifth-grade Norm befriended schoolmate Steve Farber. In 1957, when Norm was about 13, his mom died from breast cancer, and the Kamlet family, Stan and his wife, took Norm into their home, raising him as if he were one of their own. Jay Kamlet, Norm’s “little brother,” wasn’t born until 1963, just as Norm and his childhood pal, Steve, were on their way to the University of Colorado and law school. In 1968, when Brownstein, Farber, and a law school friend, Jack Hyatt, launched their own firm, Jay’s mom—Brownstein’s surrogate mom—was more than the firm’s first secretary; she was the chief founding den mother. It was Mrs. Kamlet who literally held the straws that the partners drew to determine the order of names as they would appear in the firm’s moniker.

When Kamlet decided to follow his big brother into law, he did so with Brownstein’s support. Likewise, after Kamlet had worked a few years with a D.C. firm and asked to join his big brother’s operation, he was welcomed as a partner. For years, Kamlet watched as his big brother and Farber emerged as Denver power brokers, schmoozing, donating, strategizing—harnessing the confluence of politics, business, and law—and ultimately profiting. As Kamlet put it to Farber in 1999, when the young partner informed Farber he was leaving the mother ship, he and Shepherd believed they could become the next Brownstein and Farber.

The idea of forcing Shepherd out of the firm they’d built couldn’t have been easy for Kamlet. And that afternoon at the country club it only got more difficult, more dramatic. A call was placed to Shepherd, and he arrived around 4 p.m. As the partners informed him of the memo, according to a lawyer who was present, Shepherd quickly sensed where the conversation was going and said, “You want me to go.” Shepherd vacillated between fury and sobs. There was a discussion about how to handle Shepherd’s departure. An understanding was struck: Shepherd would voluntarily leave, and he would manage whatever press there would be about his departure. Shepherd would assist the firm, which would rechristen itself Kamlet Reichert LLP (KR), with doing whatever was necessary to rectify whatever needed to be rectified.

Shortly after the Lakewood meeting adjourned, Shepherd’s former firm made two moves. A representative of the practice called Fred Winocur’s old employer, Haddon, Morgan and Foreman P.C., and hired the firm to assist KR in reacting to the memo. One of the senior partners instructed an administrator to not only cancel Shepherd’s access card to the firm’s suite, but also to stop elevator access to the offices for everyone except employees. Kamlet, and some of the partners were concerned, according to a firm administrator, that Shepherd might attempt to return to the office, and if that were to happen, feared what he might do. Another benefit to cutting off elevator access was that no one at the office would need to worry about a reporter arriving with questions.

Shepherd and his former firm kept the situation quiet for the next two and a half months. On May 12, 2009, the Denver Post published an article headlined: “Willie Shepherd leaving Kamlet Shepherd & Reichert.” There was no explanation why Shepherd was leaving the firm he’d cofounded, no mention of where he’d be going next. Nine months after the convention, there wasn’t the slightest hint of a bigger or better move. The article quoted two sources: Shepherd said he was “looking forward to the future and to helping serve Denver and Colorado.” On behalf of Shepherd’s former firm, Reichert said, “We are thankful for the leadership that Willie has provided to the firm since its inception and wish him well as he moves forward.”

The next day, the Denver Business Journal reported that Shepherd was joining the law firm of Perkins Coie as a partner. A managing partner of Perkins Coie was quoted as saying that, “having an attorney of Willie Shepherd’s caliber reflects our strength as an expanding national law firm.” Then, on May 16, news broke that Perkins Coie had rescinded its offer. In a statement, the firm said that Shepherd’s “offer was subject to a number of conditions, some of which could not be satisfied.” Embedded in the head-scratching news was the statement that the managing partners of Kamlet Reichert declined to comment on reports of a “complaint pending against Shepherd” before an entity called the Office of Attorney Regulation Counsel.

IX. THE COMPLAINT

Colorado attorneys must adhere to the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct, which state precepts such as, “a lawyer shall abide by a client’s decisions concerning the objectives of representation,” and that it is a violation to “engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation.” The Colorado Supreme Court is responsible for enforcing the rules, and it relies on the Office of Attorney Regulation Counsel (OARC) to investigate allegations of misconduct and then either dismisses the matter or determines it can prove the allegations “by clear and convincing evidence.” The OARC has the ability to subpoena witnesses and records. It does not, however, make disciplinary decisions on its own. If the OARC determines there is probable cause for a case against an attorney, it presents its case to the Attorney Regulation Committee.

Comprised of six attorneys and three nonlawyers, all volunteers recruited from around the state and appointed by the state Supreme Court, the committee acts as a grand jury. The members review OARC’s case and either accept or reject its request for “formal proceedings,” which means a trial held before a three-member panel. The OARC can make other disciplinary recommendations, such as dismissing the allegations, privately reprimanding the attorney for minor offenses, imposing a form of diversion such as ethics training, or, for offenses the OARC believes merit something more severe than a private reprimand, it can suggest the attorney be publicly censured. Even if the committee agrees that a trial is in order, the OARC has the power to enter into mediation, essentially a plea bargain, with the attorney in question.

On May 7, 2009, more than two months after Staks and Almon left KSR, they jointly filed a complaint about Shepherd with the OARC. The seven-page letter was a refined version of their original memo to Ray Gifford and Brian Jumps. In language tailored to the specifics of the Rules of Professional Conduct, Staks and Almon laid out how the two attorneys believed Shepherd had violated at least a half dozen rules. The official allegations included: “breach of duty of client loyalty,” “failure to obtain or report conflicts of interest,” “misrepresentation generally,” “misrepresentation of personal history and legal clients,” “billing practices,” and “fraud, theft, and misuse of firm money.”

The latter accusation stemmed from information the two gleaned while working with Shepherd’s former assistant, Stephanie Estabrook. According to Estabrook, Shepherd had her fabricate invoices from charities for donations Shepherd said he’d made. Shepherd would then have an assistant immediately take those invoices to the firm’s financial administrator and demand to be reimbursed. Estabrook shared with Staks and Almon that, around August 2008, the month of the convention, Shepherd had her fabricate two invoices from the Colorado Symphony, each for $7,000. Estabrook said that he had her copy the format from the symphony’s website. Estabrook became so concerned that this was wrong that she saved the invoices on her office hard drive; she’d added letters to the “invoice” numbers in order to distinguish them from authentic ones.

Staks and Almon delayed filing their complaint for several reasons: There was the practical endeavor of trying to assimilate into their new jobs at Ireland Stapleton. Also, as Staks says, after Almon delivered the February 27 memo to the partners, the two lawyers figured there was no way their former firm would not report Shepherd to the OARC. If the firm reported Shepherd, Staks and Almon figured they would have done their part and justice would be done. And there was this: When Almon left KSR, she entered into talks regarding a severance agreement with the firm. According to Staks, Almon signed a separation agreement that not only precluded her from saying anything disparaging about the firm, but also precluded her from going to the OARC with a complaint, unless she was advised to do so by an attorney. According to Staks, Almon agreed to this point reluctantly, and only after being assured by the firm that it would deal with Shepherd.

On March 24, 2009, about one month after Staks and Almon quit, KSR sent a letter to OARC that was signed by the firm’s chief legal officer, Stephen D. Gurr, and by Willie E. Shepherd. The letter read: “On behalf of Kamlet Shepherd & Reichert, LLP, I am making this report pursuant to RPC 8.3. This report involves the actions of Willie E. Shepherd, Jr. who joins this report as a self-report.” The self-report confirmed that Shepherd had sent an e-mail to DuPont’s legal department “in an attempt to get the firm qualified for DuPont’s Diverse Legal Supplier Network. That e-mail misrepresented the equity ownership of the firm. Mr. Shepherd sent subsequent misleading e-mails in furtherance of the effort to qualify as a minority/woman-owned law firm.” The self-report made a point of mentioning that “the firm recently learned of these e-mails.” There was no mention of any of the other misconduct that Staks and Almon had put in their memo or had discussed at the Market with Reichert and Gifford.

One interpretation of this self-report was that Norman Mueller of the esteemed law firm of Haddon, Morgan and Foreman had completed his investigation into the allegations raised in the memo and had found that this was the only allegation of merit. Another possible interpretation of the self-report was that Mueller’s investigation was not quite as thorough as Kamlet Reichert wanted the OARC to believe. Certainly, that was how Staks and Almon interpreted it. Staks and Almon consulted with an attorney, Marcy Glenn of the firm Holland & Hart, who advised them to file their own complaint.

The Shepherd matter found its way to the desk of the top-ranking official in OARC, the Supreme Court regulation counsel. The regulation counsel, John Gleason, is a lawyer appointed by, and serving at the pleasure of, the court. Before he signed on with OARC as an investigator more than 20 years ago, Gleason was a private-practice attorney. Before becoming a lawyer, he had been a cop and worked in a bomb unit. Gleason was uniquely equipped to recognize the explosive nature of the Shepherd complaint. Assistant regulation counsel Lisa Frankel and investigator Janet Layne were assigned to the matter, and, as he says, “at every turn I was involved” in this case. If the OARC determined there was probable cause for the allegations of misconduct, and it moved for trial, Shepherd could have his license suspended or be disbarred. A trial would be public and might give rise to other questions about who in KSR knew what and when. What’s more, the OARC could inform the district attorney’s office of criminal conduct.

{C}

X. PUBLIC CENSURE

OARC spent nine months investigating the allegations contained in the Staks and Almon complaint. On January 29, 2010, the OARC investigation was officially closed and Frankel and Layne typed up their findings in the “Combined Report of Investigation.” They determined that there was probable cause for the accusation that Shepherd had deceived DuPont with the e-mails, which had been “self-reported.” The OARC also concluded that Shepherd had misrepresented himself with a fraudulent biography and e-mail, specifically to Ray Rivera of Obama’s team. Both of these charges of misconduct violated Rule 8.4: The OARC believed there was clear and convincing evidence that Shepherd “engaged in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation.” Furthermore, the investigators determined “these matters are not appropriate for diversion because of respondent’s dishonesty and the likely outcome is greater than a public censure.” The investigators recommended the “filing of formal proceedings” against Shepherd. In laymen’s terms, the investigators believed that at trial Shepherd would be found guilty of this misconduct and could be suspended or disbarred.

As far as the other allegations went, the OARC concluded it “did not believe it could prove them by clear and convincing evidence and/or did not believe they warranted formal proceedings.” The regulation counsel provided a written explanation to Staks and Almon. The OARC stated that there were only two people involved in the alleged “stir-the-pot” exchange, Shepherd had denied making the statement, and, even if he had made the statement, the OARC would need to prove Shepherd’s intent was to “generate business for the firm at the expense of his client, or that he actually took some action against his client.”

On the conflict of interest allegation, Staks and Almon told the investigators that, shortly after they quit, they had informed Dan Scherer and Chuck Morris why they were leaving the firm. They said both men, especially Scherer, were livid when they heard the scope of the representation matrix Shepherd had involved them in. Both clients promptly cancelled their business with KSR and took their work elsewhere. Scherer, according to the complaint, went so far as to demand “tens of thousands of dollars from the firm due to overbilling.” According to OARC, however, by the time it conducted its interviews with Morris, Scherer, and city attorney David Fine—the would-be victims were fine with the multiple-party arrangement, provided, as Morris put it to the investigators, “the representation was not adverse to his goals.” OARC added that, although Shepherd “did not get the written waiver from AEG, no harm was caused by this conduct.”

Shepherd’s former assistant, Stephanie Estabrook, told OARC investigators she believed Shepherd overbilled. Coupled with Staks and Almon, who provided the OARC with examples of where they believed billing misconduct had occurred, the OARC had at least three former employees, including two attorneys, alleging that Shepherd had engaged in fraudulent billing. Staks, Almon, and Estabrook comprised half of Shepherd’s small environmental division.

Shepherd denied the allegation that he knowingly engaged in fraudulent billing. In a response he submitted to the OARC, he wrote: “Although I have many strengths as a practicing lawyer—especially with client development work and relationships—my administrative tasks such as time keeping and billing need improvement. In retrospect I memorialized my billable time too sporadically. I billed weekly, biweekly, or even once a month. With the help of my administrative assistant Stephanie Wilson I reconstructed my time by using my calendar. That system was inappropriate. It was neither in my clients’ interest nor my firm’s interest.” In her interview with the OARC, Wilson echoed her boss’ explanation. The OARC found that Shepherd could have engaged in better billing practices by recording his time on a daily basis, but, the investigators concluded, they could not prove by clear and convincing evidence that Shepherd fraudulently billed clients.

Although Shepherd admitted to the OARC that he directed an assistant to “create two invoices, for $7500” from the Colorado Symphony, the OARC determined it could not prove that Shepherd’s purpose was to collect reimbursement for his own personal use or that he did collect reimbursement from these invoices. Mueller indicated in writing to investigators that “the first invoice was paid directly to the non-profit entity and that KSR was waiting to pay the second invoice directly to the non-profit entity.” [Mueller] assured investigators that KSR “did not reimburse respondent on either of these invoices.”

Staks and Almon presented the OARC with an e-mail sent to DuPont, which by then had been “self-reported” by Gurr and Shepherd. This accusation, in effect, had already been proven. However, in the complaint Staks and Almon filed, they reported that in addition to the e-mails, Shepherd had instructed that Almon create the “dummy corporation,” which she insisted Shepherd had done to legitimize his lie. The OARC’s position was that the “dummy corporation” was “a sub-firm,” and although Shepherd “agrees that KSR had discussions about setting up a sub-firm” that “alone, does not violate the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct.” Because Shepherd and KSR never actually created “the sub-firm,” the OARC wrote, “we cannot speculate whether a particular sub-firm respondent and the KSR firm might have created would have complied with the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct.”

For the two allegations OARC sustained, the clear and convincing evidence was based on easily obtained, undeniable documentary evidence. Yet in its attempt to obtain evidence for the other allegations, according to what Gleason told me in a recent interview, his investigation stopped with the information supplied by Mueller’s internal “investigation” and witness statements. Gleason, who said he was involved with the Shepherd investigation “every step of the way,” told me that his office did not issue a single subpoena for financial, billing, or any other kind of records from Shepherd or from the firm. The OARC did not subpoena a single witness.

The Shepherd matter never reached a point where witnesses would have testified under oath and been cross-examined, because, in the end, the OARC didn’t abide by its own—committee-approved—recommendation for a trial on the two allegations of misrepresentation. Before the proceedings were initiated, Shepherd and his attorneys entered into mediation with the OARC. Citing attorney regulation protocol, Gleason said he was not able to disclose the nature of those discussions, but this much is certain: On the other side of that meeting, the OARC imposed the sort of punishment that the investigators, according to their report, did not think would be sufficient. The OARC issued a public censure against Shepherd for the two offenses, fined him $127.50 for administrative costs, and allowed him to maintain his law license and practice in Colorado.

In a recent interview, Gleason said that all of what his office did in its investigation was by the book. He told me, “Our presumption is that people tell us the truth. Do I believe they tell us the truth all the time? When I was in private practice, I don’t know that I ever had a client that told me the whole truth, but the bottom line is we have to rely on that.”

So on whom did Gleason and the OARC rely for the “truth”? Dan Scherer and Chuck Morris, a couple of would-be victims? If in their interviews with the OARC, Morris could not recall certain information, and if Scherer held a different opinion of his business at Kamlet Shepherd & Reichert, might it have been because the law firm that he (and Morris) took their business to was Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, which is run by Farber and Brownstein, who consider the Kamlets to be family? Farber recently told me that he advised Scherer to put the KSR experience behind him and move on.

Did the OARC rely on Norman Mueller, whose investigation found merit in one of the allegations? He became Lee Reichert’s counsel and accompanied Reichert to his interview with the OARC.

Did the OARC rely on Reichert? According to OARC documents, Reichert told investigators the discussions KSR had about forming an alleged dummy corporation were discussions about how to form an “entity,” and that those discussions didn’t amount to much.

Did the OARC rely on Shepherd himself? That would be odd, because OARC was already on its way to publicly censuring him—twice—for lying.

Did the OARC rely on Staks and Almon? Gleason viewed their complaint with a certain perspective almost from the start. In Staks and Almon’s allegations, Gleason saw something that led him to believe they were motivated by some kind of vendetta. “Kind of the reality of it is,” Gleason told me, “the nature of the allegations made in this case were extraordinarily personal. I don’t know why. I suspect I know why.” Gleason went on to liken Staks and Almon’s parting with KSR, and Shepherd, to a marriage gone bad: “You have this horrible work environment created by maybe the respondent lawyer, maybe by the complainants, or maybe by [both parties]. They have a horrible breakup, and now we have all of these allegations flying back and forth, and the truth is somewhere in between.”

EPILOGUE

In the nine months I spent reporting this story, I interviewed more than 20 sources, and talked to or otherwise communicated with many others. Jay Kamlet agreed to speak with me, then declined and sent me this e-mail: “There isn’t an event that I attend where someone doesn’t come up to me to let me know that you have contacted and/or spoke with them. I am sure your inquiries have yielded more than enough information about the situation. Any attempt to put my perspective on the story at this point will only come off as defensive.”

Lee Reichert declined to speak with me via e-mail: “Our firm’s ability to answer questions or comment with regard to the potential story you are working on is limited by the ethical rules that apply to all Colorado attorneys, the confidential nature of the Office of Attorney Regulation Counsel process and various agreements we have entered into, all of which we intend to honor. In light of these obligations and our firm policies regarding former employees, we do not believe we can sit down with you at this time. Kamlet Reichert, LLP can provide the following statement: Once our firm received notice of the specific and formal allegations concerning Willie Shepherd, we took immediate action and a thorough and independent third party investigation was immediately commenced and conducted regarding all of the allegations. Following the completion of the independent investigation, it is our understanding that the Office of Attorney Regulation Counsel similarly conducted a comprehensive, many months long investigation into all matters, which resulted in the public censure.”

One of the very first sources I contacted for this story was Willie Shepherd. I called him on his cell phone last summer and explained to him that, in the wake of the news reports of him leaving his firm and the investigation then under way by the Attorney Regulation Counsel, I was going to do a story on him and the investigation. Shepherd said the investigation was much ado about nothing; he said we were “friends;” and he asked me not to do the story.

My “relationship” with Shepherd consisted of running into him socially three times over a period of five years. On the phone, during that first call, I shared my opinion with Shepherd that we were not friends, and I told him I was going to report the story, and I hoped he would cooperate. Shepherd said he wanted to think about it, and a day or two later we spoke again by phone. He said that if I held off on my story until after the OARC had completed its investigation he would sit down and grant me an interview. I specifically asked him if he would honor that promise regardless of the OARC’s findings, and he said yes. Nine months later, after the OARC completed its investigation, I called and e-mailed Shepherd to follow up on his earlier offer to sit down and talk. In an e-mail, he wrote, “I do remember our conversation last year but circumstances have certainly changed since that time. I’m not comfortable getting together to ‘talk’ with you.”

During the OARC process, Shepherd left a good bit of the talking to his attorney, Patrick Burke, who submitted to the OARC a biography of his client as a way of presenting mitigating circumstances for Shepherd’s misconduct. Whatever Shepherd did, the biography says, he did for others, and the sacrifice and hard work caused tremendous stress: “For example, as the first African-American board member for the Colorado Symphony Orchestra, Willie helped implement an outreach program to the Denver Public Schools. Under the program, students who normally had no exposure to classical music were able to enjoy a symphony experience.” He believed he served as a model for younger African-Americans. “Without him, [KSR] would not have achieved anything close to the level of success that it attained.”

Shepherd felt “tremendous pressure” to build and sustain his firm, and this created “pressure for him to succeed” even more with each passing year. He “was instrumental” in bringing the 2008 convention to town. The “pressure to raise money was ever-present.” 2007 and 2008 were “extra-ordinarily time-consuming and stressful for Willie.” Shepherd’s mother developed medical problems—blood vessels in her head were leaking. The pressures “exacerbated his weight problems. He also smoked and drank too much alcohol.” He suffered from sleep apnea, and he had high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, and significant joint pain. Shepherd was “quite literally killing himself,” the bio submitted to the OARC reads. Having “exhausted all other options,” he saw a surgeon and was scheduled for gastric bypass surgery on January 15, 2008. “That Willie accomplished so much under the circumstances is a testament to his innate abilities and the fundamental soundness of his character.”

Many of the sources I spoke with were terrified of Shepherd’s character. Two of his former employees broke down in tears during my interviews with them. At least three said they had gone for counseling, in no small part because of working for Shepherd. They asked for anonymity because they feared what might happen if they ran into Shepherd in town after this story. Other sources did not want to go on the record because they were concerned that Reichert, Kamlet, and their nexus of relationships in the legal community would make it difficult for them to keep their current jobs or prevent them from getting new ones in the small fishpond of the Denver legal community. This was why some of my sources who were not contacted by the OARC did not reach out to investigators. Gleason scoffed at the notion that witnesses and potential witnesses were reticent to speak because they feared such things. He said it was “baloney.”

One such source, who was not contacted by OARC, worked for Shepherd. “I don’t want my name mentioned,” the source said. “I don’t want my name linked. I fear retaliation. I did have him tell me to go into his calendar and find 30 hours. Next month, he said, ‘Wow, you did well, let’s find 60 hours.’ I would try to find as much valid time as possible. Then there were other times he had me put in as many as 90 hours per month that were not valid. Let’s say an associate had a time entry for work on a piece of a project; Willie would claim that he did that work, too, and I know he didn’t work on it. He was even out of the office. Not even in the country sometimes. I knew it wasn’t right. But this was the kind of man who would fire you if there wasn’t enough ice in his glass.” (According to two sources, Shepherd tried to fire members of the firm’s catering staff when there wasn’t enough ice in the pitcher on his desk.)

Another source, whom we’ll call Pat Smith, was a high-ranking employee at KSR for more than three years. Smith was so concerned about potential retaliation for speaking with me that the source not only insisted on anonymity, but also on concealing anything that would hint at the source’s gender. According to Smith, Smith not only had witnessed the sort of misconduct described in the Staks and Almon complaint—fraudulent billing and misuse of firm funds—Smith also had felt pressure to facilitate such misconduct. Smith facilitated the misconduct every month for years. All the while, Smith pleaded with senior management to do something about it, and when they did not, in Smith’s view, Smith left the firm. This source had specific, detailed information about Shepherd boosting his monthly “register” from 40 hours to 153 hours in a matter of minutes, with the PCLaw software, which kept track of all the attorneys’ billable hours. Shepherd, the source said, would “make it so.” Smith had information about specific misuse of firm funds, in which Shepherd would withdraw from the firm’s coffers as much as five-figure dollar amounts without so much as a piece of paper to note the “transaction.” After I began talking to Smith, Smith decided to contact the OARC this past February.

The first time Smith called the OARC with information on the Shepherd matter, the source says, an OARC staffer declined to acknowledge the investigation. The next day, an OARC attorney called Smith, according to the source, took some information, and said someone would be in touch. A little more than a week later, investigator Janet Layne called Smith. Smith told her all of what the source told me, and more, and, Smith says, Layne gave Smith the option of submitting a new complaint. Smith declined. Shortly thereafter, according to Smith, Layne informed the source the information was not germane to the investigation and/or was dated.

Smith was unwilling to file a complaint for the same reason the source is unwilling to be identified here: Smith feared retaliation. Further, Smith doesn’t believe that the OARC is truly interested in investigating and prosecuting unethical attorneys; that it doesn’t want to know the truth about the likes of Shepherd. When I informed Smith of the OARC’s decision in the Shepherd case, the source’s reaction was, “It’s a sham.”

Since Staks and Almon presented the partners of KSR with the memo, the new Kamlet Reichert has hemorrhaged attorneys. From a high of 48 lawyers, the firm has shrunk to less than half that size. Among the attorneys who have left are former equity partners Fred Winocur and Ray Gifford. Kamlet Reichert has moved into a much smaller office, and for months has been trying to merge with another firm.

Rebecca Almon and Lukas Staks remain at Ireland Stapleton, representing Ginn Resorts, along with a handful of clients they brought with them, and a few new ones. Their law office is not far from Willie Shepherd’s new law practice, Shepherd Law Group P.C. Occasionally, they pass by Shepherd on the 16th Street Mall. Back at KSR, they used to cower in his presence. Now they look him in the eye and keep going.

When I asked Gleason why his office turned away Pat Smith, he responded in an e-mail: “It didn’t happen that way at all. The allegations that [Smith] stated were much different in time and conduct and it was our decision that because of due process concerns we could not include them in the investigation underway.”

Referring to Shepherd, I asked Gleason who was advocating for the public; I said Shepherd was publicly censured, but he is still practicing law. “Yes. I 100 percent agree with you. People make mistakes. The discipline rules have various levels of mental intent. We discipline lawyers who engage in minor mistakes with private discipline. Lawyers like Mr. Shepherd who lie are disciplined publicly. And sometimes lawyers are more severely disciplined than Mr. Shepherd because their facts are more aggravated than Mr. Shepherd’s. That doesn’t make you or the public feel any better about it. I understand that.”

Maximillian Potter is executive editor of 5280. E-mail him at letters@5280.com.