The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

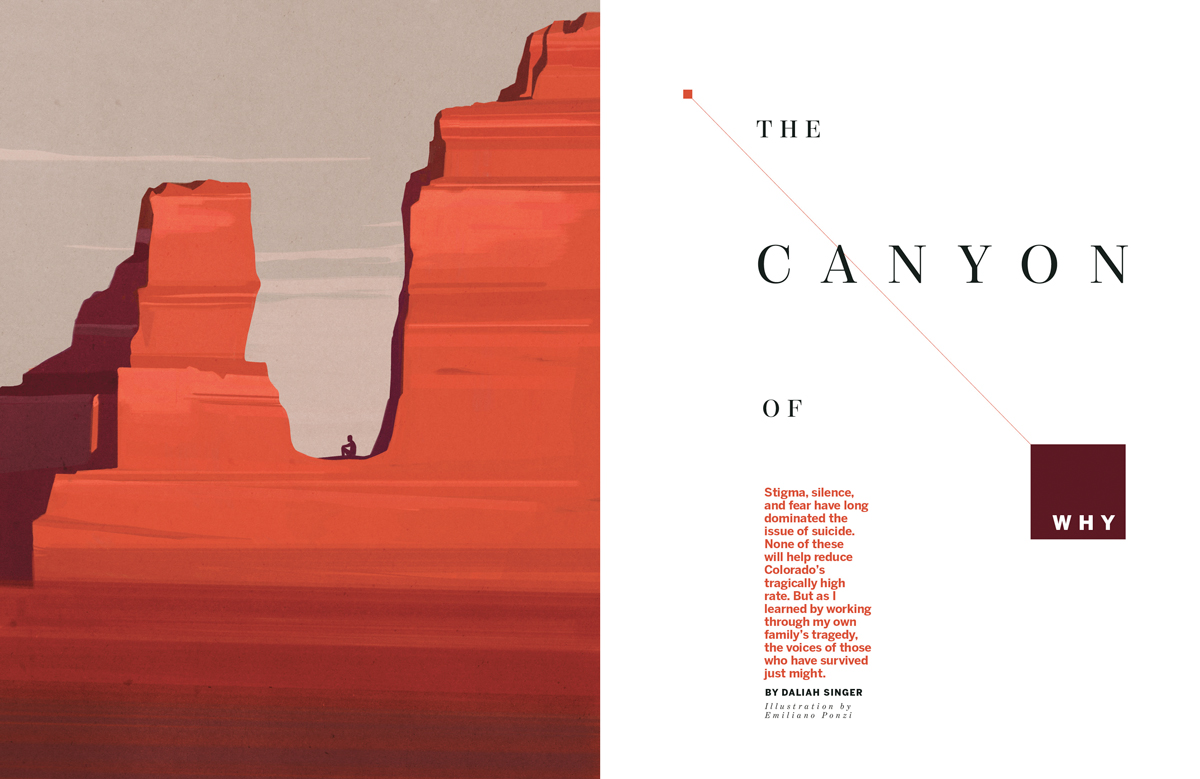

Why? is a common question after a suicide death: Why did he or she do it? Why didn’t I see the warning signs? Why would someone “choose” to die? Often, there is no direct answer. As we explore in “The Canyon of Why,” death by suicide is not caused by just one thing. Still, researchers continue to search for a clearer understanding of what causes people to believe death is the only solution to their pain. On World Suicide Prevention Day, we look at two recent theories are particularly intriguing, especially for Coloradans.

It’s In Your Genes

It’s long been known that people who have experienced the suicide death of someone close, particularly a parent, are more likely to die by suicide themselves. Developmental, environmental, and genetic factors are all thought to play a role. In July 2014, researchers at the John Hopkins University School of Medicine added some weight to the latter. They discovered significantly reduced amounts of SKA2, a gene involved in stress reactions, in the brains of those who died or attempted suicide. In addition, a methyl group that should not have been present was discovered attached to the gene; called DNA methylation, its presence suppresses the expression of the gene. Essentially, these actions stop the brain from ceasing its stress response, which, the researchers say, could turn typical reactions to commonplace stressors into suicide ideation. Across three sets of samples, the researchers could predict with 80 to 96 percent accuracy which participants were experiencing suicidal thoughts or had attempted suicide.

Researchers note that the 550-person sample size is small, but this study is the first to identify biomarkers of suicide with such accuracy. The hope is that this new information could be used to create a blood test to better recognize risk—which could be particularly beneficial to the population of pre- and post-deployment soldiers the John Hopkins crew is currently studying.

How High?

The Mountain West region is often referred to as the country’s “suicide belt” because its states consistently rank as the highest for suicide deaths, making up the majority of the top 10. Beyond location, they have one other major thing in common: high elevations. Perry Renshaw, a neuroscientist and professor of psychiatry at the University of Utah, thinks that fact might just be the key to lowering the area’s devastating statistics.

In 2011, Renshaw and a team of researchers analyzed state suicide rates based on various risk factors, including elevation, gun ownership, health insurance quality, availability of psychiatric care, poverty, and population density. Elevation was the second-strongest predictor of suicide deaths (after, intriguingly, the percentage of divorced white women in your county of residence).

The team started looking at how brain chemistry changes as the air gets thinner: serotonin levels, which help stabilize emotions, decrease, while dopamine—a neurotransmitter that helps control the brain’s reward and pleasure centers—rises. People with pre-existing mood disorders, such as anxiety and depression, may be more sensitive to these changes. (Those without such disorders typically feel happier living in the mountains thanks to a significant rise in dopamine production, according to Renshaw.)

Renshaw estimates that elevation increases the rate of depression in Utah by 20 to 25 percent—which would help explain the region’s consistently high suicide fatality rate. He cautions, though, that the elevation risk factor doesn’t exist alone; living in rural areas, access to guns, family history of depression, and other considerations can all still play roles in why someone takes his or her own life.

Other research has supported Renshaw’s theory. In 2010, doctors at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio published an analysis of suicide rates in 2,584 contiguous U.S. counties. Their findings: Suicide rates begin to increase between 2,000 and 3,000 feet in elevation. “It’s exactly the point at which your body starts to struggle a little bit to have enough oxygen to support all of its processes,” Renshaw says. Studies in South Korea and Austria have come to similar conclusions.

So what to do with this information? There’s no need to pack your bags for sea level. “We want to get to where we understand which treatments work and which don’t,” Renshaw says. “The practice of psychiatry may need to be altered slightly if, in fact, taking care of people living in Rocky Mountain states [is different].” He’s currently involved in a Salt Lake City–based clinical trial to study whether natural supplements such as creatine and 5-hydroxytryptophan can help balance out people’s brain chemistry at different elevations. And he’s working to pull more researchers into the fold: “We’re pretty far out on the branch,” he says. “These things take time when you’re trying to develop a new idea.” For now, awareness is key: If you have a mood disorder, know that you may feel its effects more keenly at elevation; contact your doctor or therapist if you notice changes.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call 1-844-493-TALK(8255), or visit coloradocrisisservices.org.