The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Passes in the alps, the Andes, the Himalayas—I’ve crossed many. I’ve crossed them in trucks and on trains and on foot. I’ve stood at the edge of the Great Rift Valley in Kenya where the road plummets down into ancient times. But my favorite vista is still the one you have on a clear day at the top of Kenosha Pass, 65 miles from downtown Denver.

The view, of course, is of South Park: a high basin, a grassland flat at around 10,000 feet that, seen from Kenosha’s summit, requires a few minutes for the ocular and spiritual adjustment necessary to take it all in. Above all, South Park, limned by the Mosquito and Taryall mountain ranges, is a staggering, thrilling volume of space.

The Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad made its way over the summit in 1879. Stagecoaches had been traversing it before then. Both were superior to the present-day highway and automobile, because both gave you more time to consider the wonder, the grandeur of the landscape. A word once applied to this kind of immensity was “sublime,” a sense of something fearful and terrifying, elevating and delightful, all at once. Something beyond beauty that pushes at your limits of explanation and understanding.

And it’s all right there, on westbound U.S. 285.

I first discovered South Park from a different direction. In the summer of 1973, my friend Ross McConnell and I were 15 and into bicycling. We decided to ride a loop, from Denver to Colorado Springs via Franktown, west into South Park to Fairplay, and then northeast across South Park to Kenosha Pass and down U.S. 285 back into Denver. Two parts of this I recall as particularly awful: sleeping on the dirt in an RV park in Colorado Springs, my sleeping bag inside an orange plastic tube Ross had offered me for rain protection. And then riding across South Park.

The place itself, of course, was stunning. Once we’d climbed out of Woodland Park and up Ute Pass to about 9,000 feet, the world opened up and spread out in the most magnificent way. And it just kept going and going—the farther we went, the bigger it seemed to grow.

The problem was the wind. All that empty space was occupied by a ferocious energy, aimed at our faces. Though we rode on mostly level ground, we had to downshift to the low gears we used for climbing. More than once, gusts of wind pushed us nearly to a standstill, but we ground on. I was fairly new to distance cycling and had recently upgraded my Schwinn Continental to a Peugeot PX-10, which I rode with sneakers and toe clips. Ross, on a French bike called a Follis with cycling shoes and cleats, showed me the utility of drafting—riding close behind him, using him as a windbreak—and then invited me to take turns in front so he could rest. It helped, but still we managed little faster than a crawl. The vast scale made it feel as though we weren’t progressing at all, as though the physical world had set itself against us.

What a sense of relief I remember as finally we approached the bottom of Kenosha Pass. Yes, we still had to climb, but the wind would be out of our faces. It would be so much easier. And in the half hour or so it took to summit, my mood did a 180-degree turn: That view to my right, across the terrible windy plain, was one of the most gorgeous things I had ever seen.

It wasn’t until a year or two later that I returned to South Park, in the wintertime. My friend Jay Leibold and I had gotten our driver’s licenses, and his family had a little A-frame in the woods near Fairplay. I’d been skiing since I was six or seven, mainly with the Eskimo Club at Winter Park (to which I’d travel on the ski train from old Union Station, dark and all but abandoned at 6:30 a.m. on Saturday mornings in the 1970s) and at areas like Loveland or Keystone before I-70 became a “corridor.” Jay was a downhill skier, too, but in Fairplay he did cross-country, which I’d never tried. We wouldn’t go to any “area,” Jay explained. We would drive up a road near his cabin, and where it stopped being plowed, we would park, put on our skis, and go.

The road took us to the foot of Pennsylvania Mountain, 13,006 feet and unprepossessing. There were trees below the bald summit, but it was freezing and gusty—we drove his family’s Wagoneer through some drifts to get to the end of the putatively plowed road. Outside the car, the wind caught the skis in my hands and swung them horizontal. Maybe, I thought, we should get back into the car and rethink this, but Jay acted as if the weather were normal. I’d warm up once we got going, he claimed.

We got going. There was a lot of fresh snow, which meant we had to break a trail in deep powder. But that wasn’t all: In many places, there was crust underneath the fresh snow. Sometimes we would drop through that layer when we took a step with our skinny skis, and sometimes we would not. Our progress wasn’t graceful, but within an hour or so we had climbed above treeline. En route we passed a snowed-in road, with a crude “KEEP OUT” sign and a chain across it, that led to a still-active mining claim worked in the summer by a couple of guys, Jay explained. We tried skiing down through the glades—Jay was just starting to get good at telemark turns on his wooden Bonna skis. But progress was regularly upset by the crust, which would keep us on top of the snow only to drop us down into it without notice, often resulting in a fall. We sat on a log to eat lunch, brushed ourselves off, and noticed the midday sky turning surprisingly dark; snow began to fall hard, blasting my cheeks.

Jay had proposed returning to the cabin via a different route. By heading toward the Mosquito Pass road, he said, we could do a loop. That road connected with the road the A-frame was on. It sounded reasonable, especially since, as he said, it would help us avoid “the cliffs” on the side of Pennsylvania Mountain.

We stuck to this plan. But as we slogged on, we could see less and less. The only way visibility could have been worse is if the sun had set—which soon enough it had. I was worried but didn’t see any point in complaining, since I knew Jay had the same stake in achieving a round trip that I did. Also, as our guide, he was breaking the trail and doing most of the work. (Years later, he confessed it was his first time exploring apart from his family, and he was borderline panicked.)

Returning to the cabin was like coming into a ski lodge after a long day on the mountain, only better. For here there were no crowds, no overpriced drinks, no steam-bath-like end-of-day humidity. Only warmth, from the propane floor heater, and quiet and cold beer.

We shed our ice-encrusted outer layers and warmed up at about the same speed as the frozen pizza we placed in the oven. Enhancing that pizza with veggies, sausage, and extra cheese would become one of our cabin rituals. The harsher the elements, I realized, the sweeter the shelter, and in South Park that insubstantial A-frame began to seem sweet indeed.

That weekend’s trek was the first in what became a series of epic adventures. Other Denver friends would come up, too, in their borrowed family cars. We’d freeze, then melt. We’d bake pot brownies and listen to Frank Zappa on the cheap stereo. And, when cabin fever struck, we’d head into town. At the time, Fairplay had a small grocery, the Family Store, where you could get basics. It had a good bar at the historic Fairplay Hotel. Instead of the condos of Summit County, it had old miner’s cabins, crooked wooden sheds, and slapdash houses of which no two were alike. It had several churches, including a charming tiny Catholic one where, Jay informed me, his parents would bring him and his brother and two sisters to Mass when the family was in residence at the A-frame. It had an entire historic district, South Park City, of old buildings, most of them relocated from various parts of South Park into a tourist attraction on the western edge of town; you could imagine scenes from Westworld set there.

And the town had a small concrete-and-stone monument to a burro named Prunes. Taking our picture in front of the monument became an annual tradition, as did chanting the words inscribed on it: Prunes, a Burro. Fairplay, Alma, All Mines in this District. (Repeat it several times to discover the meter.) We often spoke of coming back in July for Burro Days, with its footrace in which runners accompanied by gear-laden burros had to make their ways from Fairplay up Mosquito Pass and back.

Anyway, while a lot of other parts of Colorado were getting built up and crowded, Fairplay mostly wasn’t. Its wind and cold were a developer’s nightmare, and succor to our souls. The A-frame became a favorite place for Jay and me, sometimes our respective girlfriends, and other friends to spend New Year’s Eve. We gathered there more often than not for some 20 years. At college in Massachusetts, I subscribed to the weekly Park County Republican and Fairplay Flume to keep abreast of local news, such as a proposed Olympic bobsled facility (never happened) and a regional airport (ditto). After college, with Jay out of town, I repaired more than once to the historic Fairplay Hotel alone with my laptop to work on my books Rolling Nowhere: Riding the Rails with America’s Hoboes and Coyotes: A Journey Across Borders with America’s Illegal Migrants. With Jay in town, we hosted my friend Roberto, who lived in Washington, D.C., on a tour of the mountains. He was familiar with ski towns but had never seen a place like Fairplay. One day, as he and I left the Family Store, we came upon an argument between two whiskery guys at the back of an old pickup truck. They were shouting and throwing things and one yelled at the other, “Why you lyin’ sack o’ shit!”

Roberto was thrilled. For a tenderfoot like him, it was the perfect Western moment, and during the rest of his visit he did not miss the opportunity to call me a lyin’ sack o’ shit. Even now, years later, after a drink or two, he will delight in reminding me that I am a lyin’ sack o’ shit.

Then change: I got married. Not long after, my wife and I had kids. Taking off for a few days in the cabin with Jay became difficult to justify when it meant leaving Margot alone at home with the toddlers. Jay, by then living in San Francisco, married as well, but that didn’t make as big a difference as my having children did. Margot and I brought them to the cabin once in the summer when they were small, and Jay joined us for the shortest hike from the cabin ever: We found a little spot by a creek, ate a snack, threw some rocks…and then the wind kicked up. Time to head home.

We weren’t the only ones getting older. Ten years ago, Jay’s father, in his 70s, decided it was time to sell. Were Margot and I interested in buying? Agonizing ensued. We made another summer visit to decide the question—summer seemed the season with the best chance of convincing the kids, now in their early teens and with experience downhill skiing at Winter Park and Aspen. It was a nice day, but as we got out of the car we attracted a lot of mosquitoes. I brought the tour indoors, showing them the cool loft upstairs, the slanting walls, and the view through the sliding glass doors of a rounded, snow-capped, windswept peak framed by pines.

“That big mountain is called Silverheels,” I explained. “They say it’s named after a dance hall girl who took care of the South Park miners during a smallpox epidemic more than a hundred years ago, until she mysteriously left town.” We stepped outside, and this time we were really swarmed by mosquitoes—the kind that make you long for some good gusty wind. My family pronounced the verdict, carefully, knowing it would be difficult for me to hear. The verdict was: “Meh.”

That would be it. The house was sold.

Jay and I stayed close. We’d see each other on both coasts and regularly in Denver at Christmastime. We’d visit family and then try to wrangle a few days in the mountains—downhill skiing if the snow was fresh but otherwise cross-country skiing and snowshoeing. Once when the gang was gathered and we were waxing nostalgic about the good old days in South Park, Margot quipped that it sounded like “Brokeback Mountain for straight guys.” Which wasn’t far off the mark, actually.

Then this past fall, the stars aligned: Jay and I would be in Colorado for the same few days in October. We saw a chance to head up to South Park again and see what had changed. In Colorado, of course, revisiting old haunts can be like inviting your heart to break; nothing stays the same, and there are always more cars and houses. We thought the odds might be with us in South Park, though: Due to its long history of placer mining, it never looked pristine to begin with. And it didn’t seem the population had grown much. We’d head back for a three-night, four-day look-see.

On our drive up Turkey Creek Canyon from Denver, we stopped in Tiny Town—Ross and I had overnighted more than once amidst its ruins during those bike tours in the early 1970s, unrolling our sleeping bags in the tall grass between miniature manors. Now its little shops and houses have been restored and expanded, and only a very tiny person could slip in through the new fence and sleep there.

Jay and I were not so tiny. Girth-wise, in fact, we were somewhat larger than we had ever been. So perhaps we should not have searched out our next historic landmark: Coney Island Boardwalk hot dog stand, the restaurant in the shape of a giant wiener in a bun that had been our regular stop near Conifer. But when we pulled off the highway there, across from the sledding hill, we discovered the wiener gone. Jay remembered that it perhaps had not been demolished, only relocated, and half an hour later we tracked it down in the woods in Bailey, the stucco relish and mustard on its roof intact. Delicious!

We had rented an old cabin in Fairplay on Airbnb. It was not an A-frame in the pines, but it breathed history: Some of its walls were log, some had vinyl siding. It had been expanded at least three times but was still small, slant-floored, and cozy. Outside the front door, a pair of crossed skis with cable bindings hung on the wall; giant antlers were mounted above the doors to a shed.

Our agenda was simple. We wanted to revisit old haunts and a couple of new ones, as well. We wanted to talk to a few people who knew what had been going on in South Park lately. We wanted to eat and drink. And, before we were done, we wanted to see if we could still climb Pennsylvania Mountain.

On our first full day, we ate lunch in Alma with Linda Balough, a retired Park County official who seems to know everybody. Linda drove down from her home up Hoosier Pass to meet us. Outside it was breezy. Within minutes, of course, we were talking about the wind. Boreas Pass, a dirt road that follows the old railroad route from Como to Breckenridge, was named for the Greek god of the cold north wind, the bringer of winter. Kenosha Pass is often closed due to blizzards, and the wind meter there, which stops measuring after 109 miles per hour, often maxes out. Hoosier Pass, though, the route to Breckenridge and Summit County, is closed much less often. “We used to joke,” Linda said, “that they had to keep CO 9 open because it was the service entrance.”

Linda cited the wind as one factor behind the area’s stubborn resistance to development; in all the years of mining and ranching and cockamamy schemes, as she told it, “nobody ever got rich in Park County.” Had the show South Park on Comedy Central—which celebrates its 20th anniversary this month—brought tourists, at least? Our waitress said some customers were attracted by the name of the restaurant, the South Park Saloon. She had served French visitors and Germans, and that afternoon, Californians perched in a booth next to ours. A clothing store in Fairplay tries a little harder: It has placed a painted plywood sign with pictures of the show’s main characters in its front yard; kids can put their heads through holes where the faces should be. Fairplay, population 679, resembles the town in South Park more than any other in the basin.

Where once there were streambeds, long, high piles of alluvial rubble—the products of placer mining for gold—snake around the edges of Fairplay, and in many other parts of South Park. The machines that produced these pebbly mounds, called dredges, are long gone—except for one, Linda said, which she had tried (and failed) to turn into a tourist attraction. “Do you know the one?”

Our mission to locate and explore the big dredge took on the feeling of our teenage missions to sneak into clubs like Lakewood’s After the Gold Rush when we were 17, or swim clubs like the Crestmoor Community Association where we weren’t members. Linda’s directions were good, and about half an hour after lunch, we located the dredge. It sat marooned in a sea of dirt and rocks on a hillside south of Alma, looking like a punk ocean liner run aground. A gangplank stretched between the machine and the hillside. We looked around: A few trucks were parked within view, and we were visible to some houses up the hill. But the thrill of trespassing overwhelmed the caution of middle age. Soon we were across and traversing the four floors of this industrial dinosaur—urban exploration at 10,000 feet.

The next day, we drove. We visited Como, with its ruined stone railroad roundhouse. I’d once come close to buying an old miner’s cabin there. That cabin has since been painted pink and abandoned; saplings fill its yard and spring out of open window frames. We checked out the Como Hotel, where I had stayed and eaten when examining the miner’s cabin. We remembered a cross-county ski route up Boreas Pass, just above Como; the gentle railroad grade makes for a civilized ski.

Then we drove to Hartsel, the town nearest to some truly vast open spaces. We stopped at the Rocky Mountain Land Library—a former ranch now owned by the City of Aurora, which recently gave a 90-plus-year lease to two idealistic book enthusiasts who aim to transform it into a library and education center. Ann Martin and Jeff Lee, the founders, showed us around ruined buildings which they hope to convert into artists’ studios and residences. (They recently raised more than $100,000 through a Kickstarter campaign.) Their plan is certainly no more far-fetched than that of real estate speculators who, in the 1960s, attempted to promote a subdivision of 10,000 five-acre ranch tracts near Hartsel “without notable success,” in the words of Virginia McConnell Simmons in Bayou Salado: The Story of South Park. Only a smattering sold, but the aftermath remains: an outsize, improbable grid of dirt roads superimposed over an immense basin. You can see most of the roads—given Native American names such as Shawnee Trail, Comanche Road, and Wigwam Trail—on Google Earth, just south of Hartsel. But you need to be on the ground to appreciate just how odd it is, a bunch of dirt roads cut into the prairie that lead to practically no houses at all. Yes, there are a few, often trailers with a dog and assorted stuff outside and a perimeter of barbed-wire fence. If you’ve seen photos of the home of Robert Lewis Dear Jr., the terrorist who murdered two civilians and a policeman at the Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs in 2015, you’ll know what some of these look like, because this is where Dear lived.

Jay and I drove these roads in the golden light of late afternoon. It was empty out there; some of them had a feeling of not being driven on for weeks. Though the view was mostly wide open, there were some rises and dips; as we came down one hillside, we saw the road would lead us into the path of about 75 bison that were trotting downhill toward an open gate. No wrangler could be seen herding them on their way, no pickup truck. We parked, pausing our travels through space and imagined they were taking us back in time.

Returning to Fairplay that evening reminded me of swimming across a giant lake. There were a few islands—hills, ridges—out there, but mostly you felt unmoored, suspended in a different medium than everything surrounding South Park.

That night we dined at an Italian place, Millonzi’s Restaurant, on Front Street with a friend and colleague of Jay’s sister. Josh Voorhis, a district ranger for the U.S. Forest Service in South Park, had recently moved to the area from Wyoming, by way of the Western Slope, with his wife and kids. We talked about how lodgepole pines in South Park had mostly avoided the pine beetle so far (prevailing winds when they breed are south to north) but how spruce beetles still might be coming—lately, there are nearly 20 more frost-free days annually in the Southwest region of the United States than there were several decades ago. We talked about how the region had recently been dangerous for law enforcement; four of 20-some deputies in the county had been shot in 2016. Part of Josh’s job was to enforce restrictions on off-road vehicles on forest land, but that was difficult given the size of his staff compared to the size of the region. We talked about how the nearest pharmacy and clinic were over Hoosier Pass in Breckenridge. And of course, we talked about the wind.

“I thought Wyoming was windy,” Josh said. “But compared to here, Wyoming isn’t windy.” He spoke of waking up one morning to the wind shaking his house. “I really thought my roof would come off.” The wind, again—plaguing, and saving, South Park.

Sunday was our last full day. Our goal was to summit Pennsylvania Mountain, which we had climbed often but not in nearly 20 years. The looming question: Could we?

We drove by the old A-frame first. It had a For Sale sign in front. Nobody was around, so we got out to have a look.

There was a nice new deck. We stood on it and peered inside through the sliding glass doors: Old carpet had been replaced by shiny wood floors. The big propane floor heater—and the even larger propane tank outside—were gone, as was the cheap fireplace. Our beacon in a blizzard was now a fair-weather house.

Jay and I walked by the little homemade miniature golf course he and his siblings had built nearly 50 years earlier on the pine-needly ground, the “greens” still outlined in stones. Jay asked, “What would an archaeologist think?” There was the tetherball pole and one of the stakes for the horseshoe pit. I remembered the time I got annoyed by our friend Scott, took his squirt rifle, broke it in half, and hurled it out the sliding doors into the woods. There was no sign of it now.

Jay was sad. It was time to get out of there—time to hike.

We used a different trailhead, one that allowed us to start a little bit higher up than the one we took when we’d ski. Though it was midmorning, we were the first ones there. As Josh had noted, the trailheads for Colorado’s fourteeners are typically thronged, but the thirteeners are pretty empty.

And here, as we started uphill, I was reminded of my friend, who was sort of like the brother I never had. We saw each other only a handful of days a year now, but in some ways, I knew Jay so well: how he always assesses the clearness of the sky in the morning. How he’s fascinated by topography, always aspires to get to the top of the unknown road for its vantage. How he loves maps, can name all those peaks. From the small town of Jefferson, he had spied the “backside of Mt. Evans.” En route to Hartsel, he had named Mt. Elbert. After all these years I suppose I should have known these mountains—certainly Jay acted as though I should—but I didn’t. He took care of that for both of us.

You would not say that our progress was swift. Various hiking parties passed us—mostly younger people, but some more senior. We found a shallow miner’s pit to sit in and eat sandwiches we’d bought at a coffeeshop in Fairplay. Then we got back to it, spreading apart as we moved toward the summit at our own speeds.

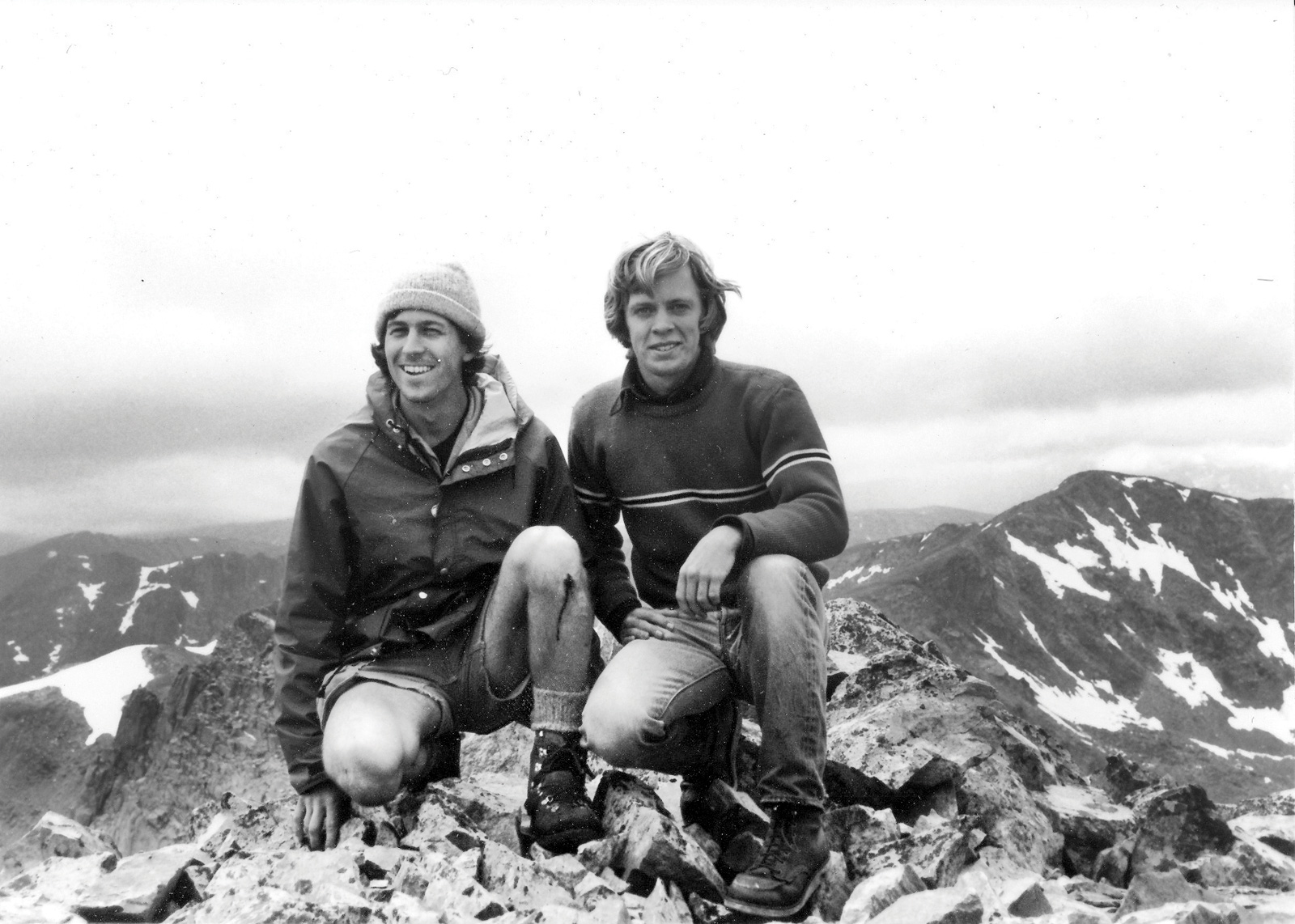

By the time Jay reached the top, I was cooling off and it was beginning to snow. The wind was gusty, as usual; the clouds were dramatic, and the peaks around us went into and out of the sunlight. “There’s Mt. Sherman,” Jay said, half to himself. “And Mt. Lincoln and Mt. Democrat.” He changed his shirt, remaining bare-chested—in snow flurries—for five minutes or so. We remembered the time we had spotted a herd of bighorn sheep up here. We looked into a nearby valley and saw a party of hunters hiking in DayGlo colors hundreds of feet below. Jay said he liked the feeling of his boots upon tundra, the spongy little plants. We took pictures.

“Ready to go down?” I asked, chilled. He was not. Had I really forgotten how challenging it was to pry Jay off a mountaintop? Scott, a perennial climbing partner of ours, would have laughed and reminded me it was a fixed feature of his character.

“Jay, I’m getting cold.”

“You can start down, Ted. I’ll catch up.”

So I did, and shook most of my chill in the process. Still, when you have been out in nature, South Park–style, one’s car parked at the trailhead can look like an oasis. I dropped my pack in the back seat, swapped my boots for sneakers, eased into the front, and slammed shut the door. Beautiful silence—no wind. A sliver of South Park was visible above the straight dirt road ahead. Jay was en route and the ritual nearly complete: the same mountain climbed, only different.

Ted Conover is a writer who teaches journalism at New York University. His book Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2000.