The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

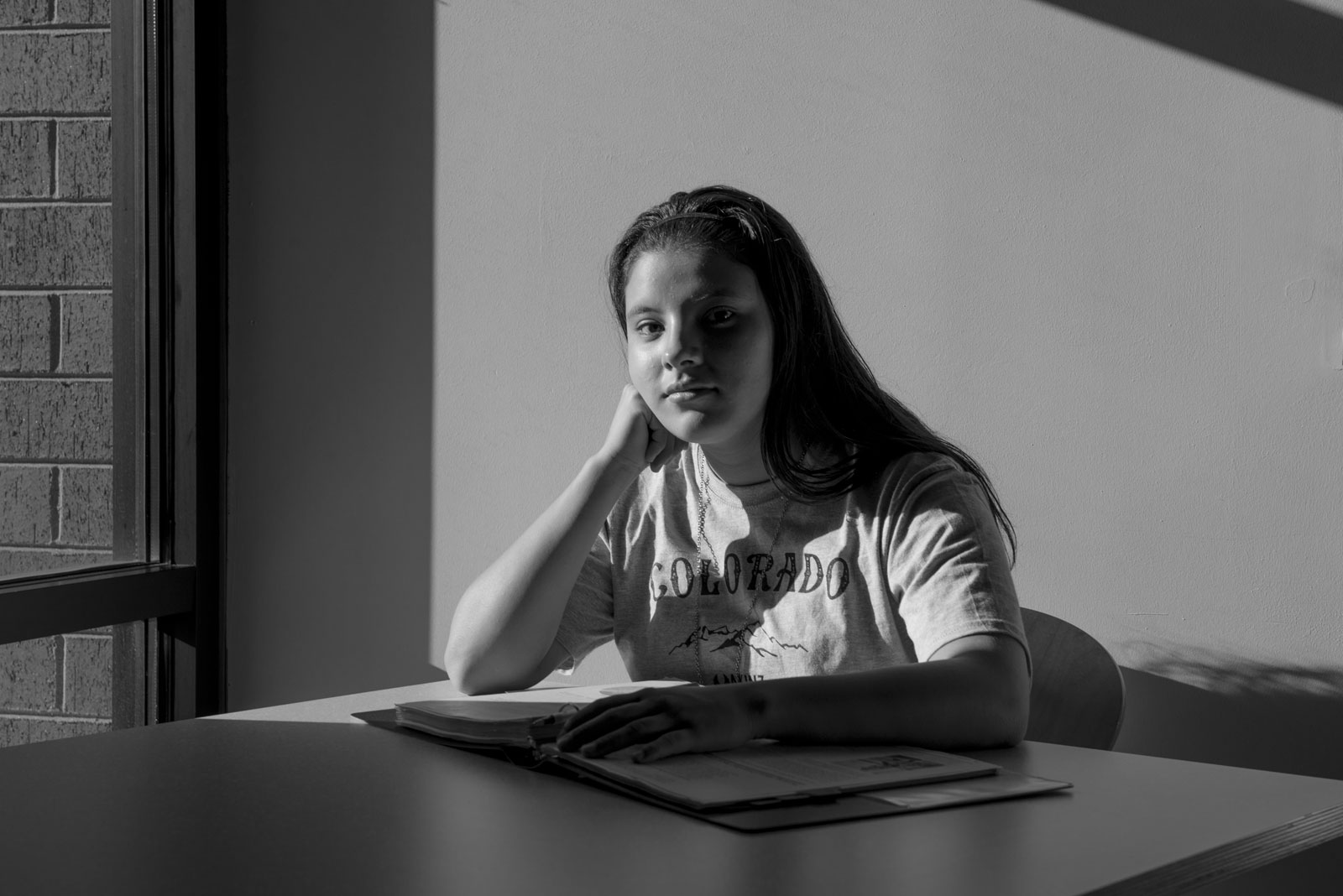

The dozen students in a basement classroom at North High School are antsy at 8 on an April morning. The school year is nearly done, and the call of summer vacation is palpable. Despite her peers’ fidgeting, 18-year-old Rachel Hernandez reads intently. She’s equally impatient but can’t lose focus now. Some of the college scholarships she’s earned—more than $30,000—are dependent on her final grades. She needs the money because there’s no financial help for her otherwise.

Hernandez’s day started three hours, four bus routes, and 20 miles ago. More than 3,100 Denver Public Schools (DPS) students have similar stories of trying to stay in school when they do not have permanent homes to return to at night. Hernandez grew up in public housing just east of Sunnyside, and she’s never lived with her mother, who has been on and off the streets with an alcohol problem. Her father wasn’t in her life. Her maternal grandmother took Hernandez and her three older siblings in for a few years. When she died in 2005, the kids moved in with Hernandez’s aunt—who has two kids of her own. Hernandez and her sister Ruby did the grocery shopping, the house cleaning, and most other chores. During that time, Hernandez says she was sexually abused by someone close to her. She ran away twice.

Hernandez, stubborn and strong-willed, became determined to make changes for a more secure future. Since her junior year she has lived with her great-aunt in a relatively stable home with her own room but far from her school. (Although Hernandez doesn’t live in the neighborhood where North is located, DPS works with students like her to keep them in the same schools throughout their educations, instead of transferring them.) She’s happy and comfortable there, but the distance means sleep is rare. On top of the lengthy bus rides, Hernandez’s spring schedule included two jobs to help pay rent, a one-day-a-week internship with a Latino environmental group, therapy, and mentorship programs. The sleepless days paid off: She’s a 2015 Mayor’s Youth Award recipient and was accepted to all four Colorado colleges she applied to. She’ll be just the second person in her family to attend college. “I want to be different from them,” she says. “I want to be remembered for something. I want to live big.”

On this April day, like many others, Hernandez skips lunch, opting to work on college paperwork in between classes. Later, she chats with her two mentors. Both are pushing Colorado State University, though Hernandez is suddenly leaning toward Metropolitan State University of Denver. It’s closer to home, less expensive, and, she argues, has a highly ranked criminal justice program (she wants to be a probation officer). She’s visibly frustrated. She says over and over that she doesn’t want to take out loans. She’s already made it this far on her own. “What if I don’t like CSU? What if I’m homesick?” she asks, her concerns slipping through in a rare moment of vulnerability. “Then give up and quit,” one mentor retorts. Hernandez stares at him, a play-by-play running through her mind of every time her family insisted she would never achieve anything. Her voice is clear when she responds: “Why would I do that?”