The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Every summer, 5280’s deputy art director, Sean Parsons, marches into his backyard armed with a baseball bat. He’s not practicing his swing—but instead protecting his grape vines, which become swarmed with Japanese beetles. In wrath and irritation, Parsons swings away at the vines, knocking the bugs into a bucket of soapy water.

The method is unconventional, but according to Parsons, it makes the “best threat” for the hungry insects. Across the Denver metro area, thousands of other homeowners are trying similar tactics (like owning chickens or employing a cordless vacuum) to get rid of the invasive pests.

The little green beetles have a pretty iridescent sheen, but they can devour more than 300 species of plants, skeletonizing the leaves and destroying entire backyard gardens in the process. Native to Japan, Popillia japonica was first discovered in New Jersey in 1916 and steadily marched westward across North America.

It made its way to Colorado in the early 1990s aboard nursery stock, and has since become a reliable summer scourge in the Denver area. Each June, the adult beetles emerge from underground (where they hatch and grow in their larvae form.) By late summer, the females lay their eggs in wet turf, starting the process over again.

“When the beetles first got to Colorado in the 1990s, not much was done to eradicate them,” says Wondirad Gebru, plant industry division director for the Colorado Department of Agriculture. “That’s because Colorado’s dry climate can’t sustain the beetle grubs. They can’t live in the natural environment.” But in Denver and its environs, where homeowners water their lawns, parks are well manicured, and golf courses are lush, the grubs were able to thrive. Today, Japanese beetle populations are high in the metro area, and most experts agree that it’s too late to get them out of the city.

But the beetles aren’t as common everywhere else. In 2002, the bugs were spotted for the first time in Palisade, more than 200 miles southwest of the Mile High City. They quickly posed a threat to the town’s vibrant peach-growing industry. Local leaders were able to spread pesticides on nearly every single lawn in the town, killing the beetles in their grub stage. The city, in collaboration with Colorado State University, tracked its progress by counting the number of traps (which emit a scent that attracts the critters) filled with dead beetles. By 2009, not a single beetle was caught in Palisade’s traps—signaling that the eradication efforts had worked.

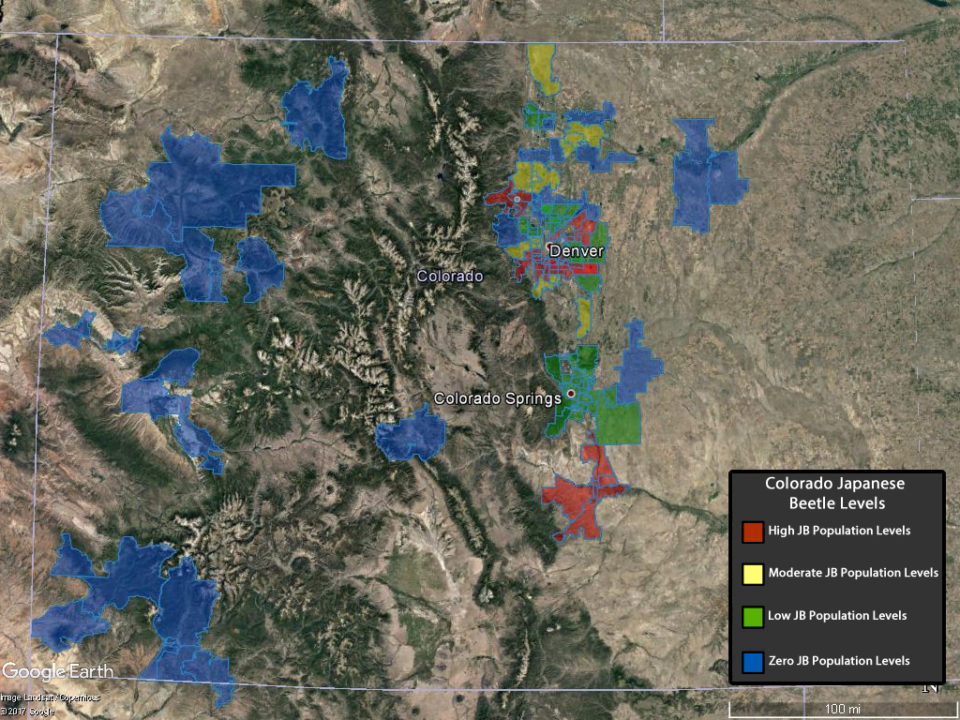

That same year, the state imposed an external quarantine, meaning that nursery plants could only be imported to Colorado if the flowers, shrubs, and other potential beetle vectors were first treated with certain insecticides, or if inspectors could certify they were beetle-free. In 2016, the quarantine was expanded internally to include 11 counties along the Front Range that are now considered infested. Nurseries and landscapers around Denver and Boulder must now make sure their stock is beetle-free before transporting plants elsewhere in Colorado.

The beetles have won some battles along the way. In 2022, they were once again found elsewhere in Mesa County, despite the state’s extensive quarantine efforts. “We will never really know how they got here,” says Melissa Schreiner, an entomologist with Colorado State University Extension who works in Mesa, Delta, East Montrose, and Ouray counties. “They could always land on your clothes before you get in the car and drive to the Western Slope. But we saw such a sudden increase in their numbers that it’s likely they came as grubs on turf grass for new building developments.”

Since then, CSU Extension has partnered with Mesa County’s Noxious Weed and Pest Management office, the City of Grand Junction, and the Colorado Department of Agriculture (CDA) to try to beat back the bugs. With the help of a $110,000 grant from the CDA, the organizations treated more than 1,400 acres of turf last year. “We’re also taking root and soil samples to check the efficacy of the insecticide,” Gebru says. “We’re really focused on protecting the Western Slope.”

And the efforts seem to be working: Scientists captured 86 percent fewer beetles in Mesa County in 2024 than in 2023. “You can’t stop biology, so I can’t say for certain that the beetles will be eradicated this time,” Schreiner says, “but I’m hopeful. We meet at the end of every year to look at the data from the traps. It will be a discussion between all agencies to determine if the efforts continue.”

If you live in what Mesa County deems an “infested area” (find the map online), Schreiner encourages homeowners to opt into government-funded lawn treatment to kill the grubs. Homeowners in the county outside of the infested area who find suspicious beetles or grubs should contact the CSU Tri-River Extension office.

Denverites, we’re on our own for this one. The beetles are so pervasive in the metro area that CSU doesn’t offer lawn treatment to get rid of them, which is why we asked Lisa Mason, a horticulture specialist for CSU Extension in Arapahoe County, for her best tips to banish the beetles.

Read More: Where Are All of the Miller Moths?

How to Get Rid of Japanese Beetles

1. Don’t use traps.

“Traps are only good for determining the presence of the beetle, but not for control,” Mason says. That’s because the traps use a strong scent to attract the beetles, which can actually bring more to your yard. If your neighbors insist on using traps, Mason recommends making sure they’re at least 30 feet away from your favorite plants.

2. Be wary of pesticides (and if you do use one, be selective).

Pesticides that are marketed to kill adult Japanese beetles can harm beneficial pollinators, like bees. Plus, Japanese beetles like to eat vegetables—and spraying insecticides on vegetables can make them inedible. Mason says the best pesticide on the market contains the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, of the variety galleriae, which is safe to spray on edible plants and won’t harm pollinators. “You do have to regularly reapply it every few days because it can degrade in the sun and wash off when it rains,” she says. Find it in brands like BeetleGone! and BeetleJus!

3. Pick them off plants.

If you find beetles on your plants, Mason recommends removing them by hand (the baseball bat method is a little unconventional, but hey, whatever works.) Though tedious, removing each individual bug does make a difference: “When one beetle starts eating a plant, the plant releases this chemical scent that attracts more beetles,” she says. “Even though it’s a chore, it’ll help reduce that aggregation feeding.” While you can squash the beetles, Mason says it’s easier to drop them in buckets of soapy water.

4. Choose beetle-resistant plants.

Although Japanese beetles are happy to munch on more than 300 species of plants, Mason says that there is still plenty of greenery that the beetles seem to avoid, like Columbine flowers, lavender, mint, and oregano. Find a full list of plants that beetles don’t find tasty on CSU Extension’s website.

5. Remove grubs before they turn into beetles.

According to Mason, one of the best ways to control Japanese beetle populations is to keep them out of the yard before they turn into adults. She recommends gently tugging on the grass in your lawn each spring to check for grubs. “If it’s firmly rooted, there’s likely no grubs in there,” she says. “But if you can peel up the sod, you’ve probably got Japanese beetle grubs.” Since the larvae need moist soil to survive, Mason says to let your soil dry out between waterings which can kill the grubs before they emerge in the spring.

For questions about Japanese beetles where you live, contact your local CSU Extension office. Find the full list of CSU Extension offices online.