The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

There’s a major change coming in how we heat our homes, power our toasters, cook our scrambled eggs, and drive from place to place. In fact, the transformation is already in its nascent stages in Colorado and the rest of the country. It will have a profound impact on the planet we call home, but in day-to-day life, we’ll hardly notice a difference—except to appreciate cheaper bills and zippier acceleration in our cars.

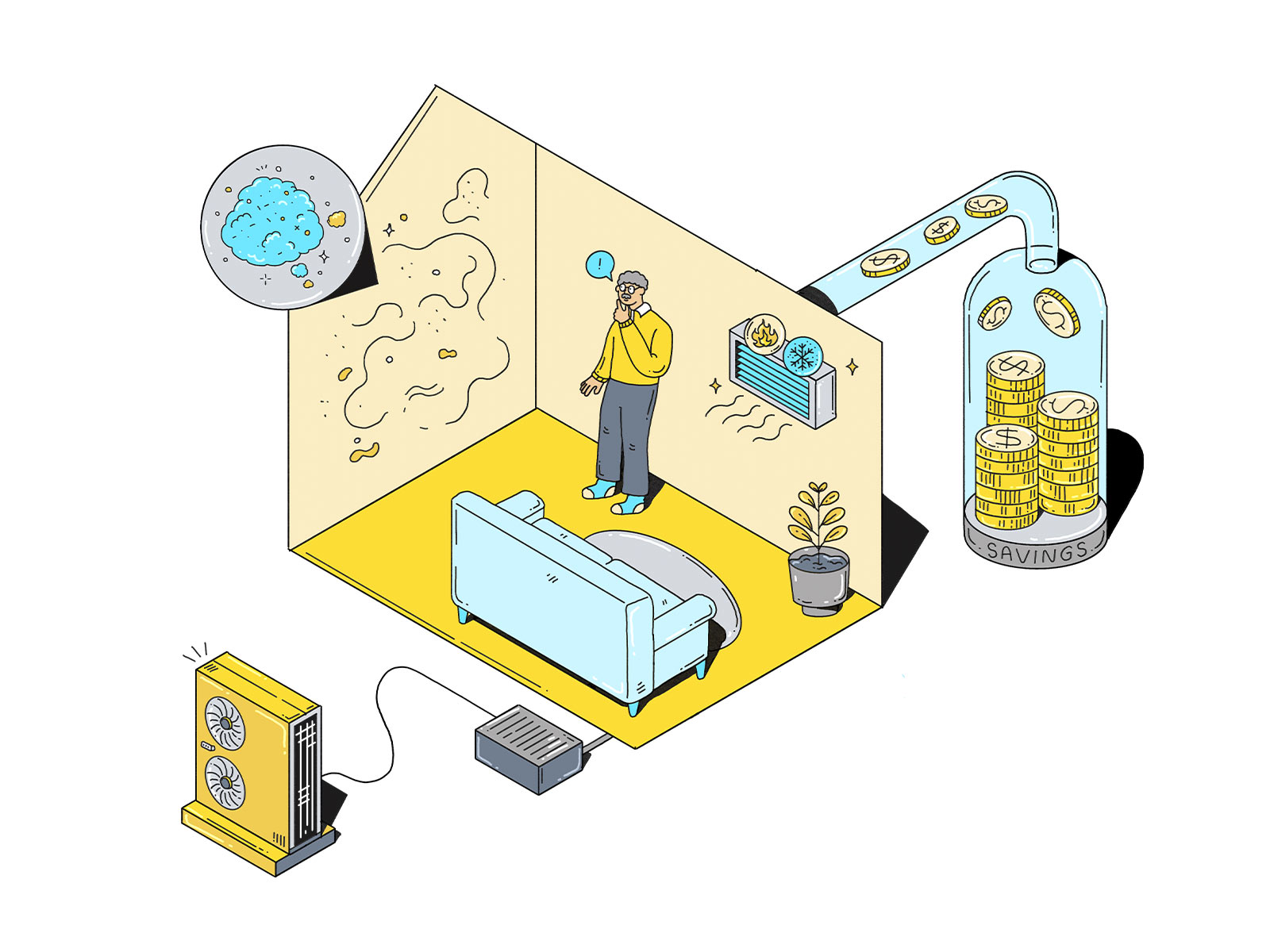

The changeover we’re talking about is beneficial electrification, or “moving from traditionally fossil-fuel-powered devices to their electric counterparts,” says Kyri Baker, a University of Colorado Boulder professor and fellow at CU’s Renewable and Sustainable Energy Institute, a research and education organization partnered with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. That means weaning ourselves off internal combustion vehicle engines and gas furnaces, boilers, water heaters, fireplaces, dryers, and stoves in favor of fully electric vehicles (EVs), air-source heat pumps, water heaters, and cooktops—and the more clean energy we generate from solar panels to run them, the better. “Electrification is really the biggest thing we can do to drive down emissions as quickly as we need to in order to avoid the worst of the climate catastrophe,” says Gina McCrackin, climate action collaborative manager for the Walking Mountains Science Center in Avon, an environmental education and sustainability nonprofit. “It’s a massive deal.”

That’s not to say electric devices aren’t responsible for any carbon emissions: A decent chunk of the electrons on Colorado’s grid right now come from burning fossil fuels such as natural gas and coal on the utility level, so electricity itself still has a footprint. But the juice coming out of your outlets is greener than you might think, and it’s getting more eco-friendly every year. In fact, Colorado and the state’s major electric utilities have committed to dramatically reducing the use of fossil fuels in favor of solar, wind, hydropower, and battery storage. By 2030, Xcel Energy plans to be using 80 percent renewable energy, and Holy Cross Energy, a smaller utility on the Western Slope, has pledged to produce 100 percent clean energy by the same year. This kind of rapid drawdown on climate-warming fossil fuels is exactly what experts say is necessary to mitigate the climate crisis.

But in order to make beneficial electrification, well, beneficial, we must begin to swap out our fossil-fuel guzzlers now. Fortunately, the conversion doesn’t have to be prohibitively expensive or difficult. The biggest-ticket consumer items—electric vehicles, solar panels, and heat pumps—generally do involve a significant upfront investment, but they pay off in lower energy bills that save money over the lives of the devices. Plus, plenty of incentives—offered by entities such as the federal government and your local utility—exist to help people afford the switch. Last year’s federal Inflation Reduction Act is the flashiest option, offering major tax breaks for upgrading to electrified items starting this year, but policies at the state and local levels also chip in tax credits and rebates worth thousands of dollars. Most important, “individual action can change the market,” says Diego Betts, energy programs coordinator at Walking Mountains Science Center. “The more people who want to electrify, the more businesses will respond with more and better and cheaper electric options.”

So, the question isn’t “Why electrify?” It’s “Where to begin?” Fortunately, we can help with that.

The Big Question

I can only afford one large purchase right now—which one would have the biggest impact?

Get a heat pump if…

- Your current furnace or baseboard heaters and/or central AC need to be replaced.

- You want to put in central AC where it didn’t exist before.

Get an EV if…

- You’d be replacing an ancient gas guzzler.

- You drive a lot.

- Lower-impact transportation, like biking and public transit, isn’t available or practical for you.

Get solar panels if…

- You own a single-family home.

- You want to reduce your tax liability.

- Your home has a heavy electrical load and you want lower bills.

55%: The minimum expected reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from the typical existing home in Colorado after installing a heat pump

~3%: Percentage of Colorado homes with air-source heat pumps in 2022

$1,500: Amount you’ll save annually if you replace propane heat with a heat pump. The annual savings for changing out electric resistance heating (e.g. baseboard heaters) is about $459.

Heat Pumps

Back to Top

You’d have to be a real HVAC nerd to get excited about heat pumps (which is too bad, because they represent some nifty technology). But no matter: You don’t need to study airflow diagrams to appreciate this upstart on the home heating and cooling market. These ultra-efficient electric units pull outside heat into your home during the winter—yep, even when it’s very cold out—and cool your home’s hot air in the summer. Like a standard air conditioner that also works in reverse, heat pumps use refrigerant coils to absorb heat and transfer it either inside or outside your home. Because they’re moving heat and not creating it, heat pumps use much less energy than a conventional system.

Air-source heat pumps come in two main styles: ducted and ductless, the latter of which are often called mini-splits. Ducted heat pumps “are essentially like having a central furnace,” says Neil Kolwey, director of the Beneficial Electrification League of Colorado. “Instead of having gas burners down there, you have the heat exchanger from the heat pump putting warm air into the fan system and blowing it through the house.” Mini-splits, best for spaces without pre-existing ductwork, consist of an outdoor condenser unit and one or more mounted heads inside a home that recirculate air.

Beyond the Pump

Electrification doesn’t stop at heating and cooling. Check out these three other eco-friendly appliances.

1. Heat pump water heater.

After an air-source heat pump, this has the next-biggest impact on your carbon footprint, reducing emissions by 60 to 70 percent versus an electric or propane water heater and 50 percent versus a natural gas version.

Money back: up to $1,750 in upfront discounts* and up to $2,000 as a federal tax credit,* plus some utility rebates.

2. Induction stove.

Not only are these electric appliances quicker and more efficient than their gas counterparts, but they also eliminate gas’ indoor air pollution, which can have adverse health effects. You’ll need specific pots and pans—iron or certain stainless steel—but discounts and rebates will likely cover those.

Money back: up to $840 in upfront discounts,* plus some utility rebates.

3. Heat pump clothes dryer.

These devices reuse heat rather than venting it, cutting emissions by about 28 percent.

Money back: up to $840 in upfront discounts,* plus some utility rebates.

Money-Back Guarantee

More than other electrification initiatives, heat pumps have attracted tons of incentives, some of which are income-dependent. Take this sample bill for a cold-climate-specific heat pump system for a Denver resident who makes $51,000:

Sticker price: $18,000

(Colorado’s 2.9 percent sales tax is not applied to such purchases.)

Rebates

- –$2,000: The Inflation Reduction Act’s federal tax credit is 30 percent of the system cost, up to $2,000. Mental note: If you don’t owe that much in taxes, you will not be able to enjoy this credit and will not get a refund, though any remainder credit will roll over into the next tax year.

- –$8,000: If your income falls between 80 percent and 150 percent of your area’s median income, the federal High-Efficiency Electric Home Rebate Act covers half the cost up to $8,000. If your income falls under 80 percent, the act covers the whole cost, up to $8,000. These funds will be disbursed by the states and are expected to become available in the second half of 2023.

- –$1,800: Colorado offers a 10 percent tax credit.

- –$1,000: Xcel Energy offers a rebate (up to $1,000) if your unit meets certain specs and is installed by a partner contractor.

Final price: $5,200*

*Also, after we went to press, the Denver’s Office of Climate Action, Sustainability, and Resiliency announced an additional heat pump rebate; click here for more information. Residents of some other communities qualify for other rebates. Aspenites, for example, can get another $2,500 back through the Community Office for Resource Efficiency, and Walking Mountains Science Center gives rebates to Eagle Valley dwellers.

I Made the Upgrade:

Kyri Baker, 34, Boulder

Switch: Installed a heat pump in September 2022

Prep Work: Seek out multiple bids. “The quotes we got were all over the place. Shopping around is really important, because heat pumps aren’t as established as gas furnaces. Some HVAC companies are hesitant to make the switch.” Note: Loveelectric.org maintains a list of installers who have experience with heat pumps.

Electric Cars

Back to Top

Electric vehicles, or EVs, aren’t exactly new; the first EV hit U.S. streets in the late 19th century, and all-electric cars and plug-in hybrids have been widely available since the early 2010s. But EVs seem poised for their big break: Coloradans registered more than 20,000 EVs in 2021, a 205 percent increase from just three years earlier, and that was before the federal government beefed up incentives and pledged billions for charging infrastructure in 2022.

Still, most consumers have questions. How far will EVs go? Newer, battery-powered EVs can go a median range of more than 250 miles without plugging in. How do they drive? Just like an internal combustion car—except you skip the gas station in favor of a charging station, often your garage (see below). Avoiding Conoco alone makes EVs cheaper to run, but they also require less maintenance than gas cars. According to a 2022 report from the Zero Emission Transportation Association, a gas car costs three to five times more than an EV per mile.

And they’re much greener. “Even if it’s operated on the dirtiest coal grid,” says Bonnie Trowbridge, executive director of Drive Clean Colorado, “an EV is always going to be cleaner than a gas vehicle.” Xcel Energy reports that an EV charged on its grid today produces half as much carbon as a gas car—a number that’s projected to plummet to 85 percent less by 2030.

4: Colorado’s rank among U.S. states for the most EV chargers per capita

20%–80%: Optimal range at which to keep an EV charged. It’s OK to charge fully occasionally, like for road trips, but frequent swings from low charge to high charge strain the battery.

68,652: EVs registered in Colorado as of December 7, 2022

Charge It Up

There are two main types of chargers that can be used in homes. (A third type, direct current fast chargers and Tesla Superchargers, are primarily found in public charging stations along major roads.)

Which one is right for you?

Level 1 Charger

- Plugs into the vehicle and a standard 120-volt outlet

- Generally comes standard with an EV

- Adds about four to five miles of range per hour of charging; depending on the EV, you’ll need 12 to 24 hours to fully recharge an EV

- Usually sufficient for everyday driving—roughly 50 miles a day—especially if you recharge overnight

Level 2 Charger

- Plugs into the vehicle and a 240-volt outlet (the type a clothes dryer uses)

- Costs $200 to $700-plus

- You may need to install new electrical wiring if you don’t already have the proper outlet in your garage (up to $1,500)

- Adds 20 to 30 miles of range per hour of charging and takes up to 10 hours to fully recharge\

- Great if you do lots of daily driving and for peace of mind that you’ll always have enough range to get where you’re going

Wait, What If I Live in an Apartment—or Don’t Have a Garage?

You can make an EV work even without a dedicated garage with an outlet, says Grace Rink, executive director for Denver’s Office of Climate Action, Sustainability, and Resiliency. “Most people think that if you have an EV, you need to be able to plug in at home,” she says. “But there are lots—lots—of public charging stations. And most of the time, you don’t need to plug in every night. Drivers can identify the closest charging stations to their residences, workplaces, or other places they go frequently.” Rink says it’s really just about doing a little bit of planning ahead. For example, she suggests this mindset: I’m going to be at the movies for two hours—I’ll plug in there, and I’ll be topped off for the next three days. More public direct current fast chargers are coming online, too, which are quick in comparison (at 20 to 40 minutes), making them “like going to the gas station,” Trowbridge says. ReCharge Colorado, run by the state energy office, has coaches who can help your landlord apply for grants to install a charging station at your apartment or condo complex.

Money-Back Guarantee

Tax Credits

EVs are getting more affordable. The federal government, courtesy of last year’s Inflation Reduction Act, offers a tax credit of up to $7,500 for qualifying new EVs (criteria include cost and where critical components are made, plus your income) and up to $4,000 on used ones. In addition, Colorado chips in a tax credit of $2,000 for new EVs. Check with your electric utility, too—some, such as Xcel Energy and San Isabel Electric, offer rebates to certain customers.

Installing a home charging station?

The federal government offers a tax credit up to $1,000; when funding is available, the city of Denver adds a rebate up to $1,000; and a number of utilities give rebates.

Check driveelectriccolorado.org for details.

I Made the Upgrade

Mike McLaughlin, 57, Nederland

Switch: Bought a Rivian R1T in July 2022

Prep Work: Research independent reviews from places such as Car and Driver. “From a performance standpoint, there’s always a concern about a first-generation product. What helped me overcome that was, early on, there were fantastic reviews across the board. The truck is a bit of a rocket ship to ride in. The one missing feature is that they need a sound effect of Han Solo going at lightspeed.”

In Praise of the Around-Town EV

Last year, my husband and I decided we wanted an EV. As parents alarmed about the climate-changed world our kids are growing up in, it seemed like the responsible thing to do. There was just one problem: A battery-powered vehicle with the range, cargo space, and all-wheel-drive to replace our Subaru Outback was way out of our price range. So, we cured our EV fever by keeping the gas car and adding a used 2012 Nissan Leaf as our second vehicle. With a max range of 70 miles and little space for skis, it can’t carry us on our far-flung weekend excursions, but its $8,500 price tag was much more manageable than, say, a new Subaru Solterra. Experts say this two-car plan can be a great transition into EVs, especially right now, as charging infrastructure and car technology are still improving. “We know that the majority of households in Denver have two vehicles,” Rink says. “I would encourage folks to take a look at their driving needs. If they don’t actually need to drive two vehicles a long distance most of the time, I think an EV would be a very workable option.”

It has been for us. After a year of cruising around town for preschool drop-offs, grocery store runs, and trips to the library, we found we were using the Leaf 90 percent of the time. The Outback still took us farther afield, but even then we’d go months between gas station visits (a perk made sweeter by spiking gas prices). In a few years, as more chargers pop up and car prices drop, we plan to go all-in on a newer EV with better range. Till then, you’ll find us in the Leaf. —EKH

More Options

Chevy Bolt (2023)

Style: Hatchback

Starting at: $25,600

Estimated Range Miles: 259

Subaru Solterra (2023)

Style: SUV

Starting at: $44,995

Estimated Range Miles: 228

Tesla Model 3 (2023)

Style: Sedan

Starting at: $46,990

Estimated Range Miles: 358

Ford F-150 Lightning Pro (2023)

Style: Pickup truck

Starting at: $51,974

Estimated Range Miles: 240

Lucid Air Pure (2023)

Style: Sedan

Starting at: $87,400

Estimated Range Miles: 410

Solar Panels

Back to Top

Just a decade ago, transforming sunbeams into electricity was an extremely expensive way to get power on both the utility and residential levels. Now, thanks to huge gains in scale efficiency helped along by pro-solar policies, solar is consistently the cheapest method (along with wind) for squeezing voltage from nature when sourcing new power generation. Plus, the Golden-based National Renewable Energy Laboratory says the cost to install a home system has fallen 64 percent since 2010.

All of that means homeowners in Colorado now have a great opportunity to harness the state’s purported 300-plus days of annual sunshine. That number, says John Bringenberg, board president of New Energy Colorado, a nonprofit that promotes renewable energy, happens to be true (or close enough!) and gives the Centennial State a fantastic climate for exploiting the power of the sun. Plus, plugging into solar doesn’t have to be difficult; you don’t even need to install panels on your own home to do so (see below). If you do decide to solarize your roof, however, you’ll likely generate more than enough daily juice to run your lights, laptops, and clothes dryer. We’ll concede that solar panels alter the aesthetics of your cute Victorian, but their benefits ought to inspire appreciation for the space-age touch they add to your roof.

6.2%: Amount of the state’s electricity that comes from solar

13th: Colorado’s rank among U.S. states for solar installations

452,009: Colorado homes that the state’s solar installations can power

What’s It Gonna Cost Me?

The total bill for a home solar system in Colorado will vary depending on the style of panels you choose and the size of your array, but New Energy Colorado’s Bringenberg says the ballpark cost is $18,000 to $30,000 before incentives. Expect it to take eight to 12 years to recoup your investment in energy savings—faster if your utility increases electricity prices over the years—and for your system to last 30 years or more. “Even if it is a slow payback, not doing solar has zero return on investment,” Bringenberg says. Low-interest solar loans—such as the Residential Energy Upgrade loans available from the green bank Colorado Clean Energy Fund—can help make that investment more manageable.

A policy called net metering further takes the financial sting out of a solar installation. Set up by the installer, net metering ties your solar system to the electrical grid, so that when you’re producing more energy than you’re using, you allow it to be used by other energy customers and the utility charges them for that juice. The utility then credits your solar bank (essentially your account), and when it’s cloudy or dark, you draw free power from the grid until your credits run out, at which point you’d pay the utility for that electricity.

Wait, What If I Live In An Apartment—Or My Roof Is Shaded?

In Colorado, the sun shines on both homeowners and renters alike, thanks to a very cool decade-old scheme called community solar. “[Community solar] allows people an opportunity to participate in solar and receive money, even if they can’t host the system themselves,” says Kevin Cray, the Mountain West regional director for the Coalition for Community Solar Access, a national business trade organization that promotes community solar projects. Instead, you subscribe to a centrally located solar array somewhere in your area; the project must be partnered up with your utility. In return, you can typically get 10 to 15 percent off your electric bill. As of November, there were 6,527 residential subscriptions with Xcel Energy–backed projects (the vast majority of the state’s options). Black Hills Energy also offers community solar to its customers south and southeast of Colorado Springs, and a few other small utilities may do the same, so check with your provider.

Even if you do own your roof, it might not be optimally positioned for solar panels. Or it could be too shaded by that old cottonwood. No worries: A roof isn’t the only place for panels. If you have an acre or more of land, a ground-mounted solar system could make sense, Bringenberg says. A stand-alone carport or garage can also host your array—and, bonus, keep ice off your windshield, too.

Following the Crowd

If you’re not that into poring over the details of kilowatt-hours or microinverters—that is, like most of us—then a solar co-op could be your jam. Here’s how it works: Interested homeowners sign up with a local co-op during its enrollment period. It’s free, there’s no obligation to purchase, and the co-op does all the work recruiting more members and negotiating prices and terms with a number of vetted solar installers. A committee of co-op members chooses the winning installer, who then provides customized proposals tailored to members’ household needs, usually with a significant savings due to the power of bulk buying. “It streamlines the process of going solar,” says Bryce Carter, until recently the Colorado program director for the nonprofit Solar United Neighbors, which facilitates solar co-ops across the state. “We’re able to help folks, answer questions, and address any technical issues.” Find your local co-op at solarunitedneighbors.org/colorado.

Price Changes

Xcel Energy is rolling out time-of-use (TOU) rates in Colorado from now through 2025, which means electricity will be pricier during the periods of highest demand (afternoons and early evenings) and cheaper in the nights and mornings. When the TOU program rolls out for solar homes later this year, it’ll be a boon: You’ll generate your own power as the sun shines during peak rates and draw from the grid when prices are lowest.

Money-Back Guarantee

Tax Credits

- Thank the Inflation Reduction Act once again for a tax credit good for 30 percent of the cost of a new solar system.

- Some community nonprofits (including in Pitkin and Summit counties and in the Eagle Valley) also provide rebates up to $2,500; check energysmart colorado.com for details.

- Holy Cross Energy customers can apply for an additional rebate of up to $3,400.

- The city of Denver kicks in $8,000 rebates for people making less than 100 percent of the local median income, which is $82,100 for one person and $117,200 for a household of four.

I Made the Upgrade

Greg Poschman, 64, Roaring Fork Valley

Switch: Installed solar panels in 2018 (he also has a heat pump)

Prep Work: Tighten up your home first. “We sealed every crack in the lumber, windows, and doors. That’s the first thing everyone should do. Then we put solar panels in and dropped our electric bill down to the absolute minimum.”