The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

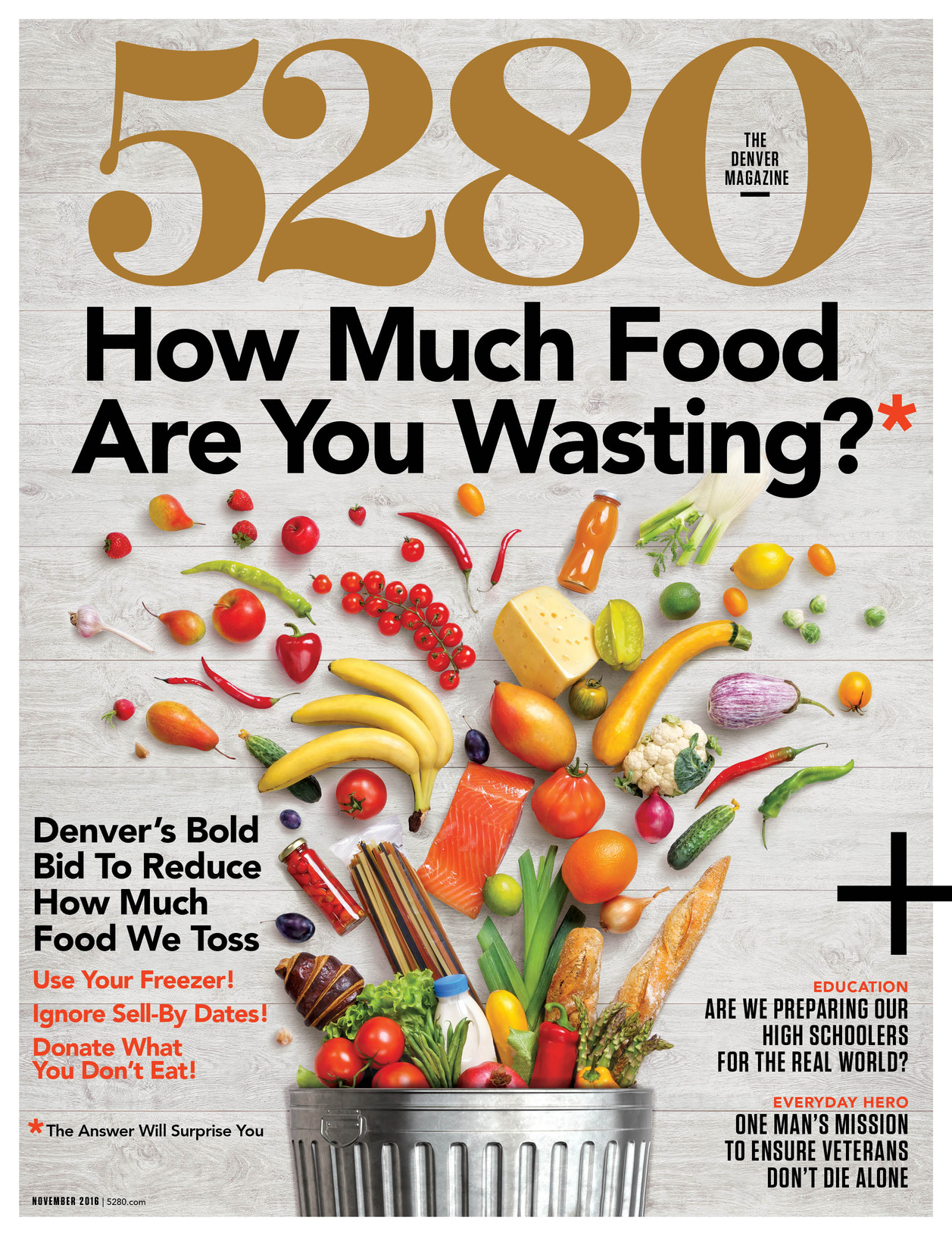

Take a moment, open up your refrigerator, and scan its contents. There’s probably something going bad in there—wilting lettuce, spoiled milk, molding strawberries. And if you’re like most Americans, you’ll probably toss the old food in the trash or down the disposal and buy more without giving it much thought.

It’s difficult to see throwing away a pint of past-their-prime berries as an outrage when the grocery store offers a virtually endless, year-round supply of fruit—and just about everything else. But discarding food should give us pause: According to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a staggering 40 percent of food produced in the United States goes uneaten, and the average family of four wastes $1,345 to $2,275 worth of food each year. When you consider one in eight Coloradans lack access to adequate food, squandering sustenance becomes a moral issue.

There are environmental consequences, too: Modern agriculture demands a significant amount of resources, sucking up 80 percent of our country’s fresh water (a serious concern in Colorado, where droughtlike conditions are the rule) as well as huge amounts of land, fertilizers, and fossil fuels. Even worse, wasted food is the most prevalent component in landfills, where it generates massive quantities of methane, a climate-change-inducing greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide.

The facts are sobering, yes—but there’s reason for hope in the Mile High City. This fall, thanks to a grant from the New York City–based Rockefeller Foundation, the NRDC is beginning a food-waste auditing program in three American cities: New York City; Nashville, Tennessee; and Denver. The program will measure the amount of food that’s currently being wasted (until now, city-specific data has never been collected), which will provide a jumping-off point for policy-based reduction efforts. In short: “Denver has the opportunity to lead this discussion,” says Adam Schlegel of EatDenver, a nonprofit that supports and promotes Denver’s independent restaurants.

While there’s much work to be done, it’s worth noting that Denver was chosen for this groundbreaking program because of the strong efforts various sectors of the community are already making to fight waste. In September, Metro Caring announced Denver’s largest-ever food waste reduction campaign in partnership with Denver International Airport, among others. And local government support for initiatives like Feeding the 5000 Front Range (an October event at Skyline Park that distributed free lunches made from 2,000 pounds of recovered food) has helped propel Denver to the forefront of food waste awareness.

Catherine Cox Blair of the NRDC cites local-level efforts led by everyone from government officials to everyday citizens to both for-profit and nonprofit organizations. On the following pages, we take a look at how Coloradans are fighting waste from field to fridge—and outline the steps we all could take to make better use of our precious nourishment. The good news: “Food waste is really a solvable problem,” says David Laskarzewski, a Boulder-based food waste activist, “and the solution is oftentimes quite delicious.”

Waste Not: Not all food waste answers are created equal. The EPA’s food-recovery hierarchy (graphic above) examines the various ways to go about decreasing waste, from the most preferable (in terms of economic benefits and reducing environmental harm) to the least.

The (Food) Chain of Events

Everyone has wasted food at home (oops, forgot about that celery!)—but to understand how we could possibly squander nearly half the American food supply, you have to start at the beginning of our complicated food system.

Agriculture

Colorado’s unpredictable weather—including late snow and destructive hailstorms—and short growing season make farming the sort of cosmetically beautiful produce retailers demand difficult. Because extensively damaged crops often aren’t worth the cost of labor to harvest, farmers frequently leave them in the fields. It’s a fate that befalls an estimated seven percent of crops in the United States, according to the USDA.

Local Diversions

- Local hunger-relief groups such as Denver-based Foraged Feast go on gleaning missions to harvest “ugly” produce from farms that would otherwise be left in the field and donate what’s gathered to food banks and pantries.

- The Fresh Food Connect website links home gardeners who happen to have an overabundance of crops with Groundwork Denver employees who’ll come pick up the veggies on bicycle. From there, the goods are distributed to Denver Food Rescue’s 12 resident-driven pop-up food pantries around the city, at which community members can access fresh produce for free. Sign up to donate at Fresh Food Connect’s website.

Post-Harvest

Produce is sorted and graded after it’s harvested. “Seconds” (specimens that are blemished, bruised, or too small) are culled, as retailers and consumers aren’t apt to buy them.

Local Diversions

- Producers that vend at farmers’ markets can often sell their seconds there.

- HB 14-1119, or the Charitable Crop Donation Act, incentivizes Colorado farmers to donate their seconds to hunger-relief organizations with a tax write-off of 25 percent of the donation’s market value.

- Seconds make good booze: In 2014, Peach Street Distillers used 450,000 pounds of fruit that wouldn’t have made it to market. Likewise, Peak Spirits (makers of CapRock gin, vodka, and brandy) is so passionate about using seconds that it received a grant from the Colorado Department of Agriculture in 2005 to pay fruit growers double the going rate for them. And this August, State38 put out a call for fruit from overproducing apple trees in exchange for discounted bottles.

Distribution

The shelf life of perishable goods is compromised if proper temperatures aren’t maintained during transport—e.g., if the refrigeration on a truck breaks down or if a truck sits too long at the loading dock.

Local Diversion

- Donation. The Food Bank of the Rockies sends its trucks to local supermarkets and has the capacity to store and quickly allocate pallets of recovered food at its massive warehouse.

Retail Losses

Goods deteriorate as they sit on supermarket shelves—especially when displayed in pyramids or manhandled by picky customers.

Local Diversion

- Alfalfa’s in Boulder makes use of damaged fruit and vegetable items in its prepared foods, especially at the juice bar. This is common practice at most stores with prepared food sections, including Marczyk Fine Foods and Whole Foods.

Food-Service Losses

Restaurant portion sizes have ballooned over the past 30 years—and much of that extra food is wasted. According to Extension (a Colorado State University educational program) agent Anne Zander, “Some portions have grown so much in size that they can provide enough for at least two adults.” Additionally, restaurants waste four to 10 percent of the food they purchase due to bad planning and unexpected sales fluctuations.

Local Diversion

- Portion smaller and smarter. For example, at Steuben’s, fries don’t automatically come with meals—customers have to order them separately. And many restaurants, such as Beast & Bottle, have nixed gratis bread service. Slimmed-down portion sizes help, too: When diners order small plates at restaurants such as Mister Tuna or Acorn, they’re more apt to eat every bite.

Consumer Losses

By the NRDC’s estimate, households throw away 25 percent of the food they buy. Dana Gunders, lead scientist for the NRDC’s food waste work, likens that process to walking out of the grocery store with four bags of food and dropping one on the ground.

Local Diversion

- Shop with a plan, store it correctly, and eat it up. Find tips in “Shop Smart, Waste Less” below.

Eat First, Compost Later

Composting won’t solve the food waste issue—but you should still do it.

PSA: You might feel like a hero when you compost, but if you’re dumping perfectly edible food that you let go bad in your fridge, you’re not exactly saving the world (see the EPA’s food-recovery hierarchy on the facing page). That said, setting up a composting program in your house or business does help keep methane-generating solid waste out of landfills. Based on figures from Denver Recycles’ 2015 report, we can infer that about 103,655 tons of compostable waste ended up in Denver landfills last year. The bottom line: Buying smarter and eating more efficiently should be your top priority when it comes to reducing food waste, but composting is still important.

Take a (free!) class from Denver Urban Gardens’ trained volunteers and learn how to start and maintain a composting operation in your yard year round. Don’t have room for a compost pile? That’s no longer an excuse: Look into Denver Composts, a program that picks up green material—yard debris, food scraps, and nonrecyclable paper—from a bin at your home each week. Currently, this service (which costs $107-$117* a year) is only available to households in certain locations, but the city is working to expand the composting program’s footprint. —Rachel Trujillo

Starting At The Source

What Colorado farmers do with “ugly” fruits and vegetables.

Kate Petrocco of Brighton’s Petrocco Farms still remembers the day a retail receiver in Texas rejected a 42,000-pound load of her farm’s acorn squash. The reason? A small portion of the crop had slightly abnormal coloring. She spent hours calling food banks—and around $2,500 paying the truck driver—to ensure that the perfectly good squash would be eaten by somebody and not end up in a landfill.

As anyone who’s ever tended a garden knows, Mother Nature doesn’t create every fruit or vegetable equally. But while the home gardener’s dimpled tomato or spindly carrot is considered a prize, the same can’t be said for produce that’s grown for markets. Thanks to retailers’ and consumers’ demands for aesthetic perfection and uniformity, plenty of perfectly edible, healthy food doesn’t ever make it to market.

Farmers don’t willingly throw away something they’ve worked tirelessly to cultivate—so how do they deal with the “ugly” harvest? That depends on what (and how much) they’re growing. Below, a look at how local farms—both small and large—find secondary or tertiary markets and crafty alternative uses for their less-than-perfect produce.

Reaping What They Sow

Hygiene, CO

Acres: 4.5

Produces: Various veggies, including tomatoes, eggplants, and greens

Percent of total harvest sold: About 75

What happens to the castoffs: They’re eaten by the Toohey family and farm staff; marked as seconds at farmers’ markets; and sold to local chefs for dishes such as gazpacho and tomato sauce.

Boulder County, CO

Acres: 130

Produces: Animal proteins and various veggies, including lettuces

Percent of total harvest sold: 80

What happens to the castoffs: What doesn’t make it to farmer Eric Skokan’s Boulder restaurants (Black Cat and Bramble & Hare) goes to feed his pigs. “Hogs are the farmer’s way of sweeping things under the carpet,” Skokan (pictured above feeding cast-off produce to his hogs) says.

Hotchkiss, CO

Acres: 176

Produces: Apples

Percent of total harvest sold: 70

What happens to the castoffs: Wacky Apples’ line of apple juices and sauces use them, and too-small apples are donated to Colorado school kids.

Brighton, CO

Acres: 2,800

Produces: Various veggies, including cabbages

Percent of total harvest sold: 70

What happens to the castoffs: They’re left in the fields and ground back into the soil, donated to food banks, or used as animal feed.

Supermarkets: Selling Unrealistic Standards

Why do stores generate so much waste?

Imagine walking into an American grocery store’s produce section and finding just a single bunch of Swiss chard or a handful of apples. That would be a jarring experience, right? In contemporary America, produce sections rely on plentiful presentations of virtually flawless goods to entice customers.

Not surprisingly, these abundant displays generate the majority of retailers’ “shrink,” or loss of inventory. The reason? Markets chronically over-order perishable items to avoid empty shelves, and displaying the product in towering pyramids can cause items to deteriorate more quickly. And that’s not to mention customers’ outrageous standards for produce.

Grocery stores in Colorado each have their own methods for diverting waste. King Soopers over-orders to keep shelves filled—but in turn, it donates truckloads (3.5 million meals’ worth per year) of culled goods to local food banks. Tony’s Market employs a similar strategy, and in addition to donating items, Natural Grocers offers markdowns on aging produce ($2 bags).

Marczyk Fine Foods takes a holistic approach to waste by repurposing ingredients in the prepared foods section (leftover buttermilk is used in the bakery, bones become soup stock). Co-founder Pete Marczyk says he has noticed employees tend to find more creative ways to use food when they don’t have the fallback of a donation system.

With their massive scopes, retailers can never hope to be zero-waste operations. But we can help get them a bit closer by letting them know that we want the chance to buy unsightly goods. A change.org petition led by Boulder activist David Laskarzewski aims to do just that: As of press time, he’d collected almost 500 signatures in favor of Walmart selling “ugly” produce.

The Dating Game

How confusing food-labeling dates lead to waste.

Best by. Use by. Sell by. Expiration dates on grocery items are more than just perplexing: They actively encourage wastefulness. In a recent study by the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, more than a third of participants admitted that they always toss food that’s past its date label, and 84 percent said they do it at least occasionally. The problem is that these dates aren’t federally regulated, and although many consumers see them as hard deadlines, they’re just the manufacturers’ estimations of when the products will be at their best quality.

Newly introduced federal legislation called the Food Date Labeling Act of 2016 attempts to remedy this. If passed, date formats would be standardized for consumer clarity, employing a two-date system (“best if used by” to denote quality; “expires on” to indicate safety). In the meantime, when you’re deciding on whether or not to trash something, just use common sense (and your eyes and nose).

Shop Smart, Waste Less

Tips and tricks from Johnson & Wales’ dean of culinary education, Jorge de la Torre.

It’s safe to say that most Americans have trouble gauging how much food to buy. Imagine, then, shopping for 759 culinary students each week, and you have an idea of the challenge Jorge de la Torre, Johnson & Wales University’s dean of culinary education, is up against.

De la Torre goes to such great lengths to avoid waste that an entire week’s worth of trash—400 pounds—fits into a single dumpster (the Denver school also employs a composting and recycling program). That may sound like a lot, but consider this: Before the university implemented solid-waste-reduction measures in 2008 and 2009, they were contending with eight tons of trash per week. “We teach students that it’s not an acceptable format to waste food,” de la Torre says.

Buying & Storing Tips

Meal Plan: If your family isn’t keen on eating leftovers, avoid them altogether by buying only the amount you need for that meal. If you’re a household of two cooking a recipe that serves four, cut it in half rather than assuming you’ll eat the leftovers.

Shop More Often: It’s hard to guess how much you’ll eat in an entire week. Instead, tackle the shopping for just one or two days out. That way, you can take advantage of sales and markdowns. De la Torre’s example: “Buy the marked-down sale meat and cook it that night.”

Shop In Season: Not only are seasonal vegetables and fruits usually priced better, but they’re also often fresher since they didn’t have to travel across the world to the supermarket. Thus, they’ll last longer in your fridge.

Prep In Advance: Dedicate time after you get home from shopping to preparing food. “Fill the sink with cold water and wash all the veggies, then dry them and chop them before storing. It pays off exponentially later on: All you need to do is add dressing for a salad.”

Store Food Properly: Dry veggies with high water content (like lettuce) thoroughly and wrap with paper towels or dish towels before stashing in the fridge; store herbs such as fresh basil or dill in water-filled vases on the counter like you would cut flowers. Bonus: “You’re more likely to use them if you see them out on display.”

The Freezer Is Your Friend: If you buy more of an item (like peaches) than you can use right away, slice them, freeze them in a single layer, and once frozen, transfer them to zip-top bags that fit your family’s portioning needs.

A Day In the Life: We Don’t Waste

An inside look the hard work of food recovery.

Like most cities, Denver has an excess of food and residents who are going hungry. Bringing the two together should be simple, right?

Well, not exactly. As Tim Sanford, director of operations at We Don’t Waste (WDW) can tell you, the actual day-to-day logistics behind recovering donated food—and getting it to those in need—is complicated.

Arlan Preblud started WDW in 2009, and he’s since grown it to an eight-employee operation that recovered and donated almost seven million servings of food in 2015. Hop aboard for the ride.

8:30 a.m.: Preblud arrives at the office on Walnut Street. As executive director of WDW, he usually spends his days here working on everything from writing grant proposals to

accounting to networking with donors and recipient agencies.

8:45 a.m.: Five other employees join Preblud at the office before heading across the street to the parking lot, where they split off into WDW’s three trucks. Sanford and staff member Morgan K. Gengenbach take the largest of the three.

9:30 a.m.: Sanford and Gengenbach arrive at their first stop, the Colorado Convention Center. They make their way through the 35,000-square-foot commercial kitchen—the largest in Colorado—to a walk-in cooler and locate the racks of food that have been set aside for them (all of it was prepared yesterday for an event and simply not eaten by attendees). They load 736 boxed lunches, four massive cakes, and 20 pounds of apples—a cash value of about $24,000—neatly into the truck, counting as they go and uploading the numbers into their tracking system by phone. This arrangement saves the Convention Center money as it would otherwise have to pay dumpster fees to dispose of the excess food.

10 a.m.: With a full truck, Sanford and Gengenbach need to quickly match the donated food to their recipient agencies since they don’t have a warehouse for storage. This is challenging since, according to Sanford, “some [of the agencies] have storage, some don’t; some have kitchens, some don’t; and almost none of them are open from 9 to 5.”

10:05 a.m.: Sanford brings the truck to a halt on Lawrence Street outside of Sox Place, a drop-in center for homeless youth. Gengenbach jumps out of the cab and pokes her head inside. “You guys want some boxed lunches?” she asks. “Sure!” says executive director Doyle Robinson. Sanford, Gengenbach, Robinson, and a few other Sox Place volunteers unload around 100 lunches and all 20 pounds of apples.

10:20 a.m.: Sanford steers the truck down the street toward the Samaritan House Homeless Shelter, a housing facility for the homeless, where WDW unloads another 100 lunches. Then it’s on to the Salvation Army Crossroads Center in RiNo, Denver’s largest homeless men’s center, where the staff takes almost 500 lunches and all four cakes.

11:15 a.m.: Sanford drops the remainder of the lunches at Denver Rescue Mission’s ministry outreach warehouse and distribution center in northeast Park Hill.

11:30 a.m.: With the truck now empty, it’s time to head to the next big collection point of the day: the Denver warehouse of Green Chef, an organic meal delivery service. A manager leads them to pallets of excess food set aside in the walk-in cooler. They’re stacked with boxes of pristine vegetables, such as organic kale, cucumbers, and broccolini, as well as packaged sauces (arugula pistou and dill-tahini) for the meal kits. Sanford passes on boxes of green beans—they’re a bit past their prime and will be composted.

12:15 p.m.: Sanford and Gengenbach spend the rest of the afternoon dropping the Green Chef bounty off at different recipient agencies across the city, including City Harvest Food Bank and Metro Caring in Denver and Thrive Church in Federal Heights.

4:30 p.m.: Sanford, Gengenbach, and the other staffers head back to the office. They clean out the trucks and enter any remaining numbers into the system before Preblud locks up.

Chef Tips

How local pros save at home and at work.

“We take leftover lemon and lime rinds from the bar and dehydrate them and grind them into powder. The powder is used for a burst of citrus flavor in spice rubs and vinaigrettes.” —Marcus Eng of the Way Back

“Fresh berries have a very short shelf life. If you don’t have time to slave over the stove making jam all day, the best solution is simple: wash, dry, and freeze them. Frozen berries are perfect for smoothies, pancakes, and baked goods.” —Nadine Donovan of Secret Sauce Food & Beverage

“I love love love soups that use old, stale bread to enrich and add a lovely velvety texture. Soups like our gazpacho, pappa al pomodoro, and sopa de ajo use this method.” —Dakota Soifer of Cafe Aion

“Save cash by making juice with vegetable trim. Buy nice whole beets, fennel, celery, etc. Trim the veggie greens and tops, cut up a couple of apples and lemons, and send it all through the juicer.” —Jorel Pierce of Stoic & Genuine

“Any leftover vegetables and fruit we can’t use immediately, we pickle, including ‘throwaways’ like watermelon rinds, bok choy stems, and Swiss chard stems. Excess beef fat from the butchery program is used for tallow candles.” —Hosea Rosenberg of Blackbelly Market

“Take stock of your pantry and do an intervention. What do you actually like to eat and cook? Your pantry should be like a closet—you don’t need Uggs if you live in Florida.” —Eugenia Bone, author of the Kitchen Ecosystem

“Corncobs and husks make great stock to use to cook rice, polenta, potatoes, legumes, etc. We smoke them and use them to make a stock for our corn soup at Root Down.” —Corey Ferguson of Root Down

“When I cut the skin from salmon, I lightly brush some soy or teriyaki (or just kosher salt) on it and roast it until it’s crispy. It’s great as a snack or chopped in a salad.” —Troy Guard of TAG Restaurant Group

“You can resuscitate wilty vegetables! Lettuces and some vegetables like celery can be brought back from a wilted state by letting them soak in cold water for a few minutes.” —Dan Long of Mad Greens

“When you have leftover cinnamon rolls, muffins, or croissants, throw them in a zip-top bag in the freezer until you have enough to make a pan of bread pudding.” —Elise Wiggins of Cattivella

A Food Waste Diary

What I learned from completing six weeks of the EPA’s Food: Too Good to Waste Challenge.

How much food do you trash each week? It’s a vital question—and one I didn’t know the answer to. “People often waste more food than they think,” says Virginia Till, the EPA’s Region 8 representative, recycling specialist, and sustainable food management lead. To find out exactly how much food my household of two was really squandering, I signed on for the Food: Too Good to Waste Challenge, a free six-week toolkit that allows anyone to measure—and take pointed efforts to reduce—waste. Here’s what I learned.

Week One

Total Amount of Food Wasted: 2 pounds, 4.28 ounces

Per the challenge guidelines, we set up a collection bag in our fridge (I used a paper grocery bag lined with a compostable plastic bag), where we disposed of our “preventable food waste,” defined as any edible food that spoils, not including inedible bits like banana or orange peels. At the end of the week—and every subsequent week—we weighed how much we had accumulated. The average American wastes around 20 pounds of food per month, meaning that the typical household of two wastes nine pounds per week. I was happy to learn that our initial measurement was well below that number. Still, just having to actually look at the two pounds of food we tossed (mostly leftover prepared food) made me feel guilty.

Week Two

Total Amount of Food Wasted: 1 pound, 14.32 ounces

I love to bake, but most recipes yield more treats than two people can eat. As a result, I’m tossing a significant amount of home-made sweets. Perhaps my worst offense of the entire challenge: letting about half of a Colorado cherry crumble go moldy after a few days of sitting on the counter, unrefrigerated. I paid almost $8 per pound for those cherries, too. Shame.

Week Three

Total Amount of Food Wasted: 1 pound, 13.92 ounces

We started implementing the EPA’s “smart strategies,” which included creating a “Meals-In-Mind” shopping list (a template for creating a more mindful shopping list based off of meal planning); employing better storage tactics to extend the shelf life of produce; prepping food right after shopping so that it’s ready to use; and creating an “Eat First” shelf in our fridge where we can display the items that are most in need of being eaten (highly perishable berries and greens, leftovers on their ways out). I quickly realized that thanks to my job as a food editor, meal planning doesn’t work well for me. I only ate dinner at home twice during the week because I was out reporting.

Week Four

Total Amount of Food Wasted: 1 pound, 1 ounce

Four weeks in, we became more diligent about prepping and storing our food. The salad spinner was my new post-grocery-store best friend as I took up the practice of washing and drying all of my greens before storing them in the fridge, which both extends their shelf life and makes us more apt to eat them later in the week. Also, we learned that just about any odd bit of leftovers can be thrown into scrambled eggs.

Week Five

Total Amount of Food Wasted: 3.72 ounces

I had fewer dining commitments than usual and spent more time in the kitchen prepping, storing, and cooking food. The Eat First shelf also helped our total go down. One evening, instead of shopping for and cooking a whole new dinner, I ate leftovers instead. It wasn’t my first choice, but it saved me both money and time.

Week Six

Total Amount of Food Wasted: 1 pound, 1.53 ounces

While our overall total was still down from the first week, we tossed lots of uneaten restaurant leftovers. We cleaned out the condiment shelves and chucked a couple of moldy jars of pickles and jam. On a positive note, I started using my freezer more efficiently to store food I couldn’t eat immediately, and I managed to make a few jars of pickles and preserves from some of the produce I bought.

The Takeaway: Initially, during weeks one and two of the challenge, we wasted an average of two pounds, 1.3 ounces of food per week. After we implemented the reduction techniques, we whittled that down to an average of one pound, one ounce per week for weeks three through six. Although we didn’t become a zero-waste household, we effectively cut our food waste in half over the course of the challenge. And it wasn’t actually all that difficult. It required a bit of mindfulness and a change in perspective, and in all instances, it saved us both time and money. Since finishing the challenge, we’re no longer collecting and measuring our household waste, but the lessons have endured. As I type this, I’m eating an oddball amalgamation of leftovers I salvaged from my fridge for lunch. It’s not the most cohesive meal I’ve ever had, but there’s something pretty fulfilling about respecting the food by actually eating it. Till sums it up best: “Food is valuable not only in terms of our wallets, but our experience as humans.”

Want to take the challenge yourself? Find all the materials at the EPA’s Sustainable Management of Food website.

Editor’s Note 11/1/2016: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the cost of the Denver Composts Program. We regret the error.