The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

To reach the official start of the High Line Canal, I have to follow a wide dirt road two miles into Littleton’s Waterton Canyon. Yellow warblers whistle among the cottonwood trees, and bikers and walkers of all ages meander the same path, escaping into the wilderness at lunchtime on a Wednesday. Forty minutes later, I arrive at an S-curve in the South Platte River, where, in the late 1880s, a dam and 600-foot-long tunnel were built to divert water toward the nascent settlements of Gold Rush pioneers. This spot marks Mile 0 of the High Line Canal trail, a greenway that covers more area than New York City’s Central Park.

Read More: High Line Canal to be Transformed with $100 Million in Investments

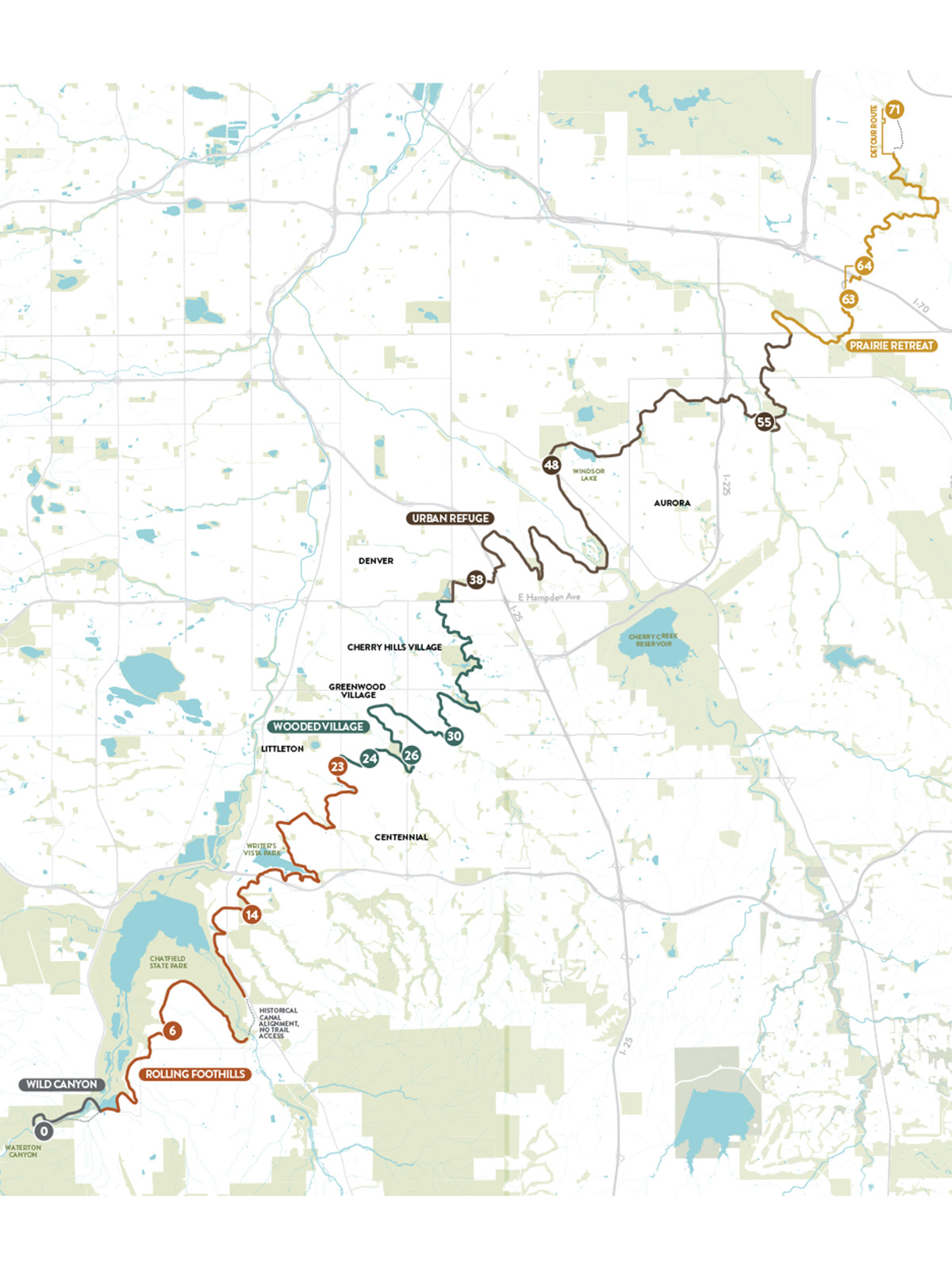

The 71-mile-long canal crosses through 11 jurisdictions and over and under three highways as it weaves northeast from Waterton Canyon to Aurora, almost reaching Denver International Airport. Along the way, it tells the story of the transformation of “the great American desert into a major metropolis,” says Tom Noel, aka Dr. Colorado, a professor emeritus in history at University of Colorado Denver.

More than a century ago, the canal was built to carry irrigation water to farmers. Today, the one-time ditch rider’s road—the route people on horseback (and, later, Model T’s and trucks) followed to manage water delivery—has evolved into a playground for the tens of thousands of people who live near it. But because the High Line wasn’t designed as a trail, way-finding can be difficult, and there are gaps and deviations along the path (e.g., the fact that you have to start at Mile 2 to reach Mile 0, then double back if you want to say you traversed the whole thing).

Thankfully, connectivity is on its way. Eleven years ago, the High Line Canal Conservancy was formed to lead planning efforts as the thruway morphed from a water utility into a regional recreational amenity and stormwater management corridor for the Front Range. The nonprofit and local government partners will oversee more than $100 million in trail investments over the next five years. Those funds will increase neighborhood access points, enhance signage, create safer crossings, restore natural resources through invasive species removal and tree plantings, and build pocket parks and shade structures.

More than 60 percent of those dollars will be used in the northeast segments—27 miles that cross Denver and Aurora and have been historically underinvested in. That’s due to both the lack of canal water that flowed that far and the socioeconomic realities of the nearby communities, which didn’t have the funds to devote to beautification projects and were less likely to be included in planning processes. That’s changing, as many of the forthcoming initiatives were developed with neighborhood input. “The projects themselves will improve the trail as a more comfortable and welcoming space to be in,” says Suzanna Fry Jones, the conservancy’s chief programs and impact officer. The goal, she adds, is for the trail to become a community amenity.

And, of course, for more people to discover the beauty of the ditch. The High Line remains relatively unknown to many Coloradans: Even those who live along it and consider it their backyard trail may not realize the full scope of the canal, Fry Jones says. Here, our guide to exploring the route today—and for years to come.

Jump Ahead:

- History

- Best parts of the trail

- Where to go by activity

- Cycling the trail

- Tips for hiking the trail

- Side trips

- Improvements

- How to help

History of the High Line Canal

- 1881: As the Front Range’s population booms following the Gold Rush, James Duff, a Scot, and Benjamin Harrison Eaton, an entrepreneur who became the governor of Colorado, realize there might be money to be made by moving water from the South Platte River to the region’s farmers and ranchers. The project is financed by British investors operating as the Northern Colorado Irrigation Company, and construction of the High Line Canal begins.

- 1883: The hand-dug canal is completed. Its name derives from an engineering principle that relies on terrain and elevation change to move water via gravity. The ditch drops two feet per mile as it follows the high points of the topography, which explains its seemingly random, curving configuration.

- 1924: The utility now called Denver Water acquires the High Line for $1.05 million. At its peak, the corridor helps irrigate more than 20,000 acres.

- 1970: After years of rule-breakers tubing (still prohibited), walking, cross-country skiing, and otherwise enjoying the canal, Denver Water lifts some restrictions and begins conversations about creating an official recreational trail.

- 1975: The canal is designated a National Waterworks Landmark.

- 2014: The High Line Canal Conservancy is created to develop a comprehensive plan to preserve the route.

- 2024: Forty-five miles of the High Line are transferred to Arapahoe County with a conservation easement, meaning they’re permanently protected as open space. (Denver Water still owns a majority of the remaining miles, which it hopes to permanently protect.)

- The waterway has long struggled to achieve its initial purpose. Denver Water still has customers along the High Line, but the utility hasn’t run water for them since 2021; the canal’s relatively junior water rights mean there’s rarely any available. Even if there were, around 70 percent of water sent via the route is lost to seepage or evaporation. “The canal is an inefficient way to deliver water in the 21st century,” says Josh Phillips, the High Line Canal Conservancy’s senior director of planning and implementation.

The Best of the High Line Canal

- Mile 0: The High Line Canal begins at a 145-year-old diversion dam. Those who want to hike the full length need to walk two miles into Waterton Canyon to the dam, then turn around and walk back to Waterton Road and cross the street to link up with the rest of the trail.

- Mile 6: As you saunter past Denver Polo Club, make sure to yield for the horses (and their riders) that frequent this section.

- Mile 14: Three historical wooden flumes—bridgelike structures that once conveyed water over lower elevations—remain on the route, including one that sits above Mary Gulch at Mile 14. (A second, the Bennett flume, is at Mile 17.5.)

- Mile 14.5: It’s possible to grab some free snacks along the trail in September and October, courtesy of apple, pear, chokecherry, and plum trees near Fly’n B Park.

- Mile 23 to 24: Keep your eyes peeled for the Imagination Tree (a wooden sign, painted rocks, and various baubles are clues you’re looking at the correct cottonwood), which inspired Centennial residents Joan Bast and Joanie Bolton to pen The Imagination Tree! Where Dreams Begin!, a 2024 children’s book.

- Mile 26.25: You’ve reached one of the most photographed spots on the canal: a bench designed to look like the front seat of a wagon. Sit down and look for the eagles and great horned owls that sometimes hang out in the area.

- Mile 30.5: There were originally 165 head gates to control water flow along the canal. You can still see many of them, including number 69 here (which is black and orange but missing its wheel on top), if you keep a close eye on the ditch as you walk.

- Mile 38: Public art, like the “High Line Sunrise” painting by local father-and-son team Jay and Jerry Jaramillo that decorates the I-25 underpass at Mile 38, is present all along the canal. (Ceramic birds hide at Mile 29; carvings made into old cottonwoods sit between Miles 39 and 42; and clouds hang above a pedestrian bridge at Mile 54.)

- Mile 48: Fairmount Cemetery is Denver’s second oldest and the final resting place for 19 governors plus other notable figures in the city’s history, such as Emily Griffith and Helen Bonfils.

- Mile 52: In 1993, Robert Michael Pyle published The Thunder Tree, a memoir about growing up and adventuring along the High Line in the 1950s and ’60s. The tree that inspired the title still stands here.

- Mile 55: Take a quick detour and walk the short path to the DeLaney Round Barn. Built in 1902, it’s on the National Register of Historic Places and thought to be the last remaining structure of its kind in the state.

- Mile 63.5: Photo op: A faded wooden boat is an unexpected sight in the prairie.

- Mile 64: Completed in June 2024, this pedestrian bridge closed one of the last remaining trail gaps along the canal.

- Mile 71: Technically, the last segment of the High Line is not open to the public, so anyone looking to complete the full route will have to rely on a trail detour to nab 71 full miles—at least for now. Plans for a new housing development include access to the ditch and will move the trail’s end closer to its original termination point.

Read More: Our Favorite Sites Along the High Line Canal Trail

Where To Go for…

- …history: Wild Canyon (Miles 0–2): As you hike or bike to the diversion dam that marks the ditch’s start, you’ll see current Denver Water equipment as well as buildings from the historical Kassler Water Treatment Plant, Denver’s first such facility. Also look out for the herd of Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep that lives in the canyon. Partly so as not to disturb them, note that ADA exceptions aside, there is no public motorized access—including via electric bikes—on this portion of the trail.

- …birdwatching: Rolling Foothills (Miles 2–23.5): There are more than 30 birding hot spots along the canal. Platte Canyon Reservoir, between Miles 2 and 3, showcases some of the greatest diversity of species; keep an eye (and an ear) out for spotted towhees, Western kingbirds, and double-crested cormorants.

- …horseback riding: Wooded Village (Miles 23.5–37.5): Under the shade of cottonwoods, the spacious paths in this zone and the nature preserve it passes through (as well as the views into Cherry Hills Village backyards) create a bucolic setting for a leisurely ride.

- …cycling: Urban Refuge (Miles 37.5–60): The hard-surface trail will be easy on your wheels, plus this swath offers connectivity to a number of neighborhood and regional routes, including the Cherry Creek Trail.

- …wildflowers: Prairie Retreat (Miles 60–71): The prairie may seem like an unlikely place to view flora, but in 2023, a group of conservancy volunteers deposited 173 native prairie plants in a wild garden near Mile 65, where you can spot scarlet globe mallow, spiderwort, and prairie coneflower. Of course, blooms abound throughout the canal, from blue ridge carrion flowers in Waterton Canyon to the perennials planted by the senior community that abuts the High Line near Mile 49.

Cycling the Whole High Line Canal Trail

It was while I was holding my bike overhead, navigating waist-deep water in a marsh next to Plum Creek in Littleton, that I realized I didn’t know a thing about the High Line Canal.

Living on the west side of Denver, I’d heard about the storied urban route, but I’d never had much reason to explore it. So, when I decided to ride the entire trail over the course of two days, I didn’t realize that it was 71 miles long or that only about half of it was paved. Or, as I was experiencing firsthand, that those miles aren’t exactly connected.

I started on a Friday afternoon on my road bike, beginning where the trail technically ends—just east of Peña Boulevard, across from the Gaylord Rockies Resort & Convention Center. I followed the High Line Canal Conservancy’s map, cruising a concrete path through a suburban neighborhood, then a gated golf course community. I rode alone and passed few others along the way. Prairie dogs and wrens were my most frequent companions.

A few miles in, the path became more wooded, and I saw my first official High Line Canal trail sign. Despite that marker, route-finding proved challenging, requiring me to cross busy streets like East Colfax Avenue and hopscotch across sidewalks. I found that the canal itself became the best way to get my bearings. Whenever I started to worry that I’d made a wrong turn, I’d seek out the low-flowing ditch and carry on. Three hours of cycling later, I reached my destination: Denver’s Mamie D. Eisenhower Park. Thirty-three miles down.

When I returned to the High Line on Memorial Day, I did so with company (my 75-year-old uncle, Pat). We hopped on our gravel bikes at the Waterton Canyon parking lot and rode to the dam and the official start of the trail. (Note: E-bikes are generally not permitted on this portion.) As we cruised along the first nine, muddy miles, I thought my canal woes were behind me. Then we saw a sign that indicated the route would dead-end southeast of Chatfield Reservoir due to private property. (Plans to connect what’s known as the Plum Creek gap are underway; see below.) The way-finding map didn’t offer a detour, and we didn’t think to double back through Chatfield State Park.

Which is how we found ourselves traversing a quick-flowing creek. Once we crossed the water and climbed the embankment, we reunited with the High Line alongside U.S. 85—bewildered, soggy, and with pebbles in our shoes.

The remainder of the ride was less eventful and surprisingly beautiful, given its urban location. We rode a mostly gravel trail through parks and nature preserves and ogled perfectly manicured backyards in neighborhoods I’d otherwise never have visited. By the time we reached Colorado Boulevard again, we had traveled 42 miles. We never left the metro, but I felt like I’d been worlds away. —Jay Bouchard

5 Tips for Hiking the High Line Canal Trail

The High Line snakes through six cities, meaning thru-travelers (aka High Liners) can’t camp but can access creature comforts along the route. We asked conservancy board member Debi Hunter Holen, who has walked the full length over a three-day span multiple times, for her tips.

- Wear sneakers: Hiking boots are designed for uneven trails, not paved walkways. Sneakers work just fine on the High Line. An extra pair of socks never hurts, though.

- Pack light: Carry snacks and enough water for the day, but between public parks, main arteries, and general access to urban amenities, you don’t need to load up as if you’re going off the grid. (Hunter Holen’s favorite trail snack? Hi-Chews.)

- Get to know the canal beforehand (and take the conservancy’s trail map): Because it wasn’t originally designed as a trail, the High Line can get a little wonky. There are still gaps in the route, and way-finding kiosks can be intermittent (though the conservancy has added more than 180 signs and mile markers, with more to come). Three sections, including the start of the trail in Waterton Canyon, require you to retrace your steps (go out and back) to log every official mile because the trail is disconnected. Heads up: That also means you’ll actually be walking a few more than 71 miles.

- When you see a bathroom, use it: The southwest portion of the trail has plenty of toilet access, but latrines become sparser after you pass James A. Bible Park. Look for public toilets in parks or at area businesses; there’s also one at Fairmount Cemetery.

- Indulge in some pit stops: Hunter Holen’s favorite bakery—Manna Bakery & Deli—is just across the road near Mile 22. If your feet aren’t too worn out, side trips for a treat (and a seat) are easily accomplished. Other ideas: Sonder Coffee & Tea is 0.3 miles off the trail, near Mile 46, and Dry Dock Brewing Co. sits just past Mile 63.

The Best Side Trips Along the High Line Canal

- Swimming hole: Head into Waterton Canyon via the Origin Trail. The diversion dam—about two miles down a wide, dirt road—is a great spot to cast for rainbow and brown trout or splash around. Shaded picnic tables are made for snack time.

- Playgrounds: A number of playgrounds are accessible just off the canal, including at Writer’s Vista Park (Mile 18.5), Expo Park (Mile 50.25), and Norfolk Glen Park (near Mile 59.75).

- Disc golf: Expo Park’s disc golf course parallels the canal. Beware: The venue is known for its water hazards.

- Horseback riding: Explorers ages seven and older can join Littleton’s Sagebrush Stables for a two-hour, historian-led trail ride along the canal’s southern stretch.

5 Improvements Along the High Line Canal

1. Student Amenities

- Expected Completion: 2026

- Where: Miles 57–59

- What: The canal passes by Aurora’s William C. Hinkley High School and Laredo Elementary School. In response to community input, shade structures, an outdoor classroom, an overlook at Granby Ditch, and more will be added to improve access to the corridor and inspire students to spend time in nature. A new art project, around Mile 58, will also see dead and dying trees transformed into sculptures; area students helped Chilean-born artist Adolfo Romero complete the works.

- Why: The northeast stretch of the High Line is less developed than earlier segments. In December 2022, the High Line Canal Conservancy launched a group called the Northeast Advisory Committee to lead community focus groups and help implement what it calls “priority improvement projects.” This is one of them.

2. Flood Mitigation

- Expected Completion: Ongoing

- Where: Entire canal

- What: It may not be a sexy topic, but stormwater (water resulting from rain or snow) is part of the future of the canal, an obvious landing point for runoff that doesn’t seep into the ground. A multiyear project, currently in the planning stages, is underway to add green infrastructure like berms and constructed overflows to manage potential spill locations.

- Why: Better stormwater management mitigates flood risk while also supporting animal and plant habitats and reducing the urban heat island effect.

3. Safer Road Crossings

- Expected Completion: 2028/2029

- Where: Mile 59

- What: The first of three East Colfax Avenue crossings is set to get an upgrade in the next couple of years: an underpass at the road’s intersection with Laredo Street that will make the spot much safer. (Users, including area schoolkids, must currently walk across a road with no lights or crosswalks.)

- Why: The High Line Canal trail makes 100 street crossings, some of which force users to navigate heavy vehicle traffic. A number of major crossings, such as Hampden Avenue and Colorado Boulevard, have seen underpasses added in recent years, and more are on their way, including at East Yale Avenue and South Holly Street.

4. Connectivity

- Expected Completion: TBD

- Where: Miles 9.75–11

- What: Douglas County is studying alternative approaches to connecting one of the last remaining gaps along the canal, but an exact plan for how to address the break is still in the works.

- Why: Plum Creek has a significant trail interruption where private property forces users trying to log as many official canal miles as possible to do a confusing out-and-back from Roxborough Park Road trailhead, then pick the route back up near Mile 11.

5. Interpretive signs

- Expected Completion: TBD

- Where: Miles 0–2

- What: To better tell the origin story of the High Line Canal, improvements are planned for the trailhead, and additional interpretive signage and two overlooks are in progress. Douglas County will eventually build a short connector trail between the trailhead that goes to the origin point and the start of Mile 2, which are currently separated and require a short walk down Waterton Road.

- Why: For such a major historical site, there are almost no indicators of where you are beyond a single sign at the diversion dam. Many users are likely exploring Waterton Canyon versus purposefully setting out on the High Line—a reality the conservancy would like to change.

Read More: The Creation of the High Line Canal Conservancy

3 Ways To Support the High Line Canal

- Join a High Line Canal Conservancy–hosted cleanup or brush-removal event to help beautify the canal, keep it safe for visitors, and reduce fuel for fires. (A self-directed cleanup program, where you grab the necessary supplies at the conservancy’s canal-adjacent office in Centennial and pick up trash on your own walk, is available too.)

- Make the canal more accessible for all by conducting a walk audit to evaluate pedestrian safety. (The worksheet is accessible on the conservancy’s website, highlinecanal.org, and can be completed on your own time.)

- Buy a ticket to the conservancy’s annual fundraiser, Dine for the High Line, on September 12.