The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

We live in a “shake it off” culture. Dads bark the familiar phrase from the bleachers. Coaches tell their young charges to “rub some dirt on it” and order them back into the game. We value strength and durability in our athletes—even our Pop Warner warriors. It’s a norm that University of Denver clinical associate professor Kim Gorgens laments. As a specialist in brain injury, Gorgens knows all too well the danger of ignoring any sports-related injury, especially ones involving the brain.

Our “tough love” approach leaves young athletes susceptible to concussion-related injuries ranging from persistent headaches to death. In fact, the 2010-11 National High School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study, conducted by the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio, reports that 249,653 high school athletes suffered a concussion during the 2010-11 academic year. But Colorado has a new weapon against such head trauma cases, making the state among the most aggressive in protecting athletes as young as 11.

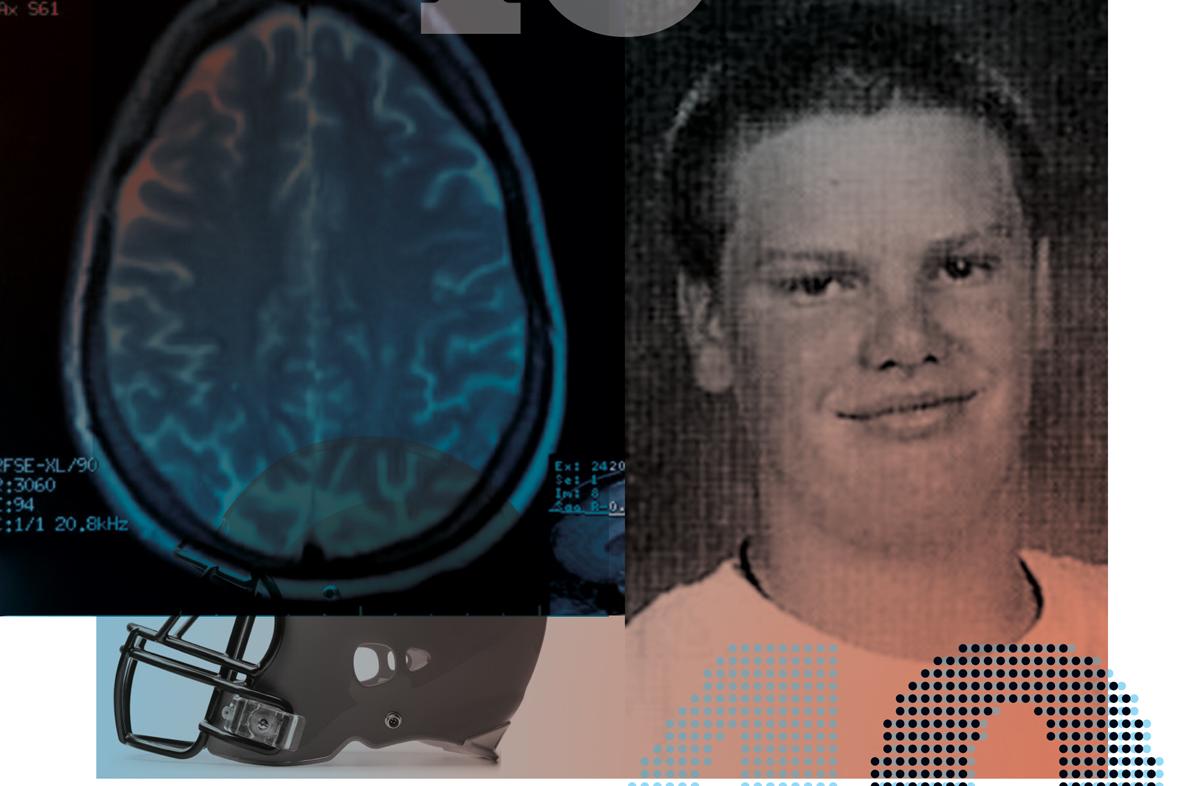

The Jake Snakenberg Youth Concussion Act (SB11-040), named after the Grandview High School student who died in 2004 after suffering head trauma during a football game, mandates all coaches in public and private youth sports complete an annual concussion recognition course. The act, which goes into effect this month, also means middle and high school students suspected of suffering a concussion cannot return to action without written clearance from a health-care provider. The legislation, signed by Governor John Hickenlooper in March 2011, complements the state’s existing REAP program (Reduce, Educate, Accommodate, and Pace) which provides free guidance for teachers, parents, coaches, and medical staff on how to immediately treat concussed athletes.

DU’s Gorgens, who helped craft the Youth Concussion Act, says treatment plans for concussed athletes continue to evolve. But she says there are a few things everyone should understand. Repeat blows to the head should be avoided—period. In an effort to prevent further traumas, the University of Denver created a concussion alert wristband for injured athletes. The gold-colored band lets people know the wearer has suffered a recent concussion and should be treated with care to avoid a second jolt to the head. (Jake Snakenberg’s death may have been due to a first, undiagnosed concussion compounded by the hit that killed him.) “As an athlete you see someone in a boot, and you say, ‘Oh, you’re hurt.’ But with concussions there’s nothing you can see,” says Andrew Hooper, a 22-year-old DU graduate who missed much of his senior season on the basketball team as a result of a concussion.

Gorgens also explains that recovery from a concussion isn’t as immediate as many people think. “In much the same way we advise a graded return to physical activity, there should be a graded return to mental activity,” she says. Parents of a concussed athlete should consider implementing a gradual return to schoolwork, texting, and surfing the Internet. In these cases, those sensory demands should be thought of like any other traditional exercise, she says.

The concussion discussion has been getting attention across the country in recent years, especially with some former NFL players joining the crusade to prevent these types of injuries. Gorgens is glad to see it, and she’s thrilled that even the popular Madden NFL 12 video game by EA Sports factors in concussions. “You hammer the message home early on as kids pick up organized sports,” Gorgens says, “and it becomes part of the sporting culture.”