The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

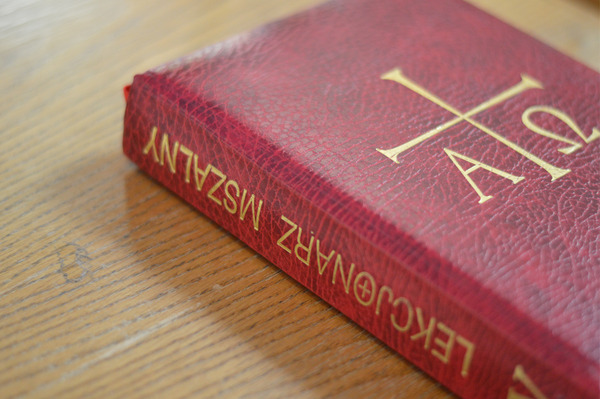

As immigrants settled in Globeville, they quickly built churches (and saloons) to make the new country feel a little bit like the old one. One of those religious spots, St. Joseph Polish Catholic Church, still holds some services in Polish. Click through the gallery above for a tour.