The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

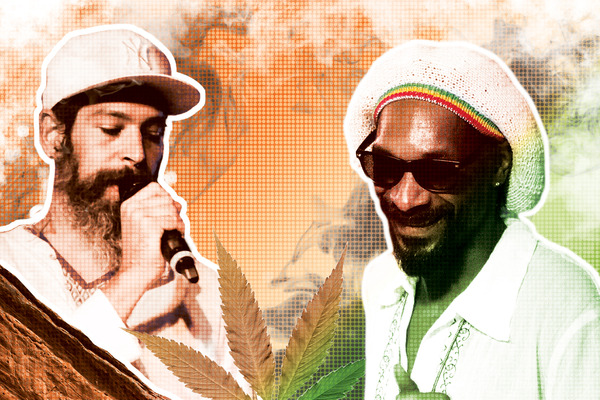

On April 20, the hallowed stoner celebration day known as 4/20, rappers Snoop Dogg and Wiz Khalifa headlined at Red Rocks, and reggae rapper Matisyahu joined MC Talib Kweli at the Fillmore Auditorium on East Colfax. The previous day, jam bands Karl Denson’s Tiny Universe and Dumpstaphunk were in LoDo. It may not have been a weekend in New York City—but it wasn’t bad for a couple of spring days in the Mile High City.

“It seems as if musicians are viewing [shows in Colorado] like an Amsterdam tour,” Jay Bianchi, owner of local clubs Sancho’s Broken Arrow and Quixote’s, told me when I called him earlier this year. Which is really just a roundabout way of saying they’re looking for a place to buy and smoke pot indiscreetly without fear of getting busted.

Bianchi isn’t the only observer of the local music industry with this theory. I’ve been covering the music business as a Denver-based contributor to Rolling Stone for more than a decade, and before Colorado’s marijuana law went into effect in January I’d predicted a flood of musicians who would instruct their agents to ensure tour stops in Colorado. I also expected hordes of out-of-town fans booking flights and hotels to hear them play.

But Matisyahu, speaking from a tour stop in Miami, made a different case, as did numerous agents, managers, and concert promoters to whom I floated the “pot + musicians = tourism” equation. “I don’t think anything will change,” Matisyahu said. “Denver has always been the gateway to the West, in terms of the routing. It’s always been a place that bands will go.

“But whoever the stoner is in the band—he is looking forward to going to Denver,” Matisyahu laughs. “Mainly, it will affect guitar techs across the country.”

The truth about Colorado’s music scene is that it never, ever turns into the next Seattle or the next Portland or the next Detroit. The transformation didn’t happen when the Eagles picked (the now-defunct venue) Tulagi as its home base in Boulder. It didn’t happen when the Samples and Big Head Todd and the Monsters threatened to turn the state into an international jam-band metropolis. It didn’t happen when the Fray and the Flobots had their hits. And it appears as if it’s not going to happen now, even if Snoop and Wiz can walk into a storefront on South Broadway to load up on chronic. “[Marijuana] might be a nice perk once you’re there, but it’s not really the reason we’re going,” says Peter Schwartz, the New York booking agent for numerous hip-hop stars, including hemp-friendly rappers such as Khalifa, Cypress Hill, and Redman. “And let’s keep in mind, realistically, that people who enjoy marijuana have it. They don’t really need to go to Colorado for it.”

On top of that, consider Colorado’s restrictive rules about pot use: You still can’t smoke anything (legally) at a public concert (that includes cigarettes and cloves); you still can’t (legally) smoke weed in a public place; and you certainly can’t (legally) bring ganja on an airplane or carry it into a neighboring state. “Most musicians are talking about it, and we’re all pretty psyched on it,” says Marco Benevento, an indie musician based in Woodstock, New York, who is so associated with marijuana that fans approach after concerts to gift him with edibles and vaporizers. He adds, though, that pot smokers crossing the Centennial State’s lines have to be more careful than ever. “We’re also kind of scared to drive in and out of Colorado,” he says. “We’ve heard people are getting busted around borders and whatnot.”

Still, music promoters here have tried to lure crowds with cannabis—although perhaps not in the way most would expect. In April, the Colorado Symphony Orchestra announced three summer bring-your-own-pot shows sponsored in part by a promoter called Edible Events. “Part of our goal is to bring in a younger audience and a more diverse audience, and I would suggest that the patrons of the cannabis industry are both younger and more diverse than the patrons of the symphony orchestra,” Jerry Kern, the symphony’s executive director, told the Denver Post.

By May, city officials threatened to shut down the event due to a concern that classical music fans might commit the illegal act of toking up in a public concert venue. In the end, the symphony retooled the concerts into private events—the first of which raised $50,000 through sponsorship and donations. The scrambling at the time led to mixed messages among symphony officials. This spring, I spoke with a vice president who backed off Kern’s statements. But in June, Laura Bond, the CSO’s public-relations director, reverted to Kern’s sunnier spin: “People are coming here for music as a destination—if marijuana helps sweeten that profile, we’re all for participating in that.”

Even if Denver isn’t poised for a weed-driven music boom, perhaps that’s not a bad thing. And, indeed, something more gradual—and exciting—may be in the making. As of early May, the state had collected more than $25 million in marijuana taxes and fees in 2014. If the economy gets a boost, more people will have more money to pay for more concert tickets. (Corinne Henahan, the publicist for an Ohio band called Ekoostik Hookah, tells me the band’s Colorado fan base has recently grown, which she attributes to the new pot law—because, you know, the band’s name is Ekoostik Hookah.) And if more people go to more concerts, that means more venues and more shows, eventually. “When you create a healthy financial environment, which is what I think is happening there, people have more money to spend on fun things,” says Karl Denson, the San Diego–based frontman for Tiny Universe, which plays regularly throughout the Centennial State.

Benevento is even more optimistic about this potential Colorado windfall. His wishful theory is that pot will generate so much income local businesspeople will start to open more music clubs, and those who already own them will start to spend more money. Plus, Colorado might attract more free-spirited creative entrepreneurs who would open more clubs, hire more bands, and generally contribute to the state’s utopian post-prohibition atmosphere. “Maybe club owners will be like, ‘Hey! We can totally have you come in! We can totally afford a piano and some plane tickets for you!’?” Benevento says.

That may be a stretch, but consider this: One band recently stipulated in its concert rider that Bianchi, the owner of Quixote’s and Sancho’s, provide cannabis-infused edibles backstage. Bianchi’s response? “OK.”