The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Most museums acquire their fossils in expeditions, with scientists often traveling hundreds or thousands of miles to badlands or other far-flung regions where teams prospect for remnants of ancient life. But paleontologists at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science only had to look in their north parking lot—or, more precisely, some 700 feet beneath it. Last week, the museum announced that drilling for its geothermal project had led to the discovery of a 67.5-million-year-old partial dinosaur bone from deep below City Park, calling it “Denver’s deepest dinosaur” in a paper published in the journal Rocky Mountain Geology in June.

“It is incredible luck. It’s the luckiest luck of all,” says James Hagadorn, the museum’s curator of geology. “I had a wishlist of what I hoped we would find when we drilled this core, and a dinosaur wasn’t even on it.”

The greater Denver area is well-known for its dinosaurs. The town of Morrison, about 20 miles to the museum’s southwest, is famous in paleontological circles for the astoundingly well-preserved formation that bears its name: a swath of 150-million-year-old Jurassic-era rocks that helped fuel 18th-century fossil feuds and led to the discovery of iconic species including Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, and Brontosaurus. (Denversaurus, an armored tank of a dinosaur that’s named for—and on display in—the Denver museum, sadly was not found in the state.)

The city itself has few exposed rock formations from the time of the dinosaurs, Hagadorn says. The upper 30 feet or so under City Park are composed of sand, gravel, and soil, deposited by the runoff from the Rocky Mountains during the last Ice Age. But buried deep beneath are remnants of a more ancient world: sandstones and mudstones left over from the millions-years-old floodplains and forests of the late Cretaceous Era, when the area had a warm, rainy climate, complete with lush palm trees, leaves, and vines. Such rocks are generally only accessible at spots like Table Mountain, where the powerful forces that formed the topsy-turvy topography shoved them up to the surface. In the Denver metro area, fossils tended to appear most often during construction projects, Hagadorn says: Tyrannosaurus rex teeth or fossilized leaves sometimes turn up as workers carve out a basement or dig a well.

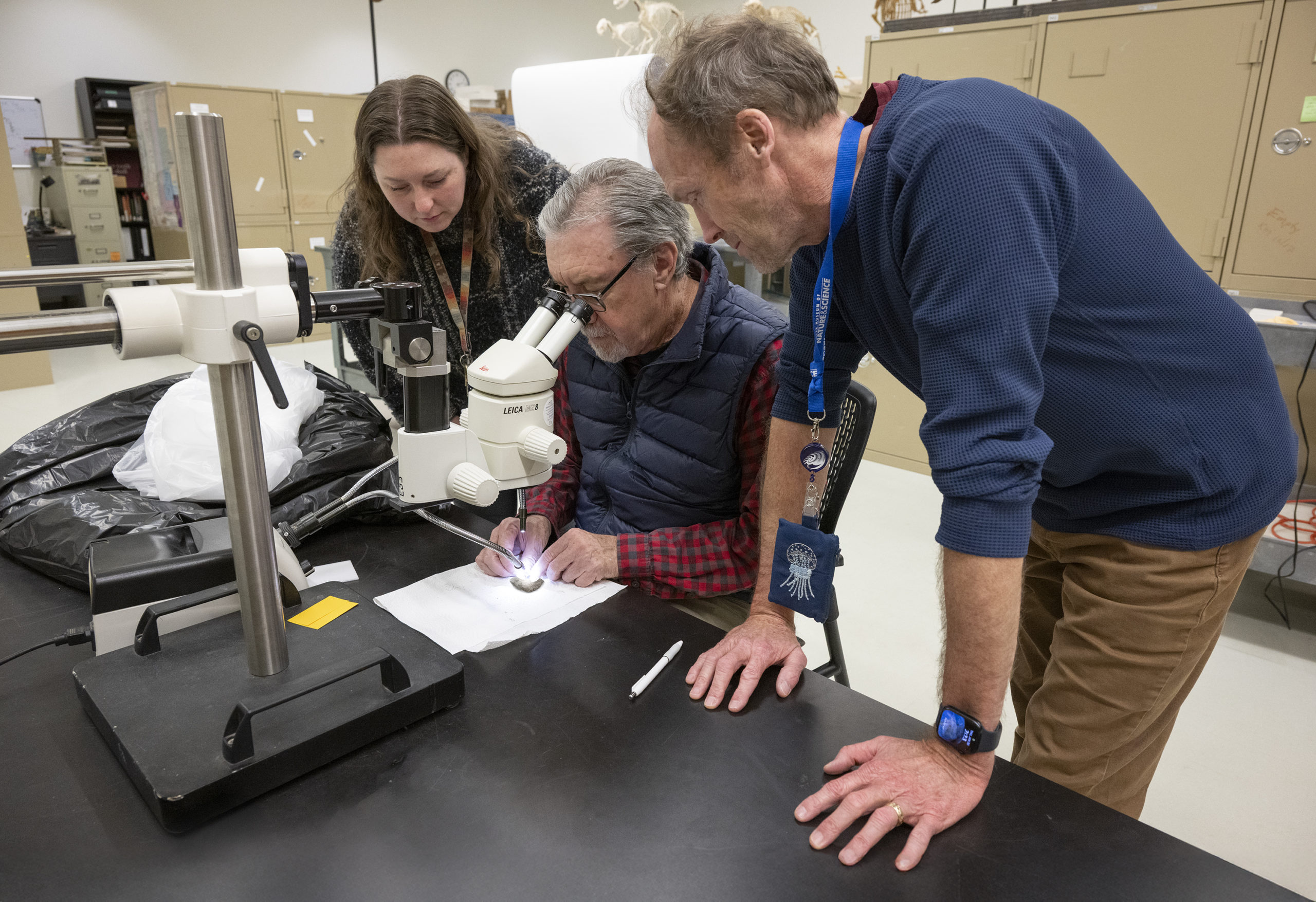

Or a test hole. In the spring of 2024, the museum began investigating the possibility of switching from natural gas to geothermal energy for its heating, air conditioning, and hot water. By January, two rigs sat in the museum parking lot, drilling test holes and gathering data about thermal properties hundreds of feet below ground. Rather than let an opportunity go to waste, the museum staff also took a core sample—a long, cylindrical tube of rock, containing different strata—to help understand the geology of the Denver basin. As they were cleaning the core, Hagadorn says, one of the museum’s geologists noticed a strange chip of stone with a spongy texture.

“He said, ‘That’s bone,’ ” Hagadorn recalls. “ ‘That could be a dinosaur.’ All of us practically ran out of the museum [to see it]. I’d never even heard of that happening.”

Read More: A Dinosaur Lover’s Guide to Colorado

The fossil was in bad shape. “When you drill a core, things that are brittle get twisted apart because it’s spinning,” Hagadorn says. It took careful work by a preparator who “spoke fluent dinosaur” to remove all of the pieces and jigsaw it together, allowing researchers to identify it as a vertebra from around the shoulder area of a dinosaur.

Pinning down an exact species identification is tougher. Hagadorn’s team believes the bone likely comes from one of two members of the larger family of ornithischian dinosaurs, a diverse group of largely plant-eating animals. One possibility is the extremely common Edmontosaurus, a “duck-billed” dinosaur that could max out at more than 40 feet long and was one of the most widespread large herbivores of its day.

Another is the smaller Thescelosaurus, a beaked, bipedal, fleet-footed plant-eater. But since the vertebrae of the broader family don’t differ much from each other, it’s hard to say for sure. And the museum isn’t likely to get any more from this particular specimen: In order to get down to the 763 feet required to reach the layer, “You’d need to excavate the parking lot and the rest of the space under the museum,” Hagadorn says. In other words, the juice isn’t really worth the squeeze. “Who’d want to dig up City Park?”

But, he notes, such fossils are probably more common than you’d think. Some kinds of dinosaurs, including Edmontosaurus and Triceratops, seem to have been as pervasive as modern deer, cows, or rabbits. While fossilization requires a tremendous amount of luck, the odds of a fossil surviving improve if it spends less time exposed to the elements on the surface, where everything from tree roots to wind, rain, and sun can wear it away into nothing. Protected from erosion by their overlying beds of silt and sand, Denver’s ancient remains have likely fared well. “I think the chances of finding another one would be pretty good [if anyone went looking under the city again],” Hagadorn says. “For all we know, there’s a Triceratops 500 feet underneath my neighbor’s house.”

Still, the chances of unwittingly sinking a test hole right into a dinosaur fossil are astronomically low. “There are hundreds of thousands of wells dug every year, and I’ve never heard of a report from any of them,” Hagadorn says. While it’s entirely possible that people just haven’t been looking for them—developers and construction workers don’t generally spend a lot of time checking drill cores for bones—only one other dinosaur fossil has ever been reported from such a sample nationwide, Hagadorn says. “We won the dinosaur lottery. We had no idea we had the winning ticket.”

Today, the fossil can be seen in the Discovering Teen Rex exhibition, alongside an adolescent T. rex found by a trio of boys in North Dakota. “If this had been cored on someone’s ranch and they had the subsurface rights, it might not belong to the people, but this one does,” Hagadorn says. “This core belongs to you.”