The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

On February 23, 1908, Leo Heinrichs was delivering early morning communion at Denver’s St. Elizabeth of Hungary Catholic Church when a man kneeling at the altar railing suddenly spat the host onto the ground and pulled a pistol from his pocket. “Watch out, Father!” an altar boy shouted. The man placed the weapon’s muzzle near the priest’s chest and fired a single shot. “My God! My God!” Heinrichs said before he collapsed. As men and women screamed, the dying priest attempted to scoop up the loose communion wafers that had spilled across the floor.

A 56-year-old shoemaker named Giuseppe Alia (initially Giuseppe Guarnacoto in at least one New York Times report, then Angelo Gabriele and Giuseppe Alio in other newspaper stories) waved the “smoking pistol above his head” as he rushed for an open door. On his way out, the Italian immigrant tripped and fell, then was captured by a parishioner near the church’s steps overlooking today’s Auraria Campus.

Alia didn’t know Father Heinrichs, the shooter later told police. “I just went over there because I have a grudge against all priests in general,” newspaper reports claimed Alia told a Denver police officer, the first of several conflicting narratives about Alia’s motive. “They are against the working man. I went to the communion rail because I could get a better shot…. I am an anarchist, and I am proud of it. I shot [Heinrichs], and my only regret is that I could not shoot the whole bunch of priests in the church.” Alia was taken to the Denver jail, where officials worried a mob might attempt to break in and lynch him.

Heinrichs—a 40-year-old German immigrant who’d arrived in Denver only five months earlier from New Jersey to take over duties at St. Elizabeth’s—was immediately celebrated as a martyr for his faith. The coroner who viewed the priest’s body discovered Heinrichs wrapped his arms and waist with leather straps studded with rows of iron hooks, perhaps as a form of penance. Friars who inspected Heinrichs’ room after his death found the priest slept on a wooden door. “His was a nature of that fine make, which we see only in God’s own men,” Eusebius Schlingmann, the senior assistant pastor of St. Elizabeth’s, wrote of the priest shortly after his death. “Gentle and affable to all, he knew how to be strong and forceful for good…. Here in the friary, we have lost a gentle master.”

Alia was transferred to Colorado Springs, where he awaited trial. He was convicted of murder, then sentenced to death despite the Catholic Church’s protests. Five months after the shooting, Alia was hanged in Cañon City. “Perhaps a more sensational and thrilling scene was never beheld by any of the 16 persons present than the execution of this misguided Italian murderer, whose cries and screams were only hushed by the automatic springing of the mechanism which forever silenced the tongue that cried for vengeance against those whom Alia had considered the destroyers of his home and happiness,” one news account reads. “Unfortunately, his neck was not broken, owing to the slipping of the rope, and he died of strangulation.” After 19 minutes, Alia’s body was cut down and he was pronounced dead.

Nearly two decades after his murder, Heinrichs was declared a “Servant of God” by the Catholic Church, the first step toward Catholic sainthood. Alia, meanwhile, became an ephemeral footnote—and an incomplete one at that. He was born in Sicily and was estranged from his wife and three children at the time of the shooting, newspaper reports say. Before arriving in Denver in November 1907, he’d spent time in Ellis, Kansas, and in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Alia told police he’d been unable to find work in Denver; his roommate in the city told investigators he had no idea Alia planned to kill a priest.

Anti-immigrant prejudice was mounting in the United States at the time of the shooting, as widespread fear of anarchism, socialism, and communism bolstered concerns of class warfare between the well-heeled business class and the wider labor movement rising across the country. The Socialist Party of America had existed for barely a decade by then, but it had seen its membership quadruple—to roughly 40,000—in that time. Similarly, the Industrial Workers of the World—a union that encouraged workers to “organize as a class, take possession of the earth and machinery of production and abolish the wage system”—started in 1905.

Reports of Alia’s confession immediately tied him to a wider movement, but there’s no evidence Alia was ever an anarchist, despite what newspapers reported at the time. “Most likely, we’re dealing with a confused man who randomly attacked a Denver priest,” says Phil Goodstein, a Denver historian who has studied Alia and Heinrichs and says Alia likely had an undiagnosed mental illness. “There’s nothing, anywhere, that points to a conspiracy or to any anarchist activity from Alia. Because of the way the story was told back then, I doubt we’ll ever know the truth.”

At the time of Heinrichs’ murder, the country had already begun an anti-anarchist fervor, a push that would continue for more than a decade and culminate with a World War I–era Red Scare. Within five weeks of Heinrichs’ murder, two other events were tied to alleged anarchists: an attempt to assassinate Chicago’s police chief and an aborted attempt to throw a bomb into a group of New York City police. In each case, neither was definitively linked to the group.

In the months before Alia’s execution, there were several conflicting reports about his motives: In one, he blamed the Catholic Church for the breakup of his marriage; in another, there were rumors he had a longstanding disagreement with Heinrichs in New Jersey, though there’s no indication Alia knew the priest or had spent time in that state. “[Alia] is a fanatic, but not an anarchist,” the labor organizer and anarcho-communist leader Lucy Parsons told reporters in 1908, adding that Alia was unknown within the anarchist community and likely had never participated. “The philosophy of anarchy has nothing in common with murder and assassination. We should not be held responsible for fanatics who say they are anarchists without being able to explain a single tenet of our philosophy.”

Alia’s attorney, Baron G. Tosti, argued his client needed psychiatric help. “I am somewhat a student of mental disorders…and I feel that Alia’s mind is not quite clear,” Tosti told the Rocky Mountain News nearly a week after the shooting.

None of that stopped law enforcement or Denver’s media at the time from turning Heinrichs’ murder into the lynchpin of a larger effort to drive out anarchists and labor activists nationwide. Alia’s arrest “might prove the key for which the authorities have been searching in their efforts to unlock the mysteries of the anarchistic organizations and lead to the final destructions of them all,” the Rocky Mountain News wrote just days after the shooting.

An early report attempted to link Alia to the Anti-Clerical Society—a group opposed to clergy for alleged influence in political and social affairs—though the accusation was later dropped. Then-Denver Police chief Michael Delaney told reporters that Alia’s “band” of anarchists included as many as 30 men originally “from stone quarries in southern Italy.” Each would soon be arrested, the chief said, but there’s no report that any arrests were made. In a headline titled “Exclude Low Immigrants the Remedy,” the Denver Post quoted a “prominent Italian who will not permit his name to be published” who said the best way to prevent similar crimes was “to end the immigration of low classes of foreigners.”

Authorities later claimed six men in New York and Pittsburgh were linked to Heinrichs’ murder. None of the six was tried for the crime, and a connection between those men and Alia was never established.

Alia’s crime—among other instances blamed on the anarchist movement—would be used as a cudgel to extinguish civil rights among scores of Americans. Activists were beaten and arrested by police, the federal government suppressed at least two anarchist newspapers, and a push was made to deport immigrant anarchists. Congress—in an attempt to ban anarchist literature—established political criteria for excluding material from the United States Postal Service.

“This was a time of accusations,” says former Colorado State historian Thomas Noel. “And Heinrichs’ murder helped play a role in it.”

Thousands of mourners attended the priest’s viewing at St. Elizabeth’s, a couple days after the shooting. Colorado Governor Henry Augustus Buchtel and Denver mayor Robert Speer attended the funeral, which included a 70-member choir. A procession began at Curtis and 10th streets downtown and ended at Union Station, where Heinrichs’ body left Denver on the 2:30 p.m. train that eventually took him to New Jersey for burial.

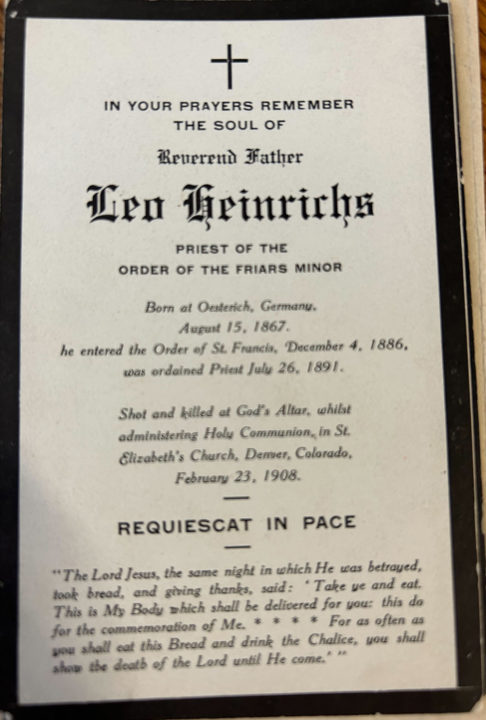

The effort for Heinrichs’ sainthood began almost immediately. “Well then, does his life tell us and his death convince us that he merits to dwell forever as a saint of the Church near the tabernacle where he stood an angelic sentinel and a pious minister?” the Denver Catholic Register wrote in 1916. Roughly 10 years later, St. Elizabeth’s printed prayer cards with Heinrichs’ photo. So many pilgrims began visiting Heinrichs’ grave at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery, in Totowa, New Jersey, that church officials had to move the coffin. Before reburying it, the casket was opened. “The body of Father Leo was not miraculously preserved as often happens with saints,” one Catholic newspaper noted at the time.

An ecclesiastical court gathered in Denver in 1927 to investigate the “proclamation of martyrdom,” though the case for Heinrichs’ cause for sainthood was later moved to New Jersey—where the priest served in at least two churches—and then was sent to Rome in 1932. The cause for Heinrichs’ beatification was authorized six years later. “The number of answers to prayer asking for Father Leo’s intercession in heaven, coupled with the extraordinary holiness of his life and the fact that he seemed to be providentially placed as celebrant of the Mass in which he met his death, all point to the success of the cause of canonization,” the Denver Catholic Register wrote.

Contemporary retellings of Heinrichs’ cause for sainthood generally regurgitate stories from nearly a century ago. In them, the case for Heinrichs has stalled without explanation, but there is hope for his ultimate canonization. Heinrichs’ story is made more interesting today when paired with Julia Greeley—a freed slave celebrated for her charity work and evangelism in Denver—whose investigation into canonization was opened by the Archdiocese of Denver in 2016. At the time of Heinrichs’ death, Greeley attended Sacred Heart Catholic Church, in Five Points. The idea of two Denver-based saints alive in the city at the same time—worshiping just two miles from each other—is irresistibly intriguing.

A dual canonization will never happen, though. In an email to 5280, the archdiocese wrote that Heinrichs’ cause for sainthood was terminated on August 13, 1940. “It turns out that the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith discovered a ‘grave impediment’ to [Heinrichs’] cause back then…according to the [Order of Friars Minor] Postulator General,” an archdiocese spokesperson wrote in the email. “This was likely some kind of moral issue, but we don’t know for certain, since the note ordering its suspension doesn’t specify.”

The archdiocese said it could not provide information about Heinrichs or the “grave impediment” that blocked the priest’s sainthood. Archdiocese spokeswoman Cynthia O’Neill wrote in an email that there “isn’t any additional information or a way to find out more.” The archdiocese referred questions to the postulator general of the Order of Friars Minor, who did not respond to a message seeking comment. A priest at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Catholic Church referred questions about Heinrichs’ life to a former priest from the congregation, who then passed along the queries to the archdiocese.

Little of Heinrichs’ time in Denver exists, beyond newspaper clippings. A small, four-page booklet—dated from about 1926—is held in the Denver Public Library’s archives (the Auraria Library also has a Heinrichs prayer card). The booklet includes a photo of Heinrichs and a prayer: “Lord Jesus,” it reads, “Who didst grant to the faithful son of St. Francis, Fr. Leo, the privilege of giving his life while distributing Thy Holy Eucharist; grant us also, by his merits and intercession, with the view to obtain his Beatification, the graces we now earnestly ask of Thee….” On the back page is the story of a rosebud taken from Heinrichs’ casket, which was said to be in “exquisite shape and delicate fragrance” years later and was responsible for “some remarkable cures alleged to have been wrought….”

One day late this past week, I went to see the prayer booklet, which is kept in a folder at the DPL’s Central Library downtown. The library’s archives said rose petals were included in the collection. When I opened the small folder, the folded, hand-size piece of paper was encased in a clear sleeve. The petals—like much of Heinrichs’ and Alia’s stories—had disappeared.