The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Coloradans are good at a great many things (making beer, staying fit, making more beer…), but sharing, it appears, is not among our talents. The Centennial State, owner of the nation’s 18th-largest economy, ranked a middling 34th in commodities exports in 2014 with $8.4 billion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That doesn’t seem to jibe with the state’s recent prosperity. Colorado tied Utah for the sixth fastest growing GDP the year before (2014’s data isn’t available yet), and our unemployment rate is well below the U.S. average.

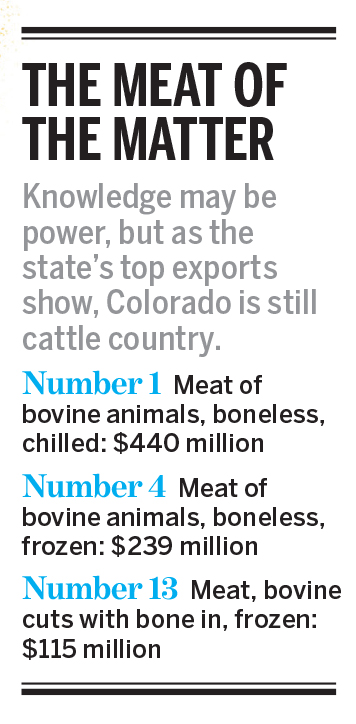

The paradox comes down to vocabulary. The Census Bureau defines a commodity as a physical good—a “thing” grown, mined, or mass-produced in the state. Colorado’s economy, though, tends to favor services, says James Markusen, a University of Colorado Boulder professor who specializes in trade. This includes fetching Coke refills, sure, but it also means law, architecture, and marketing. And while knowledge (such as the consulting Englewood’s CH2M Hill did on the Panama Canal expansion) is considered a service export as long as foreign money ends up in Colorado wallets, it’s harder to track—which might explain why the Census Bureau doesn’t break service down by state. Fortunately, the Brookings Institution does. The Washington, D.C., think tank’s most recent report on exports ranked Colorado 15th in service exports in 2012 with $11.4 billion. And Stephanie Dybsky of the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade (OEDIT) estimates that figure increased in 2013 and 2014.

To encourage such growth, OEDIT hopes to help companies whose exports barely register on the Census Bureau’s state rankings gain greater global exposure. Take, for instance, Flylow Gear. The Denver ski apparel company’s revenue has grown to $3 million, the vast majority coming from U.S. sales. Now it wants to expand in Europe because of the growth potential there. But Flylow makes most of its apparel overseas—if it sells more foreign-produced jackets in, say, Norway, the uptick won’t affect Colorado’s trade stats because they weren’t made here and state service exports (for example, the hours spent designing the jackets) aren’t disclosed. But it doesn’t matter how it’s counted: If Flylow’s European sales grow, it has to hire people in Denver to do things like coordinate orders. That’s why OEDIT used $20,000 from a federal grant program to help send Flylow and four other businesses to February’s Ispo Munich, the most influential outdoor recreation trade show in Europe. OEDIT also led companies to a health-care show in Dubai in January and plans to take more to an Australian mining expo in September. The idea is that although the state’s export numbers might not show it, new foreign markets (and customers) keep Colorado’s economy rolling. And there is vocabulary that reflects this thinking. Says Markusen: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”