The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

It started with a text.

Bob Stitt had been out of college football for the past half-decade, away from the career that defined much of his life. The former Colorado School of Mines head coach had already been fired from Montana and Texas State, two jobs he badly wanted but ones that made him reconsider every decision he’d made. The man who’d once sent defensive coordinators into therapy was back in Colorado, working a private-sector job and coaching high school ball as an assistant, a 61-year-old forced to accept that his shot at the big time evaporated years ago.

He’d been a cult hero. The mad scientist with a fast-paced offense, Stitt transformed the Division II Mines Orediggers from a doormat into a small-college powerhouse in the 2000s. Over 15 seasons, Stitt was twice named the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference’s coach of the year. He coached 16 All-Americans and had a Harlon Hill Trophy winner (D-II’s Heisman equivalent). Coaches from larger programs lined up to study Stitt’s work, to pick his brain on the jet sweep and the run-pass option. West Virginia’s head coach shouted out Stitt after an Orange Bowl win in 2012; offensive guru Mike Leach wanted a look at Mines’ playbook. ESPN once described Stitt as “your coach’s favorite coach.”

Those days now were a memory. Since leaving Mines for the top job at Montana in 2014, Stitt’s football life stalled. Montana fired him after just three seasons. He was dropped as the offensive coordinator at Texas State in 2019, after only one year into a five-year contract. Stitt’s confidence crumbled. He was bitter about how the door closed on his professional world.

As Stitt sat at home this past January, the college game in his rear-view, one of his former players texted. The Orediggers’ head coach, Pete Sterbick, was leaving the program. Stitt’s old job was suddenly available.

He thought about the opportunity that night, remembered game days in Golden, all those great games from his past. He’d left Mines as its all-time winningest coach and nearly brought the program its first football national title. He was in the school’s athletics hall of fame. Could he recreate that former magic? Would he even get the chance to try?

The next morning, Stitt called David Hansburg, Mines’ athletic director.

“I’d really like to come back,” the old coach began.

“I’m glad you called,” Hansburg said.

Read More: Colorado School of Mines Football Season Preview

Mines now finds itself addressing its football future by turning to its past.

Stitt was hired in February, a move school officials think will add stability to a program that’s been among D-II’s best but has seen three coaches depart in the past four years. Since Stitt’s successes between 2000 and 2014, the job in Golden had been treated as a stepping stone, a proving ground for coaches looking for the next gig. (Sterbick parlayed his 22-4 record at Mines into the offensive coordinator job at Football Championship Subdivision national runner-up Montana State.) If you could succeed with brainy engineering students focused more on grades than on football, the thinking went, what might you do elsewhere?

For years, Stitt deployed a fast-paced, pass-heavy offense that spread the field and stretched defenses. His teams regularly went for it on fourth down. In each of Stitt’s final six seasons at Mines, his unrelenting offense averaged at least 31 points per game. In his final season, Stitt’s offense averaged 89.9 plays per game, the highest of any team at any level within college football. Mines went 108-62 during Stitt’s run, which created outsize expectations for a school that had only 10 winning seasons between 1929 and 1999.

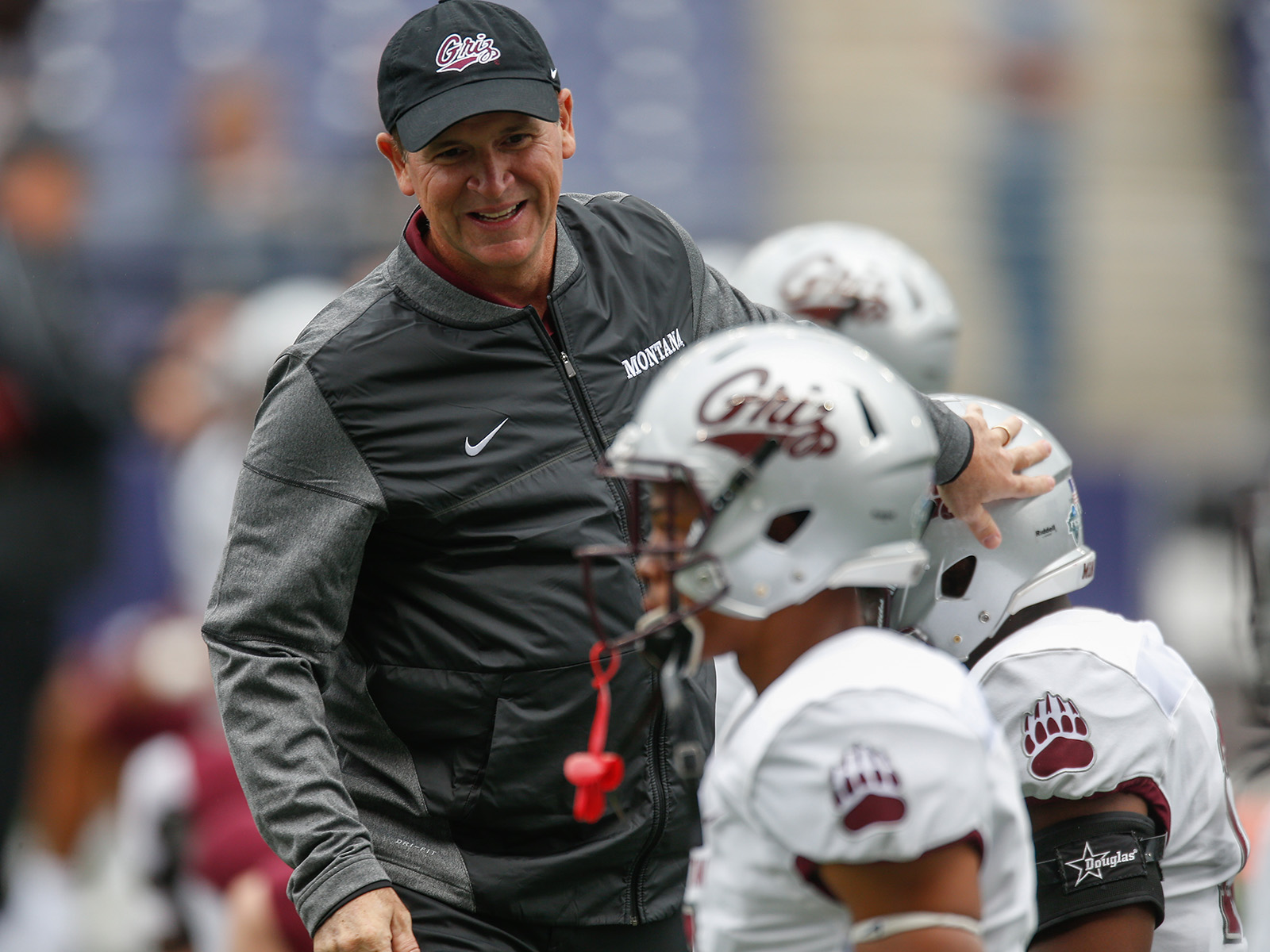

The wins at the time had Stitt thinking about even bigger jobs. “That’s human nature when you get into the business,” he says. “You win, you move. You lose, you move. Everybody’s always looking for that next step, and you really don’t ever enjoy where you’re at.” He was just 50, with an ascendant career. He left for Montana, where the Grizzlies are among the legacy programs within the FCS.

Things went sideways quickly. At Montana, Stitt went 21-14 and missed the playoffs twice in three seasons before getting fired. He quickly moved to Oklahoma State, where he briefly worked as an offensive analyst and everything seemed to be going backward. Away from his family, the coach shared a dorm room with a young assistant. He stared at the ceiling most nights. “‘How the heck did I get here?” Stitt asked himself.

He joined Texas State as its offensive coordinator in 2019, but was fired after just one season. The Bobcats’ offense finished 121st out of 130 Football Bowl Subdivision programs in points per game. Whatever remained of Stitt’s luster was gone. “You’re just like, ‘How can this happen again?’ ” Stitt says. “How can I be unemployed again?”

He came home to Colorado just before the COVID-19 pandemic. The unexpected stillness gave the coach something he’d rarely experienced: uninterrupted time with his family. He got to work and carved out an existence far from Saturday’s football sidelines. Stitt became vice president of AuctusIQ, a company that uses data to improve businesses’ sales performances. His youngest son, Sam, was in college at the University of Colorado Boulder and Stitt enjoyed the trips to campus. Stitt’s wife, Joan, cared for her elderly mother who lived nearby.

After more than three decades in the game, the coach realized he was out. Football seasons came and went. A few coaches called to gauge Stitt’s interest in jobs, but Stitt didn’t want to uproot his family. At any rate, he knew most athletic directors wouldn’t take a chance on a twice-fired guy heading into his 60s.

“It hurt because I knew in his soul that football was there,” says Scott Carey, a close friend of Stitt’s who is the co-offensive coordinator at Tarleton State University in Texas. “I know he came to peace with it, but you know there’s always that burning inside a true football coach.”

Stitt wouldn’t chase a comeback, at least not directly. Though he was still unhappy about how his previous jobs ended, he couldn’t entirely quit football. He created a room at home that he called his “lab.” Sitting alone, he’d study videos of his teams at Mines and Montana and Texas State. He’d watch how defenses played his teams. He’d devise schemes to counter defensive adjustments, see the subtle shift in a safety or a linebacker. Even if the snaps and passes and touchdowns were only in his mind, they were still his to create.

In 2024, the door opened—but just a crack. Stitt got a call from his friend Bret McGatlin, the then-head coach at Highlands Ranch’s Valor Christian High School. McGatlin needed an offensive coordinator. “I just saw an opportunity, and I’d love to have him,” McGatlin remembers of the conversation. “It was cool to see him kind of perk up and get excited by it.”

Stitt jumped at the chance, even if that meant restarting his football life at the bottom. “I told myself when I get the right opportunity, I will be ready,” he says. He immediately reengineered the Eagles’ offense. He got 16-year-olds to understand complicated schemes, saw promise in scrawny wide receivers navigating puberty.

Tucked away within high school football, Stitt felt the resentment from his coaching past recede. His team made the state playoffs with an offense that averaged 32.8 points per game. He stopped thinking about the next job and the one after that. He learned to enjoy what he had. “There was a joyful smile and laughter,” McGatlin says. “When you’re not coaching for a couple of years, you start to wonder if you can still do it. [Stitt] realized he’s still got it.”

Mines will always be a tough place to recruit. Applicants average 1394 on the SAT, which means Orediggers football coaches have a limited athlete pool. Even if a coach can bring in talent, few Mines players dream about NFL paychecks. There are job fairs and internships and loads of classwork. “You’ve got to want to coach here,” Hansburg, the athletic director, said. “It’s unlike any other place.”

Ten candidates interviewed for the head coach job. Stitt quickly emerged as the frontrunner. “He understands all the unique and quirky things about our student-athletes, about how the school works, about how to go recruit a kid that fits here,” Hansburg said. “The learning curve for Bob Stitt is way shorter than if I hired anyone else from the outside.”

Stitt, too, walked into a position he’d never imagined when he left the program 11 years earlier. The school that once made him beg for upgrades now has $21 million in stadium renovations. There’s also a 5,400-square-foot weight room.

That an academic school like Mines improved its football facilities is only one marker in the ways the college game has evolved on campuses nationwide. The run-pass-options, jet sweeps, slot fades, and other formations Stitt helped pioneer are in every playbook these days. The things that once made Stitt’s offense unique is standard among college football, which necessitates even more changes. Stitt says he’s tweaked his game plans, balanced his offense. His new version, he insists, is even better. Today, Stitt says he’s in “the best place I’ve ever been as an offensive coach.”

He admits he’s not the same person as he was during his first stint at Mines. “I’m just a lot more at ease now,” he said. “You’ve got to focus on the people that are working with you every day. I just want to have a good time coaching these kids.” After he was hired, Stitt spent an hour with each of his players. He talked ball and interests outside the game. Stitt says he spends more time listening to his players than he did that first time around, that he wants to understand what these young men want from the game and from their education.

“He’s been humbled a little bit,” Hansburg said.

Through three games, the results are mixed. Mines is 2-1. The team lost to conference foe Chadron State 34-28, its first loss to that program in more than a decade. The offense has shown flashes—572 yards against Washburn—but the defense has averaged 30.7 points against it per game.

Regardless of his path, Stitt doesn’t regret leaving Mines that first time. The coach learned about himself, mostly how he should appreciate what he has when he has it. He knows it will disappear again someday, which makes his return to Mines even more gratifying. “The things that happened that weren’t so great in my life allowed me to come back,” he says. “If you keep the faith, it will end up working out.”