The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Four-year-old Rachel Vlietstra takes a deep breath and reads aloud from her picture book. “Mom said, ‘Make your bed,’?” she says, and then glances at the illustration of a little boy in his messy bedroom. There’s a pause as she turns the page—but there’s no rustle of paper. In fact, there’s no physical book. Instead, Rachel’s mouse arrow hovers over a button on her computer screen. Click. “So I made my bed into a library and read and read and read.”

Rachel is perusing a digital book from an online library offered by Unite for Literacy (UFL), a Fort Collins–based organization whose goal is to create an “abundance of books”—a threshold that research has identified as more than 100 titles—in every Colorado child’s home. Recent studies suggest kids who have fewer than 100 books in their homes are more likely to struggle with academics and drop out of school before graduation. And as myriad studies have shown, dropouts have more trouble finding jobs and more health issues than their counterparts who’ve finished high school.

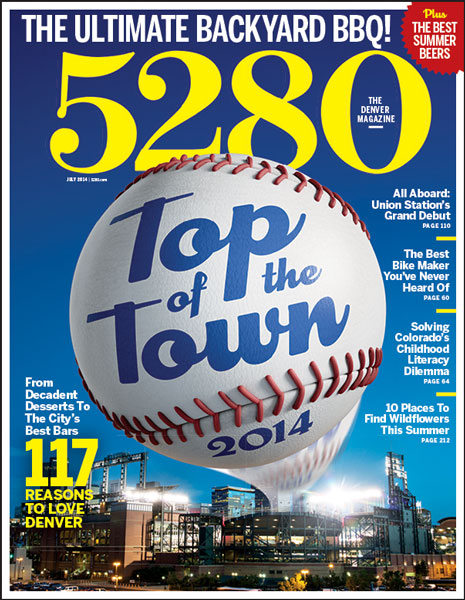

The situation here in Colorado is not encouraging: The 2013 Nation’s Report Card from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that six of 10 Colorado fourth-graders scored below proficient at reading. What’s more, six of 10 Colorado kids live in households with fewer than 100 books. UFL argues it’s no coincidence those two figures are identical. “What we’ve come to believe,” says Mike McGuffee, CEO of Unite for Literacy, “is that the fundamental root cause of illiteracy is a lack of relevant books in the home.”

This discouraging status quo prompted a statewide effort to bolster Colorado’s literacy scores with the 2012 launch of the Colorado Reads: Early Literacy Initiative and the passage of the Reading to Ensure Academic Development (READ) Act. But with the state’s rising poverty rate (more than 18 percent of children in Colorado live in poverty, up from 15 percent in 2008), the problem persists. The scary part? Colorado fares slightly better than the national average. “There’s a decline in the habit of reading in the United States,” McGuffee says. “We have a real opportunity to change that trend by focusing on children. And the very first problem we have to solve is access.”

Founded in 2012, Unite For Literacy debuted its digital picture-book library in August 2013 to keep up with the evolving way people, including parents, are consuming content. Anyone with an Internet connection, including a smartphone or tablet, can choose from UFL’s more than 100 free e-books, which, unlike other available e-book libraries, don’t require registration, downloading, or extensive searching through categories. The virtual books are designed to look like print versions with clean two-page spreads and vivid illustrations or photos for kids who haven’t started reading on their own yet.

But these books are anything but simple. One of the things Rachel’s mother, Sara Vlietstra, likes best about the books—in addition to having access to myriad options at any given time—is the audio narration, which is offered in up to 17 languages. (All of the text is in English.) The Fort Collins mother of three also has a kindergartner who’s learning Spanish and likes to listen to the Spanish narration while she reads so she can hear the pronunciation of the words. Conversely, English language learners, such as those from the growing Somali and Burmese populations in Northern Colorado—a region that contains more than half of the state’s migrant students—can choose to hear the story narrated in their native language while reading the text in English.

Part of UFL’s challenge is introducing the library to those who could most benefit from it. McGuffee hopes UFL’s sponsorship-based business model will help spread the word. Local businesses, organizations, and restaurants can sponsor a picture book that aligns with their mission and let customers know about the book by handing out bookmarks or menus printed with the URL, or by linking to the book on their social media platforms. The Bank of Colorado, for example, is sponsoring a book called This Is My Town; Whole Foods in Fort Collins has chosen What Colors Do You Eat? The negligible outlay to sponsor a book—it costs a business $600 to back one book for every child in Denver County—is meant to encourage participation from as many community companies as possible.

Although UFL is starting to garner national attention—last month, the program participated in the Early Childhood Education portion of the Clinton Global Initiative conference in Denver—the digitalization of children’s books is not without critics. Some argue students’ reading skills may suffer from the fragmented way children consume information on digital devices. Recent studies suggest the built-in distractions—animations, games, and audio features—of certain digital formats may contribute to reading comprehension problems. “We would advocate for an increased focus on strategies for e-reading in school reading instruction, so students understand how to transfer the strategies they use when reading conventional texts to their reading of e-books,” says Heather Ruetschlin Schugar, an associate professor at West Chester University and co-author of the aforementioned studies. “We’d love for parents to keep in mind that [digital] books with lots of pizzazz are not necessarily better.”

Others worry e-books are rendering the public library obsolete. But that’s not the case, says Jamie LaRue, the former director of Douglas County Libraries, who notes that there are more public libraries than McDonald’s franchises in the United States; two-thirds of Coloradans have library cards; and 30 to 40 percent of the items checked out of libraries are children’s picture books.

Of course, there’s the ever-present concern that the digital revolution is wiping out human-to-human contact, not the least of which includes those moments when Mom and Dad flip through a bedtime storybook with the kids before lights-out. If an e-book can narrate for the child, what happens to the parents’ role? Nothing, LaRue says. “It doesn’t mean you just park your child in front of a computer and walk away,” he adds. “The point is to engage your child around languages and stories. It’s not books versus technology. It’s books and technology.”