The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

When Derek Cianfrance was growing up in Lakewood in the 1980s, his family celebrated his brother’s birthday by renting a VCR and two movies: George A. Romero’s horror-comedy Creepshow and the slapstick sequel Airplane II. Cianfrance was so enamored by the experience, he rented the same VCR and movies for his birthday a few months later. His family got its own VCR later that year, and Cianfrance immediately recorded two films—Creepshow and Airplane II. He would invite a different friend to his house every day to watch them.

“I just couldn’t get enough of them,” Cianfrance says. “I loved watching movies over and over again, memorizing them, and seeing all the different things that were happening. I was a member of the VHS generation.”

This campy double-feature might strike you as an unlikely education for a “serious” auteur, yet that’s exactly what Cianfrance became. He’s directed three dramas—2010’s Blue Valentine, 2012’s The Place Beyond the Pines, and 2016’s The Light Between the Oceans—and all of them are best viewed with a box of Kleenex.

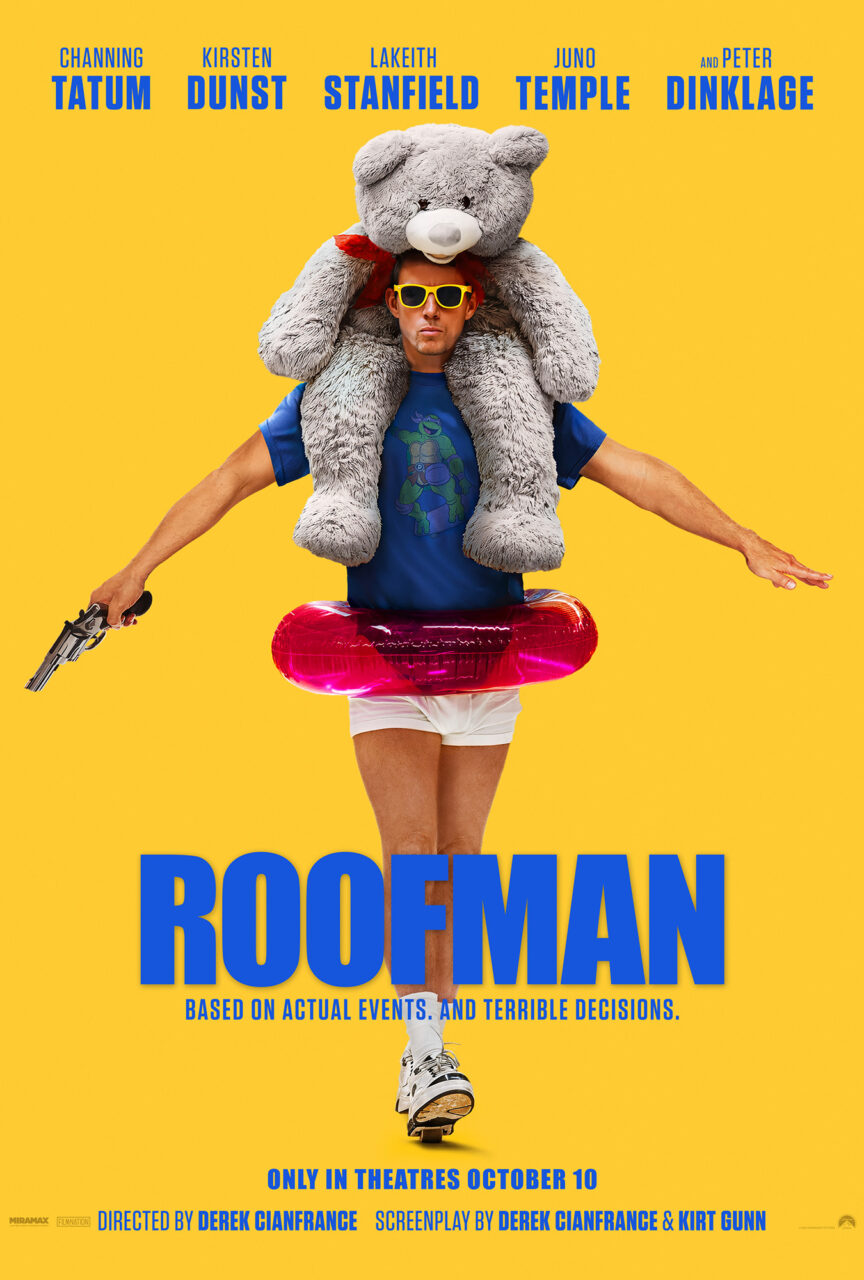

But his latest, Roofman, marks a hard turn toward his early VHS days. Starring Channing Tatum and Kirsten Dunst, the movie follows the sometimes slapstick exploits of Jeffrey Manchester, a real-life fugitive from prison who evaded authorities by hiding in a Toys R Us for six months. Ahead of the release of Roofman this Friday, Cianfrance spoke with 5280 about how his childhood in suburban Lakewood informed the film, learning his craft at the University of Colorado Boulder, and why, this time, he decided to look for laughs.

Editor’s note: The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

5280: Did you grow up making movies in Lakewood?

Derek Cianfrance: I remember my brother got a tape recorder for his birthday. I took it from him. I started using it to do skits. I’d blackmail him with it. Get my grandma to tell me a bad joke. Then the local librarian had a VHS camera that he used to lend me. When I was 13, I started making films. I was always the kid putting the camera in his family’s faces. They allowed me to annoy them and just accepted me being pushy and instigating. It was always my dream to be a filmmaker. I used to have a picture of Martin Scorsese above my bed. I’ve been very blessed in my life to do exactly what I was doing when I was 13 years old.

You studied under experimental filmmakers Stan Brakhage and Phil Solomon at CU Boulder. How did they influence you?

I had always dreamed of going to NYU or USC, but I ended up going to Boulder. Before then, I had never heard of experimental film; I saw movies in the theater. I remember the first movie I saw at CU was “Mothlight” by Stan Brakhage. [Editor’s note: Brakhage made “Mothlight” by collecting dead moth wings from light fixtures and pasting them, along with flower petals and blades of grass, onto film.] It just absolutely opened my eyes to a whole new possibility of film. Phil Solomon was one of the crucial mentors and most important people in my life. I was able to watch Phil and Stan live the lives of artists. They shopped at grocery stores, went to the same movies I did, put on their pants one leg at a time. But they were just committed to their art. I was like, ‘For these two people, film is part of their breathing.’

What attracted you to Roofman?

I felt like I had made a couple of movies that were heavy. I felt like people needed to be entertained and taken on a ride where I could hide the spinach in a movie a little bit. My producer Jamie Patricof had heard this story. I started talking to the real Jeff Manchester, who was in a maximum-security prison. He would call me. We’d have 15-minute conversations before he’d get cut off. His story was so unbelievable that I knew I had to talk to the other people in his life and make sure this is actually the way that it happened. That’s what I did. This movie was a way to bring me back to the movies I was making with my family when I was a kid.

When did Channing Tatum get involved?

I’d always been a fan of his since I saw him in A Guide To Recognizing Your Saints. He had this dancer’s body and this sense of movement. He looked like Gene Kelly and Marlon Brando. I thought, this is a vision of wounded, beautiful masculinity. I always wanted to work with him. He’s been a romantic lead, action star, done some of the most iconic comedy moments in the last 20 years, and he’s made autobiographical films like Magic Mike. I thought Channing could handle the multigenre story that Jeff had lived. Because Jeff, like me, was a kid of the VHS generation. He loved watching movies. My theory is that Jeff did all these crazy things and made these huge mistakes because he was the protagonist in his own movie in his mind.

How did growing up in suburban Denver help you make Roofman?

One of my big draws to this movie was its depiction of suburbia. I worked at the Walmart in Wheat Ridge. This is my upbringing. Whenever I go home to Colorado, that’s my world. I feel like that side of American culture is very rarely represented in an honest and truthful way. Oftentimes it’s treated as satire or a joke. I love the people who I grew up with. I love my home. I kind of related to Jeff because he also wanted so much to fit into that suburban culture. He wanted everything that was being sold. It became overwhelming for him because he couldn’t afford it. That’s why he made these bad choices.