The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Tucked in the northeastern corner of Afghanistan, the snowcapped Hindu Kush mountains rise steeply between the terraced fields of the Korengal and Shuryek valleys. It’s a beautiful but stark and inhospitable place: Tenacious farmers and goat herders battle scorching days and below-freezing nights as well as roving anti-coalition forces who take refuge in the unforgiving landscape. On the morning of June 28, 2005, high on one of those rocky slopes, 25-year-old Danny Dietz Jr. crouched shoulder to shoulder with three other Navy SEALs fending off an attack from at least 50 mujahedeen fighters.

The four men—Petty Officer Second Class Dietz, a gunner’s mate from Littleton; Petty Officer Second Class Marcus Luttrell, a hospital corpsman; Petty Officer Second Class Matthew Axelson, a sonar technician; and Lieutenant Michael Murphy, the team’s commanding officer—constituted the reconnaissance team for Operation Red Wings, a mission to locate and kill an insurgent named Ahmad Shah. After receiving reports that Shah was holed up near the 9,230-foot peak Sawtalo Sar, the four SEALs dropped in on the night of June 27 to confirm his location. Once they identified him, a force of Marine Scouts, Army Rangers, and Navy SEALs would move in to attack Shah and his men.

But early on June 28, three unarmed goat herders had discovered the recon team. Although they were likely Taliban sympathizers, they did not carry guns. The SEALs let the men go and retreated down the mountain to a more defensible position in the event the goat herders revealed the SEALs’ location to Shah’s men. Within two hours, they were attacked. Estimates place the number of insurgents at anywhere from 20 to 200. As the team’s communications specialist, Dietz worked the radio, but its signal struggled to penetrate Sawtalo Sar’s walls. The team was on its own. Machine gun bullets, AK-47 rounds, and the occasional rocket-propelled grenade screamed past, ricocheting and ripping into trees and boulders on the steep slope. Assessing the dire situation, Luttrell turned to Murphy, one of his closest friends, and said, “We’re gonna fucking die out here—if we’re not careful.”

From the day he was born at Aurora Community Hospital on January 26, 1980, Danny Dietz excelled at almost everything he did. He walked at nine months, he could swim at two years old, and when he was three, the toddler with a penchant for cowboy boots and Wranglers determined he would learn to ride a bike without training wheels. Hour after hour, his father, Dan Sr., pushed his son’s bike, watching him fall, dust himself off, get back on, and shout, “Again, Daddy! Push me again!”

That resolve came to define Dietz. At six, he ran himself into heat stroke to win Bishop Elementary School’s annual pumpkin race; the first-grader never stopped sprinting until the end, even though he’d already put a sizable gap between himself and the nearest finisher. Later, as a 19-year-old kid gutting out the Navy SEAL crucible known as Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL Training (BUD/S), he would set the record on the obstacle course—with a broken ankle. Behind that fierce determination, though, Dietz nurtured a softer side. He loved animals and made pets of everything from alley cats to lizards, once even keeping a butterfly in a jar and letting it out for “walks” around the house.

After his siblings were born, Dietz’s instinct to protect the things and people he loved became more pronounced: When his younger sister, Tiffany, fell through the ice at Little Dry Creek near their home, the nine-year-old stripped from the waist up, dove in and got her, then wrapped Tiffany in his jacket and carried her home. When his younger brother, Eric, was being bullied in elementary school, Dietz, an accomplished martial artist, confronted Eric’s tormenters. “He didn’t want to see someone getting picked on or bullied—it didn’t matter if he knew you or not,” Tiffany says. “He’d get into it, even if he got in trouble, because he thought it was the right thing to do.”

By the time Dietz was a freshman at Littleton High School, the sweet but stubborn kid who first aspired to be a cowboy and then a ninja had adopted a new identity: He became a rebel. Dietz traded his boots and hat for baggy jeans and tees. He started hanging out with kids who drank, smoked weed, and tagged buildings. The supremely fit gymnast and rock climber—who had always considered his body a temple—had little interest in drinking and smoking, but graffiti art appealed to him.

While his tagging buddies typically sprayed angular letters, Dietz, a talented artist, painted pictures of characters, alien creatures. The local police, not surprisingly, had little appreciation for his artwork and would chase Dietz, who went by the tagging name “Vandal.” He once narrowly avoided capture by hiding on top of a semi, and then, when a helicopter with a searchlight appeared, he slid under the vehicle, holding his 165-pound frame against the undercarriage. The police never did catch the wily teen. “He was fast,” Dan says. “God, he was fast.”

You can still find evidence of Dietz’s mischievous years near Littleton Cemetery. Just southeast of Arapahoe Community College, across the light-rail tracks, the graveyard affords one of the few panoramic views of the Front Range along busy South Prince Street. If you follow the road south to the beautifully crafted iron gates across from West Caley Avenue, on the cemetery’s second to last brick pillar you’ll find a faded, spray-painted gray “V” marring a rusted sign. That V, for Vandal, belongs to Dietz.

The afternoon of June 28, 2005, was a warm one in Littleton. It was a Tuesday, and Tiffany was shopping with her mother, Cindy. Independence Day was coming up. Her older brother, deployed overseas, was due for a visit in two weeks. They were waiting at the light at South Quebec Street and East County Line Road when Cindy’s phone rang. It was Patsy, Dietz’s wife, calling from Virginia Beach, where Dietz had been stationed since November 2001. As Tiffany put her Nissan into gear, she heard panic in her mother’s voice. A helicopter carrying SEALs had been shot down in Afghanistan. They knew that was where Dietz was, but little more. Tiffany’s hands shook as she gripped the steering wheel. She could barely push in the clutch as she turned the corner and headed home.

Dan, a former Navy medic, was already pacing on the front porch. He was still there an hour later when a blue Jeep parked in front of the house. Three military officials climbed out. Wearing his dress blues, Lieutenant Jon Schaffner explained that Dietz was missing in action. A Chinook MH-47 helicopter carrying eight SEALs and eight Army special operations aviators had been shot down in Afghanistan. Everyone aboard died. But Dietz—DJ to his close childhood friends and family—wasn’t on it. The chopper was on its way to rescue a four-man reconnaissance team that had called for help after being attacked by mujahedeen fighters. Dietz was one of the four SEALs on the ground. Nothing had been heard from the recon team since that call.

The next day the entire family flew to Virginia Beach to be with Patsy and await more news. They spent days in Dietz and Patsy’s three-bedroom home. Captain Robert Wilson made regular trips to the house to update the family. On July 2, word came that they’d found movement on the ground from a military tracking device. “At that point, all that was going through my mind was that we were going to be there for DJ’s homecoming,” Cindy says. “I just believed it was DJ. I thought back to the days when he was evading the police. I thought, That’s my boy, evading the Taliban.”

As a teenager, Dietz ran away from more than just the police. Cindy and Dan spent several difficult years tracking down their eldest after he’d once again snuck out of his bedroom or his classroom. “We’d drop him off at the front door of Littleton High School, and he’d go out the back,” Dan remembers. “He was bored.” (A gifted student, Dietz had registered as a genius on IQ tests.) Eventually, Dietz’s truancy became such a problem the courts threatened to take action if Cindy and Dan couldn’t control their son. In desperation, they enrolled him in a military-style school and residency program in Pueblo for a few months. Dietz loved it. He thrived under the intense physical and mental demands. By the time he finished, he had a goal: to become a Navy SEAL.

Dietz needed a high school diploma—not just a GED—to have a shot at getting into the country’s most elite fighting force. He’d already been kicked out of one high school and was woefully behind. So at 18, the skinny, strong-jawed teen with a gap between his two front teeth that would later earn him the nickname “550” (his SEAL teammates joked he could floss with 550 parachute cord) enrolled as a fifth-year senior at Heritage High School. Dietz maxed out his schedule, taking seven classes every semester; at night he plowed through correspondence class work to make up the missing credits. When he graduated in the spring of 1999, Dietz had completed nearly three years of high school in a single year. He’d also already enlisted in the Navy. He didn’t tell his parents. They found out when the recruiter called and asked why they hadn’t been present at Dietz’s swearing-in ceremony.

That summer, Dietz headed to basic training near Chicago, then BUD/S in Coronado, California. Less than 30 percent of the sailors who start BUD/S complete the grueling six-month program. On January 26, 2001, Dietz’s 21st birthday, he not only graduated BUD/S, but he was also ranked third in his class of 46.

By the time he joined Virginia Beach’s SEAL Delivery Vehicle Team 2—a SEAL team that specialized in undersea navigation and reconnaissance—Dietz had devoted himself to his career. At times he asked his young wife, Patsy, whom he married in 2003, to bring dinner to the base, along with their two beloved dogs, so they could eat as a family before he returned to cleaning and cataloging his gear. Dietz paid homage to his profession with a tattoo on his ribs and stomach of the Grim Reaper wrapped in an American flag; two more tattoos, one on the back of his neck and another on his shoulder and arm, honored his Apache ancestry. Although his grandfather was his closest connection to his Native American roots—he was part Apache—Dietz was extremely proud of his heritage. When he enlisted, he checked the box for American Indian/Alaska Native.

Upon learning he’d be deployed to Afghanistan, Dietz prepared rigorously: He logged hours in the team room making sure his gear was in order. He spent time with Patsy and the dogs. He called his family. The morning he left, April 16, 2005, Dietz told Patsy, who had served in the Navy for five years herself, “It’s only three months. It will go by quick. I am going out there to do something special for my country.” Before he left, though, Dietz made sure his will, his power of attorney, and his burial requests were all in order. According to his father-in-law, a fellow SEAL, Dietz was the only member of the Operation Red Wings recon team who did.

More than a week after Dietz disappeared, his family huddled in his house on July 4. It had been two days since they learned there was a survivor. While they waited for word from Afghanistan, the family was surrounded by Dietz’s touches. Every light fixture was one he’d picked out, wired, and installed. In the kitchen, he and Patsy had spent hours meticulously retiling the counters. As evening settled on Virginia Beach, the pop of fireworks echoed through the Dietz house. Again, Captain Wilson came to the door—except this time, he didn’t wear a uniform. He’d been off duty but wanted to tell the family himself: Dietz wasn’t coming home.

In the following weeks and months, the family learned more about what the Navy discovered after locating and rescuing the one man who did survive, Luttrell. Not long after the firefight between the four SEALs and Shah’s forces began, it became clear that the SEALs were outnumbered, out-positioned, and outgunned. Lieutenant Murphy told his men to fall back. They slid and crashed down Sawtalo Sar, severely injuring themselves along the way. Early in the fight, Dietz ran for an opening, hoping to gain a better position where his radio’s signal might get through. He made it and managed to call the base but was then shot in the right hand. The radio took rounds too, rendering it useless. As the team began another retreat, Dietz was shot again, this time in the shoulder. Then, minutes later, in the jaw. And then again. Luttrell, the team medic, had lost all of his gear in his tumble down the mountain; he could do nothing to help Dietz. By the time Murphy, badly hurt and bleeding from a stomach wound, walked into a clearing, and enemy fire, to use the satellite phone and call for help—an act that earned him the Medal of Honor posthumously—Dietz was already dead.

The autopsy report outlining Dietz’s wounds is five pages long. He was shot at least nine times, three times in the head and neck. His injuries were so traumatic that the Navy recommended a closed casket. You don’t want to remember him that way, they said. When Dietz’s family finally saw him, his body was wrapped in a shroud, his uniform laid on top. Through the fabric, Cindy could not see her son’s face; she could only pat his hands. Despite his injuries, Dietz—who joined the mission even though he was not a part of the same SEAL team as Luttrell, Axelson, and Murphy—never stopped fighting. He continued to fire and cover his teammates even after he could not stand or even speak. His actions earned him the Navy’s second highest honor for valor, the Navy Cross.

“He died too soon, but he did the thing he most wanted,” says Jordan Najera, Dietz’s high school girlfriend of four years. Years earlier, Dietz had confessed to her that when he died, he wanted to go saving people. In the letters and journal he kept for Najera while he was away at basic and BUD/S, in tidy handwriting often devoid of punctuation—a tumble of thoughts falling onto the page in his signature half-cursive print—Dietz alluded to his short life. “We found notes that he had written even before he went into the service saying that he wasn’t going to live for long,” his father says. “In some ways, it seemed like he was destined to do what he did.”

Early on Veterans Day this past year, Fort Logan National Cemetery in south Denver is almost empty. A dusting of snow kisses the frozen grass. The official Veterans Day ceremony doesn’t start until 11, and it’s been moved indoors because of the frigid temperatures. Inside the public information center, an elderly gentleman, a veteran, peers closely at the number on a scrap of paper: 6537-D. “Dietz?” he asks. “He gets a lot of visitors.”

Outside, he walks to the road and stops, pointing east up Logan Boulevard. “You can see it from here,” he says. “It’s the one with flowers.” Within a few steps of the parking lot, Dietz’s grave, one of more than 90,000 here, is easy to spot. It’s festooned with red, white, and blue blooms, some real, some fake; an autumnal arrangement in the shape of a cross juts above one side of Dietz’s marker. Only one other headstone in the area bears any evidence of visitors.

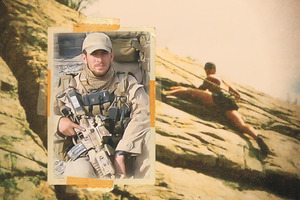

“It’s hard for me to go there,” Dan says of his son’s gravesite, “to realize that’s my little boy lying in that cold, hard ground. I like to go to the statue instead. I like to go see the people who go there.” The statue is an eight-foot-tall bronze likeness of Dietz in Berry Park, halfway between the Centennial Academy of Fine Arts and Goddard Middle School, which Dietz attended from 1992 to 1994. Cañon City sculptor Robert Henderson modeled the statue after one of the last photos taken of Dietz in Afghanistan: The SEAL is crouched, his left arm balanced on his knee, his right hand holding his rifle at parade rest.

The landmark is just one of the many reminders of Dietz’s legacy sprinkled throughout the metro area. On the second floor of the New Customs House at 19th and Stout streets, you’ll find Denver’s Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS), affectionately called “freedom’s front door.” Everyone from Wyoming and Colorado who has served in any branch of the military has passed through this facility. The swearing-in room is named in Dietz’s honor. Where West Mississippi Avenue and West Mineral Boulevard cross South Santa Fe Drive, signs designate the stretch of road as the “Navy SEAL Danny Dietz Memorial Highway.” The Texas Roadhouse Grill in Englewood houses a kind of Dietz mini museum in its waiting area. And near the student center at Heritage High School, a massive display case commemorates Dietz; a stone on the football field reads, “We appreciate our freedom. We play today to honor the heroes of Navy SEAL Team 10 and Operation Redwings.”

The Dietz family also honors the SEAL’s legacy through two organizations that bear his name. The Danny Dietz Memorial Fund is a scholarship for Heritage High School students. The Danny Dietz Leadership and Training Foundation works to help kids like Dietz through physical training, tutoring, and personalized counseling. Many of the young people who have been trained or sponsored by the foundation have gone on to their own military careers.

And, of course, Dietz has been memorialized in the book and film Lone Survivor, starring Mark Wahlberg as Marcus Luttrell and Emile Hirsch as Dietz. Both the book and the movie found enormous commercial success, thanks in part to the American public’s fascination with SEALs. Our captivation often overlooks one thing, though, says former SEAL David Rutherford, one of Dietz’s training instructors. “The idea that SEALs are this elite warrior class with a heartless personality—that you just point us in the direction and we kill everything out there—is wrong,” he says. “The real nature of a SEAL is an overwhelming commitment to serve the man next to him, and that’s all relative to our tremendous ability to love.”

(Read our Q&A with Emile Hirsch)

It’s in that spirit that, on January 26, 2015, the Dietz family gathers at Fort Logan with a few dozen friends and relatives to celebrate what would have been Dietz’s 35th birthday. It’s an unseasonably warm January day. Dressed in short sleeves, one of Dietz’s Native American cousins performs the sage ceremony. She blesses both Dietz’s marker and that of the man buried to the SEAL’s left, U.S. Army Special Forces Sergeant First Class Daniel A. Romero, who was killed in Afghanistan in 2002. There is no one on Dietz’s right. Little is said. After the ceremony, the crowd moves closer together. No attendant is more than 20 feet from Dietz’s marker, and most hold balloons. In a single moment, they let them go. As the pod of red, white, blue, and gold balloons swirls skyward, the sunlight glinting off their Mylar skins, Dietz’s two-year-old nephew, Carter, raises a chubby hand and points at the sky. “Uncle Danny flies,” he says. “Uncle Danny flies.”