The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

I can write this now, now that the sting has subsided and I hold the reward in my arms. The weight of our baby girl against my chest and the powdery smell of her skin has turned three turbulent years into whispers. My heart hums when I feel the grasp of her fingers. Her tiny head, capped with hair the color of shiny pennies, fits inside my cupped palm. She is a miracle, our miracle. We gave her a family name: Georgia.

We always knew we wanted to have two children—I just had no idea what it would take to arrive at a complete family. Our first child, Ella, was conceived easily. Although I didn’t enjoy the pregnancy—I never got used to having my swollen belly on display—I relished the reward. Ella grew quickly: It seemed like mere moments had passed as we transitioned from nighttime feedings to moving the baby swing and the ExerSaucer to the basement. We set up the high chair. We celebrated milestones: first words, the pincer grasp that delivered single peas to her mouth, the halting steps that foreshadowed walking. We pulled the high chair up to the dinner table and ate together. We were a family. Still, an empty chair seemed to wave at us from across the table. The equation was incomplete; there was room for one more child.

It was the second baby who gave us unexpected trouble and toppled our laissez-faire world. While we quietly struggled to overcome three miscarriages in one year, we had everyone—acquaintances, coworkers, grocery clerks—smile and ask us about number two, or, worse, recommend that we speed things along so that there wasn’t too much of an age gap. I choked down those well-meaning comments and my silent responses like bitter medicine.

It was the doubt—what if we can’t?—that became a paralyzing, emotional black hole. It hardened us. After the first miscarriage (surely a fluke, we thought), we had a positive pregnancy test, and yet we couldn’t—we wouldn’t—let ourselves begin the dreaming, the wonderment of who that little being might become. After the second loss, and then the third, any semblance of excitement was soaked in dread. Was there a heartbeat? For how long would it beat?

We had some answers, but those too were fraught with sorrow. Tissue testing concluded that the first two fetuses, a male and then a female, had chromosomal abnormalities “inconsistent with life.” The results were inconclusive with the third pregnancy (another female), but we assumed the same. It was frightening that our respective cells could combine to create such severe aberrations. We had our blood tested and our DNA unraveled. No deviations. Again and again we asked the questions “Why?” and “How?” There were no answers onto which to hang our distress. Instead, I was deemed a “habitual aborter,” a searing and obtuse medical term. The black hole widened and swallowed us. Could we bear another attempt and endure another loss?

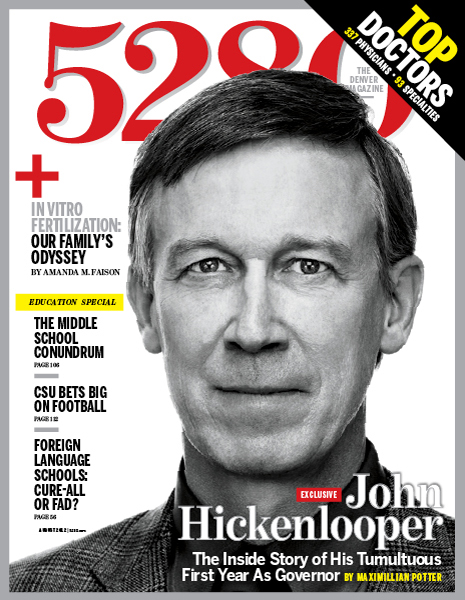

5280.com Exclusive: Watch a Q&A with the author.

Behind the Scenes at 5280: A Q&A with the Author of A Place at the Table from 5280 magazine on Vimeo.

.

I am not an anomaly. One in six couples is infertile, and my experience—the in vitro fertilization experience—is becoming increasingly common. I am one of the growing number of women who has had a specialist on speed dial. I’m one of thousands each year who, when passing through airport security, has had a doctor’s note explaining the pouch of syringes and liquid hormones packed deep in her luggage. At a dinner party a couple of years ago, six of the 10 couples seated at the table were undergoing fertility treatments; we just didn’t know it at the time. Today, I have more friends and acquaintances who have sought fertility help than not.

I recently attended a meeting at my older daughter’s elementary school. In that room of 20 parents, three had twins. In nature, the chances of having fraternal twins is one in 60; identical twins is one in 250. The influx of multiples shouldn’t be possible. But since 1980 there’s been a 74 percent increase in the number of twin births in the United States. This is the result of two things: an increase in reproductive technology like in vitro fertilization, and, in our modern world, a surge of women waiting longer to begin a family. Women older than 30 have a higher chance of conceiving twins. I was 33 when Ella was born.

The New York Times reports that in this country, some 58,000 babies—not all of them twins, of course—are born of in vitro fertilization each year. Around the world there are an estimated four million IVF babies alive today. Our daughter Georgia is one of those children. The first published case of a “test-tube baby” was in 1974 (coincidentally the year I was born), but the first confirmed case was Louise Brown, who was born in England four years later.

Fertility treatments have changed dramatically over the years. In the 1970s, they consisted of a lot of guesswork. Today, there’s a fertility industry with multiple entry points. The least invasive option: popping a couple of courses of the ovulation stimulant Clomid (about $100 for a month’s supply). Twenty-five percent of women will get pregnant within a three- or four-month cycle on the drug—which is slightly lower than the normal rate of conception in fertile couples. There’s also intrauterine insemination (IUI, though commonly called artificial insemination), in which sperm are deposited into the uterus via a small tube. IUI’s success rate runs 35 percent when used with a drug like Clomid. The cost is comparatively affordable at $600 to $800 per attempt.

The most effective procedure, however—and, at an average of $15,000 to $20,000 per round, the most expensive—is in vitro fertilization. It’s also the most invasive. Injectable hormones force the ovaries to (hopefully) produce an abundance of eggs, which are captured, fertilized with sperm, and grown in Petri dishes. After several days, any surviving embryos are assessed for vitality and either transferred to the uterus (usually one or two at a time) or frozen for future use. There are multiple variables, such as the quality of eggs and a woman’s age, but success rates for women in their mid-30s come in around 35 to 40 percent.

At Denver’s Colorado Center for Reproductive Medicine—one of the world’s most respected fertility clinics—the IVF success rates are substantially higher at 67 percent. CCRM sees 250 to 300 new patients from all over the globe each month. Starting in January 2010, that new-patient list included my husband, Heath, and me.

Our oldest daughter, we now know, really shouldn’t have been able to be born. And yet she arrived just as planned. Heath and I were married in August of 2005, and Ella, all seven pounds, 14 ounces of her, was born in time for Mother’s Day in 2007. My pregnancy was effortless: I didn’t even know I was pregnant until I was nearly three months along. I was never sick. My only craving: fresh oranges. My only aversion: peppermint. We traveled to Italy for a babymoon, and up until nine months I continued my 6 a.m. workouts most days of the week. Two days before my due date, I baked and frosted 60 vanilla cupcakes for a friend.

Two days past my due date—and after 30 hours of labor and marginal progress—I was too exhausted to continue. Ella, who is named after Heath’s great-grandmother, came into this world by Cesarean section. Following the first gauzy moments of relief and elation, my doctor informed us that Ella’s head had been stuck in the birth canal. Without modern medical techniques, one of us, if not both of us, would have died during childbirth. Looking back, I’m quite sure the underlying lesson—you can’t plan everything—was lost in the haze.

Several days later, we strapped our baby girl into her car seat and headed home. We nestled her into the carefully planned nursery. Drawers held tiny folded clothes and freshly washed blankets. Her changing station was stocked with diapers, wipes, and tubes of Desitin. We checked and rechecked the baby monitor. We were scared out of our minds.

Our introduction to the world of parenting was, all considering, a smooth one. Ella was an easy baby. She ate well, slept well, and was generally smiley and even-tempered. Heath and I would sit in the backyard and marvel while Ella babbled and explored the world. We were doing it.

Shortly after we blew out the candle on Ella’s first birthday cake, we began to feel the tug of expansion. Heath is the youngest of three boys, all spaced about two years apart. I’m the eldest of two girls by nearly six years. We hoped to have our children close in age. We wanted them to grow up together, to be buddies and playmates, and to ultimately support each other as they moved into adulthood. That summer we began trying for baby number two.

By October, I was expecting. We were overjoyed; everything was going according to plan. Even so, I was caught up in the frivolity of the things I couldn’t have: wine, rare meat, sushi, Gorgonzola. Hot yoga and running were also out, as was ski season. I knew the sacrifices were short-lived and worthwhile, but they annoyed me. We traveled to Mexico, and I sipped virgin piña coladas, stayed in the shade, and attempted to suck in my stomach while I still could. The day before we left for home, I discovered prune-colored blood in my bikini bottom. I remember gasping.

I called Dr. Cristee Offerdahl, my gynecologist of 13 years, the moment we got back to the United States. She worked me in and did an ultrasound. On the monitor, in the middle of the gray mass, we could see the spastic flutter of a heartbeat. Our immediate relief was tempered by the news that the baby was measuring six weeks instead of eight, and that the heartbeat was slower than normal. I scheduled a follow-up appointment. Heath and I walked to the elevator squeezing the blood out of each other’s hands.

We tried to remain hopeful, buoyant even. My calendar could be off by a couple of weeks. The baby could be growing slowly, which would be concerning but not necessarily dire. But an ultrasound a week later confirmed what we already suspected: There was no growth; the fluttering heart had lost its fight. It’s a cold, sickening moment to realize that you’ve lost a baby—that you are suddenly a statistic. You are the one in three. I felt guilty for finding annoyance in the small sacrifices that come with pregnancy. I couldn’t help but think about the being—the size of a pebble, with emerging hands and feet—withering and dying inside of me.

There are two options after miscarriage: allow the body to expel the fetal material or have it surgically removed through a procedure called dilation and curettage (most commonly referred to as a “D and C”). We elected for the latter, and the next morning we arrived at an outpatient clinic at 5:30 a.m. Before I was wheeled into an operating room, Dr. Offerdahl gave both Heath and me hugs. Her blue scrubs felt soft against my face.

When I awoke an hour later, a nurse handed me a graham cracker and a paper cup of ginger ale. Heath was there. He explained that all had gone well but that Dr. Offerdahl said there had been an unexpectedly large amount of tissue. My eyes were still wet when a nurse wheeled me out to the car.

When I got pregnant again in February, we reigned in our excitement. We felt vulnerable, and it seemed safer not to fully embrace the pregnancy’s potential. At seven weeks, I miscarried. We never saw a heartbeat. Just days before my 35th birthday, I blinked back tears and lay on a gurney, again destined for the operating room.

The procedure went much the same as the first. The only difference was that this time, when signing the medical forms, I checked the box authorizing chromosomal testing. We hadn’t done this after the first miscarriage because it felt unnecessary and somewhat gruesome to have a scientist pick through cells to determine a cause. We were comfortable not knowing the answer. But, as it turned out, the first fetus had required further testing anyway: Severely enlarged, grapelike cells indicated that it had been a “molar pregnancy,” in which a fast-growing mass overtakes the fetus and extinguishes it like cancer. A series of blood tests cleared me of cancerous cells, but the implications rattled us.

Though we couldn’t have known it at the time, that extra testing was a blessing. Over the phone, we learned the first fetus had three copies of chromosome 22 instead of two. After the second miscarriage, I got a similar call: The second fetus had three copies of chromosome 6. Both anomalies were death sentences.

Dr. Offerdahl suggested we seek help from a fertility specialist. I wasn’t ready. I was bullheaded enough to think our next attempt would yield a healthy baby. How could this possibly happen for a third time? And yet, almost one year after our first miscarriage, I lost a third pregnancy. This time, there was a quivering heartbeat—we could see it on the high-definition screen—but there was little measurable growth. My face crumpled. I asked the ultrasound tech to check again. I turned my head away.

Instead of leaving through the waiting room, Dr. Offerdahl let us seek solace in her office. I gripped a ball of tissue in one palm and Heath’s hand in the other. I’m sure my sobs could be heard through the door. The sun was shining outside the window, but the world felt dark and hollow. Why, when so many children are born to those who don’t want them, couldn’t we bear a child whom we would cherish? We left the office with yet another D and C scheduled and a piece of paper scrawled with a phone number for Dr. Debra Minjarez at CCRM. We got home and held Ella tightly. I tried to explain away my tears.

In January 2010, two months after the third miscarriage, we entered Dr. Minjarez’s office for the first time and took seats in the russet-colored leather chairs. The possibility that we might not be able to have a second child was becoming very real. Would a time come when a family of three felt complete? We were blessed to already have a healthy, thriving daughter, but when friends and family reminded us of that fact, it made me angry that Ella was somehow considered a consolation prize.

I dreaded the inevitable question: Would we consider adoption? Though a perfectly reasonable query, it felt both extreme and shallow to have to answer. It wasn’t that we were opposed to adoption—not in the least. It’s that, somewhere inside of us, there was still hope that we could right our toppled world. We needed to exhaust all of the medical options before exploring alternatives.

We explained our situation to Dr. Minjarez, who took notes as we spoke. She had a wide, welcoming smile, and her demeanor was easy and empathetic. We liked her immediately. Our story, very simply, was this: We were fertile, and I could sustain a pregnancy. Our breakdown lay deep within our genetics. What we needed was the assurance of a healthy embryo.

That last detail was critical—and it was our reason for choosing CCRM. The clinic, founded in 1987 by Dr. William Schoolcraft, pioneered the technology of preimplantation genetic screening (PGS), in which embryos’ chromosomes are counted and evaluated. (The correct number of chromosomes is 46, or 23 pairs derived from the male and female, respectively.) Whereas most couples seek in vitro fertilization solely to improve their chances of having a viable pregnancy, we required the next step: We needed IVF to create embryos so they could be grown in Petri dishes and their chromosomes could be evaluated. PGS technology isn’t perfect, but the 90 percent accuracy rate beat our natural chances of conceiving a healthy baby.

We underwent physicals and were poked and prodded. During the exams, Dr. Minjarez discovered I had a wall of tissue, either a natural septum or an accumulation of scar tissue (possibly from the multiple D and Cs), that closed off part of the uterine cavity. It had to be surgically removed. We learned this information in late February, just as we finished signing the IVF and genetic screening consent forms—50-plus pages outlining the risks, the procedures, the protocols, and, ultimately, our assumption of responsibility. It was more intimidating than buying a house.

Given that IVF is an elective treatment (no one needs to get pregnant like they might need, say, open-heart surgery), insurance coverage is nominal. I switched from United Healthcare to Heath’s insurance (Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield) in hopes of a more progressive plan. In the end, with the three miscarriages, we incurred close to $35,000 in medical expenses. For the roughly $30,000 we spent on IVF and the corresponding drugs and procedures, we received two reimbursement checks. Both were for $40.

On March 14 at 8 p.m., Heath and I stood in our kitchen with an alcohol swab, a glass vial of Lupron, and a syringe. Ella was asleep upstairs. This was the first of 45 injections in 23 days. Several days earlier, we’d spent four-and-a-half hours at the clinic learning, among other things, how to give the injections. My stomach had been in knots ever since. On our nurse’s recommendation, we practiced on an orange.

Now it was time. I pulled up my shirt, pinched my abdomen, and squeezed my eyes shut. The hormone felt cold under my skin. When Heath removed the needle, a bead of ruby-red blood stood on my skin. The used syringe rattled when we dropped it into our red plastic “sharps” container. Eventually the plastic box would be so full I’d have to ask a nurse for a new one. I drew a fat X through Day 1 on the calendar.

On the morning of April 6, 2010, after blood work and an ultrasound, the nurse used a black Bic pen to draw a circle—a target—on my right hip. Heath was instructed to administer the “trigger shot” at 9 p.m. This injection was different from the ones over the previous weeks: Not only was it intramuscular rather than subcutaneous, but the blast of hormones would tell the eggs to mature and release. The time had come. My chest tightened with relief, excitement, and terror.

That night we watched the instructional video several times, re-read the literature, and laid everything—the syringe, the vial, the alcohol swab, the Band-Aid—out on the kitchen counter. I couldn’t sit still, but I forced myself to ice the circle to deaden any feeling. The TV babbled as Heath stuck me with the needle. A couple of seconds and it was over. Considering the weight of the moment, it was astoundingly anticlimactic.

Thirty-five hours later, I was wheeled into the operating room for “egg retrieval.” The anesthesia and the shake of the gurney made me feel carsick. I tried to breathe as Dr. Minjarez gently strapped my legs into what felt like ski boots. She talked to me until I drifted off to sleep. When I awoke, the embryologist relayed the excellent news: We had 20 eggs—five more than we thought possible. As soon as the April sunshine hit my face, I called my mom. Heath called his. For the first time in many months, our laughter was robust and genuine.

The next day, we learned that 16 of the eggs fertilized successfully. Even the embryologist seemed pleased. My mood lifted, despite being so sore that I couldn’t get in and out of bed on my own. Within 24 hours, we got another call: Ten embryos were progressing. From 20 chances to 10 in two day’s time; it was a pointed lesson in survival of the fittest. I’m not especially religious but I turned my head skyward, thankful we had so many miracles.

Six days after the egg retrieval, a female voice on the other end of the phone told me that nine embryos had made it to blastocyst, an important stage defined by cell differentiation. Our individual, blossoming embryos were no longer just clusters of embryonic stem cells—they had successfully divided into placental and fetal cells. All nine embryos were biopsied and frozen. Those cells were shipped to a New Jersey lab for chromosomal screening. We would have results within six weeks. The time would be spent recovering from the hormones and undergoing surgery to remove the partition in my uterus.

On May 19, Dr. Minjarez left me a voicemail: “The results are back and we’ve got six healthy embryos! I couldn’t have hoped for anything better.” A few weeks later, we went over the findings in person: Of the six healthy embryos, two were considered “AA,” or excellent quality. Of the three abnormal embryos, one had two extra chromosomes; another had Turner Syndrome (a mutation that occurs in one of every 2,500 girls); and one wouldn’t reveal its genetic code. The aberrations were as haunting as ever—and confirmation that we made the right decision to pursue both IVF and preimplantation genetic screening.

Five months after our first appointment with Dr. Minjarez—and more than two years since our first miscarriage—we began to plan our embryo transfer, and hopefully a corresponding pregnancy. Outside of choosing to implant one or two embryos (we decided on one), we had no say in which one would be selected. Dr. Minjarez would make that decision. A date was set: July 29, 2010.

Another $600 worth of drugs arrived via FedEx. I was on a first-name basis with our deliveryman after the monthly, and sometimes weekly, deliveries. I opened the box and had to sit down: vials of Lupron mixed with syringes, estrogen patches (that would leave sticky outlines on my abdomen for months), and progesterone inserts. I told myself it couldn’t be as bad as the ramp up to the trigger shot. It just couldn’t be.

In the meantime, Heath began a master’s degree program at the University of Colorado, and I went on vacation. I played with Ella. I injected myself with Lupron. I wore a tank top over my bathing suit so no one could see the estrogen patches. Heath and I tried not to fixate on the date, July 29. The journey, as arduous as it had been, was far from over. Everything had to go perfectly for me to not only get pregnant, but also to keep the pregnancy.

The day finally arrived. On the drive to the clinic, we communicated by squeezing our interlaced fingers. It will work. It will work. It will work. The mantra was like a heartbeat.

There was blood work and then a wait that stretched forever. I attempted to read. A nurse came in and secured me to the bed. Before she left, she switched on a screen. There, illuminated by light and magnified by a microscope, was embryo number seven. We stared at it in reverence. We searched it for life. That unremarkable gray mass was the most extraordinary image we’d ever seen. It’s what we had been working toward. It might be our future child. Heath took a picture.

The transfer was short but difficult. I cried the whole time. The bed was tilted so violently backward that the blood gathered in my head. My ears filled with the thump of my heart. It took two tries before Dr. Surrey—Dr. Minjarez’s counterpart—sent Lucky Number Seven on its way. The doctor whispered “All aboard” before wishing us luck and leaving the room.

The 48-hour mandatory bed rest was nothing compared to the nine interminable days that had to pass before I went in for a pregnancy test. Then, when the nurse did call, it seemed to take her forever to deliver the news. Finally, she said: “Congratulations, you’re pregnant.” I shrieked and jumped off the couch.

For 11-and-a-half weeks, I was so nauseated I could only nibble plain, untoasted bagels. Peaches were my nemesis. I was light-headed, tired, miserable. But I was relieved to have the physical, tangible proof of the life growing inside. It took us a long time to lose our nervous edge. At eight weeks—a week longer than the previous three pregnancies lasted—we exhaled. At the all-important, three-month mark, our shoulders softened. By six months, Dr. Offerdahl gently encouraged us to put aside our lingering fears. We moved Ella to her new room. We set up the crib in the nursery. But even with the reassurance of ultrasounds, I knew our apprehension wouldn’t dissipate until we held this baby in our arms. Everyone thought it was a boy—everyone except Ella.

This time, we didn’t take any chances; I was scheduled for a 7 a.m. C-section on a Monday in mid-April. Dr. Offerdahl was waiting for us in the operating room. Her surgical mask couldn’t hide her smile. Those last moments as expecting parents were fraught with emotion. There was clarity and finality—something we had chased for years. I was looking up into Heath’s face when Dr. Offerdahl held our baby in the air. And then: the long-awaited newborn cry. We held her, named her, and soaked up her presence.

Time is a gift. It has softened the edges of our torment, even blurred the pain to the point of forgetfulness. I don’t want to forget. I want Georgia to know how hard we fought for her. I want Ella to know that when she took us by the knees and pleaded with us to give her a brother or sister that we were listening—and desperately trying. I never want to forget our miracle.

We have more miracles, of course. There are five more waiting in a freezer. What to do with the embryos haunts us. We viscerally understand the potential in those cell clusters. There’s a universe waiting in each. But our family is complete. We will hold onto them for awhile, but when the time comes, we’ll donate our embryos to research. It’s science that got us here—that granted us the ever-expanding life that is Georgia—and we want to further that science for someone else.

Watching Ella hold her sister for the first time caught me at the throat. The image was framed by relief, pride, and euphoria. But the first time I truly grasped our new family dynamic was six days after Georgia was born. It was dinnertime and Ella, who was a month shy of turning four, bounced to the dinner table. She stopped short of sitting down and wheeled around. “Where’s Georgia’s seat?” she asked. “I want to sit next to Georgia.” Ella’s request twinkled through the air with a bell-like ring. It sounded bright and clear—and complete.