The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Steep and Deep

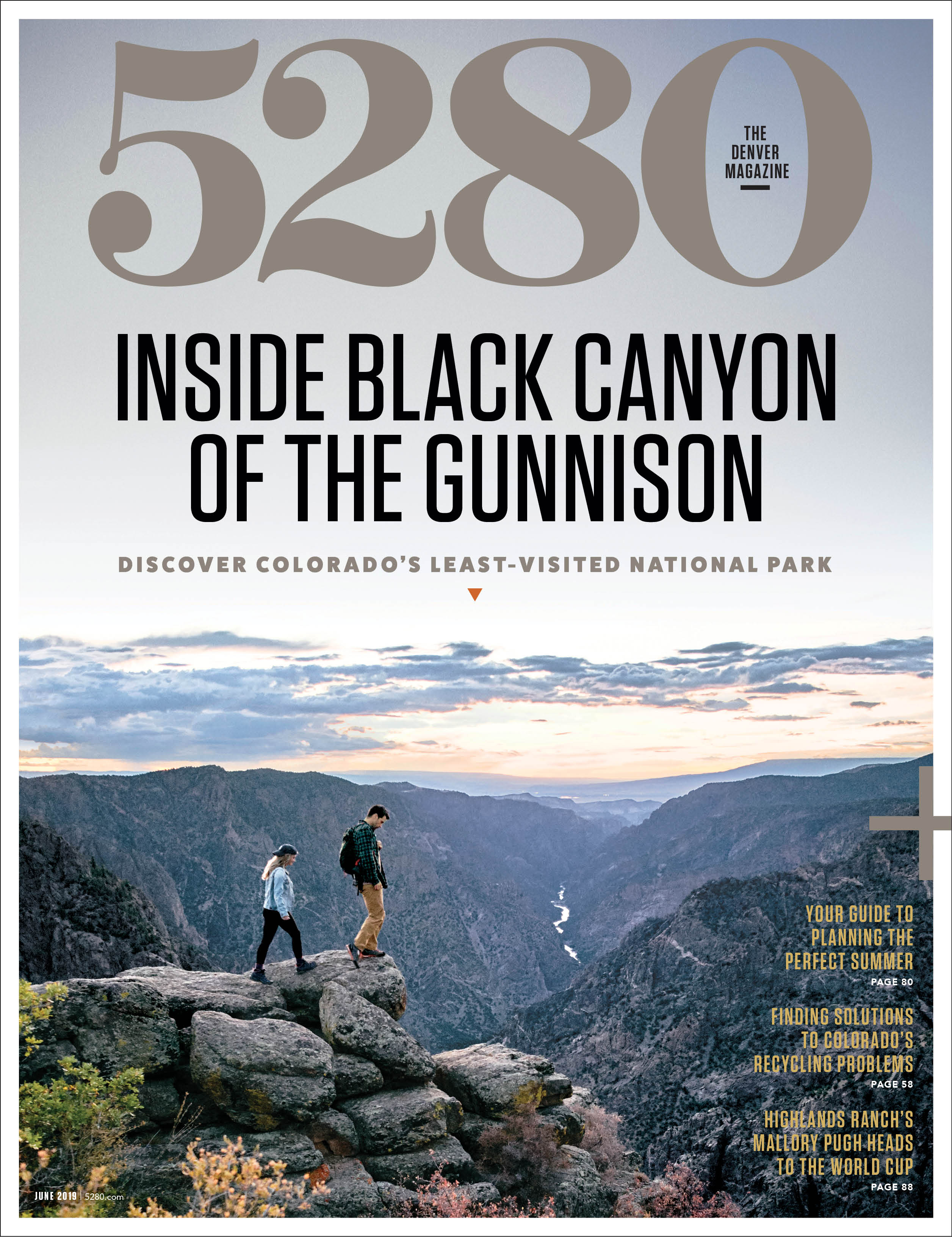

Gravity’s pull seems more powerful standing along the rim of Colorado’s Black Canyon of the Gunnison. Maybe it’s the 2,000-plus feet of nothingness, tugging at you from below, that gives the gorge its irresistible magnetism. Or maybe it’s the faint sound of the river that compels you to lean ever farther over the edge. Either way, at 48 miles long, the serrated knife slice into the state’s Western Slope is so dramatic, so vertigo-inducing, so inconceivable in its sheerness that you want to take a step back, you want to look away—but you can’t.

As American canyons go, the Black isn’t the deepest (that’s Hells Canyon in Idaho, at 8,043 feet) or the longest (see: Arizona’s 277-mile Grand Canyon), but no other gully in this country possesses its rare combination of extraordinary depth, verticality, narrowness, and darkness. It is for this reason, and so many others, that in 1999 federal lawmakers elevated the area’s status from national monument to national park, further protecting it from development.

When it comes to national parks, though, 47-square-mile Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park—which encompasses the 14 most scenic miles of the ravine—isn’t widely known. It is, in fact, among the least visited of the nation’s national parks, seeing only 308,962 visitors in 2018; in Colorado, it rides back seat to Rocky Mountain National Park, Mesa Verde National Park, and Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve. There’s little mystery why. A five-hour drive from the closest international airport in Denver and situated well away from major interstates, the Black could generously be called far-flung.

There are other reasons even the most ardent RV driving, iron-on patch collecting, zip-off pant wearing park enthusiast leaves this Colorado destination off his bucket list—namely, minimal infrastructure and inaccessibility. Unlike Yellowstone or Glacier national parks, Black Canyon has zero inside-the-boundaries lodges; the most luxurious setups available in the park are 23 reservable, RV-compatible sites with electrical hookups. That can be a turnoff for those accustomed to a more comfortable outdoorsy experience.

Furthermore, the inner canyon is a designated wilderness area, so there are no maintained trails leading to the Gunnison River at the bottom of the chasm. That in no way suggests visitors can’t get personal with the greenish-blue ribbon of trout-teeming water that, over millennia, carved the Black. What it does mean, though, is that only those with well-above average fitness, route-finding skills, and an abundance of gumption should consider venturing into the depths. Everyone else must be content to roam the North and South rims, taking in the dizzying views either by vehicle or via the handful of along-the-edge walking and hiking paths.

Coloradans, who make up more than 30 percent of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park’s visitors, seem to understand something the rest of America clearly doesn’t: Less is more, especially when it comes to people, roads, cars, and buildings in our wild places. The Black has all kinds of “less.” This first-timer’s guide explains why you should get there before more people figure that out.

Inside The Black

A by-the-numbers breakdown of Colorado’s most compelling canyon.

History: To Hell And Back

Whether it was at the behest of the railroad companies or in an effort to bring water to arid farmland, early explorers braved the canyon again and again. The Black spat out all but a hardy few.

The Gunnison Expedition

Who: John Gunnison

When: 1853

Mission: Gunnison and Co. were sent by the U.S. military on a crusade to survey a railroad route between the 38th and 39th parallels, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

Result: The party traveled along the Arkansas River, navigated the rugged Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and crossed the Continental Divide before coming upon what was then called the Grand River and its intimidating canyon. Gunnison (pictured above) wisely declared the gorge impassable and led his team around the South Rim.

For the Record: In what was the first written description of the Black, Gunnison deemed the terrain “the roughest, most hilly and most cut up” he had ever seen.

The Bryant Expedition

Who: Byron Bryant

When: 1883

Mission: The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad hired Bryant to survey the canyon and return with information about whether the company’s line could continue west through the middle and lower stretches of the canyon—and what that might cost.

Result: What was expected to be a 20-day exploration by a 12-man squad morphed into a 68-day slog that only five men had the stamina to complete. Bryant’s final report stated that bringing the railroad through the canyon would be financially disastrous.

For the Record: One of Bryant’s crewmembers, transitman Harvey Wright, wrote of the Black: “Hereto was unfolded view after view of the most wonderful, the most thrilling of rock exposures, one vanishing from view only to be replaced by another still more imposing.”

The Pelton Expedition

Who: John Pelton

When: 1900

Mission: As a resident of the Uncompahgre Valley, Pelton realized the farming community that sustained the mining industry needed more water for irrigation. By the 1890s, plots to tap the Gunnison River via a diversion tunnel were afoot. A team coalesced, and the journey aided by two wooden boats—to find a tunnel location began in the fall.

Result: On day two, one of the boats splintered apart in the rapids, sending supplies into the frigid water. The quest ended after a scant 14 miles.

For the Record: The Pelton party came up with a name for a gushing cascade near where the dejected team escaped the canyon: It was dubbed the Falls of Sorrow.

Torrence and Fellows Expedition

Who: William Torrence and Abraham Lincoln Fellows

When: 1901

Mission: A year after the Pelton Expedition, Torrence and Fellows resumed the probe for a diversion tunnel.

Result: The pair employed an inflatable mattress and rubber bags to ferry their equipment and often resorted to swimming. Their successful trip lasted 10 days. For two more years, Fellows surveyed the river; his work led to the start of construction in 1905.

For the Record: “At the Narrows the fun began,” Torrence wrote. “The canyon is full of great boulders, which form bridges across the stream. Over these we must scramble, one getting on top and pulling the other up. These rocks were slick as grease, and hard to climb. We spent a day in going a quarter of a mile.”

Lay of the Land

Mother Nature took extra care with the Gunnison River Basin, fairly begging Coloradans to protect its treasures. Over time, we have responded, creating conservancies along the waterway, from just five miles west of the town of Gunnison to outside of Delta. The back-to-back-to-back protected zones are an outdoor recreationist’s dream. Here, a primer on the conservation areas that bookend Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park.

Curecanti National Recreation Area

This 43,095-acre park, established in 1965 as part of the Upper Colorado River Storage Project, is composed of three reservoirs, including Blue Mesa Reservoir, the largest body of water in the state. As one might imagine, water-based activities are in ample supply. The surrounding landscape, sculpted by ancient volcanic eruptions and the rushing Gunnison into rugged mesas, plunging canyons, and pointy spires, offers plenty of dry fun, too. Hiking, horseback riding, birding, camping, and small- and large-game hunting are all on the menu. Where Curecanti ends, two miles below the Crystal Dam, the national park begins.

While You’re Here

- Fish for kokanee salmon on Blue Mesa Reservoir. During snagging season, which begins in November each year, fishermen can sight-cast to the sluggish, spawning fish, landing their hooks directly into the swimmers’ bodies.

- Hike the beautiful and well-constructed two-mile (one way) Curecanti Creek Trail from Pioneer Point to Morrow Point Reservoir; you’ll lose—and then gain—900 vertical feet.

- Make a reservation for a summertime-only Morrow Point Boat Tour ($24 for adults; $12 for kids). Park rangers take sightseers into the Black Canyon and explain local geology, wildlife, and history.

- Rent a pontoon boat ($209 for a half day) or an aluminum fishing boat ($85 for a half day) from the Elk Creek or Lake Fork marinas. It’s best to tool around Blue Mesa Reservoir during the morning, when the winds are calmer.

Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area & Wilderness

The far northwestern boundary of the national park is almost entirely enveloped by the Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area & Wilderness, 62,844 acres of Bureau of Land Management property. Outdoor activities abound here, but there are some things to know. First, user fees ($3 per person for day use; $10 per person for one night of camping) are required to access the wilderness and necessitate carrying exact change. Second, only 17,784 acres of the area are designated wilderness, which means visitors need to pay attention and adhere to varying regulations. With that said, the hiking, horseback riding, mountain biking, ATVing, white-water rafting, fly-fishing, nonmotorized boating, and camping here are top-shelf.

While You’re Here

- Sign up for a white-water rafting trip through the gorge with a local outfitter (we like Dvorak Expeditions). Accessing the river requires a four-wheel-drive vehicle and then a one-mile hike (even with an outfitter); rapids range from Class I to IV.

- Backcountry camp by the river. Start at the Ute Trailhead; reserve and pay for a campsite at the trailhead (Ute III has a nice beach); then hike 4.5 miles (one way) on a well-maintained path to the bottom of the ravine. Bring your fly rod.

- Book a multiday fly-fishing float trip through the gorge with an area outfitter (try Black Canyon Anglers or Rigs Fly Shop & Guide Service). These expeditions aren’t cheap, but Colorado Parks & Wildlife estimates there are 6,508 catchable fish per mile in the gorge. Your man-with-fish picture is a sure thing.

The Drive-By

More than 20 scenic overlooks inside the national park offer the easiest ways to experience the canyon’s grandeur.

Although the pine-log fencing and stone stanchions look sturdy enough, visitors tend to approach them with a certain level of apprehension at first. As well they should. Almost all of the 20 or so scenic overlooks in Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park allow visitors to inch their ways right up to the precipice, a position that simultaneously makes one feel like she is flying and falling.

For the vast majority of parkgoers, spending a day driving along South Rim Road—stopping at the visitor center and spots with promising names like Devils Lookout, Chasm View, and Painted Wall View (pictured)—is what visiting Black Canyon is all about. That is, of course, no different from how huge percentages of visitors experience Arches National Park in Utah or Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming or Redwoods National Park in California: Sightseers drive from arch to arch or from geyser to geyser or from big tree to big tree, usually in a line of cars.

Black Canyon rarely sees bumper-to-bumper traffic (note: July has the highest numbers) along the paved South Rim Road; however, the secret that even park rangers don’t want to share is the relative solitude of the North Rim. In July 2018, more than 46,600 people stopped at the South Rim visitor center, while only 1,282 parkgoers checked out the North Rim. Because there is no bridge over the canyon, accessing the North Rim requires a bit of a drive. You’ll need to allow two to three hours’ drive time from one rim to the other—but it’s entirely worth it. Not only are there far fewer people, but the views from the North Rim are also more dramatic, if that’s even possible.

Hikes We Like: Paths Of Least Resistance

The thing about canyons is that their rims are often blessedly flat, which translates to easy hiking trails with spectacular panoramas.

Warner Point Nature Trail | South Rim, 1.5 miles round trip

At the terminus of South Rim Road, leave from the ample parking lot at the High Point overlook to find the start of this easy walk along a well-trodden trail. Don’t pass up the illustrated walking guide pamphlets as you begin your jaunt, because this undulating path has 14 sites of interest that you’ll want to read about.

Look for: Pinyon junipers; the slow-growing, gnarled, ghostly trees thrive at these elevations.

Oak Flat Loop Trail | South Rim, 2 miles round trip

Leaving from the visitor center, the moderate Oak Flat Loop Trail gives the impression you’re headed into the canyon. And, if you’re looking for a little inner-canyon-esque adventure, the sometimes narrow path and steep traverses will give you a tiny taste of what that might be like—without all the pain.

Look for: An unmarked overlook on the final leg that affords amazing downstream views.

North Vista Trail to Exclamation Point | North Rim, 3 miles round trip

A kid-friendly stroll through juniper forests, this easy trip follows the rim, crossing rocky outcrops and smooth reddish-pink stone. The spur trail to Exclamation Point is well-marked, but watch the little ones in this area: There are no guardrails. The vistas of the inner canyon from Exclamation Point are some of the best in the park.

Look for: Views of S.O.B. Draw, a “path” down to the river.

Deadhorse Trail | North Rim, 5 miles round trip

Park at the Kneeling Camel View overlook and walk to what looks like an old service road leading to some vacant buildings, the remnants of an old ranger station. This trail leads away from the rim for a bit but meanders back for several dramatic views and, ultimately, a look at Deadhorse Gulch, a major tributary ravine of the Black.

Look for: East Portal Road, the only way to drive down to the river (see “River Trip” below).

River Trip

The only road in the park that leads to the water also takes visitors back in time.

The 16 percent grade doesn’t stress most contemporary vehicles. However, the same could not be said of the horse-drawn wagons East Portal Road was built to accommodate in 1904. To be fair, 32 percent grades plagued the original road, which led to East Portal, a settlement for tunnel diggers.

Today, East Portal Road is still the only way to reach the river—and revel in its sensory experience—inside the park using four wheels. The 250 inhabitants of early 1900s East Portal may not have been enchanted with their river-bottom home (clapboard housing is really drafty in January), but modern sightseers will be charmed by a stroll along the Devil’s Backbone Route. Even at lower flows, the Gunnison’s muscle is evident in swirling eddies. The summer air, redolent with scents of flora, feels cool coming off the 50-degree riffles. And the murmur of water over rock is oh so soothing.

Savvy parkgoers will pull up a patch of grass, watch for flashes of trout, and look for black bears. Those with time to ponder the randomness of life might consider this: how fortunate they are to be alive in 2019, when Subarus make the trip back up East Portal Road a cinch.

Into the Depths

It may not look like it, but hiking down into the canyon is possible—if you can hack it.

From atop a rocky pinnacle near the Chasm View overlook on the North Rim, park ranger Steve Kay points toward a nearly imperceptible ditch inside the canyon. “It’s kinda hard to see the route,” says the 38-year-old ranger, “but those boulders down there are tricky. Had a guy break his leg right there last year.”

Based on the topography of the general area Kay is referencing, this is not a surprise. The moniker given to this particular passage into the canyon—S.O.B. Draw—further confirms just how torturous it might feel to descend it. Yet, as Kay and a handful of other rangers confirm, S.O.B. Draw isn’t even the most challenging entry point to the inner canyon.

Because the innards of the Black within the park are designated wilderness, the National Park Service (NPS) is prohibited from building trails. In fact, the NPS can’t even erect signage to direct intrepid hikers—there were 3,399 of them in 2018—on the best ways to forge their own paths. What the NPS does do is twofold: One, it provides a brochure called “Exploring the Wilderness” that explains where the six rim-to-river access points are. And, two, if you ask a ranger in the visitor center (highly, highly advised) to help you plan an inner canyon hike, he or she will deliver instructions and pointers to aid your trek in addition to assisting you in filling out the mandatory, free wilderness permit* you’ll need for a dayhike or an overnight stay.

Kay explains that the inner canyon routes are doable for most physically fit people so long as they respect the challenge and take responsibility for themselves. That means starting early in the morning and taking plenty of water (four liters per person, per day), enough food to sustain you for 24 hours longer than you plan to be out, a headlamp, fire starter and waterproof matches (for emergency use only; campfires are prohibited), and a first-aid kit. “If you have all that, you should be fine,” Kay says. “Then all you have to worry about is the suffering.”

*If you arrive after visitor center (South Rim) or ranger station (North Rim) hours, you can self-permit so long as daily hiker limits—which range from five to 20 depending on the draw—haven’t been exceeded.

Suffer Scale

Inner canyon routes ranked according to pain inflicted (least to worst).

Gunnison Route

Distance: 1 mile

Vertical Drop: 1,800 ft.

The park’s most-trodden trail, this path is accessible from the South Rim visitor center. That doesn’t mean, however, that it is a walk in the (national) park.

Long Draw

Distance: 1 mile

Vertical Drop: 1,800 ft.

Also known as Devil’s Slide, this short but sheer passage from the North Rim asks hikers to crawl down boulders, some of which can be loose.

S.O.B. Draw

Distance: 1.75 miles

Vertical Drop: 1,800 ft.

This is the North Rim’s version of a beginner’s trail. It’s still arduous, and missteps can be literal ankle-breakers, but the real issue is poison ivy.

Tomichi Route

Distance: 1 mile

Vertical Drop: 1,960 ft.

A scree field from rim to river makes this the South Rim’s most technically challenging trail.

Warner Route

Distance: 2.75 miles

Vertical Drop: 2,722 ft.

You’ll travel to the deepest part of the Black, making this a long—yet still painfully precipitous—route. An overnight stay is a must.

Slide Draw

Distance: 1 mile

Vertical Drop: 1,620 ft.

Poor footing, loose rock, and a 30-foot downclimb to start this North Rim route make it the most excruciating and dangerous way down.

Poison Control: Rash Guard

Hikers in the Black should remember the old adage “Leaves of three, let it be,” because poison ivy absolutely proliferates in the canyon. We consulted UCHealth dermatologist Dr. Cory Dunnick and Denver Botanic Gardens’ horticulturist Kevin Williams to help you avoid the agony.

- Poison ivy has a compound leaf, meaning each leaf comprises three leaflets. It’s difficult to identify poison ivy because, Williams says, it is “morphologically variable.” Translation: Not every plant looks the same (some have leaves with smooth edges, some have leaves with toothy edges), and the plant can change appearance based on season. Spring leaves can affect a reddish tint; summer foliage is light green and glossy with greenish-white berries; and in the fall, leaves can turn orangey yellow.

- In Colorado, the native species is Western poison ivy. It’s usually more shrublike than its more viny Eastern sibling.

- The rash, which typically lasts five to 14 days, is caused by urushiol, a clear liquid compound in the plant’s sap. Urushiol is found in the leaves and stems any time of year. Be forewarned: Even dead plants can cause irritation.

- Roughly 15 percent of the planet’s population won’t experience a reaction to poison ivy; however, repeated exposure often ups your risk.

- An adaptable plant, poison ivy species grow throughout North America. In Colorado, it does well in wet lowlands or in river basins.

- Over-the-counter topical steroid creams, like hydrocortisone, are a sensible option if you develop an itchy rash. If your irritation seems particularly severe, Dunnick says, go to your general practitioner or dermatologist for prescription-strength medication.

- If you come into contact with poison ivy, Dunnick recommends removing affected clothing carefully (urushiol can cling to surfaces) and dumping it into the washer. Then shower post-haste, washing contact areas with soap and water. Using products like Tecnu, a poison ivy wash, can’t hurt and can be helpful if a shower isn’t handy.

- Do not burn poison ivy in your campfire. “The oil can become aerosolized,” Dunnick says, “and then you can have terrible exposure to your face and eyelids.”

- Remember that your pet might pick up urushiol on its fur. If you then pet him, the oil will transfer to you.

- Prevention is key, Dunnick says. Her best advice is protective clothing, but she also suggests using a barrier cream, like IvyX, to prevent oil from reaching the skin.

Hitting the Jackpot

Why anglers, hikers, and backpackers vie for coveted Red Rock Canyon permits each year.

There were only 1,128 chances to access the Black through its super-secret back door in 2019. And if you haven’t already secured one of those spots, you’ll have to wait until December for your next attempt at the Red Rock Canyon lottery.

Red Rock Canyon is located near the South Rim, but access requires traveling through private property. As such, the park has worked with land owners to allow limited passage to one of the more gradual routes leading into the canyon within the park. At 3.4 miles long with a vertical drop of only 1,330 feet, the unmarked “trail” isn’t leisurely, but backpackers and anglers carrying gear greatly prefer the milder grade.

To have a shot at one of the route’s two campsites and two miles of river access, Red Rock Canyon hopefuls must apply, usually beginning in late December; the application window closes in early March. There are restrictions—e.g., groups are capped at four and only allowed three consecutive days—but for those who’ve always wanted to trek into the Black but were scared off by the rim-to-river free falls, applying is easy enough. It’s waiting to find out if you’re one of the lucky few that’s difficult.

Cliffhanger

After years of passive spectating, it was time for me to take the plunge.

To be honest, I just didn’t believe him. No matter how earnest and knowledgeable he seemed, the park ranger’s assertion that one could hike to the bottom of the Black Canyon seemed absurd. With ropes? I asked. Or maybe a parachute? With a gosh-golly-gee-whiz demeanor, he explained that someone with my fitness level could do it, no problem.

Roughly 15 years—and four trips to the canyon—later, I was finally ready to test his claim. I was a decade and a half older, but my physical condition was still above average (although I’m not a marathoner or anything). I had done the research. I had donned the right footwear; invited a hiking partner; topped off our water bottles; and filled my daypack with the necessities of backcountry travel. I had spent 30 minutes in the South Rim visitor center getting the 411 on the Gunnison Route from another equally eager ranger, and I had filled out the free wilderness permit that allowed me to venture beyond the “Wilderness Permit Required” sign at the drop-in point. What I hadn’t really done was prepared myself mentally for the journey.

I realized this only after I had tripped over a large root, then skinned my knee on a small boulder, and later felt my toes jamming into my shoes as they begged for relief from gravity. The Gunnison Route is arguably the easiest path to the river, but that’s not to say it’s easy. After the wilderness sign, the draw breaks down into four sections: a quarter-mile of smooth switchbacking dirt; a quarter-mile of rock-laden trail; a quarter-mile of a steeply dropping path, highlighted by an 80-foot-long chain used to aid your descent; and a final section of loose scree where crab walking becomes your best mode of movement. On the final three sections, I think “controlled falling” is a better phrase for describing my progress than “hiking.”

My knee was scraped up and I was covered in dirt, but I made it to the river in one hour and 55 minutes. And, well, it was glorious at the bottom. I found a riverside boulder, stripped off my shoes, submerged my toes in the water, and soaked in the views. My hiking partner sallied upstream to get a line wet and reeled in two rainbows on a black-wing hopper.

Not knowing how long our ascent would take, we left as the afternoon began to shorten. It was on our way up that we realized how critical our chat with the ranger had been. She had advised us to stop periodically as we descended to look back up the way we had come, noting landmarks to make our return easier. Thank God we listened to her; we could have gone the wrong way at least twice. It took one hour and 40 minutes to claw our way back to the rim. My thighs were burning. Even my biceps and triceps, which got a workout hauling my weight over boulders, were screaming. As I reached the end of the trail, though, I smiled through the pain. My ranger friend from 15 years earlier had been right after all.

I Spy

Although they’re frowned upon in wilderness areas, hikers often leave impermanent trail markers for fellow adventurers. Be on the lookout for:

Q&A: Flying High

Black Canyon is a birder’s paradise. We asked Bruce Ackerman, president of the Black Canyon Audubon Society, why that’s the case.

5280: What makes a canyon a desirable habitat for birds?

Bruce Ackerman: The canyon itself is the unique habitat. There are many types of birds—such as peregrine falcons, golden eagles, ravens, white-throated swifts, canyon wrens—that nest only on cliffs. So, there is abundant habitat for them. But the low, scrubby vegetation on the rims is excellent habitat, too.

What should parkgoers be looking for? And when?

Mountain bluebirds, Western scrub jays, white-throated swifts, Steller’s jays, black-billed magpies, Clark’s nutcrackers, Western tanagers, and violet-green swallows are easy to see and often unfamiliar to people who live in other parts of the United States. These species are present during the warm months, but only a few stay over the winter. Early morning is usually the peak time to see the most variety of birds. Definitely bring binoculars.

Let’s say you’re a serious twitcher—what might you add to your collection at the Black?

Most experienced birders locate birds initially by their sounds. Canyon wrens and rock wrens are two species that are easier to find by sound. Birdwatchers would also want to see peregrine falcons and golden eagles nesting on the cliffs; dusky grouse doing their spring mating ritual; and white-throated swifts and violet-green swallows zooming along the cliff edges to catch insects.

What’s your favorite park overlook?

Peregrine falcons most commonly nest in the Painted Wall, so I always visit the Painted Wall View.

Leisure Interests

We can’t imagine it will, but if gazing at the canyon gets old, feel free to try one of these more active pursuits.

If you like to…fly-fish and you don’t mind a strenuous 1.75-mile, 1,800 vertical-foot-drop hike, you can find two beautiful miles of river access at the bottom of S.O.B. Draw—but keep in mind that you need a fishing license; rainbows are catch and release; and bag and possession limits apply to brown trout.

If you like to…kayak and you are an expert paddler with loads and loads of adventuring experience, you can put in at East Portal and take out at Chukar Trail, 14.3 miles downstream, but keep in mind that the rapids here are Class V; there are numerous dangerous portages; and according to the national park, “death is probable” for anyone trying to run this section at a flow rate higher than 3,000 CFS.

If you like to…cross-country ski and you like the whole walking in a winter wonderland thing, you can park at the visitor center and then slip-slide your way for six miles on the groomer-for-skiers South Rim Road, but keep in mind that winter temps can be downright frigid; weather can roll in quickly; and there are no places to take shelter should you be unprepared for the worst.

If you like to…rock climb and you are an experienced climber who digs multi-pitch climbing, you can check out Maiden Voyage (5.9-), Comic Relief (5.10), and Scenic Cruise (5.10+), three of the park’s most popular multi-pitch climbs, but keep in mind that much of the climbing in the Black is “committing,” which means once you start you cannot stop until you reach the rim.

If you like to…ice climb and you like beautiful views, too, you can try either Gandalf’s Beard, a two-pitch climb east of Chasm View overlook, or Shadowfax, a two-pitcher located off East Portal Road, but keep in mind that Gandalf’s Beard has failed to fully materialize for the past several years; call the visitor center for up-to-date information just in case the wizard has, once again, been delayed.

The Car-Camping Chronicles

Most people who plan to overnight inside the park stay in one of three locales—the South Rim, the North Rim, or the East Portal campgrounds. In the summer, most of the South Rim’s 88 campsites are reservable via recreation.gov ($16 to $22 per night, plus a $3 reservation fee). The 15 sites ($16 per night; no RVs) at East Portal and 13 sites ($16 per night) at the North Rim are first come, first served and close seasonally. These RV- and tent-laden settlements are much like those in any other national park; however, the difference between being at the Black and being at a campground in, say, Rocky Mountain National Park is the relative isolation. From South Rim and East Portal, it’s a 30-minute drive to the closest big-box grocer; from the North Rim, it’s 40 minutes. In short: Knowing what you need before you arrive is key.

1. Set Your Sites

The South Rim

Open year-round, the South Rim Campground has three loops, each with its own set of regulations. All 88 sites accommodate tents and/or small RVs. A Loop has several sites for medium-size trailers, and reservations are accepted. B Loop makes room for larger trailers, takes reservations, and has electrical hookups in the summer. C Loop is first come, first served and only accommodates small RVs. Generators throughout are a no-no. Reservations must be made at least three days in advance. Dogs on leash are generally allowed in all park campsites, but visit Black Canyon’s website for specific rules. Best sites: A31, B23, and C18

The North Rim

This campground is typically open from April to mid-November and has 13 sites. All sites accommodate tents; RVs are allowed, but sizes greater than 35 feet are not recommended and there are no hookups. Generator use is allowed during designated times. All sites are first come, first served. Best sites: 1 and 4

The East Portal

Sites here are usually open from May to mid-October; the campground has 15 sites. All sites are first come, first served and accommodate tents; RVs are prohibited. Best sites: Any spot in the lower tier, away from the entrance station

2. Light My Fire

All campsites are equipped with fire rings with grilling grates, but campers must bring their own firewood. Collecting wood—dead or alive—inside the park is forbidden. Campfires outside of fire rings are prohibited.

3. Table Service

Each site has a wooden picnic table, but we suggest bringing comfortable camp chairs for around the fire ring.

4. From the Tap

Water is generally available in all three campgrounds from mid-May through mid-September. RV-filling is not available.

5. Bear Prepared

Bears roam the Black. Place all “smellables”—food, scented toiletries—in the bear boxes or lockable dumpsters at night.

6. Nature Calls

All Black Canyon campgrounds have vault toilets, (usually) supplied with toilet paper. But you might want to bring an extra roll, just in case.

7. Zero Bars

You’re in the great outdoors, people: Don’t expect cell service.

8. Look Up

The Black was designated as an International Dark Sky Park in 2015. The classification means the park offers exceptional star viewing because of the area’s minimal light pollution. Mark your calendar: The park is hosting an astronomy festival, with guest speakers and special activities, from June 26 to 29.

Road-Trip Restaurants

Along Highway 50, on either side of the national park’s South Rim entrance, sit two lovely little burgs perfect for a pit stop, no matter what time you arrive.

Gunnison

Population: 6,530

Extra Early in the Morning: Come 6 a.m., Tributary Coffee Roasters has whatever version of caffeine you might crave, but the Americano is particularly satisfying. The from-scratch lemon-ginger scone serves as a not-too-sweet complement. 120 N. Main St.

Breakfast: If you’re into traditional American diners, the W Cafe will do you right. Whatever you order, get a biscuit on the side. 114 N. Main St.

Lunchtime: Firebrand Delicatessen is your quintessential mountain town sandwich shop (heads up, it’s cash-only). Service is a little slow and a lot sweet, and the grub is exactly what you’re looking for midday. 108 N. Main St., 970-641-6266

Happy Hour: Between 4 and 6 p.m., nab a table on the sunny upstairs deck, then select a happy hour pint from High Alpine Brewing’s roster of roughly 10 rotating beers. 111 N. Main St.

Dinner: Make a meal out of Blackstock Bistro’s small plates, or indulge in entrées like the coconut curry or St. Louis ribs. 122 W. Tomichi Ave.

Montrose

Population: 19,305

Extra Early in the Morning: Located in an adorable little old house right along Main Street, the Coffee Trader pours a great drip. 845 E. Main St.

Breakfast: Those planning inner canyon hikes should take this opportunity to carbo-load at the Backstreet Bagel Company. Don’t miss the signature green chile bagel with cream cheese schmear. 127 N. Townsend Ave., 970-240-3675

Lunchtime: Colorado Boy Pizzeria & Brewery makes its dough in-house with local-grain flour, salt, water, yeast, and—according to its menu—love. The beer seems to benefit from similar devotion. Grab a crowler to go for fireside sipping. 320 E. Main St.

Dinner: It’s not fancy, but dining at Trattoria di Sofia is akin to eating at your nonna’s house. You know, if your grandma made a mean Bolognese. 110 N. Townsend Ave., 970-249-0433

Late Night: Phelanies is a speakeasy of the highest caliber. Try the Old Smokey, a twist on an old fashioned with a smoke-rinsed glass. 19 S. Junction Ave.

If You Go: Travel Agency

The details you need for planning the trip you want.

Operating Hours: The South Rim is open every day of the year, but during the winter, South Rim Road is only plowed up to the visitor center. The North Rim and East Portal Road are generally open from mid-April to mid-November.

Entrance Fees: $20 for noncommercial vehicles and all occupants; $15 for motorcycles (covers two visitors); $10 per cyclist or pedestrian

Visitor Center: The South Rim visitor center is open every day except Thanksgiving and Christmas. Summer hours are generally between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. Offseason hours are typically from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m.