The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Fifty years ago, Congress passed the Wilderness Act to safeguard the country’s raw swaths of nature from development, but much of Colorado’s spectacular terrain remains vulnerable. On the golden anniversary of this landmark law, we explore seven stunning landscapes that may warrant some measure of lasting security. As civilization encroaches, the question remains: How much longer can our iconic environment wait?

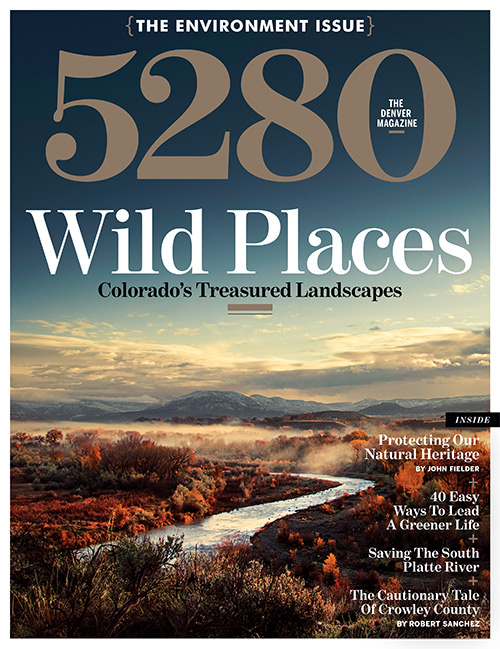

The Northern Dolores River Watershed

(pictured, above)

The west fork of the Dolores River begins as a trickle in the San Juan Mountains’ Lizard Head Wilderness before cutting its way through red rock canyon country and ultimately out to the Colorado River in Utah. The southwestern Colorado terrain surrounding the river is among the few landscapes in the country of its kind that remain mostly unscathed by development. Yet threats from climate change, off-road-vehicle use, uranium mining, oil and gas development, and unchecked recreational use could endanger a dwindling population of desert bighorn sheep, further degrade the ecological conditions downstream of McPhee Reservoir, and mar a landscape that can be experienced today much as it was 100 years ago. Currently, there are three Wilderness Study Areas on the upper watershed and a proposal to establish a National Conservation Area on the lower section of the river.

Red Cloud Peak Wilderness Study Area

The 38,495-acre Red Cloud Peak Wilderness Study Area—a provisional label for regions Congress says may warrant protection—near Lake City contains 30 thirteeners and two fourteeners: 14,034-foot Red Cloud Peak (the view from which is pictured) and 14,001-foot Sunshine Peak. The area offers fragile alpine tundra, densely forested lower elevations, rock glacier formations, gin-clear streams, and alpine lakes. Abundant wildlife—mule deer, elk, bighorn sheep, cutthroat trout, and the Uncompahgre fritillary butterfly—takes refuge in the spruce-fir forest, native grasses, and small willows. Should Congress ever discontinue Red Cloud Peak’s Wilderness Study Area designation, mining operations and new roads could imperil the area’s delicate ecosystems.

—Photo by Jack Brauer

Hermosa Creek Watershed

In 2013, federal legislation was put forth in both the U.S. House and Senate to protect the Hermosa Creek watershed, an area that encompasses one of Colorado’s largest and most biologically diverse forests, including at least 17 separate ecosystems. That legislation—which is still languishing in Congress—would deem 107,886 acres protected from roads, development, and resource extraction with the aim to maintain water-supply purity, bolster economic prosperity, protect native Colorado River cutthroat trout, and support recreational uses. The proposal also would designate 68,289 acres as the Hermosa Creek Special Management Area (which would keep the area’s famous mountain biking trails open) and approximately 37,000 acres as the Hermosa Creek Wilderness Area.

—Photo by Joshua Duplechian

North Park

A high-alpine-valley wonderland of wildlife, lakes, streams, and stunning views of the Mount Zirkel and Never Summer wilderness areas, Jackson County’s North Park contains nearly 20 percent of Colorado’s greater sage-grouse population. It’s also home to numerous species of migratory waterfowl; hosts herds of big game (moose were introduced to Colorado in North Park in 1979); and offers some of the best trophy fishing in the state. But the area faces serious threats from recent crude-oil spills and (for now, legal) wastewater dumping that have altered the natural makeup of creeks, created oil stains along stream banks, and, in some places, encouraged algae blooms in the area’s waters.

Greater Sage-Grouse Habitat

Northwestern Colorado—specifically areas in and around Moffat County—is marked by vast seas of sagebrush, the favored habitat of the greater sage-grouse (pictured). But this hearty, drought-resistant landscape is one of the most jeopardized ecosystems in the country, facing threats from development, oil and gas drilling, wind farms, and wildfire. The fates of sagebrush lands and the greater sage-grouse are, of course, intertwined. Currently, greater sage-grouse populations are dwindling; if they continue to decrease in numbers, the greater sage-grouse could join the Gunnison sage-grouse on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s list of threatened species.

—Photo by Tandemstock

Browns Canyon

The battle to protect this granite canyon cut by the Arkansas River between Buena Vista and Salida has raged for decades. Legislation supported by the community as well as local rafters—the canyon is home to some of the country’s best white water—and proposed by U.S. Senator Mark Udall in March 2013 has renewed the effort to protect this stretch of land and water, which provides outstanding fish and wildlife habitat as well as four-season recreational opportunities. Supporters of the almost universally well-received bill—which could potentially protect about 20,000 acres using the National Monument label and 10,000 acres under the wilderness moniker—say protecting the land from new roads, development, and gold mining is not only good environmental stewardship but also safeguards the $60 million annual economic impact of the white-water boating industry.

—Photo by Joshua Duplechian

Comanche National Grassland

More than 440,000 acres of juniper woodlands, forested mesas, red rock canyons, and the last intact short-grass prairie in America’s Great Plains make up Comanche National Grassland in southeastern Colorado. Currently managed by the U.S. Forest Service, this ecologically and historically rich setting (the area includes 150-million-year-old dinosaur tracks) spent much of the past decade under threat from the Pentagon’s proposed expansion of the U.S. Army’s Piñon Canyon Maneuver Site, a plan that was abandoned in November 2013. But that doesn’t mean the area is in the clear: Grasslands are an endangered ecoregion, and further development—whether it comes from the Army or oil and gas companies—could mean a loss of vegetation and increased erosion that could harm the habitat of native species (such as the lesser prairie chicken, which was federally listed in March as threatened under the Endangered Species Act) and imperil the area’s archaeological and paleontological treasures.

—Photo by David Muench/Corbis