The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

There is no mistaking the drama of a night at the theater: Lights dim over the audience, the first note of music hangs in the air, a moment of anticipation fills the space before the opening line is delivered. To borrow the words of Daniel Ritchie, one of Denver’s most philanthropic supporters of the performing arts: “Theater is an adventure.”

Although Ritchie meant that affectionately, he knows as well as anyone that adventures are often characterized as such for their excitement, boldness, and, above all, inherent riskiness. The theater business is a precarious one—even in places well known for the performing arts. In Denver, a town that forever seems on the brink of becoming an arts haven, about 50 theater companies are currently trying to keep the lights on each season.

It’s no easy task. Up-front costs (rent, actors’ salaries, sets, support staff, the rights to produce a work) add up quickly—and gauging whether audiences will be interested enough in a show to recoup those expenses is a guessing game at best. In the past, arts organizations often relied on large foundation grants to subsidize certain line items—or make up for a lackluster turnout—but since the recession, that money is more difficult to come by. “Funding for the arts has become more challenging,” says Tariana Navas-Nieves, director of cultural affairs for Denver Arts & Venues. That includes the audience side of the equation. Nationally, full-season subscriptions to theater companies are down; more often, theatergoers are buying tickets to particular shows just a few days in advance, a few times a season. “You constantly have to be aware of what your value is for the community,” says Kent Thompson, producing artistic director for the Denver Center Theatre Company.

In Denver, there is no question the theater scene supplies a valuable commodity. From avant-garde shows to productions fit for niche audiences to original comedies, there is something to suit every taste. But if local audiences want to keep their options broad, and if we want to support the actors trying to make a living here, the solution is simple: Buy a ticket. (Or two. Or five.) Then let yourself be swept up in the adventure.

In the Making

What does it take to bring a new play to the stage? Kent Thompson, producing artistic director for the Denver Center Theatre Company, walks us through his process. —DS

Step 1

The Denver Center hosts its annual Colorado New Play Summit (February 14 to 22, 2015) with the intention of showcasing plays that have never been produced professionally. Before the event, Thompson and his team—four staffers and six volunteer readers (anyone can contact the literary department and offer to help)—wade through 500 to 700 submissions from playwrights around the country.

Step 2

Every play is read by at least two people. Readers fill out a standardized form that includes queries on plot, cast size, special requirements, and, most important, whether they would advocate for the play to be produced at the Denver Center.

Step 3

The massive pile is whittled down to a manageable size. At this point, the decisions required to narrow the short list down to the final four or five resemble a jigsaw puzzle, with Thompson and team considering themes, number of actors, diversity of playwrights, and more. The five-month process results in two plays eventually getting world premieres at the Summit (the other finalists typically receive readings or workshops). “Our ground rule is the writing needs to be good,” Thompson says. “The plot, characters’ motivations, and the story itself need to be moving, thought-provoking, and contemporary. New plays are an artistic snapshot of today.”

Step 4

For the two shows receiving full-blown productions, the first step is deciding on a director. Then Thompson, the playwright, and the director set about selecting a creative team—which can include some of the Denver Center’s resident designers—and begin discussing casting.

Step 5

A design production meeting is held in which the team determines the budget and starts figuring out set and costume designs and the technical demands of the show.

Step 6

During the four months before opening night, Thompson and the director oversee the design process, checking in on sketches, fabric choices, color decisions, and more.

Step 7

While local actors are often considered for roles, the more limited pool here means casting calls may also be held in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Step 8

Thompson and associate artistic director Bruce Sevy attend rehearsals and a week of previews. Sometimes the playwright’s rewriting process and rejiggering of scenes may continue until opening night. Those last-minute changes don’t just affect the actors’ lines—every scene change needs to be re-teched and stage directions must be altered. “Producing a new play is probably two to three times the labor of producing a known play,” Thompson says.

Step 9

Opening night!

Telling Stories

There was a moment during Denverite Steven Cole Hughes’ senior year of high school when he was forced to choose between soccer and performing in the school play. He chose the theater—and audiences have been applauding ever since. Over the past decade, the now-40-year-old has written nearly a dozen plays that have been produced all over Colorado. We sat down with Hughes to talk about his creative process and how playwrights make a living. —Chris Outcalt

What is the primary goal of a playwright?

To entertain an audience. There is nothing more important than telling a story. Does your play have a beginning, middle, and end? Is it going to be fun or interesting or sad or edifying to an audience? I don’t care what its literary merits are; our first and last job is to tell a story to the audience—that’s one of the things that’s going to keep theater alive.

Do you remember what pieces of writing you first connected with?

I think what really drew me to writing was Monty Python and Abbott and Costello. When I heard “Who’s on First?” I remember the first thing I thought, even as a kid, was, That is brilliant writing.

It’s interesting that you chose live performance. Is there a difference between writing something that will be performed as opposed to read?

Theater was invented in Greece, and they used to go to hear a play, not see a play. Plays are meant to be heard, not read. I have a trilogy of Old West plays [Slabtown, Billy Hell, and The Bad Man] that require horses and all this stuff, and to look at that on the page is weird. It’s not the playwright’s job to say, “This is how you’re going to create a horse effect” or “This is how you’re going to have a believable gun fight inside a saloon.” You let the director and the production manager and the designer figure all that out.

Can playwrights make a living just writing plays?

No one can make a living as a playwright. All playwrights do other things. There’s a big trend now where a lot of playwrights are getting work writing for TV. I think one of the reasons The Wire is one of the best shows in the history of the medium is because David Simon got a different playwright to co-write each season with him.

You’re also an actor. Does that inform your writing?

As a playwright I never want to write a character that wouldn’t be fun to act. If there’s a role I have that’s not fun or challenging or the storyline isn’t clear, I’m able to identify that as an actor and fix it. Playwright is spelled “w-r-i-g-h-t” because plays are not written, they are wrought. They are brought to life by a group of people. It’s not just a solitary, lonely thing.

5280.com Exclusive: Read our extended Q&A with Hughes below.

How do you tell how a play will sound while you’re writing it?

As soon as I feel comfortable with my first draft, I get my actor friends to read it out loud. I either have them come over to my apartment, or I get a little studio. Sometimes if I feel comfortable enough I’ll have them read it in front of a small invited audience. That’s the way to see if your play works or not.

Do you tell them anything about the play before they read it?

I don’t like to say anything about the play because I want it to speak for itself; if it doesn’t, then I’ve not done my job. I don’t follow along. I just sit there and watch and listen. That’s the true test. If you follow along on the page, you’re not really getting the experience.

How important is it to have a good relationship with a director?

A good director is hugely important. I’ve been fortunate enough to work a lot with Maurice LaMee who used to be the artistic director of the Creede Repertory Theatre. He directed all three of my Western trilogy plays. Now he’s the director of the Aspen Writers’ Foundation. One of the most important things I learned from him is that in theater you have to make difficult, brave choices. In my very first play he produced, he cast an actor who was wrong for the role and just did not get it. It’s a very short rehearsal process in Creede, only three weeks; after the first week he realized that actor was not working out, and he fired him and said, “I’m sorry, it’s my fault; I cast you in the wrong role.” He replaced him with somebody else and immediately the play was 100 times better. I was so impressed and inspired by that because that’s a brave thing to do.

What is your writing process like? Do you start with story? Characters?

For me, it always starts with a story. Then I think, Who are the characters who are going to populate this story? Something that has happened to playwriting is that budgets for theaters all around the country have been slashed. So the fewer characters you have in your play, the better chance you have at your play being produced. I think that started off as a budgetary necessity, but now I think the form has just changed. We no longer have three-act plays that have 12 people in them, one of whom is a servant and only has two lines. Now we have one-act plays that have two or three people in them. That’s how we tell stories.

How important is acting to your career?

Acting is certainly how I make my living. You get paid way more as an actor than you do as a playwright. You get paid more to do anything—be a director, be a designer, be a stage designer. It’s crazy that playwrights are the lifeblood of this art form, the creators, and everybody is working on their plays, and they’re the ones who get paid the least. If I tried to survive just as a playwright I wouldn’t even come close. I could pay one month’s rent every year from my income as a playwright.

Know Your Lines

Expand your theater vocab. —Dylan Owens

World premiere: A full-fledged performance that’s never been produced before—anywhere. It can, however, have been part of a workshop or presented in a reading.

Regional premiere: A production’s first performance in a given area of the country. Colorado is typically thought of as part of the Rocky Mountain region or the West.

Rolling premiere: A production that premieres in a number of theaters over the course of one season, often with the playwright making changes with each showing.

Director: The person who oversees every aspect of the production—working particularly closely with the actors and designers—and determines how a given work will be interpreted.

Presenting house: A theater or company that houses and markets a performance (say, The Book of Mormon at the Buell Theatre) but usually doesn’t have anything to do with the cast or production decisions.

Producing house: A theater that is involved in every aspect of a play, from hiring the director to building the sets to casting to marketing.

Upstage: To be “upstage” means to be farther from the audience than “downstage.” When an actor addresses another from upstage, it forces the latter to turn his back to the audience. Hence the phrase “being upstaged.”

Ghost light: A light onstage that’s left on when the space isn’t in use. It’s practical—the stage is often littered with objects that could cause injury in the dark—but it’s also based on superstition: The beam is thought to ward off ghosts who would otherwise haunt the area or disrupt performances.

Calling The Plays

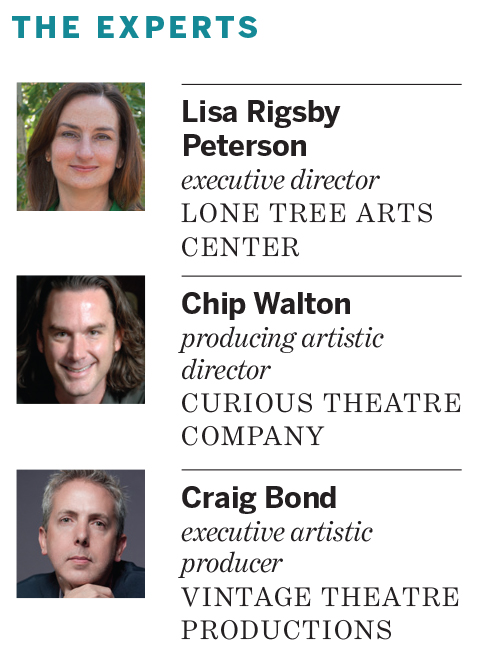

Three experts provide the scoop on the four most important factors in choosing a full theater season. —Lindsey B. Koehler

What Their Audience Wants to See

In its fourth season, Lone Tree Arts Center (primarily a presenting house; see “Know Your Lines”) is still doing some guesswork when it comes to figuring out what moves its audience. “We have to satisfy enough tastes to generate the revenue we need,” Rigsby Peterson says. “While we’d like to eventually take more artistic risks, we need the broad appeal right now.” For the 2014-15 season, that means attracting fans of classics (with Guys & Dolls In-Concert), comedies (from Denver’s Buntport Theater), and musicals (such as Fancy Nancy, a children’s production, from New York’s Vital Theatre Company).

What They Can Afford to Put Onstage

Curious Theatre Company has a $1.3 million estimated annual budget—which gets eaten up pretty quickly with all the variables Walton has to take into account when planning a season. That lengthy list includes: how many actors a play requires and how many are union versus nonunion (union contracts are more expensive); if he can find local actors or if he’ll need to pay travel and housing expenses for out-of-town performers; fees associated with paying for the rights to a play; and set design. Then he has to have faith that what he’s chosen to produce will fill the 180-seat theater with enough patrons to pay for it all. “I don’t know what’s going to sell,” Walton says. “Not for sure, anyway.”

Whether Their Lineups Will Draw New Audiences

Vintage Theatre Productions has been on the Denver scene for 12 years, which means Bond’s company has a good base of regular viewers—385 annual subscribers, in fact. But every playhouse depends on single-ticket sales to fill out its seats—and its coffers. “I’m always trying to find shows that might connect with different populations,” Bond says. “You need to mix up your season to get new people in the doors while keeping true to a base of subscribers.” Many times, that can mean doing plays that haven’t often been produced in Denver, such as The Spitfire Grill (coming in 2015).

How the Calendar Pans Out

The theater season usually runs from early fall through late spring. That seems like plenty of time—until the realities of the business begin unfolding. “Our audiences want to go to the theater on the weekend,” Rigsby Peterson says. “That’s fine, except these troupes may only be able to play at my arts center on a Tuesday.” Vintage’s Bond agrees that the logistics often become a limiting factor. “I had a beautiful season sketched out for 2015,” he says, “but then I found out that for four of the 11 shows I wanted to produce, I couldn’t get the rights. That’ll really blow up your season.”

What A View

The front row may be the obvious choice, but it’s not always the right one. We asked six theaters to divulge their best seats. —Lindsey R. McKissick

Stage Theatre

Section 2, Row D, Seat 16

The upper section of this fan-shaped theater features unobstructed sight lines and a wider-than-average aisle that creates extra legroom for patrons enjoying the show from the comfortable end seats.

Lone Tree Arts Center

Orchestra Front Center, Row F, Seat 107

Lucky seat 107 tucks dead center into the last row of orchestra seating. You can’t do better—straight-on view, no people fidgeting behind you—in this 484-seat auditorium.

Avenue Theater

Center Section, Back Row, Seats 1–4

This tiny row at Avenue has just four seats, but what it lacks in size it makes up for in amenities: Located less than 15 feet from the stage, this vantage point comes with more legroom than anywhere else in the house.

Carsen Theatre at Dairy Center for the Arts

Row C, Seat 7

This chair, one of 80 in the Boulder venue, places you square in the center of the stage, a few rows back from the front, for a welcome big-picture perspective.

Dangerous Theatre

Second Row, Center Tables

We’re looking out for your best interests here: The cabaret-style seating for 40 people at Dangerous is, well, intimate. Of the five rows of table seating, the first is just a foot from the stage. And when there are naked folks up there—yes, it’s happened; no, it’s not the norm—having an extra row between you and the…um…talent just makes sense.

Spark Theater

Front Row, Middle Seats

This tiny venue has only two rows and the seats aren’t numbered—or assigned. Arrive early to sit, literally, front and center (in this case, it is the best).

The Thrifty Theatergoer

A night on the town doesn’t have to empty your wallet. Here, six ways to save some money for a nightcap. —Drew Grossman

$20 | Vintage Theatre

Be picky. If you can’t (or don’t want to) commit to a full season, drop $120 for a six-production package. (That’s only $20 a show.) vintagetheatre.com

$10 | Denver Center Theatre Company

Every Tuesday at 10 a.m., the Denver Center releases a minimum of 10 $10 tickets to every Theatre Company performance in the coming week. For younger thespians: Student rush tickets ($10 with a valid student ID) are offered an hour before showtime. denvercenter.org

$15 | Dangerous Theatre

The $90 Dangerous Player Card is good for six tickets to any performance, or you can spread the pass over multiple productions (or split it among friends). Bonus: Unused punch cards don’t expire. dangeroustheatre.com

Free | Boulder Ensemble Theatre Company

Patrons age 25 and younger can participate in free ticket rushes (yes, free, really), which take place 10 minutes before all performances if tickets remain. betc.org

$18 | Curious Theatre Company

Buy the $85 preview subscription package to access preview nights (the Thursdays and Fridays before opening nights) for five productions. Or check the website to score an $18 single ticket, available for Thursday and Sunday performances (tickets are typically $25 to $44). curioustheatre.org

25% Off | Newman Center for the Performing Arts

The Newman Center offers two Director’s Choice packages, DC5 and DC9, each good for a handpicked selection of either five or nine shows (performances can include theater, dance, music, and more)—at a savings of 25 percent. newmancenterpresents.com

Acting Strangely

The story behind one of Denver’s most unpredictable performing arts groups.—Luc Hatlestad

For more than 15 years, the five members of Buntport Theater Company—(from left) Erik Edborg, Erin Rollman, Brian Colonna, Hannah Duggan, and Samantha Schmitz (all Colorado College alums)—have been finishing each other’s thoughts, sentences, and projects. The zany, highbrow troupe is known for creating such original, absurdist gems as Titus Andronicus the Musical and Kafka on Ice. We asked three of them to talk about their origins, process, and the endless search for funny.

Brian: “Buntport” is nonsense, a made-up word.

Brian: We made a version of Don Quixote in the summer of 1999 when we were in college, and it grew out of that.

Brian: There was never an idea that we’d be a theater company.

Brian: Other local theater professionals didn’t believe original work would fly in Denver, but they weren’t underestimating us as much as they were underestimating the town.

Erin: Everyone does everything, including building sets, performing, writing grants, and taking out the trash.

Erin: First, we present ideas to each other. It’s excruciating. We sarcastic clap afterward, and everyone wants to work on his or her own ideas, not anyone else’s.

Brian: We narrow the ideas down into something we can agree on and start writing. We share [the script] multiple times until it’s good enough for rehearsal.

Erin: We’d never say the way we work is better than traditional theater; it’s just the way we function.

Erin: Our process can be faster because we have this finely tuned system and don’t have to consult with outside directors or writers, but it can be slower because no one’s in charge.

Brian: Sometimes you long for that voice.

Erin: We require our audience to work, in a good way. If you aren’t willing to use your imagination, you won’t enjoy it.

Erin: We take our work very seriously and ourselves not seriously at all.

Erin: We have a reputation for being improvisational, but almost everything we do is scripted or planned.

Erik: “Funny” is everywhere. It could happen from a single idea, or it could be more philosophical.

Erin: We thought only diehard Buntport fans would like Tommy Lee Jones Goes to Opera Alone [which is being revived this season] because it was so weird, but it became the best-selling show we’ve done.

Brian: We have a magical life: People give us money to make up shows. That’s an imaginary job. It’s something to be thankful for.

Coming up: Buntport’s first show this season, Naughty Bits (which runs through October 4), follows three storylines based around a statue of Hercules.

Young Blood

Theater has historically appealed to an older demographic; these companies are looking to change that. —JWJ

»The Catamounts

thecatamounts.org

What They’re Doing: This eight-person Boulder troupe performs regional premiere productions—and pairs them with included-in-the-ticket-price specialty cocktails. At its seasonal Feed events, the company puts on themed shows at farms or breweries while the audience enjoys four-course meals.

Who’s Attending: Expect half the audience to be younger than 40—and to not have seen that fabulous production of Hamlet regular theatergoers are raving about.

You’re Paying: $20 to $35 ($70 for a Feed show)

»Off-Center @ The Jones

denveroffcenter.org

What They’re Doing: Tucked behind downtown’s performing arts complex is one of the city’s best-kept theater secrets. Off-Center produces a handful of quirky, often improvised shows that require audience participation. With 200 seats surrounding the ground-level stage on three sides, Off-Center feels more like a casual night out than a formal evening at the theater.

Who’s Attending: Quirky groups of friends and couples hungry for offbeat theater without the caviar.

You’re Paying: Up to $45

»The LIDA Project

lida.org

What They’re Doing: No theater companies have succeeded in the experimental realm quite like the LIDA Project. A collective of actors who have an affinity for new media, this small group of performers at Work|Space Theater has challenged the structure and presentation of performance art for nearly 20 years, often by integrating video, audio, and lighting systems.

Who’s Attending: The intellectually curious and artistically inclined.

You’re Paying: $10 to $25

Role Play

Most people seeking the spotlight head for New York City or Hollywood. But 47-year-old Boulder native Erik Sandvold has fared just fine in Colorado. From playing principal Lloyd Crowder in Plainsong with the Denver Center Theatre Company to narrating more than 1,200 books for the Library of Congress (including the Harry Potter series), the Curious Theatre artistic council member and father of two doesn’t have too much trouble staying busy. We caught up with Sandvold to chat about movies versus theater and his techniques for memorizing lines. —Jessica Farmwald

How did you decide on acting as a career?

I’ve always been interested in many different things, and I realized that if you’re studying theater, you’re studying all of life. There’s history, literature, physiology, music, psychology—all that stuff.

Did you always want to do live theater over movies?

I suppose when starting out, you always hope, Hey, I’ll be a movie or TV star. But I love stage work; it’s so collaborative. It’s wonderful to get the instantaneous feedback from an audience. With my girls growing up and leaving home, though, I’m starting to ask myself about the sustainability of a career in a market this size. I vary from working 39 hours a week to 70 hours a week [including book narration and commercial projects] to make this work.

What’s it like to audition?

It progresses as you spend more time in a market. When I first got here, I was scouring the big newspapers every Friday for audition announcements. You sign up for an audition slot and find out what you need to prepare, which is usually one or two short monologues. It’s been a long time since I’ve had to go in and just do a monologue. It’s not that much fun; that’s the most naked part of being an actor.

Any tricks for memorizing your lines once you get a part?

I like to say things out loud so there’s muscle memory. Sometimes, your mind honestly doesn’t think of it, but your body remembers it and your mouth will say the words even though your brain doesn’t know what they are, which is pretty amazing. You want to get it off the page and into your body as quickly as possible.

You do different voices when you narrate. Which voice character is your favorite?

That’s sort of the thing I’m most known for, doing all these voices. I think Dolores Umbridge, from Harry Potter. It is such a nasty voice—so saccharine and condescending. And I like my Dumbledore. And Voldermort—it’s fun to play villains.

5280.com Exclusive: Read our extended Q&A with Sandvold below.

What should people know about theater in Denver?

The theater scene is better than it should be for its size. It’s this gem Denver has that so many people aren’t aware of. We’re just trying so hard in the theater world to bridge that gap. People react well to personalities, and it’s so easy with sports figures or newscasters. I think if people can start to feel like they know theater people in town, then those actors become a draw. There’s something that’s really valuable to actually having people watch your work over a couple of decades. There’s this whole vocabulary you have together as audience and performer, a shared history. It’s one reason why I’ve chosen to remain in one place and find it so enriching and rewarding.

Do you end up competing against the same people over and over again for work?

Somewhat, but I’m lucky in that I really like a lot of the guys; I think we all kind of are rooting for each other. I feel the competition a little bit more in the commercial industry than I do in theater. In commercial work—industrial films, training videos, little Internet things, legitimate commercials—your track record isn’t going to get you very far. The people casting those things just want who’s best for the particular vision they have. It’s good money, and it’s also more arbitrary.

How else do you make ends meet?

I’ve narrated books on tape for the blind and physically handicapped for almost three decades. It’s been a wonderful baseline of flexible but consistent work that smooths out the ebbs and flows of this line of work, which can be pretty tricky if you’re just holding your breath for the next acting or commercial job.

What happens when a director and actor interpret a scene or role differently?

People may be surprised to know how collaborative it is. I think there’s still a little bit of a Hollywood mystique of the director sitting there calling the shots, and it’s so rarely like that. It’s almost like there’s this puzzle everybody’s trying to solve together in the most elegant way possible. There can be a line where there’s too much contribution from an actor; the director’s already been thinking about it longer than you. But it’s a very respectful thing, usually.

How has the Denver theater scene changed in your time here?

It’s gone through several phases of growth and contraction, which are pretty natural self-adjustments. Over the whole period of the ’90s, I saw a rather steady growth—growth in quality, growth in depth, growth in artistic ambition. And then all the sudden, there were all these companies. I think the real insiders might know it’s nothealthy, but the people who just kind of pay attention to theater think it’s reallyhealthy. You would go see shows during that phase, and you’d see two really good performances and a few that really weren’t acceptable because there just weren’t enough actors at that caliber to fill the roles. There’s an amazing breadth of stuff going on in Colorado, and there’s a lot of quality here as well, but it’s this fragile balance a market this size walks.

Where are we right now?

I really do feel this is a critical time for the performing arts in Colorado. I mean that both negatively and positively. We’re teetering on the edge of something. If we’re able to get the necessary support at this time, I think we’re actually going to make a pretty huge splash on a lot of levels, including nationally. On the other hand, a lot of times when places are trying to take that next step, if the support isn’t there at that moment, the aspirations die away. I think that’s a possibility in the next few years also.

Skilled Set

After honing their talents on Denver stages, these actors, directors, and producers headed for brighter lights. —Justin De La Rosa

1988: Actress Melissa Benoist—who later performs at Littleton’s Town Hall Arts Center—is born.

Today: She’s enjoying success as newcomer Marley Rose on Glee.

1991: Tom Szentgyorgyi begins a five-year stint as associate artistic director of the Denver Center Theatre Company (DCTC).

Today: He writes and works as a producer on CBS crime drama The Mentalist.

1995: Annette Bening—who briefly performed in Pygmalion and The Cherry Orchard with the DCTC in the mid-1980s—stars in beloved political rom-com The American President.

1995: Annette Bening—who briefly performed in Pygmalion and The Cherry Orchard with the DCTC in the mid-1980s—stars in beloved political rom-com The American President.

Today: Like most actors, she found her way to New York City, where she recently performed onstage in Shakespeare’s King Lear.

1996: John Cameron Mitchell plays the role of Peter Pan for the DCTC.

1996: John Cameron Mitchell plays the role of Peter Pan for the DCTC.

Today: Cameron—best known for dreaming up and producing Hedwig and the Angry Inch for the stage and the big screen—had a role as David Pressler-Goings on HBO’s Girls.

2009: Actress AnnaSophia Robb, age 15, receives the Rising Star Award at Starz Denver Film Festival.

2009: Actress AnnaSophia Robb, age 15, receives the Rising Star Award at Starz Denver Film Festival.

Today: The Arapahoe High School grad has three films in production, including Jack of the Red Hearts.

2010: Actor and comedian Rob Gleeson graduates from the University of Denver with numerous open-mic nights at the Squire Lounge under his belt.

Today: Gleeson, now based in Los Angeles, has a recurring role on House of Lies.

Behind The Curtain

Six folks with out-of-the-spotlight jobs that can make a show succeed—or stumble. —Kasey Cordell

Beki Pineda

Owner, All Propped Up

Job Description: Pineda’s Denver company provides anything that anyone might hold, carry, or use during a production.

Trade Secret: Inside one of Pineda’s three warehouses is a complete Forever Plaid kit. For a props person, the off-Broadway musical can be a nightmare because of all the items characters pull out of their suitcases to accompany the songs: a ukulele, a Hula-Hoop, a whip, hand puppets, even an accordion. Pineda keeps it all together in one place so it’s ready to go.

In Her Words: “I usually rent a cargo van to deliver props for two or three shows in one day. I loaded a refrigerator by myself once. But I’m 75 now, so I’m probably going to have to change my work model.”

Andrew Metzroth

Production Manager, Boulder Ensemble Theatre Company

Job Description: Metzroth oversees the artistic design staff and crew (costume, set, sound, and lighting) and often crafts the lighting and sound for productions.

Trade Secret: In last winter’s Annapurna, one scene involved a character putting groceries away in a specific order and making a sandwich. Metzroth and his team had to ensure the grocery bags were in the right sequence onstage and that the bag containing the vegetables had them in the right order—because you can’t stop a show for 45 seconds while the actor looks for an avocado.

In His Words: “My choices come down to creating an aesthetic moment—like if you’re in the forest, how light might filter through trees—and making sure I don’t blow the theater up.”

Joey Wishnia

Dialect Coach/Actor

Job Description: Wishnia works with actors (often his fellow cast members) to create passable accents for various plays.

Trade Secret: Oftentimes the key to English and American accents, according to the South Africa–born Wishnia, is the A’s, R’s, and T’s. In Britain, the A’s are softer: “Can’t” sounds closer to “font” than “ant.” The British also tend to drop the R at the ends of words such as mother, while Americans like to ditch the T sound in many words (for instance, when we say “writing,” it’s not always obvious if that involves a horse or a letter).

In His Words: “I just fell into this. I was doing My Fair Lady, and the accents are so important in that show. I’ve had a good ear since I was a child, and I picked up accents easily.”

Debbie Stark

Choreographer, Phamaly Theatre Company

Job Description: Stark creates the choreography for Phamaly, then teaches it to the actors, all of whom have disabilities.

Trade Secret: Stark’s biggest challenge is understanding each performer’s disability well enough to know how it will affect his or her performance. To do so, she sits in wheelchairs and scooters to see how they move. She’ll have blind cast members touch her as she works through a series of movements.

In Her Words: “Everyone says, ‘You can do shows anywhere and it would be so much easier; why do you do this?’ And I say to them, ‘Because when you’re working with Phamaly, you’re working with people who aren’t worried about how many lines they have or if they’ll be featured. They just want to be there.’ ”

Kurt van Raden

Stage Manager, Denver Center Theatre Company

Job Description: During rehearsals and preproduction, the stage manager communicates the needs of the director and the creative team to the cast, composer, and playwright. During the show, he or she cues actors, music, sound, lighting, and the stage crew.

Trade Secret: During each production, there are two stage managers: one “on deck” who oversees the actors and puts out any fires, and one who cues the technical teams. Van Raden was on deck for 1001 at Space Theater when an actor went on in the wrong direction. Fortunately, the actors were able to cover for the error by rearranging themselves onstage, and Van Raden altered how others entered. No one in the audience seemed to notice.

In His Words: “Being a stage manager is like being a flight control operator: You’re always on the edge of your seat and watching 60 different things so it looks seamless, when you know it could have been a big mess.”

Markas Henry

Scenic and Costume Designer, Curious Theatre Company

Job Description: Henry is responsible for crafting the physical look of the play.

Trade Secret: Henry’s work starts months ahead of opening night when he meets with the entire creative team to discuss what kind of world they want to build. From there, he creates a series of sketches and floor plans. His favorite part is one of the final steps: set dressing. This involves selecting (or making) things like the pictures and paintings that hang on the walls and the rugs—all of the little bits and pieces that bring a world to life.

In His Words: “The most challenging play I’ve done was David Edgar’s Pentecost. Throughout the play we learn that there is this important fresco hidden behind a wall. First we see them taking bricks off the wall to expose it. In the next scene, the brick wall is completely gone. In the next, the fresco is wrapped as they’re restoring it. And at the end, the wall is exploded!”

5280.com Exclusive: Two more interesting theater jobs.

Kevin Copenhaver

Costume Designer, Denver Center Theatre Company

Job Description: Copenhaver conceives, sketches, designs, or buys all of the costumes for a production; he also manages a team that includes the draper (pattern maker), stitchers, and tailor.

Trade Secret: Copenhaver is acclaimed for his work, especially when it comes to period costumes (such as last seasons’s Animal Crackers). He takes regular trips to Los Angeles fabric shops—where there’s a greater selection—to find the materials he needs for such productions. When appropriate, he’ll purchase fully made outfits, as with this fall’s Lord of the Flies. At press time, Copenhaver was seriously considering purchasing real British school uniforms (in grown-up sizes for the adult cast).

In His Words: “We have thousands of pieces on-site. We store them by type and period, like women’s dresses from 1890 to 1920, so we can go into a particular storage room and go through the aisle. We don’t really rent or sell much. In the 24 years I’ve been here, we’ve cleaned out the closet and had just two sales.”

Meghan Markiewicz

Prop Shop Supervisor, Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities

Job Description: Markiewicz is responsible for building, buying, or renting everything the cast interacts with in a show (with a team of two), plus managing the props department’s budget (around $1,000 per production).

Trade Secret: Part of the fun of Markiewicz’s job is doing the historical research to find out what things might have looked like for period pieces—and then determining how to recreate them for the stage. The Great Gatsby, for instance, called for a 1920s gas pump, a huge collector’s item that costs thousands of dollars. Instead, her prop team created one using Denver City sewer pipe and sprinkler parts.

In Her Words: “For Man of La Mancha, which is set in a dungeon in the Inquisition, the set designer wanted big iron lanterns that hung from the ceiling. We bought eight 2.5-gallon tubs of cheese puffs from Sam’s Club for $6 each, cut off the ends, and used fun foam to make the cross pattern, then tissue paper and glue to make aged glass. We ate cheese puffs for weeks.”

5280.com Exclusive:

Peak Productions

The high country is more than just an outdoor playground. Proof: these four high-elevation theaters. —Drew Grossman

Lake Dillon Theatre Company

There’s a reason Lake Dillon Theatre Company is referred to as the most intimate professional theater in the state of Colorado: No audience member—between 52 and 70 people can fit into the black box theater, depending on its configuration—is ever more than 10 feet from the stage. Starting October 10, catch the regional premiere ofThe Mountaintop, a fictional depiction of Martin Luther King Jr.’s final night. 176 Lake Dillon Drive, Dillon, 970-513-1151, lakedillontheatre.org

Breckenridge Backstage Theatre

Over 40 years of curtain raises, Breckenridge Backstage Theatre has transformed from a little-known 74-seat theater with a tiny stage (it began operations out of Singin’ Saddie’s Saloon in 1974) into a Colorado Theatre Guild Outstanding Theatre Award winner. A $1.9 million expansion expected to commence in mid-2015 will include a new rigging system for the stage crew, additional seating, and a redesigned (and larger) lobby. Head west for the regional premiere of Dog Park: The Musical, opening November 25. 121 S. Ridge St., Breckenridge, 970-453-0199, backstagetheatre.org

Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre

Theater can transpire anywhere—even in a log cabin–esque building on the main strip of quaint Grand Lake. But don’t let the classic mountain look fool you: Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre’s 300-seat facility is state of the art (think: a brand-new projector and extensive sound system). Although the venue will be dark this winter (aside from a holiday show on December 1; the new season begins in June), add RMRT to next summer’s vacation plans. This past July, it won the Outstanding Regional Theater award from the Colorado Theater Guild. 800 Grand Ave., Grand Lake, 970-627-3421, rockymountainrep.com

Creede Repertory Theater

The 1930s movie house that serves as Creede Repertory Theater’s main stage has seen it all: floods, fires, and more than a few renovations. That endurance and malleability is echoed by the company as the actors regularly play multiple roles in productions. Stop in for a show at 9,000 feet—the season runs May through September—and be sure to schedule a backstage tour for an extra two bucks. If you can’t wait for season 49, see the company perform rom-com The Last Romance at the Arvada Center through October 26. 124 N. Main St., Creede, 719-658-2540, creederep.org

Money Talks

How much does a show cost? Two area theaters—Lone Tree, a nonprofit arts center that receives city funds, and Dangerous, a single-owner, community operation—open their books. —Mary Clare Fischer

Shows To Know

Get these fall performances on your calendar. —J. Wesley Judd

Dylan Went Electric

Through October 19

Denver playwright Josh Hartwell’s latest explores the tumultuous 1960s.

An onstage bar will be open to patrons during intermission. Miners Alley Playhouse, Golden, minersalley.com

Over the River and Through the Woods

October 3 to 26

Nick’s grandparents don’t understand why he’s leaving New Jersey for a job in Seattle—and they do everything they can to stop him from going. Cherry Creek Theater Company, cherrycreektheater.org

Ambition Facing West

October 9 to November 2

A family struggles—from Croatia to Wyoming to Japan—to outrun its past. Presented by Boulder Ensemble Theatre Company at Dairy Center for the Arts, Boulder, boulderensembletheatre.org, thedairy.org

Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike

October 10 to November 16

This 2013 Tony Award–winner is about a family thrown into upheaval when one sister returns home. Ricketson Theatre, denvercenter.org

Vox Phamalia

October 16 to 26

Edith Weiss’ award-winning sketch comedy series explores the absurdities of living with disabilities. Phamaly Theatre Company, phamaly.org

Guys & Dolls In-Concert

October 22 to 26

A special showing of the classic American musical includes a full orchestra and select dialogue. Lone Tree Arts Center, lonetreeartscenter.org

Legacy of Light

October 24 to 26; October 29 to November 2

The lives of two female scientists, living hundreds of years apart, are juxtaposed in this thought-provoking comedy. University Theatre, Boulder, theatredance.colorado.edu/events

Lucky Me

October 25 to December 6

In this world premiere about love, aging, and airport security, Sara Fine learns that sometimes happiness is about relishing the little things. Curious Theatre, curioustheatre.org

Kindertransport

October 30 to December 7

This play profiles a child who was part of the British government’s Kindertransport rescue mission during WWII. Presented by Theatre Or at Pluss Theatre, theatreor.com

Mummenschanz

November 8 and 9

This unusual theater group uses masks, props, slights of hand, and optical illusions to baffle audiences. Newman Center for the Performing Arts, newmancenterpresents.com

Fully Committed

November 21 to December 28

Sam Peliczowski answers calls at a five-star New York City restaurant. The twist: A single actor plays Sam, the maître d’, the chef, and the parade of callers. Aurora Fox, aurorafoxartscenter.org

She Loves Me

November 25 to December 21

This holiday story, set in the 1930s, follows two parfumerie clerks who despise each other but are, unknowingly, romantic pen pals. Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities, arvadacenter.org

Santa’s Big Red Sack

November 28 to December 21

Santa, carolling, reindeer—no part of Christmas is safe during this raunchy night out (leave the kids at home). Avenue Theater, avenuetheater.com

Miss Saigon

December 5 to February 1, 2015

The Les Misérables team also wrote the score for this tale of doomed romance during the Vietnam War. Vintage Theatre, vintagetheatre.com

—From top: iStock; Courtesy of Michael Mallard; courtesy of Jim Debell; Courtesy of Michael Ensminger; Courtesy of DenverMind Media; Seating Diagrams by Sean Parsons; iStock; Courtesy of Erin Preston; iStock; Courtesy of Alana Rothstein; Courtesy of Wikipedia; Courtesy of iStock; Courtesy Matt Nager; Courtesy of Maeve Wenglewick; Courtesy of Danny Lam