The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Yes, rivers are high. Yes, you can light campfires again. And yes, for the first time in nearly two years, no part of Colorado is experiencing drought conditions. So, can we finally stop worrying about water scarcity?

According to experts, the answer is no.

Though 2019 has brought deep snowpack and heavy rain, we’re still in the midst of a 19-year drought that threatens waterways, landscapes, and communities throughout the West.

“It’s easy to think in a wet year like this that things are better,” says Bart Miller, healthy rivers program director for Boulder-based Western Resource Advocates. “But, in fact, it’s just one wet year—and it doesn’t resolve the long-term trend.”

The long-term trend is this: Since the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) introduced the U.S. Drought Monitor in 2000, Colorado has been bone dry. There have been a handful of wet years, but Colorado has been in a near-constant state of drought—including almost eight straight years from 2001 to 2009. As a result, what’s happened downstream from Colorado has put the entire region in peril.

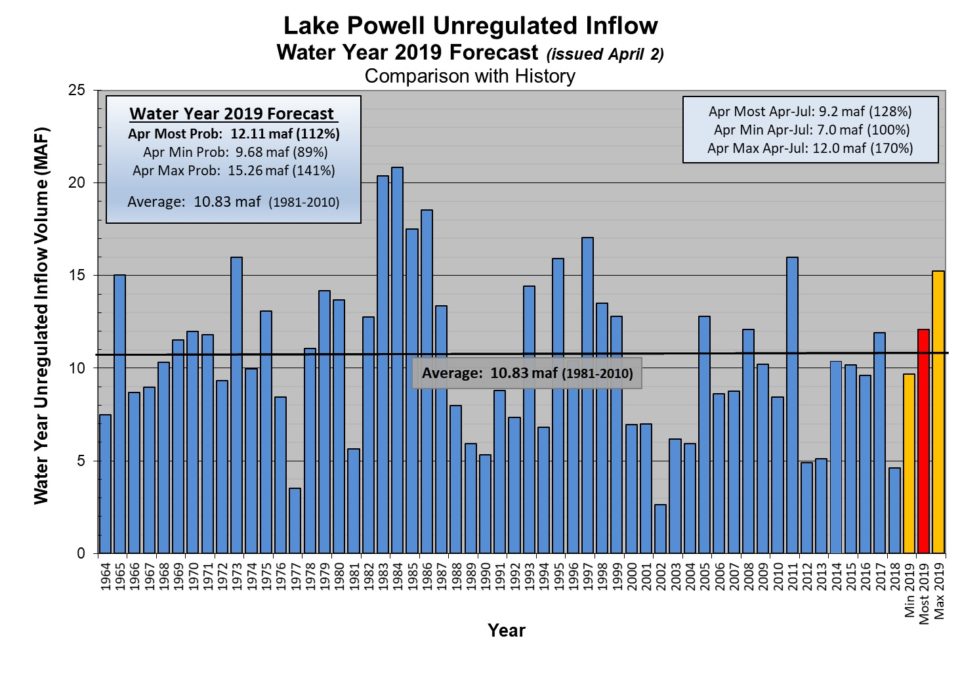

The clearest way to quantify southwestern drought is by measuring the amount of water the Colorado River supplies south to Lake Powell and Lake Mead—the two largest reservoirs for the seven states that rely on Rocky Mountain snowpack. Since 2000, only four years (2005, 2008, 2011, and 2017) have delivered above-average water levels to Lake Powell—which historically has seen an average inflow of 10.83 million-acre-feet per year.

In 2018, for instance, the Colorado River sent fewer than 5 million-acre-feet to Lake Powell. In 2002, the river delivered fewer than 3 million-acre-feet.

If 2019 projections hold, it will be just the fifth year in two decades that the Colorado River sends normal water levels to reservoirs downstream. And while some might think 2019 would bring us back from the brink of crisis, it’s just a blip on a hydrograph when placed in broader context.

“It definitely helps. We’ll take all the water we can get,” says Megan Holcomb, water supply planning program manager for the State of Colorado. “But we would need another 10 years of average or above average [water inflow] to balance what we’ve seen.”

The most significant challenge, though, might be educating the public. According to water scientists, it’s difficult to rally people around water conservation in years when the rivers flow high, the hills are green, and it seems as though if anything we have too much water. Experts say the sense of urgency should be the same as it was in 2018, when much of Colorado was burning, but years like 2019 distract from the larger trend throughout the southwest.

“While a high-water year is great, I’m certainly concerned we lose momentum,” says Matt Rice, Colorado River Basin director for American Rivers. “From a public policy perspective, these high-water years are not helpful.”

According to Holcomb, one way water managers try to alter public perception is by changing vocabulary. Rather than referring to the past two decades as a “drought”—which implies a temporary stretch of dry weather—she uses the term “long-term aridification,” or the process of a region becoming increasingly dry.

Rice, too, stresses that Colorado is in the midst of a “new normal” rather than prolonged drought.

“We’re going to get outlier years like this, but we’re seeing over a pretty significant timescale now that our water availability is diminishing,” he says. “This is the driest 20 years we’ve had in recorded history. One year does not change that.”

Recent efforts have tried to address both scarcity and public perception. The Colorado Water Plan, a strategy instituted in 2015, now serves as a planning document for water conservation across the state. And in March of this year, the seven states in the Colorado River basin (including Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California) approved a long-term drought contingency plan, in which communities voluntarily use less water in order to avoid crisis. Most recently, a group of nonprofit, city, and state leaders launched the “For the Love of Colorado” educational campaign at the Outdoor Retailer Show in June. The campaign intends to inform individuals in communities across Colorado about how they can be more water conscious as the state’s population soars and the climate grows more arid.

For the campaign to be successful, though, it will have to overcome a massive knowledge gap in Colorado at a time when many people can’t clearly see the impacts of drought.

“We need significantly more public awareness,” Rice says. “Ranchers on the West Slope understand the issue. But your average, everyday person on the Front Range does not.”