The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

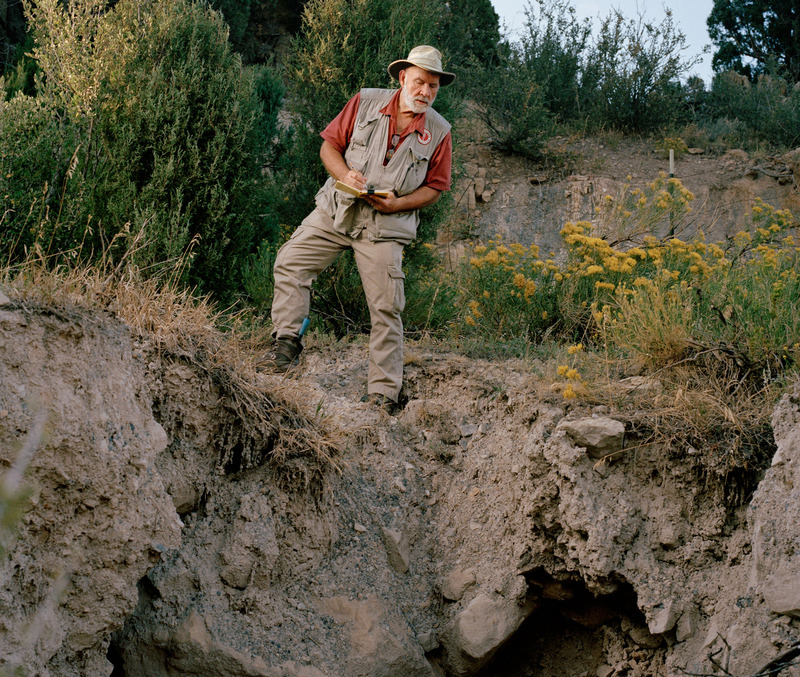

After a cemetery crew removed the casket on a chilly, cloudless morning this past spring, a 62-year-old geologist named Jim Reed lowered himself into the empty, five-foot-deep grave, dropped to a crouch, and began digging. Dressed in jeans, a green shirt, and a vest, with a hat pulled over his thinning gray hair, he carefully scraped away layers of earth with a hand shovel while police investigators watched from the grass above. After several hours, Reed was certain a body had been hidden below him.

Cramped inside the rectangular grave, Reed worked alongside his colleagues, a retired Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI) agent named Tom Griffin and Diane France, a forensic anthropologist from Fort Collins. Together, the trio comprise part of a Colorado-based nonprofit called NecroSearch, a consortium of scientific and law-enforcement experts that has become the country’s preeminent group when it comes to unearthing and identifying human remains.

In this case, the team had been contacted to help find the body of a woman named Kristina Tournai Sandoval. In 1995, the 23-year-old nurse was reported missing after leaving work early to meet her soon-to-be ex-husband, John Sandoval, to settle an IRS debt she’d paid. Greeley police had involved NecroSearch in the case since the late 2000s. Twice, members of the organization were called in to search, but their efforts had turned up nothing.

John Sandoval initially served six years, starting in 1996, for criminal trespassing in relation to his wife’s disappearance. He was convicted of first-degree murder for her death in 2010, though that conviction had later been overturned on appeal. Facing the prospect of a lengthy trial, prosecutors offered Sandoval—who was 52 and looking at spending the rest of his life in prison—a deal. If he admitted to the murder and told authorities where he’d hidden his wife’s body, they’d agree to a second-degree murder conviction that guaranteed his eventual release. This past March, Sandoval told prosecutors about a place called Sunset Memorial Gardens in Greeley.

France received the call from the Weld County District Attorney’s office after Sandoval’s disclosure. Among her many duties as NecroSearch’s president, France weeds through dozens of formal law-enforcement requests before sending them to members to determine if they can help. She’d been intimately involved in the Tournai Sandoval case since the first search, and now it had finally broken open. Not only had Sandoval implicated himself, but he’d also told investigators about the general area where he’d buried his wife: an open grave near a tree, across from a dirt road. Police investigators had already narrowed down the possible site to three plots, all of which were filled the day after Tournai Sandoval’s disappearance in the summer of 1995. Of those three, the DA said, one seemed to match Sandoval’s recollection. The grave belonged to a World War II veteran. Although prosecutors were determined to find the body, they hoped to minimize both the financial burden—exhuming a casket can cost tens of thousands of dollars—and the psychological drain on everyone involved, especially the families.

At around 8 a.m. on March 23—six days after what would have been Tournai Sandoval’s 45th birthday—cemetery workers dug into the ground with a backhoe. They removed the sod, then dug through two feet of sandy clay and into gravel farther below. The workers pulled off the concrete casing over the casket with a large metal chain attached to the backhoe. Then they began to lift the metal box from its hole. “After 22 years, there was only the slightest bit of rust on the handles,” Reed told me recently. The workers removed three small cylindrical disks and a concrete plate at the bottom of the grave. “Just like that, they whisked the casket away,” Reed said. “Then it was time to work.”

After Reed eased himself into the grave, an investigator handed him a large metal box, a piece of ground-penetrating radar equipment that’s used to send sonic waves into the dirt. The box had an antenna and a chain Reed used to drag the device across the ground. He made three passes while Griffin checked the thin waves that appeared like an EKG on a screen set at eye level atop the grass. After the third pass, Griffin beckoned France, Reed, and several investigators to look at the monitor. “We definitely have an anomaly under here,” Reed said.

France jumped into the grave and began scraping dirt in one corner, where the anomaly was most pronounced. Reed and Griffin, along with an assistant coroner, got to work in the middle of the grave. After an hour or so, Reed and Griffin took a break. France kept digging. “Diane wouldn’t stop,” Reed said. “I tried to tell her she needed to rest, but she refused. She was determined to get to that body.”

As France pulled away the dirt, she spoke in calm tones and always referred to the potential remains as “Tina” or with the gendered pronouns “she” and “her.” After two hours of digging, at about 20 inches below the original grave’s floor, France finally hit a black tarp. She carefully scraped away more dirt. Slowly, a human outline began to reveal itself. “Tina was lying on her left side, with her head to the south in a half-curled fetal position,” Reed said.

Once the dirt was completely cleared from the body, the tarp—which was wrapped in several places with duct tape—was carefully lifted from the grave with cloth straps, then placed atop another tarp under a large tent. The coroner arrived and cut open a piece of the tarp that was wrapped around the remains. Beneath that was a blanket, and under that was a body. Within minutes, the remains had been loaded into a van and taken to the coroner’s office; the original casket was returned to its grave. France and Griffin packed their equipment in their cars and quietly congratulated each other. Reed lit a cigar and walked alone through the cemetery. Then they all went home, knowing it wouldn’t be long before they got the next call.

Human beings have been killing one another for as long as they’ve been on Earth. The story of Abel’s death at the hands of his brother is told in the Book of Genesis. Ancient papyrus revealed a murder plot against Egyptian king Ramesses III, who probably had his throat slashed in 1155 B.C. Four years ago, researchers in the Atapuerca Mountains of northern Spain discovered 52 broken pieces of a 430,000-year-old Neanderthal skull. When they reconstructed the fossilized bits left behind in an underground cave system, scientists discovered two “penetrating lesions” above the left eye, likely caused by repeated blows from a single instrument. “This finding,” researchers concluded in the scientific journal PLOS One, “shows that…lethal interpersonal violence is an ancient human behavior.”

Earlier this year, I’d been told about NecroSearch by a local prosecutor who’d occasionally enlisted the group in cold-case jobs. Body hunting is a strange business: Looking for remains is time-consuming and costly, not to mention emotionally exhausting for anyone associated with the case. Even the best-prepared plans often don’t pan out. Prison snitches are unreliable, as are distant memories of long-ago events. Once-abandoned fields become strip malls. Buildings are torn down and scraped away. The earth erodes and remakes itself. Animals scavenge.

NecroSearch’s members have achieved a level of success unmatched anywhere in the world; they are so respected that even their unsuccessful searches are deemed significant. Or, as the prosecutor explained to me, “If you want to search for a body in a certain place, and those people don’t find it, that means a body probably isn’t there.”

Sometime around the Tournai Sandoval discovery this year in Greeley, NecroSearch volunteers descended on a landfill in Arapahoe County to look for the remains of a woman who’d been missing for nearly two years. (In addition to a forensic specialist, geologists, a search-and-rescue dog handler, botanists, a human tracker, and many other positions, NecroSearch counts one of the nation’s few landfill-search authorities among its ranks, which are spread across the country.) After running computer models on the site, the expert—a retired police officer from Abilene, Texas, named Lee Reed—was confident he could pinpoint the exact location of garbage collected at the time of the woman’s disappearance.

Authorities used a backhoe, rakes, and gloved hands on a section of trash that had been mashed to the consistency of concrete. “We put the backhoe in and hit right in the middle of the dates we were looking for,” Lee Reed told me. And they made a relevant discovery. (Investigators declined to further describe what was found because the case is ongoing.)

Curious about the group’s work, I arranged to meet France this past summer at her office. She made time for me a few weeks before departing for Europe, where she was going to work as part of an academic group, led by the University of Wisconsin and sponsored by the Department of Defense, that would recover and identify the remains of an American pilot shot down during World War II in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of northern France. The remains eventually would be released to the pilot’s family for burial.

France’s office is in an industrial park in Fort Collins. She makes polyurethane-based plastic casts there as part of a business she started in the early 1980s. France sold the operation to an employee in 2011 but stayed on, creating detailed molds and casts of everything from a Bengal tiger’s tongue to the amputated tibia of a Civil War general who’d lost his leg during the Battle of Gettysburg. The delicate, repetitive work—setting casts, then sanding and painting them—gives France a distraction from the more gruesome details of her day-to-day workload. “After a while, everyone needs an escape,” one NecroSearch member told me, “especially Diane.”

She was standing inside the front door when she introduced herself. Sixty-three years old, France is petite, with blond hair. She has strikingly fine features, high cheekbones, and a narrow nose. Her eyes are the color of worn quarters. France has a hint of a country drawl, which, considering her line of work, brings to mind Jodi Foster’s character, Clarice Starling, in Silence of the Lambs. Over the course of her 30 years at NecroSearch, France’s plainspokenness has become legend among her friends. “If you’re digging and Diane says she’ll kill you if you accidentally stick a probe through a skull,” Jim Reed told me, “you believe her.”

France wasted little time before leading me down a short hallway and into a brightly lit room where dozens of manufactured skulls were stacked neatly atop sinking wooden shelves. Some of the skulls had gunshot holes in their foreheads. “Pretty interesting, isn’t it?” she said.

At the time of our meeting, France had been NecroSearch’s president for two years, running the nonprofit and figuring out how to coordinate cases on a miniscule budget for a group that relies entirely on volunteers. She’s something of a celebrity in her field, as one of around 100 certified forensic pathologists worldwide—and one of few women in the male-dominated profession. She has been part of many major disaster-response teams across the country, work that has sent her to identify remains of 9/11 victims in New York City and to a hillside in Guam where a Korean Air flight crashed and 228 people died. She’s the director of the Human Identification Laboratory of Colorado, and she’s lectured and written several books on the subject.

During her time with NecroSearch, France has been intimately involved in a couple hundred murder cases. “Diane’s seen more awful things than all of us combined,” said Clark Davenport, one of NecroSearch’s first members and one of France’s closest friends. “Mentally, physically, emotionally, she’s one of the toughest people I’ve ever known.” France admitted her work can be grisly, but she said the disturbing feelings are overridden, at least some of the time, by the sense she can do something to ease a family’s burden. “Every time we exhume a body, we’re helping someone, somewhere,” she told me. “Some people give to the United Way. I give my time here.”

France grew up in the 1950s and ’60s in the small town of Walden, a speck on the map near the Wyoming border. An inquisitive student, she decided early that she’d eventually make her livelihood in science, which delighted her father, David France, the town doctor. France began her life in anthropology as a student at Colorado State University, where she’d eventually do graduate work at the school’s Human Identification Lab, taking apart and putting together human remains. Despite the nastiness of the work—she once had to soak a severed head in warm water to remove the flesh, muscle, and tendons—she became fascinated with the clues a body could leave behind. A puncture wound or a microscopic cut on bone was more than bodily damage. In the right interpretive hands, it could become a road map that led beyond the manner of death and into the human psyche, into something far more sinister.

By the time she’d completed her Ph.D. in anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder in 1983—under the tutelage of Alice M. Brues, one of the field’s female pioneers—France was running her casting business and selling full-size skeletons and other items to medical schools and laboratories. After graduating, France received an invitation to join the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, a major honor. She returned to CSU as an affiliate assistant professor and later became the director of the identification lab.

Just before Christmas in 1985, the coroner in Glenwood Springs asked France for help identifying 12 victims who’d died in a gas-plant explosion. When she arrived, France realized it was just her. Victims were battered and blown apart, many of them burned beyond recognition. Almost immediately, emotions roiled inside her. “It was a defining moment,” she said. She had an epiphany. “I decided I needed to take all those things I was feeling, put them in a box with a bow around it, and put that box on a shelf in my mind,” France told me. “I had to separate emotion from the science.” She worked two straight days to identify the victims, pulling remains out of body bags stored inside the morgue cooler. When she was done, she turned them over to the coroner for burial. “And then,” she said, “I went on with my life.”

Inside the back room, France grabbed one of the skulls she had made from a real-life original. It had a small hole in the back and a much larger one in the forehead with exposed jagged shards. The work was remarkably lifelike. “Fifteen year old,” France said. “Execution-style. Back of the head.” She held up another skull, with damage that looked similar. Another gunshot? “Blunt trauma,” she said, pointing to a crushed area just above the left eye socket.

She then placed the skull back on the shelf and began pulling out a series of cast bones: a femur, a hip, a mandible. The originals belonged to an elderly woman we’ll call Mrs. H. As a directive from Mrs. H, the woman’s remains were initially given to a Texas body farm, much like the one made famous by crime writer Patricia Cornwell. After decomposing for two years in Texas, Mrs. H’s remains were shipped to the office in Fort Collins. Even after studying tens of thousands of bones in her lifetime, France still views each as a small biological wonder. In this case, Mrs. H had a titanium rod screwed into her femur to stabilize a long-ago break. Smooth, white bone had grown over it like a blob of vanilla pudding. The woman’s body was trying to make itself whole again. Mrs. H had significant osteoporosis, evidenced by two broken hips and bone-on-bone wear in her knees. Based on this, I wondered aloud if Mrs. H had been in agony toward the end of her life. France shrugged. “If she’d been living with it for a long time, maybe she got used to it,” France said. “You’d be amazed how much pain we can absorb if it’s always there.”

In the past three decades, NecroSearch has helped police and district attorneys with more than 300 cases in 40 states and on four continents. Fifteen bodies have been discovered as a result of that work. They’ve been found in mine shafts and in landfills, hidden under a pile of rocks in the Rocky Mountains, and buried under a suburban patio in Arizona. Once, a victim was discovered stuffed inside the trunk of a car that had been dumped into the Missouri River. Another time, a body was tangled in a Northern California redwood’s root system. When a Tennessee suspect learned authorities enlisted NecroSearch to find his missing wife, the man referred to the group as a bunch of “high-tech witch doctors.”

A few months ago, Clark Davenport met me at a bookstore in downtown Denver. The 75-year-old geophysicist was a few weeks from leaving for Russia on a NecroSearch-approved trip during which he would help look for the remains of Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, the youngest brother of Tsar Nicholas II. The two men—along with Nicholas’ wife, Alexandra, and three daughters—famously had been murdered and buried in clandestine graves by Bolshevik rebels a year after the February Revolution in 1917. With the rest of the murdered Romanovs discovered in the early 1990s, finding the grand duke was considered the last piece of a historical puzzle. The trip would be Davenport’s fifth to Russia in the past decade. It was work that filled him with excitement and gave him a much-needed respite from the dozen or so ongoing, more pressing NecroSearch cases in which he was involved.

Despite the underlying enthusiasm about his upcoming trip, Davenport was in a solemn mood. He was dressed for a funeral, wearing a black suit jacket and trousers with a pressed white dress shirt and a red bow tie. His close friend Vickey Trammell, a soft-spoken botanist, community college instructor, and former NecroSearch board member, had recently died of what her colleagues believe were complications from Parkinson’s disease. Trammell’s work had been essential in several cases, especially her expertise in identifying growth patterns of plants and cut roots to help determine a grave’s age.

The work had been a calling card for the group, as was Davenport’s use of ground-penetrating radar, in 1994, to help police in Phoenix locate the remains of a woman whose husband killed and buried her nearly three decades earlier. With Trammell’s passing, that all seemed like a long time ago. “You wonder how many years you’ve got left,” he said. Along with the deep sadness he felt over the loss of his friend, Davenport was also melancholy over the future of the group he’d been involved with for so long. Or, as he put it, “None of us has plans to get younger.”

In the past several years, four current or former NecroSearch members have died, including Al Bieber, an expert on using sonar and lasers to investigate potential gravesites, and Jack Swanburg, a former police investigator and the man responsible for bringing France aboard following her work in the Glenwood Springs gas-explosion case. Swanburg and Davenport had worked closely over the decades (they’d initially met when Davenport was called to do ground-radar work for CBI), and the two helped create a facility in Douglas County that used dead, buried pigs—rather than humans—to study graves and how their surroundings evolve over time. Sitting at a table in the bookstore this past summer, Davenport said the recent deaths had become a reminder of NecroSearch’s fragility, and of the changes happening within their group.

For the most part, NecroSearch has shunned publicity. Its 40-plus volunteers meet formally 10 to 11 times a year, plus the time they spend working together on cases. Their work for law enforcement is almost entirely pro bono—search costs can exceed $100,000 for less than a week of work—and reimbursements generally only include travel, hotels, and meals. “We like learning, and we like helping,” said Reed, who co-owns a geology software firm in Golden and is responsible for the largest talc-deposit discovery in the United States. “We don’t do this for recognition; we’re not looking for attention.”

The team includes a laboratory coordinator from the Colorado School of Mines who’s developing plans for a robotic device that can detect decomposing flesh. Two botanists from Fort Collins have done work studying pollen left behind in air filters as a way to determine where a suspect may have driven to dump a body. And there’s Davenport and Reed, who’ve spent decades refining ground-penetrating radar.

The organization’s members have always preferred to do the bulk of their work in private. NecroSearch’s home base is located at the Highlands Ranch Law Enforcement Training Facility in Douglas County, but there aren’t paid employees, and no one works in the office. Phone calls go directly to voicemail. Members rarely discuss their work. At any one time, the group might be working a dozen or more cases—all of them initiated by law enforcement or district attorneys’ offices across the country. On rare occasions when they talk about what they do, members are reluctant to accept credit. “You can’t have a good search without good police work beforehand,” Davenport said. “The groundwork is already there; the investigations are done by the time we arrive.”

That isn’t to say people aren’t trying to bring NecroSearch into the spotlight. The group has received requests, which they’ve so far turned down, from independent video-production companies about doing a reality show. “I think we have to be open to new things,” said Bruce Yoshioka, a 51-year-old Colorado School of Mines laboratory coordinator who’s been a NecroSearch member for the past three years and voted in favor of having cameras follow the group. Still, he admitted he has reservations. “I want people to know who we are so we can help more of them, but I also don’t want to lose the foundation this thing was built on,” he said. “I don’t want us to be distracted from the mission, because the mission will always be the most important thing.”

Davenport understands Yoshioka’s point. “We’ve been faced with this issue for years now, and it’s time we did something about it,” he told me. “This was a small group when it began; then we became a nonprofit, and we had police from all over the world asking for our help. Now we have to figure out what comes next. Do we take on even more cases? Can we? How do we get smart, younger people to volunteer when they’re building their own careers? How do you tell someone they’re going to invest huge amounts of time and emotion and their own money into something that will never pay them financially? I don’t know that any of us have the answers.”

He looked at his watch. He’d been talking for nearly an hour. “I have to get going,” Davenport said.

We shook hands. Trammell’s death and NecroSearch’s challenges had Davenport contemplating his own mortality, he admitted. Before we parted, he had a question. He sheepishly asked if I would help him write his obituary. “I’m not sure my family understands half the stuff I’ve done, or what NecroSearch has done,” he said. “I just want to make sure they know.”

After putting the cast replicas of Mrs. H’s bones back on the shelf, France returned to an office up front. To preserve the integrity of her evidentiary work in cases where she may be called to testify at court, France has two rooms upstairs that are protected by heavy, locked doors. Both rooms are off-limits. “Not even my husband has been in there,” she said. The room up front has two windows overlooking a small parking lot. Along the walls are all manners of ephemera: a large microscope, drill bits, dozens more cast skulls, and a recently created cast of a fin whale’s brain. In one corner is an articulated skeleton that once hung in France’s father’s office in Walden.

A large table in the middle of the room is covered with a white cloth. When she recreates human structures, she sometimes spreads the bones there. After France completed Mrs. H’s skeleton, she invited the woman’s daughter to the office. France described the work she’d done, then offered to show the woman photos of her mother’s bones. After the daughter saw the photographs, France asked if she wanted to see the real thing. When the woman agreed, France opened the door to the front room. “It was a very personal, very intimate moment,” France remembered. “It was kind of beautiful.”

Not long after she began her work with NecroSearch, France started having a recurring nightmare. Night after night, a killer would chase her through a building. The man was fast, but France always managed to keep a step ahead, though she never could actually get away. As she ran up the stairs and through the shadowed hallways, France would recognize the building as one of her old grade-school classrooms back home in Walden. For what felt like hours, she’d run through the building, trying to stay alive.

After the terrorist attacks in New York City on September 11, 2001, France was part of a team that was dispatched to the city to identify human remains. She was put on duty in the unfortunately named Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island, surrounded by a square mile of 20- to 30-foot-tall piles of crushed concrete and metal that once had been part of Lower Manhattan. “There’s no way you can forget the enormity of that,” she said. For two straight weeks, France and a graduate student were shown pieces of what looked to be human remains. “Sometimes it was just bones from restaurants,” said France, who worked alongside the FBI and Secret Service. It was her job to make a definitive determination. Shortly after she returned home to her husband in Fort Collins, she realized the nightmares had stopped.

This past year, however, France’s closest friends have begun worrying about the toll her life’s work has taken on her. “I really believe she has PTSD,” Davenport told me. “Personally, I’m not interested in knowing about the victim or what happened when they died. Diane wants to know everything. She’s meticulous in that way. She cares about every detail.”

“I will think about all of this forever,” France told me as she sat in a chair inside her front office. She was squeezing a miniature foam brain of an orangutan like a stress ball. “I’ve seen too much to forget,” she said. “How can you not have trauma when you do what I do? There will come a time when I have to say I’m done.”

France contracts with the Larimer County coroner’s office to do casework. “I feel like they’re giving me the horrible ones,” she said. She offered a forced smile that implied she wasn’t kidding. Recent NecroSearch cases, too, have seemed exceedingly violent to her. The murders these days are “on a scale that I’ve not witnessed before. The sheer violence seems so much more intense. The brutality….” She paused for a moment and looked at the ceiling, as if she were recalling cases in her mind. “The brutality of the crimes is different than before. It’s not enough to simply kill a person. Now you have to stab them and shoot them and run them over and take them apart and burn them.” (When I told France’s colleagues about her observation, they seemed surprised their friend would make such a declaration. “I don’t think what we’ve seen is any different than what’s been going on at any other time in history,” Reed said.)

France shifted in her chair. “There was this case,” she began. Her face went blank, as if she were in a trance. “This child,” she finally said, almost in a whisper. It was from four or five years ago. “It was the worst case of my life.” France attended the autopsy. “I always wonder what the end was like,” she said.

Then, seemingly contradicting herself, she added, “But if I focus on the brutality, I wouldn’t be able to do this. What would I be doing to help society? What would I be doing to help these families? What would I be doing for justice? I’ve seen things people shouldn’t see, but that’s the relationship I’ve made with death. I’ve taken tragedy and made it part of my life.” I wanted to ask for more details about the child’s case, but watching her sit there, it seemed inappropriate, like tearing deeper into an already open wound.

Instead, I tried to change the subject. I told her it was good her nightmares had finally stopped. She turned to face me and grimaced. She shook her head and said, “I’m having them again.”

At John Sandoval’s sentencing a week after they’d recovered Kristina Tournai Sandoval’s body, France, Reed, and Griffin sat in the back of a Greeley courtroom surrounded by investigators who’d spent the better part of their careers working to solve the Tournai Sandoval case. The three had been invited by the city’s police department, something of a thank-you for the work they’d done. As the three sat quietly, they could see Tournai Sandoval’s family up front, near the prosecutors. When Sandoval was sentenced to 25 years in prison, plus five years of parole, he betrayed no emotion. He is scheduled to be released in 2042, when he’s 77 years old.

After the sentencing, in front of scribbling journalists and rolling television cameras, Kristina Tournai Sandoval’s sister’s father-in-law thanked police and prosecutors. He thanked the city for its support. Then he thanked NecroSearch for its work. Reed, who stood off to one side with his team, gave a solemn smile to his friends. After the media scattered, Tournai Sandoval’s family introduced themselves to the trio. They shook hands and offered their gratitude. They were finally able to close this chapter of their lives.

After Tournai Sandoval disappeared in October 1995, her family bought a granite gravestone and had it placed in a cemetery in Windsor. On it, they had her name, the words “In Loving Memory,” and a single rose engraved. A photo of Tournai Sandoval—with long hair and soft features—was stamped into the rock, a frozen moment of confident, youthful beauty. Her closed lips show off a relaxed, self-assured smile. Her dark eyes stare into the distance.

Tournai Sandoval’s parents received her remains shortly after the NecroSearch discovery. They had their girl at last. They went to the cemetery and hosted a private ceremony with family and close friends. Twenty-two years after she’d gone missing, they finally buried their daughter’s remains in the plot with a view of the Rocky Mountains.