The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Seconds after the Denver Broncos defeated the Carolina Panthers in Super Bowl 50, gold confetti burst out of cannons and fluttered high above the turf at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California. Amid a celebratory buzz that reverberated all the way to the Rocky Mountains, photographers and TV cameramen swarmed Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning, who had finally won a second championship two months shy of his 40th birthday. With more than 100 million people watching, CBS sideline reporter Tracy Wolfson asked Manning the one question on everyone’s minds: Was he going to retire? In his brief response, the Louisiana native veered from the topic of football and said something so jarring you could almost hear the record scratch.

While the Broncos battled the Panthers on the field that night, another war was being waged at the Super Bowl, this one over the future of a $22 billion industry almost as sacred to Colorado as football: craft beer. Perhaps clueless to the cosmic significance, Manning told Wolfson that he would take time to reflect before deciding on retirement; he said he first planned to kiss his wife and kids and then added, with a wry smile, “I’m going to drink a lot of Budweiser tonight, Tracy, I promise you that.” A few minutes later, during the presentation of the Vince Lombardi Trophy, Manning again plugged the self-anointed King of Beers.

Considering that the Super Bowl is often the most-watched television event of the year, during which 30-second commercial slots cost as much as $5 million, one marketing consultant declared Manning’s Budweiser name drops “probably the most valuable endorsement in history.” Problem was, in that moment, draped in a Broncos jersey, Manning stood as a symbol of Colorado, a place full of people who proudly declare the Front Range the Napa Valley of Beer. But it wasn’t just that Manning had touted a lager brewed by a giant corporate beer company on national television; what twisted the knife particularly deep was that he touted a lager brewed by that giant corporate beer company.

Over the past decade, sales of mass-market light American lagers have dipped about one percent each year. At the same time, craft beer sales have grown around 13 percent annually. By the end of 2015, craft accounted for just over 12 percent of the total market, and some projections indicate that figure could climb as high as 25 percent in the next 10 years. Business being business, big beer companies have not only noticed, they’ve reacted—none more so than the world’s largest brewer, Belgium-based Anheuser-Busch InBev (AB InBev), which boasts a portfolio of popular brands including Budweiser, Bud Light, Rolling Rock, and Stella Artois. (Anheuser-Busch still operates as a wholly owned subsidiary of AB InBev and is headquartered in St. Louis.)

Most notably, in 2011 Anheuser-Busch began purchasing craft breweries such as Chicago’s Goose Island and folding them into a new division of the company called the High End. Caught off guard, beer connoisseurs were left to wonder what it meant that Goliath had just bought David. Those acquisitions have continued, and in March Anheuser-Busch finalized the purchase of its first Colorado outfit: Breckenridge Brewery. Local brewers were dismayed by the announcement, describing the Breck sale as having created “a disturbance in the force” and saying that it felt like “losing a member of the family.”

The King of Beers has also taken the fight to the pricey Super Bowl airwaves. This year, the company produced two commercials designed to take on small independent brewers. In the first, Budweiser seemingly mocks craft beer drinkers by championing its own bigness. One scene shows a gruff older man flicking an orange wedge from the rim of his beer glass after text flashes on the screen: “Not a fruit cup.” Paradoxically, the company also advertised its Belgian white beer Shock Top, which is designed to attract craft beer drinkers and is almost always served with an orange slice. In fact, the beer’s label depicts an orange wedge wearing sunglasses. “Craft beer is affecting big beer,” says Colorado Brewers Guild marketing director Steve Kurowski, “and big beer is affecting little beer.”

In the days after the Super Bowl, reporters and bloggers speculated as to whether Anheuser-Busch had paid Manning to mention its beers in prime time. A company spokesperson tweeted that although they were delighted he’d done so, they had not offered Manning any money. (At least one media outlet reported that Manning owns a portion of two Anheuser-Busch distribution companies in Louisiana.) Looking for a way to spin the incident, Julia Herz, program director for the Boulder-based nonprofit Brewers Association, had two packages with 10 craft beers each sent to Manning a couple of days after the big game. She included a letter that congratulated the quarterback and noted that the Brewers Association thought these beers might “satisfy the celebratory occasion more than a light American lager from a large global brewing conglomerate.”

Turns out, not only had someone else already had the same idea, they were quicker to react. In a nod to the fact that Manning’s team had just won Super Bowl 50, Anheuser-Busch sent 50 cases of Budweiser to the Broncos’ after-party, at which the game’s MVP Von Miller put on a show rapping alongside Lil Wayne. As for the 20 craft beers—it’s unclear if they were ever opened.

On a cold Friday afternoon in early March, Charlie Gottenkieny, a sizable 66-year-old man with a gray goatee and a gentle demeanor, reached into the front pocket of his pressed khakis. In one fluid motion, he extracted a bottle opener and popped open a bomber of beer called Jagged Twilight. He poured samples and passed them around to his business partner, 37-year-old Ryan Evans, and three lenders from Citywide Banks, all of whom had gathered in a dusty, unfinished commercial building on the outskirts of northwest Denver. The space was still weeks, if not months, from being finished, but the fact that the bank had loaned Gottenkieny and Evans several hundred thousand dollars had less to do with wooden beams and concrete and more to do with what was in the glasses they’d just been handed.

Depending on how you count, this project was almost five years in the making—ever since the day in late 2011 when Evans and his wife took a class at Colorado Free University called the “World of Belgian Beer.” Gottenkieny taught the course; he gave an overview of Belgium’s rich brewing history—a passion of his—and talked everyone through samples of 16 different styles of Belgian beer. Every so often, Gottenkieny would bring along a few of his Belgian homebrews and offer to share them after class. Evans and his wife gladly accepted and were surprised when they liked Gottenkieny’s beers better than any of the commercial stuff they’d sampled. That evening, Evans wrote down his cell number, gave it to Gottenkieny, and said to give him a call if he ever wanted to start a brewery.

At the time, Gottenkieny was already considering a move to Southern California to open a brewery with a close friend who lived there. But the funding for that project evaporated several months later. Gottenkieny abandoned the idea—and called Evans. The two drafted a business plan and began meeting with banks about financing. After six months of rejections, they sat down with Citywide Banks, the Aurora institution that partially financed Avery Brewing Co.’s massive expansion in 2015. Finally, someone agreed to take a chance on them.

By the end of 2012, Evans and Gottenkieny shifted their focus to finding a location. They looked at several warehouses in the RiNo neighborhood and quickly realized that Colorado’s marijuana industry had begun to drastically alter Denver’s commercial real estate market. In some cases, buildings were leasing to grow houses at a price per square foot that was four times what Gottenkieny and Evans had budgeted. They expanded their search radius and visited a small commercial strip in a new development just north of I-76. Although the location seemed a little out there, the building was brand-new, which meant it had proper gas and water lines, sufficient electricity capabilities, and a good HVAC system—necessities that could easily cost $200,000 to upgrade in an old RiNo warehouse.

The pair signed a lease on December 19, 2014, and shifted their focus once more. Gottenkieny brainstormed a lineup of Belgian beers. They hired an architect and added to their stockpile of secondhand brewing equipment, which already included Black Shirt Brewing Co.’s old four-barrel system. Construction on the brewery started a year later, in the middle of December 2015—four years after Evans and Gottenkieny first met and about three years after deciding to go into business together.

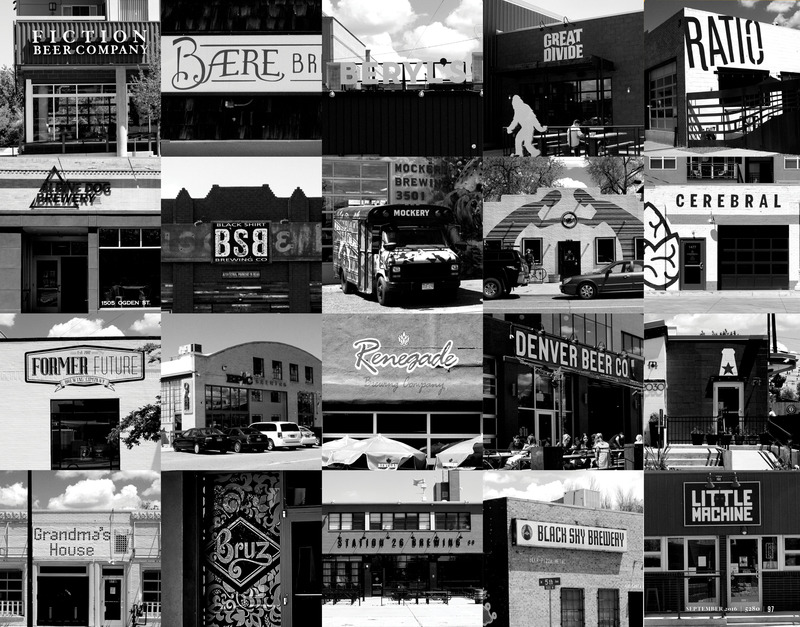

In that time, the beer industry had undergone a seismic shift. At the beginning of 2011, there were 13 breweries in Denver; by the end of 2015, there were 53. Statewide, during the same span, that number jumped from 126 to 284; only California and Washington have more breweries than Colorado. Big beer companies such as Anheuser-Busch had also joined the craft world, purchasing small, independent breweries in beer-centric regions such as Seattle and Denver. Simply put, Evans and Gottenkieny were about to enter a rapidly growing and competitive industry in one of the hottest craft markets in the country—a fact that was on the mind of at least one of the lenders that day in March.

Evans kicked off that meeting by walking everyone around the space. He pointed out a few changes they’d made to reduce costs: No fancy bar countertop. No fireplace. He explained that barring any hiccups, the contractor was on pace for a final inspection on April 22. After the tour, everyone drifted toward a makeshift table by the front door where Gottenkieny had stashed a few bombers, including the Belgian quadruple called Jagged Twilight, the first batch of beer he’d brewed specifically for this project.

While they all drank, one of the lenders told a story about having opened a security business in Texas. At the time, he said, the industry was extremely competitive. But he said that was a good thing, a signal there was demand in the market—all you had to do was be in the top 10 percent. That, the lender explained, was precisely why he felt good about bankrolling this project: Gottenkieny was already one of the most decorated homebrewers in the country.

Beer has always been a competitive industry, dating back to the formation of the modern era of brewing in the 19th century. Until recently, the American high point by at least one measure came in 1873, the same year Adolph Coors opened a brewery in Golden. There were 4,131 breweries in the United States that year, a record that would stand for well over a century. The vast majority of those places were small and locally focused. During the next several decades, however, larger breweries were aided by advancements in pasteurization techniques, the addition of cold storage to railcars, and the advent of national marketing. As a result, bigger operations thrived, and the industry began a trend of contraction and consolidation. By 1918, only about 1,000 breweries remained, and when the clock ticked to midnight on January 16, 1920, those that were left were forced into the shadows.

The 18th Amendment prohibited “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” Although notoriously difficult to enforce, Prohibition remained in effect for the next 13 years, until Congress repealed the law when it passed the 21st Amendment. Breweries quickly reopened—756 within the first year. But the initial boom was short-lived; a few years later, canned beer became popular, and small breweries that couldn’t afford the expenses of packaging and distribution shuttered by the dozens.

By 1978, the number of breweries in the United States hit an all-time low; there were around 50 operating fewer than 100 facilities, and just six companies—Anheuser-Busch, Miller, Heileman, Stroh, Coors, and Pabst—controlled 92 percent of the market. A well-known British journalist who covered beer observed at the time that most of these breweries produced similar products: “They are pale lager beers vaguely of the pilsener style but lighter in body, notably lacking hop character, and generally bland in palate. They do not all taste exactly the same but the differences between them are often of minor consequence.”

Just as diversity in the beer industry bottomed out, a 17-year-old kid named Eric Wallace moved with his family from Germany to Las Vegas. Wallace, who would go on to co-found Longmont’s Left Hand Brewing Company, had grown up overseas because his father was in the Air Force. Even at 17, Wallace was used to drinking good German beer; after his high school soccer matches, if the team had played well, the coach would buy everyone a round. Wallace says he’ll never forget the moment he first walked into a Las Vegas convenience store looking for a six-pack, never mind that he wasn’t of legal drinking age. He remembers thinking, Wait a minute, where’s the good beer? It’s all the same. “I lived in the wealthiest nation,” he says, “and the manliest beers had all been watered down.”

After almost 60 years of breweries disappearing and flavor flatlining, the line on the graph turned up again. The 1980s marked the beginning of a microbrewing renaissance that is in many ways the foundation of today’s rich craft beer culture. New Albion Brewing Company in Sonoma, California, is widely considered the country’s first craft brewery. New Albion inspired other classic craft brands still around today, including Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. in Chico, California, and Colorado’s Boulder Beer Company. In 1982, homebrewer Charlie Papazian celebrated the new microbrew movement by hosting what he called the Great American Beer Festival in Boulder. (The festival moved to Denver two years later to expand.) The Mile High City got its first brewpub—Wynkoop Brewing Company, co-founded by now Governor John Hickenlooper—in 1988. Many of Colorado’s most iconic breweries, including New Belgium Brewing Company, Great Divide Brewing Co., Avery, and Wallace’s Left Hand, were founded in the early ’90s. By 1994, craft breweries accounted for one percent of the country’s total beer market.

Fast-forward another two decades to December 2015, and the number of breweries in the country reached 4,144, finally surpassing the old record from 1873. Just as it was back then, most are small and locally focused—96 percent produce less than 15,000 barrels of beer a year. And there are roughly 1,800 U.S. breweries currently in the planning stages. Still, it’s difficult to predict which direction the industry will head next. Julia Herz of the Brewers Association gets asked all the time whether craft breweries are nearing a saturation point. “I think it’s the wrong question,” Herz says. “There are 8,000 wineries; I never see that brought up. If you took the population levels of the 1880s and compared them to today, the United States could support 30,000 breweries.”

Wallace, on the other hand, who has been a vocal opponent of what he describes as the recent “re-homogenization of the beer universe,” believes that at least along the Front Range, the industry is headed for another period of contraction. “The landscape is going to look radically different in five years,” he says. “The failure rate was so low in the last decade that anybody could start a brewery and be successful. That’s about to change.”

Throughout his 20s and 30s, living in Washington, D.C., and Dallas, Charlie Gottenkieny was a Miller Lite drinker. Plain and simple. So it’s no surprise that when he boarded a plane in 1988 in Texas and settled in for the 10-hour flight to Brussels, Belgium, a country known for its complex ales originally brewed by Trappist monks, the trip had nothing to do with beer—at least not at first.

Gottenkieny traveled often for his job. He worked as an instructor for a company that sold training systems to big, worldwide businesses like Hewlett-Packard. At some point during that lengthy flight across the Atlantic, Gottenkieny reached for the in-flight magazine in the seat-back pocket in front of him. Flipping through the glossy pages, he paused to read a feature article about the very place he was headed. It was all about beer.

That night, when he checked into the airport Sheraton, Gottenkieny noticed a lobby bar that specialized in Belgian beer. Intrigued after having read the magazine story, he settled into his room and then returned to the main floor and struck up a conversation with the bartender. Gottenkieny tried a variety of Belgian styles—saisons, tripels, dubbels—all for the first time. He was particularly fascinated by a specific type of slightly sour beer known as a lambic. At first, the bartender refused to serve him one, figuring he wouldn’t like it; as far as he knew, Americans only drank light lagers. But Gottenkieny insisted, assuring the bartender he’d pay for the drink whether he liked it or not. “I loved it,” he says. Four hours later, happily buzzed, Gottenkieny stumbled back to his room.

He stopped into the hotel bar again each night that week. He also ventured to different restaurants and beer bars around the city. By the time Gottenkieny boarded his return flight, after only a week in the country, Belgium had sufficiently kicked his Miller Lite habit.

His whirlwind introduction to good beer continued as soon as his plane landed. On his way back to Dallas, he’d scheduled a long layover in D.C. so he could spend time with his brother. While the two visited that night, his brother served him a beer that tasted a lot like the brews he’d just been drinking in Belgium. When Gottenkieny asked what it was, his brother explained that he’d made it himself. Gottenkieny had no idea it was possible to make good beer in your kitchen. He was so excited that he coaxed his brother into showing him how to brew a batch that night.

Gottenkieny was hooked. He returned to Dallas the next day, looked up the closest homebrewing store, and purchased everything he needed to brew his first solo batch. He quickly taught himself more advanced homebrewing techniques and joined the North Texas Homebrewers Association. Eventually, Gottenkieny entered his beer into homebrewing competitions. He did pretty well. As of today, Gottenkieny, who moved to Denver in 2009, has earned more than 100 medals for his beers. In January 2013, his Winter Solstice Saison won best in show at the prestigious Big Beers, Belgians, and Barleywines festival in Vail. And he’s the only person ever to win the American Homebrewers Association Homebrewer of the Year award twice. The beers that earned him that honor? Both lambics.

Over the years, Gottenkieny furthered his beer knowledge during subsequent trips to Germany and England, but Belgian beer always remained his favorite. “I just love them. I love the variety of flavors and the spirit of Belgian brewing,” he says. “It’s all about the creativity involved, but it’s controlled creativity. There’s always a theme to it, and there’s a harmony in it; it’s all about balance.” When Gottenkieny began to think about opening a brewery—first in California and then in Denver—there was no question it would be Belgian-focused. He thinks specializing in Belgians will help give him and Evans an edge in the current competitive market. “I think it’s going to be harder for a brewery that’s a generalist,” he says, “[a place] that has a standard slate of an IPA, a pale ale, and a stout.”

Beyond that, he and Evans are focused on quality. He visits some Front Range breweries today and can tell they’re cutting corners; for example, using the same yeast for every beer—which is less expensive than running through multiple strains but can result in a lineup of beers that all have similar tastes—or brewing with a fruit extract instead of fresh fruit. And although Gottenkieny sees no use in naming names, he says some breweries around town have developed a reputation for never dumping a batch of beer, no matter how poorly it turns out. For their part, Evans and Gottenkieny are focused on the long term, which they believe means producing a high-quality product no matter the cost. “The reason is,” Gottenkieny says, “there’s a shakeout coming.”

If you’re looking for the epicenter of the future of Colorado craft beer, Denver’s RiNo neighborhood is a good place to start. The microhood has become the Mile High City’s unofficial brewing district, with at least eight breweries within 15 blocks. There are mainstays such as Black Shirt, Our Mutual Friend Brewing, and Crooked Stave Artisan Beer Project; there are newcomers like Beryl’s Beer Co. and Ratio Beerworks; and in summer 2015, Denver beer titan Great Divide opened the first phase of a large expansion project on Brighton Boulevard. But what’s more intriguing is what’s yet to come.

A few blocks north of the Great Divide spot, Chicago-based MillerCoors (a joint venture between Milwaukee’s SABMiller and Denver’s Molson Coors) leased an old warehouse and, in July, opened a 27,000-square-foot Blue Moon Brewery; a grand opening is scheduled for the restaurant and taproom this month. In what now seems like a prescient move, the company launched its Belgian-style witbier in 1995 at a small facility in the newly opened Coors Field stadium. Today, the beer is a popular nationwide brand, sales of which have grown for an unprecedented 81 consecutive quarters. Molson Coors CEO Mark Hunter calls it the “number one craft beer in the United States.”

But last year Blue Moon was also the source of a lawsuit that alleged Miller-Coors has deceived customers by marketing the beer as craft—obscuring the fact that it’s brewed by a large corporation and charging the premium price small craft brands tend to command. That argument, in part, hinges on the Brewers Association’s definition of “craft brewer,” which includes any operation that is producing six million barrels of beer or less annually and are no more than 25 percent owned by a noncraft brewing entity. (MillerCoors brews about 76 million barrels of beer per year.) A San Diego district court judge dismissed the case. Molson Coors’ Hunter says he doesn’t think the definition of craft is all that relevant. “Implying that something up to a particular size is of better quality is just not true,” he says. “Whether it’s large batch or small batch, the craft of brewing is absolutely essential to what we do.”

Anheuser-Busch is also moving in on the opposite end of RiNo, near Coors Field. In January, the company confirmed plans to open a brewpub at 2620 Walnut Street, the former site of Casselman’s Bar & Venue. But there won’t be a Budweiser sign out front. Instead, the marquee will read “10 Barrel Brewing,” an Oregon-based outfit that Anheuser-Busch acquired three years ago. (The company has announced similar plans for a 10 Barrel pub in San Diego.) Patrick Crawford and Charlie Berger, co-founders of Denver Beer Co., which is less than two miles away, worry about what they see as Anheuser-Busch’s tactic of obfuscation, that Coloradans will visit the taproom and not have any idea who owns the place. “That burns me,” Berger says. “I kind of want to buy a building across the street and just paint it to say ‘10 Barrel is owned by Anheuser-Busch.’?”

Oskar Blues Brewery also plans to enter RiNo this year, with a CHUBurger restaurant and beer garden at 35th and Larimer streets. (The company is also eyeing a new music venue and beer bar in LoDo.) The Lyons-based brewery represents another new trend—one that isn’t directly related to big beer but has everything to do with big money. Last summer, owner Dale Katechis, who maxed out a stack of credit cards to launch Oskar Blues in 1997, reportedly sold a controlling stake in the company for an undisclosed sum to Fireman Capital Partners, a private equity firm in Boston. “As craft continues to take market share and grow, the stakes keep getting higher,” says Oskar Blues spokesperson Chad Melis. “We were able to find a fund that is independent and unorthodox—and equally inspired with doing things different and being competitive.” In recent years, in addition to restaurants and bars, Oskar Blues has spun off new business ideas such as cold-brewed coffee and a mountain bike company.

As far as the Brewers Association is concerned, private equity ownership doesn’t impact what makes a craft brewer a craft brewer, so Oskar Blues still counts. But because they’re now owned by big beer companies, breweries like 10 Barrel and Breckenridge no longer meet the requirements. Other recent deals fall into this non-craft category: For instance, Belgian brewer Duvel Moortgat Brewery has acquired Firestone Walker Brewing Company, Boulevard Brewing Company, and Brewery Ommegang; and Constellation Brands, a New York–based beverage company best known for products such as Svedka vodka and Modelo Especial lager, recently paid $1 billion for San Diego’s Ballast Point Brewing & Spirits.

Ask those in the Denver beer community what constitutes craft, however, and you’ll get a variety of answers, regardless of how the Brewers Association defines it. Great Divide owner Brian Dunn believes Breck is still craft. “Some people care, some people don’t,” says Dunn, referring to the technical definition. “The most important part is that the beer is good.” Chris Black, founder of Denver’s Falling Rock Tap House, believes some of the business moves made by Oskar Blues clearly signal that the company should no longer qualify as craft. This summer, Black posted a fiery open letter on his Facebook page explaining why he’d decided to stop carrying Oskar Blues’ beer. Denver Beer Co.’s Berger doesn’t think Breck should qualify as craft, and, somewhat hesitantly, says the same of Oskar Blues. “I hate to say it, though,” Berger says. “We’ve drank their beers for years; Dale’s Pale Ale was one of the two beers at my wedding.”

As a still relatively young brewery looking to expand, Berger and his business partner, Crawford, who just two years ago opened a new $1.7 million canning facility in north Denver, spend a lot of time thinking about this stuff. When I interviewed Crawford and Berger at a table in their Platte Street taphouse this past spring, they explained that education is the foundation of their business, that they hope to spark excitement and loyalty among customers by talking about the smooth flavors that result from aging a barley wine in an oak barrel or why they choose to use rye in their red IPA.

“If we wanted to,” Crawford says, “we could take on a private equity investor—probably tomorrow—get a bunch of money, discount our beer, blow it out all over the state of Colorado for three dollars less a case than we’re selling it right now, and then turn around in six months and sell our brewery to AB—and Charlie and I could retire on a beach very easily. But that’s not our business model.” Berger adds, “I think we’d make a lot of sacrifices to do that.”

Evans got a call in late March from his general contractor, who had bad news. The cold, wet spring had made certain construction tasks impossible to complete without a heated workspace. They couldn’t mud the drywall or paint. Evans had been hounding the landlord for months to install the gas meter and turn on the heat. They lost weeks of work and had to push their grand opening back.

At frustrating times like this, Evans sometimes thinks back to the semester of college when he studied abroad in northern France, which was how he got into all this in the first place. During his junior year, Evans, a Colorado native, hopped a train from the French countryside to Bruges, Belgium, where the owner of the hostel he was staying at offered him a local brew. Evans had never had anything like it. “I couldn’t get enough,” he says. “Next thing you know, I found myself spending weekends up in Belgium every chance I could get.” After graduating college in 2003, Evans moved to the Front Range. He sought out good Belgian beer but didn’t find much of it until a place called the Cheeky Monk Beer Cafe opened on East Colfax Avenue in 2007. (Cheeky Monk closed in July.) As a birthday present several years later, his wife arranged for them to attend that class at Colorado Free University called “The World of Belgian Beer,” where they met Gottenkieny and sampled some of his homebrews.

Now he and Gottenkieny were about to open a Belgian-style brewery together, and the recent construction delay notwithstanding, Evans felt good about their prospects for success. In fact, they’d specifically altered their business model in a way they thought would better fit the current market. Since Colorado liquor laws allow breweries to self-distribute, at first Evans figured they’d spend a lot of money and time on bottling and cart their beer to every restaurant, bar, and liquor store that would take it. But the competition for tap handles and shelf space has become so intense they decided instead to focus on serving good Belgian beer in their taproom.

In Colorado, the production, distribution, and sale of booze is built on what’s known as the “three-tier system.” In theory, each segment operates independently to ensure a fair marketplace; in Colorado and other states, however, there’s a loophole that allows breweries to own distributorships, and last summer Anheuser-Busch bought two well-established Colorado distribution companies. (The company has made similar purchases in California and Oregon.) Uncomfortable with the new owners, many local craft brands, including Odell Brewing Co. and Great Divide, took their business elsewhere. “We felt the focus would be primarily on AB-owned brands first,” says Eric Smith, Odell’s chief sales and marketing officer. “You can make great beer, but if you can’t get it out there, you’re not going to be successful.”

Two months later, Reuters reported that the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) was investigating whether Anheuser-Busch had sought to “curb competition in the beer market by buying distributors, making it hard for fast-growing craft brewers to get their products on store shelves.” That report was followed a day later by news that Anheuser-Busch’s parent company, AB InBev, planned to take over the world’s second-largest brewer, SABMiller, in a proposed $100 billion deal.

The DOJ investigated the merger for possible antitrust violations, and in December, Congress held a subcommittee hearing to examine potential impacts on competition in the beer market. In late July, the DOJ approved the deal, which is expected to be finalized by the end of the year. The arrangement calls for SABMiller to spin off its domestic production to a third company, Denver-based Molson Coors, but gives AB InBev more of a presence in overseas markets such as Africa and Latin America. The decision also puts limits on Anheuser-Busch’s ability to purchase distributors and requires the company to notify the DOJ if it plans to buy a craft brewer.

Still, the bigger Anheuser-Busch gets, the more smaller brewers worry about the company’s ability to impact pricing. Great Divide’s Dunn says he’s already heard of Goose Island kegs selling around town for less than the cost of a local craft keg, which means bars could offer Goose Island IPA on draft and turn a higher profit than they could on, say, a tap handle pouring Great Divide’s Titan. Wit’s End Brewing’s Scott Witsoe has similar concerns. After five years, growth at his Valverde taproom has finally slowed and Witsoe decided to try commercially distributing his beer as a way to grow the business. “The scary thing is,” Witsoe says, “at what point can AB say ‘OK, we have enough craft beer brands established in our portfolio; let’s knock $3 off of all our six-packs’?” (A representative from Anheuser-Busch’s craft division did not respond to multiple requests for an interview or comment for this story.)

What’s more, in June, Governor Hickenlooper signed a bill that will allow grocery stores to slowly expand the number of locations at which they can sell wine and full-strength beer. Hickenlooper said he only put his pen to the legislation to help avoid a ballot measure that would’ve allowed beer at every grocery store in the state overnight. Compromise aside, Witsoe fears the new law could still result in smaller, independent liquor stores closing, thus reducing his options for shelf space in an already crammed market. “There’s so much going on right now,” Witsoe says. “These next few years are going to be this redefinition period of craft beer.”

This past January, for one of the first times in four years, a Front Range brewery closed. The thought of a brewery going out of business in Denver had become almost unthinkable, but after months of slipping sales and a failed attempt at revamping its beer lineup, the owners of four-year-old Arvada Beer Company, located in a historic brick building in Olde Town Arvada, locked the doors. The president of the local business association speculated the brewery “just couldn’t compete in this environment.” In a way, that closure marked the beginning of a series of tumultuous developments in the first half of 2016.

In April, Anheuser-Busch continued on its march of purchasing craft breweries. On the heels of closing the deal with Breckenridge, the company celebrated the acquisition of its eighth craft brewery, Virginia’s Devils Backbone Brewing Company. (The brewery’s owner resigned his position on the Brewers Association’s board of directors, and Devils Backbone’s CEO was replaced as chair of the state’s craft brewers guild.)

In May, Boulder’s Twisted Pine Brewing Company announced the unusual move of ceasing nearly all distribution, a significant shift in the company’s business model. Brewery president Bob Baile said Twisted Pine would instead concentrate on its taproom and a few select draft accounts. “With the landscape of the industry, it’s just crazy,” Baile told the Denver Post at the time of the announcement. “There’s a bazillion breweries out there, and everybody has stuff on the shelves.” Wynkoop made a similar decision a few weeks later.

Then, on June 10, the same day the governor signed the grocery store bill, several breweries announced they were leaving the Colorado Brewers Guild to form a new advocacy organization called Craft Beer Colorado. A letter detailing the move explained that “with the changing landscape of craft where multinational brewers are buying craft brewers and blurring the lines, our by-laws and articles of incorporation don’t reflect what we believe to be membership’s wishes.” Oskar Blues, Great Divide, and Left Hand were among 14 that joined the new group. “The need to adapt and respond to a rapidly changing environment in our industry, including the acquisition of craft brands and distribution rights by global brewers, was a leading motivation in the formation of the organization,” Left Hand spokesperson Emily Armstrong wrote in an email.

Coincidentally, that same day in early June marked a third beer-related event: At 1 p.m., after three weeks of back-and-forth with a building inspector, a final certificate of occupancy was issued for a brewery six miles north of downtown called Bruz Beers. An hour later, Evans and Gottenkieny opened their place to the public. They had a more formal event planned for another day, but they’d been waiting for this moment for so long they figured they’d prop open the doors and see if anybody wandered in. That evening, more than 70 people crowded around the bar ordering pints of Gottenkieny’s Belgian brews.

The name Bruz Beers is sort of an ode to Belgium; it’s meant to evoke the French spelling of Brussels (Bruxelles) and Bruges, the town where Evans sampled his first Belgian beer. But it wasn’t their top choice. “Coming up with a name was a bitch,” Gottenkieny says. They preferred Mountain Monk, but another business had already registered the name. Gottenkieny tried to contact the owners to see if they’d sell the rights but never heard back.

When Bruz opened on June 10, an otherwise unsettling day in the Denver beer world, the competition and chaos didn’t seem to matter all that much. Instead, after more than five years of preparation, Evans and Gottenkieny happily focused on what they’d wanted to do all along: share their passion for good Belgian beer. “I’d rather sell the best beer in the world,” Gottenkieny says, “than the most beer in the world.”