The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

5280.com Exclusive: Read more about the team’s new coach here.

The McGraw Athletic Center on the Colorado State University campus isn’t exactly the awe-inspiring homage to collegiate athletics one might expect. There’s a bronze bust in the compact lobby area that honors Thurman “Fum” McGraw, CSU’s first consensus All-American defensive tackle, who played in the late 1940s. There’s a small glass case with a smattering of trophies and banners. And…that’s about it. Unlike the grand foyers and museum-quality displays in athletic centers at universities such as Louisiana State, Auburn, Clemson, West Virginia, Penn State, Georgia Tech, Michigan, Texas, and my alma mater, the University of Georgia, McGraw is what a lifelong devotee of big-time college sports might politely call understated.

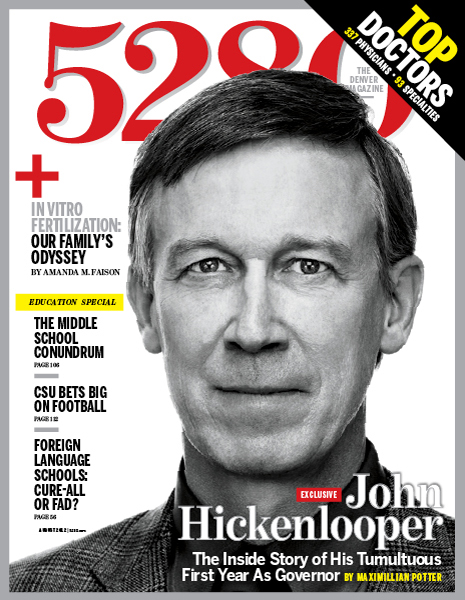

With their prefab desks and green waiting room–style chairs sitting beneath a drop ceiling and poor lighting, the CSU football offices are even more modest. Crowded into one side of the second floor of McGraw, the team’s operational home has all the ambience and mystique of your average high school principal’s office. It’s late March, and I’m here to see CSU’s new head football coach, Jim McElwain. I’ve settled in for a long wait—head coaches are notoriously overscheduled—when his administrative assistant tells me I can go on in to his office. He’s three minutes early.

“Hey, Linz, c’mon in here,” coach McElwain says. I’m not sure how he knows my nickname, or why it seems so natural for him to use it. But it does. It’s almost as if he’s already decided I’m one of the proverbial good ones. I can’t imagine I’ve done anything to win his favor, especially considering that during our initial exchanges I half-jokingly let him know that as a Georgia Bulldog, I’m no fan of his previous employer, the University of Alabama. Even so, Coach Mac, as everyone calls him, is all smiles as I take a seat. He slouches into his chair, runs a hand through his fine brown hair, and throws his feet up on the desk. His white ankles peek out between brown loafers and beige slacks, and it’s obvious he’s not as comfortable in an office, dressed in a navy blue plaid sport coat, as he would be in a sweatshirt and shorts out on the practice field with his players.

Although the athletic department has ordered updated furnishings and a flat-screen TV for his Spartan office, most of it hasn’t arrived yet. McElwain is leaving the decorating decisions to his assistant because he has other concerns—namely, a roster of players that will compete for the distinction of being literally the most physically diminutive team in the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision. He’s also dealing with the fact that he lacks a kicker with enough leg to consistently put the ball in the end zone, he’s short on tight ends and wide receivers, and he’s without an obvious starting quarterback.

All this plainly weighs on McElwain’s mind a short time later as he sits—once again with his feet up, his interlocked hands resting on his head, a pinch of Copenhagen wedged inside his lip—at the head of a conference room table at a Tuesday morning staff meeting. About 18 other coaches crowd into the room, almost all of whom are new to CSU. As a group they run through the team’s personnel position by position with friendly banter and blunt assessments:

That one needs to get his pad level down…. This one can’t catch a cold…. If he can’t advance the ball there’s no sense in having him on the field…. The kid’s good, but he’s lacking focus…. It’s not his fault, it’s his parents’ fault—he can’t help what’s in his genes…. He’s a disappointment to me…. That young man there just isn’t a ballplayer.

These probably aren’t conversations McElwain had very often at Alabama, whose backups could start for many other schools. While the Crimson Tide was running up a 48-6 record during McElwain’s four years as offensive coordinator—a stretch that included a Heisman Trophy–winning running back and two national championships—the CSU Rams were limping their way to 16 wins and 33 losses.

After two hours of conversation, the windowless room begins to feel stale. McElwain is usually a man who smiles easily. He also has an endearing habit of laughing to himself for no apparent reason—as if only he sees the humor in a given situation. Right now, however, he’s not amused. His gold wire–rimmed glasses have slid down his nose, and he can’t stop yawning. He’s been going from coach to coach, explaining what he wants them to do and what he wants to see from their players. He ends almost every directive with the question, “You know what I’m gettin’ at?” Although he asks it rhetorically, it’s not immediately clear that they do.

McElwain would probably say that in his 26 years of coaching, he’s seen worse. But it’s obvious he knows this team likely will suffer through at least one more sub-.500 season—something he hasn’t had to deal with in a long time. He also likely would say that this doesn’t feel like pressure, that real pressure is coaching in front of more than 100,000 crimson-clad fanatics in Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The truth is, though, coach McElwain has simply traded one brand of stress for another. After all, he’s never been a head coach; he’s never had the full responsibility for wins and losses landing solely on him. And he’s definitely never been in a position where creating a winning football program virtually from scratch is being heralded as a way to reinvent an entire university.

On an early May afternoon, CSU’s campus is quiet. Except for a few students who have stuck around for summer session, the sidewalks are empty, the classrooms are dark, and the Oval—the symbolic center of campus—stands stoic in the face of another three-month break. The 583-acre campus sits just southwest of Old Town Fort Collins, where nearly every restaurant, bar, and store features Ram green and gold in its decor. CSU students fill orders at the local ice cream shop and work the registers at Old Town boutiques. Recent grads buy small houses in South College Heights and populate cubicles at Hewlett-Packard.

Without CSU, this small city, population 143,986, might never have grown much beyond the military outpost it began as in 1864. (Colorado wouldn’t become the 38th state until 1876.) Two years before “Camp Collins” was founded, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act, the law that provided grants of public land to establish colleges. Today, there are more than 100 of these “land-grant” institutions throughout the United States and its territories. CSU, which began life in 1879 as Colorado Agricultural College, is the state’s only one.

About 133 years and a few name changes later, the CSU campus bustles with 30,000 students, eight colleges, and 1,540 faculty members, all contributors to the school’s distinct yet somewhat indefinable culture. Despite its local reputation as a haven for stoners and New Belgium beer aficionados, CSU has never appeared in the Princeton Review’s list of the country’s top party schools. It has, however, been ranked by Popular Science as having one of the top 25 “most awesome college labs”; it ranks among the top 15 colleges with undergraduates serving in the Peace Corps; and it’s been lauded by multiple publications for its emphasis on green initiatives and technology. CSU’s College of Agricultural Sciences consistently ranks in the top 10 nationwide for its awards, grants, and contracts. The university is also home to one of the best veterinary medicine programs in the country as well as an elite atmospheric science school. Among universities without medical schools, CSU attracts the second largest amount of research dollars, behind only Georgia Tech.

Accolades like these underline the university’s academic accomplishments, yet there’s a quiet confidence among students and faculty that seems rooted in something else. By almost anyone’s estimation, CSU is the third most-prominent university in the state, behind the University of Colorado Boulder and the Air Force Academy. Maybe the self-assurance comes from the belief that the school is an oft-overlooked gem, a serious college populated with aggies, geeks, and hippies that somehow thrives in relative seclusion without the attention—and scrutiny—that more brand-name universities attract.

The problem is that thriving requires a lot of money. And in the past decade, the state of Colorado has repeatedly cut higher-education funding. In the past three years alone, CSU has lost a cumulative $36 million in state financing; the university’s president, Dr. Tony Frank, expects further cutbacks. To combat this shortfall, in 2011 CSU reluctantly raised student base tuition by 20 percent (a $1,051 increase), a move that runs counter to the land-grant university’s mission of providing affordable access to higher education. The funding dilemma has forced Frank, who has been with the university since 1993 and has served as president for three years, to explore other potential moneymaking endeavors. “I’m a huge fan of land-grant universities,” Frank says. “I think they’re one of the greatest American inventions of all time. But right now, there’s a tremendous challenge to determine what the future of this system is as public funding declines.”

It’s simple, really: Frank needs students—from Colorado, but especially from other states—to want to attend CSU. He wants the words “Colorado State” to roll off high school seniors’ tongues with the same excitement elicited by institutions such as the universities of Texas, Wisconsin, Ohio State, or California-Berkeley—all household-name schools that draw students from beyond their state borders. Hell, he’d like CSU to be thought of before CU-Boulder, which right now sounds a little crazy, if not downright impossible.

Frank knows CSU can compete with many big-brand schools academically. Where the school falls short is outside the classroom. Frank says—and many agree—there’s one department where CSU hasn’t been measuring up for years; an area that’s highly visible, potentially lucrative, and likely to attract higher enrollment. Frank wants CSU’s pitiful football team to find some swagger, start kicking some ass, and make any teenager watching ESPN think longer and harder about Colorado State University.

Even casual sports fans realized CSU outkicked its coverage when it hired Jim McElwain. Local sportswriters didn’t even think to place him on CSU’s short list when the school fired head coach Steve Fairchild after last season, because no one thought a coach with McElwain’s resumé would consider CSU. That sparsely furnished office at the McGraw Athletic Center doesn’t exactly scream “dream job” to a top-tier football coach. CSU’s athletic budget is a paltry $26 million—$33 million less than CU’s and more than $70 million less than that of Alabama, which turned a $40.7 million profit on its football program in the 2010-2011 fiscal year. Given McElwain’s and Alabama’s track record—the Crimson Tide is projected to be a national title contender again this year—he probably could have been a prime candidate for any number of sought-after jobs in 2013.

It’s not as if a winning program attracted McElwain, either. Ram football has cracked the Top 25 just a handful of times in its history. For a few fleeting years in the 1990s, CSU rather inexplicably broke into the national rankings. Then in the early 2000s, head coach Sonny Lubick put the pigskin in a golden-haired boy’s hands and let him loose. Behind quarterback Bradlee Van Pelt, the scramble-first Rams were regulars on ESPN highlight reels, found themselves ranked nationally, and compelled giddy fans to fill the 32,500 seats at Hughes Stadium.

It couldn’t last. Maintaining a winning team on a tiny budget, in the middle of the country, in an old stadium, in the non-Bowl Championship Series (BCS) Mountain West Conference simply wasn’t going to happen without serious support and reinvestment from the university. Lubick, who is too gracious to ever say so candidly, received neither. “We sometimes didn’t have up-to-date video equipment,” he says with a laugh, “which is kinda like an English teacher not having a good textbook. And before [former Ram and NFL linebacker] Joey Porter gave us $250,000 to upgrade the locker room, ours was so outdated that I didn’t even like to bring recruits by there.”

Lubick was making more than $500,000 when he was let go in 2007 and says he and his assistants were among the lower-paid staffs in Division I football. Fairchild was making about $700,000 when he was fired. McElwain earned $510,000 last year as a coordinator at Alabama and likely would command the NCAA Division I average of $1.47 million to become a head football coach. This meant CSU would have to make an unprecedented investment in its football program to even begin to compete.

Frank was willing to do just that. “I became convinced that for us to accomplish what I wanted us to accomplish in athletics, we really needed someone who had a very big vision of what CSU athletics could be,” he says. And so, last December, Frank replaced athletic director Paul Kowalczyk (CSU bought out the $910,000 left on his contract) with Jack Graham, a feisty, retired businessman who played quarterback for the Rams in the early 1970s and had been a donor to CSU athletics. The decision to hire Graham came about organically: CSU’s athletic department needed cash to fund renovations to the university’s Moby Arena, and Frank asked Graham if he was interested in contributing. Graham said no, but instead detailed for Frank his grander plan for CSU athletics, which included higher buyouts for coaches, creative marketing to attract spectators, and, most important, an on-campus football stadium.

Frank thought about how Graham’s business acumen might translate to intercollegiate athletics, and how the former quarterback might energize a department that had lost its verve. He soon went back to Graham: “I think the stadium is an interesting idea,” Frank said, “but I think it’s only a piece of the puzzle. If we want to change the game, I think we need to bring a different culture and a different level of expectations into our athletics programs.” That’s when Frank offered Graham the athletic director job.

Graham started by firing Steve Fairchild, and paying the remaining $350,000 on the coach’s contract. Then for $250,000, Graham hired a New York–based consulting firm to help him find a new head football coach. (It doesn’t take a Ph.D. in mathematics to figure out that CSU spent more than $1.5 million—all from private funds—just to pave a path toward possible football success.) The consultant began with a list of 100 potential coaches and, with Graham’s input, whittled it to 10. At the top was McElwain.

When Graham introduced McElwain as the Rams’ new head coach less than two weeks after assuming the AD job, it was obvious why CSU wanted him. McElwain was a big-name coach from an even bigger-name university that plays in the best college football conference on the planet. (Southeastern Conference teams have won the past six national championships.) What wasn’t as obvious: Besides his $1.35 million contract, why would McElwain want to coach at CSU?

It’s a mid-April evening, and the mood inside the small theater in CSU’s Lory Student Center is congenial and studious, as if a seminar on master gardening or how to install home solar panels is about to begin. More than 300 people—a noticeable majority with graying hair—sit in metal chairs with legal pads and pens at the ready. But this isn’t a lecture; it’s a pep rally. The presenter is Dr. B. David Ridpath, associate professor of sports administration at Ohio University and an expert in issues surrounding intercollegiate athletics. The CSU grad has been asked to speak in Fort Collins by a new organization called Save Our Stadium Hughes (SOSHughes).

Although CSU president Tony Frank and AD Jack Graham—along with McElwain and another recently formed group dubbed Be Bold CSU—believe a strong football program is a smart investment in the university’s future, not everyone in Fort Collins is convinced. In tight economic times, when faculty and staff haven’t received raises in four years, academic programs are incurring cutbacks, and students are facing tuition increases, many see the hearty financial support of athletics as a questionable—and demoralizing—decision. But the biggest point of contention is not the money that has already been spent; it’s the money CSU’s athletic director would like to dole out to replace the aging, off-campus Hughes Stadium with a new on-campus football arena.

Nestled into the foothills four miles from CSU’s campus, Hughes Stadium opened in 1968 as a quaint little field in a bucolic setting. But times have passed it by. In April, Alex Callos, a columnist for bleacherreport.com, ranked all 124 stadiums in Division I football; the venue that SOSHughes is so desperately trying to rescue came in at 119.

Along with Graham, CSU football supporters are proposing a replacement for Hughes that would be built between Pitkin and Lake streets, just blocks from Old Town, and hold approximately 42,000 fans—still minuscule compared to the 100,000-seat behemoths common to the Big Ten, SEC, and Big 12. The new stadium’s $250 million price tag has some folks—including students leery of potential associated fees—balking. Others have different objections: Fort Collins residents fear the hoopla surrounding Saturday football games will create problems with parking, vandalism, and public safety, promote public intoxication, and leave the historic center of town a trashy mess come Sunday mornings. Some of CSU’s environmental types see the new structure as a waste of precious resources. Others worry that the city’s stunning views of the foothills will be obstructed.

Ridpath understands the objections, but they play second string, in his opinion, to what a serious investment in big-time college athletics could mean for his alma mater. “I went to school here, I love Fort Collins, I’m a loyal fan of CSU football,” Ridpath says. “But this is an issue that will change the culture of CSU forever.” It’s about more than bricks and mortar. He argues that entering the semishady “business” of high-revenue college sports will be detrimental to a university that should be perfectly happy staying the way it is: above the sports fray, out of the TV spotlight, and focused primarily on students as academicians. “We are not and will not ever be Ohio State University,” Ridpath says, referring to the school that Jack Graham has cited as a model for CSU. “We should not strive to be OSU. We have to be satisfied with being Colorado State.”

The Hughes issue is the latest chapter in the ongoing—and heated—national debate about the role of athletics on American college campuses. Abysmal graduation rates; athletes being paid by boosters or agents; rampant NCAA violations for improper tutoring practices; illicit contact with high school recruits; workouts that don’t follow the rules—these scandals have become part of the daily college sports discourse. It’s gotten so bad that this past May, New York University hosted a debate on the subject with author Malcolm Gladwell, sportswriter Jason Whitlock, former NFL defensive end Tim Green, and Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist H.G. “Buzz” Bissinger of Friday Night Lights fame, who argued that football is “antithetical to the academic experience” and should be flat-out banned from college campuses.

Although Ridpath wouldn’t go quite that far, he disagrees with Frank and Graham that CSU needs to be a Top 25 mainstay. He’s more proud of CSU’s other rankings—those that say the school maintains above-average student-athlete graduation rates and is one of only 17 Division I football programs that has never had a major NCAA violation. Ridpath openly, and often snarkily, disagrees with the potential benefits Graham is promoting: that a new stadium will increase attendance and engender team spirit and tradition; that new facilities will attract better personnel and potentially help CSU shop itself to more esteemed conferences; that an on-campus stadium would benefit Fort Collins businesses; and that all these things could ultimately increase private donations to the university, a serious boon in times characterized by dwindling funding for higher education. “There simply isn’t any research that I’ve found that backs up the ROI Graham is touting,” Ridpath says.

The arguments of both sides are difficult to prove. What has worked at one school has bombed at the next. Although investing in a new on-campus stadium hasn’t increased attendance or fervor at Rutgers, it did exactly that at the University of Central Florida. As Texas Christian University’s strategically planned improvement in its football program has played out, its student applications have increased. The same, however, cannot be said of Marshall University, which went all in to achieve football prominence in the 1990s but didn’t enjoy more than a temporary bump in applications and enrollment.

Perhaps the best analogy to CSU’s situation is that of Boise State University. Be Bold CSU, the alumni-heavy group that supports a new stadium, has been touting the Idaho school’s accomplishments. “Five years of good football made all the difference for that university,” Be Bold’s Joel Cantalamessa says. Investing in a brilliant head coach and supporting its football program have done wonders for Boise State’s national image. BSU president Dr. Bob Kustra has said this success explains, anecdotally at least, why many new faculty members have come to Boise State, and is a causal factor in the university’s ascent from a Division I-AA school to Division I-A in the Western Athletic Conference to a BCS bowl winner and national title contender that recently joined the BCS-qualifying Big East Conference. (Historically, six conferences automatically qualify their champions for a BCS bowl game, which can score a school a multimillion-dollar payday. A four-team playoff will alter this structure in 2014.) BSU’s Big East move could bring an estimated $4 million to $6 million each year in TV money to the college, along with additional national exposure.

Ridpath says successes like Boise State’s are exceptions for the most part, and playing big-time football is a game most universities can’t win. He publicly asks Dr. Tony Frank to make the right decision for CSU—a decision Frank has said he’ll deliver this fall after reviewing the stadium advisory committee’s findings. On this night, the crowd at Lory clearly agrees with Ridpath. They are so hearty in their support that SOSHughes’ Bob Vangermeersch closes the meeting by reminding the audience of the group’s possible campaign to place an initiative on November’s ballot. In a move that would never fly in Tuscaloosa—or Baton Rouge or Athens, Georgia, or even in Boise—SOSHughes’ proposal would prohibit the city of Fort Collins from spending money on any infrastructure a new stadium might require.

There are three big windows in Jim McElwain’s corner office. From his desk chair, he can take in a panoramic view of the majestic peaks to the west. It’s a sight the Montana-born coach has longed for since leaving home to be the wideouts coach at the University of Louisville in 2000. After his stint in Kentucky, McElwain coached in East Lansing at Michigan State University, in Oakland with the Raiders, and at Fresno State before the big boys in the South came calling.

For many college coaches, the offensive coordinator job at the University of Alabama—maybe the most storied program in college football—would’ve been the offer of a career, a chance to don the houndstooth and continue a legacy of greatness that flourished under Paul “Bear” Bryant. Yet, when Alabama head coach Nick Saban called him with that job offer in 2008, McElwain turned him down—at first. He’d been offensive coordinator at Fresno State for less than a year, and “I figured I liked where I was and there was no reason to leave,” McElwain says. But when he told his boss, former Fresno State head coach Pat Hill, about the offer, “He told me I was crazy to turn that job down. So I called Nick back.”

McElwain spent four years learning from Saban, whose three national titles have earned him genius-level status among college coaches. But every coach wants to be his own man; no one wants to stay an assistant forever. McElwain began entertaining offers for head coaching positions. He even interviewed for the spot at CU, which the school filled with alumnus Jon Embree on a five-year, $725,000-a-year contract.

“Jim and I talked many times about the type of program he wanted to lead,” says Tim Bradbury, McElwain’s friend since college. “When the CSU job opened up I looked at my wife and said, ‘That’s the exact type of job that Jim has talked about for years.’?” Bradbury says that beyond a desire to return to the West, McElwain wanted to live in a college town, where his wife and three kids could feel at home. He wanted to work at a program where he could build a legacy. He didn’t need the school to be in a major conference; he didn’t need the team to have an illustrious history. What he did need was a boss whom he trusted and who was committed to building a strong football program.

When asked “Why CSU?” McElwain answers the question with a question: “Why not CSU?” He’s not worried that others don’t appreciate CSU as he does. He sees opportunity. Potential. He thinks CSU should be viewed as a destination job—“I mean, look at this town, look at those mountains!” he says—a place where success can be earned. In Fort Collins, McElwain sees a mini-Tuscaloosa; a place that, if McElwain and Frank and Graham have their way, may soon have plenty to cheer about on crisp, fall Saturdays.

Others have a different—and perhaps more practical—view on why McElwain chose CSU. Coach John L. Smith, the current head coach at the University of Arkansas, has known McElwain since Smith coached at the University of Montana, where he worked with McElwain’s mother. The two also coached together at Louisville and Michigan State University in the early- to mid-2000s. The two men still talk every few weeks—about family and friends and football. Smith says he sees the advantages of coaching in Fort Collins. With support from the university, a good coach, and some luck, Smith says Ram football can eventually contend for its conference title every year. He says what Frank and Graham are offering is an opportunity any coach would want: They’re creating fertile soil, and giving McElwain a shovel and seeds. It’s a situation you don’t find at every university. “If you’re Vanderbilt and you play in the SEC, it wouldn’t matter how much money or coaching or time you put in—you’re still going to get beat by Alabama every year,” Smith says. “CSU is not saddled with anything it can’t overcome. That’s a huge incentive.”

In ones and twos, the kids begin to trickle out of the locker room and onto the practice fields. McElwain, clad in shorts and a green Rams football pullover, waits for them at the entrance. He’s watching them intently and tries to elicit some reaction as they make their way toward his position. “Hey there, now, let’s go! Let’s go! Let’s hustle,” he barks. “Put that hat on, son. We’re gonna have a good day, a real good day. You’re gonna work for me today, right?!” He pops shoulder pads and smiles as his players trot by and give him a well-rehearsed “Yessir.”

McElwain’s OK with the canned response. In the confines of conference rooms and in the company of assistant coaches, he might be critical of these football players. But out here on the field, these players are his other children. So he encourages them, practices patience with them, wants nothing but good things for them. Of course, that doesn’t mean he’s against a little tough-love coaching when necessary.

As if on cue, the thud of bodies colliding reverberates across the practice field. Shouts ring out. The football has hit the turf. A mad scuffle to recover the fumble generates moans and groans as legs and arms tangle at the 45-yard line. McElwain strides up to the scrum, points to the fumbler, and yells loud enough for the girls on the adjacent softball field to hear: “Get me a new running back!”

McElwain doesn’t like mental errors or accept incompetence—from anyone. He says it’s just how he was raised, that he probably gets it from his dad, a man who had high standards for his five children. His former players agree, saying McElwain demands excellence, if not perfection. “But here’s the thing,” says Greg McElroy, a former Alabama quarterback who now plays for the New York Jets. “Mac’s not unrealistic in what he expects from his players.”

The coach expects, for example, that his players know that assaulting other people is not tolerated. Which is why he immediately and indefinitely suspended three CSU starters in April after they allegedly jumped out of an SUV and attacked four students after a verbal confrontation. The team rule they broke? “The rule is ‘Do what’s right,’?” McElwain says. “And it applies to everything.” The players have since been expelled.

Although today is just the fourth spring practice of the 15 the NCAA allows, McElwain’s influence on the Rams is already apparent. Unlike in years past, practice sessions are intense, fast, and efficient. There is no music blaring, and every member of the depth chart gets on the field, not just the first and second strings. McElwain doesn’t stand on the sidelines—he prowls behind the line of scrimmage, watching, slapping helmets, and seizing teachable moments.

The former college quarterback—McElwain played at Eastern Washington University—knows how important it is for the team to buy in to what he’s preaching, which is a you-reap-what-you-sow mantra. He understands these kids haven’t experienced success and that they’re still wary of him, his new approach, and what’s being sold—by the local media, by CSU’s marketing machine, by sports pundits—as a bold new era for CSU football. He’s aware his players are not deaf to the chatter about coaches’ salaries, a fancy new stadium, conference realignment, and what each of those things means for CSU. He knows they feel the weight of the university on their pads. But he wants them to follow his lead and push those distractions aside. After all, he says, it’s not his job—or theirs—to worry about anything except football.

Still winded from drills, the team gathers around McElwain as the sun sets over the foothills. The coach is smiling. He’s pleased with the effort and tells them today’s practice was the best one yet. “We have to put in the work now,” he says, “to get that success we want later.” When he asks, “You know what I’m gettin’ at?” the young men nod.

As the kids jog toward the showers, McElwain takes a circuitous route to the main gate. He kicks at a ball on the ground. He chats with an assistant coach and a referee. He jokingly tells a few reporters that the only thing he knows the team is good at right now is stretching, and he laughs to himself as he walks away. For a moment, the coach is alone with his thoughts, and he looks content. Maybe it’s because of the upbeat practice. Or maybe it’s because he believes he’s found the job—the one where he can, with time and effort, build a football legacy and where it now appears the higher-ups have a similar philosophy. McElwain must sense me watching him from across the field because he looks up, breaks into a grin, and hollers, “Hey Linz, whaddya think of that? We looked a bit like a football team, didn’t we?”