The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Prediction 1

The market will slow—just a little—this year.

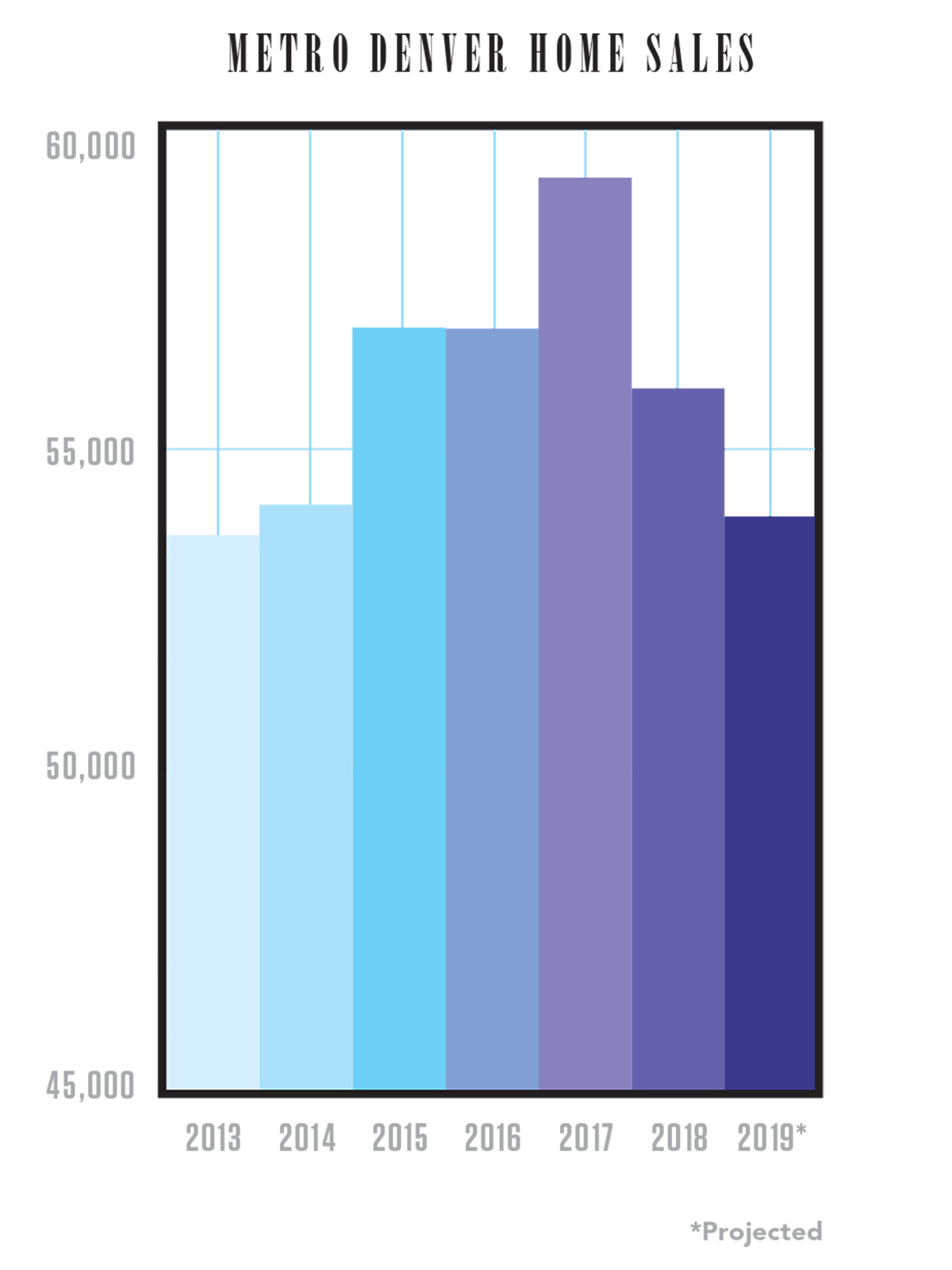

Buyers, take a breath. A small one. And make it quick, because you still can’t afford to take your sweet time deliberating over whether to stretch your budget to get that extra bathroom—even as the market will likely affect a slightly more leisurely vibe in 2019. Littleton-based Development Research Partners is forecasting a six-year low for existing home sales closed over the entire year (see graph). Multiple bids will continue to be the norm; however, come July and August, Heather Heuer, senior vice president of sales operations for Liv Sotheby’s, expects higher inventory to allow buyers a little more time for deliberation. That could be enough to temporarily slow the feeding frenzy around new listings. Recent buyers and would-be sellers can still enjoy nice, deep, self-assured inhales, though, because our economy is now diversified enough (thanks tech, health care, and marijuana booms) to maintain its robustness. Says Heuer: “The bottom dropping out isn’t going to happen.”

Prediction 2

Interest rates will remain stable in the near term.

The average interest rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage at press time (early April): ~4%. That’s almost a half percent down from where rates were in early 2019, which may sound like good news for home shoppers—but the tantalizing rates could encourage more buyers to jump into the market, increasing competition. Regardless, experts expect rates to stay in the low fours this year.

(What are the best neighborhoods in Denver? Check out our 2019 list!)

Prediction 3

Millennials and baby boomers will flood the market, in some cases competing for the same properties.

At about a quarter of our population, millennials are the largest generation in the Centennial State, on track to account for 45 percent of mortgages in 2019, according to realtor.com. Plus, the largest cohort of millennials is approaching 30, an age at which that demographic, broadly speaking, is transitioning to a more stable lifestyle—and, perhaps, finally able to scrape together a down payment. “They don’t necessarily need the square footage,” says Libby Levinson, a broker associate at Kentwood Real Estate. “They want the lifestyle; they want to be living their best lives on Instagram and have access to things that let them do that.”

Then there’s the baby boomers—many in or nearing retirement—who make up 22 percent of Colorado’s population. They’re often still active and healthy but, if they can afford it, are looking to trade five-bedroom homes outside the city for smaller floor plans in walkable neighborhoods. “Boomers don’t want to have to maintain empty space,” says Liv Sotheby’s Heather Heuer.

What all that means is a two-bedroom bungalow in Highland or a condo in Cherry Creek may pull in offers from both demographics. Who will win out? Who knows? But this (highly generalized) breakdown of where their dream homes intersect and diverge could help buyers in both categories target properties that are less attractive to the other generation—aka the competition.

Prediction 4

The slot home slap-down will continue to change how developers look at infilling burgeoning areas.

It’s difficult to create a neighborly, wave-from-the-front-porch feel in a community when homes don’t have front porches—or even true front doors. That was the concern of residents in neighborhoods like Jefferson Park and Highland, where “slot home” designs (those boxy multifamily housing units perpendicular to the street, sometimes facing each other with a space between) have recently proliferated. Denver’s City Council responded to the vocal opposition by unanimously passing an amendment a year ago that essentially banned the design in certain zoning districts, to great fanfare from local city planners and architecture buffs. The news wasn’t as happily received by developers, though: Lots that could’ve held more dwellings via slot home designs will see a 30 percent reduction in unit density, according to Ben Gearhart, co-owner of Modus Real Estate, which develops and sells property primarily in northwest Denver. To manage costs and keep prices attainable for buyers who find modern rowhome-style living in dense, walkable areas attractive—including millennials who are priced out of the stand-alone bungalows and Denver Squares in popular urban areas—some developers are becoming more creative with designs and floor plans. Others have redirected operations to areas where they can still build slot homes. Says Gearhart: “There was a lag time [in new units] while we worked out the kinks.”

Prediction 5

Prospective new-build buyers will need to look closely for quality issues.

There’s something exciting about a never-been-lived-in home: the shiny appliances, the unmarked walls, the scuff-free floors. This is especially true considering the painful asking prices for some of central Denver’s older homes, many of which straddle the line between “historic charm” and “gut it to the studs.” But don’t let the clean lines and airy floor plans of those three-story, new-build townhomes in Jefferson Park or Five Points lure you in without doing your due diligence on the craftsmanship.

“I’m not saying don’t buy new construction,” says Kentwood Real Estate’s Libby Levinson. “I’m just saying keep your eyes peeled. Many builders offer a one-year bumper-to-bumper warranty, but I suggest addressing as many issues prior to closing as possible.” In particular, pay attention to the following seemingly minor details—some of which can be surface-level red flags for deeper shortcomings in the construction process—before signing on the dotted line:

- Check the trim on doors and baseboards. Nail holes or open seams may mean the builders skipped solid wood in favor of another product or rushed the finishing stage.

- Look for cracked and uneven grout lines or split caulking in tiled areas, like between the kitchen counter and the backsplash. These issues could signal movement in the house.

- If you see dings or marks on the cabinets or notice a door that catches when it opens, ask that it be fixed before move-in. It can be a hassle to repair a single cabinet after you close.

Prediction 6

Savvy buyers will take chances on Denver’s next-big-thing neighborhoods—and cash in, if they choose correctly.

Forget Wash Park and Highland. And honestly, Sloan’s Lake, Baker, and Berkeley aren’t really up-and-coming anymore either. (Pssst: They’ve already arrived.) That doesn’t mean, however, that the next “it” Denver ’hood isn’t out there. We polled nearly a dozen real estate experts to find out where they’d consider taking calculated risks—and why.

Neighborhood: West Colfax

Current vibe: Centered on its namesake artery, West Colfax is bustling but dated in a rundown-motel kind of way, with pockets of artistic revitalization.

Transformative factors:

- Community investment in projects like a redesign of the dangerous interchange at West Colfax Avenue and Federal Boulevard

- Spillover development from the amenity boom in adjacent Sloan’s Lake (Alamo Drafthouse Cinema and Tap & Burger Sloan’s Lake, for example)

Look for: Recently constructed townhomes starting in the $400,000s

Caveat: Thanks to an amendment that restricted slot home designs (see Prediction 4), inventory may dip while developers literally go back to their drawing boards.

Neighborhood: Sun Valley

Current vibe: Industrial lots coexist with mainly public housing, and the area is isolated from most city amenities by waterways and poorly planned thoroughfares.

Transformative factors:

- A $376 million public housing redevelopment plan that will raze 333 subsidized housing units and replace them with 750 new mixed-income units, including moderate-income and market-rate homes, by the end of 2024

- A master plan to overhaul the parking lots surrounding Broncos Stadium at Mile High into a walkable urban entertainment district

- The ambitious, estimated 20-year RiverMile project that would create a bustling waterfront enclave along the South Platte River

Look for: New-build multifamily residences (prices are TBD as Sun Valley is an untested market for new construction)

Caveat: Construction chaos will play out in this historically low-income neighborhood for years, as will passionate debates about the ramifications of resident displacement.

Neighborhood: Elyria-Swansea

Current vibe: Factories, rail yards, and the interstate serve as less than desirable backdrops for single-family homes.

Transformative factors:

- The $1 billion National Western Stock Show Complex overhaul, projected to draw more than two million visitors annually after construction is completed in 2024

- The $1.2 billion Central 70 Project (reconstruction and expansion of I-70 between Brighton Boulevard and Chambers Road over the next three to four years, including a four-acre park that will be built over the newly lowered stretch of interstate)

Look for: Condos and townhomes in the $400,000 to $450,000 range, with improved roads and a cleaned-up South Platte River zone

Caveat: On top of gentrification concerns, the widespread construction isn’t helping chronic pollution issues in the area.

Neighborhood: Athmar Park

Current vibe: Older homes that have retained their character but may need face-lifts populate this undiscovered, modest area, the gem of which is Huston Lake Park.

Transformative factors:

- Developers pulling permits for projects on West Alameda Avenue, west of South Santa Fe Drive

- Two recent grants from Kaiser Permanente that helped the area’s already strong neighborhood association form an Active Living Coalition to address transportation and mobility issues in the neighborhood, including bike and pedestrian access, streetscaping, and traffic safety

Look for: English Tudors and ranches that, in the high $300,000s to mid-$400,000s, are still within reach of some first-time buyers

Caveat: These are likely dated homes that need work. The money you spend on remodeling should ultimately be a win—but you have to invest without proof the area will turn around.

Prediction 7

Buyers will work the calendar to their advantage in 2019.

Fueled by low inventory levels between 2013 and 2018, the Mile High City became one of the nation’s hottest seller’s markets. That won’t change dramatically this year. But it might be “a less good seller’s market, for lack of a better way to put it,” says Megan Aller, an account executive at First American Title Insurance Company. Buyers should capitalize on more favorable timing by using our adaptation of Aller’s 2019 strategy sheet of projections for detached single-family homes—essentially a horoscope for real estate in the Denver metro area.

Active Listings

Buyers beware: When fewer homes are for sale, competition increases, which drives prices up.

Homes Sold

More successful closings (these homes likely went under contract 30 days prior) is a sign of higher buyer activity, thus more competition, which is an advantage for sellers.

Percent of Asking Price Received by Seller

Numbers over 100 percent in this row mean multiple offers are likely, due to fewer listings and more buyer activity. In April, May, and June, homes have closed, on average, above asking price for the past seven years—i.e., be prepared for bidding wars.

Change in Average Sale Price from Previous Month

Rising demand and short supply nudge prices up in late winter and early spring, but come midsummer, house-hunting fatigue sets in. Inventory goes up, giving buyers more negotiating power and (gasp!) perhaps even forcing price cuts.

Average Days on Market

Homes listed in March, April, and May (with probable closings, then, around April, May, and June) are likely to sell faster than those at any other time of year—meaning the market was good for sellers who got their homes ready in time for the beginning of real estate season.

Months of Inventory

A six-month supply of housing is where the stars align for a balanced market, in which neither party has a distinct advantage. Metro Denver’s consistently low inventory still favors the seller, but looking ahead in 2019, August, September, and October look to be the most auspicious months for buyers.

Prediction 8

Granny flats—also called mother-in-law suites or accessory apartments—will become more popular, as long as local municipalities ease up on regulations.

Less than four months ago, Denver City Council approved zoning changes in Elyria-Swansea that gave a few residents the go-ahead to build accessory dwelling units (ADUs) on the same properties as larger homes. The special dispensation was OK’d in an attempt to restore housing density to an area blighted by the I-70 expansion. But for many, the idea has merit as more than just a concession for razed homes. A studio over the garage, for example, could allow more members of a family to live on the same plot of land, potentially defraying mortgage costs. Or a small cottage or carriage house in the backyard could generate rental income.

Despite what seem to be the many upsides of ADUs, they are verboten in much of the city, partially because residents fear they could encourage overcrowding. Only after the zoning code was replaced in 2010 were they allowed in certain neighborhoods that advocated for them, like Curtis Park; since then, more than 200 ADUs have been built citywide. However, that all may change with the next iteration of Blueprint Denver, the city’s 20-year land use and transportation plan. (At press time, it was headed to a City Council public hearing and vote on April 22.) The new plan recommends allowing ADUs in all residential neighborhoods and eases previously restrictive construction regulations. “There is a huge demand,” says Kassidy Benson, managing broker and owner of Living Room Real Estate in Denver. “A lot of people I’m talking with are getting ready to have kids, and they want this type of housing literally for a mother-in-law, or for a nanny; or they have kids graduating from college who don’t want to live with them but need to.”

Even if the red tape is cleared away, ADUs face another hurdle: expense. According to Benson, the projects rarely cost less than $200,000—a prohibitive upfront figure for many families who might be dreaming of adding a rental unit for extra cash. Still, she likes to imagine the potential positive impacts to the city’s neighborhoods: “As ADUs start to come in, alleys will become more like streets,” Benson says. “They’ll become activated, versus the way it is now, with trash cans and cars coming in and out of garages.” Inspired by her utopian vision? Living Room’s website maintains a searchable database of current ADU-zoned properties for sale in Denver—and that could mean good news for Granny.

Prediction 9

First-time home shoppers will learn to love Denver’s increasingly urban suburbs.

On a recent sunny Saturday afternoon, my husband and I walked a little more than a mile from our 2,300-square-foot, recently renovated four-bedroom house—which we purchased in July 2017 for $405,000—to Denver Beer Co. The brewery was buzzing but not overcrowded; we easily found seats on the patio at which to sip our Incredible Pedal IPAs in the light of the fading sun and, later, under the glow of the twinkly cafe strands strung above us. To anyone who’s shopped for houses within strolling distance of Denver Beer Co.’s LoHi taproom, this probably sounds like a dream sequence. But as thirtysomething first-time homebuyers, it’s our reality—in Arvada, that is, where the popular beer-maker has a second location.

The decision to leave the Mile High City wasn’t easy. Three years in a 500-square-foot Baker rowhouse, however, had us craving more space—for our 60-pound husky, for dinner party guests, and for the family we hoped to grow. When we started comparing costs (today, prices in the downtown Arvada area average $381,000, versus $585,000 in Highland), our attachment to a Denver zip code quickly waned. Plus, Arvada feels decidedly urban in many ways. The northwest suburb’s Olde Town area boasts three breweries; a winery; more than a dozen nonchain restaurants and cafes; shops that range from a fly-fishing store to a hipster haven called Vouna complete with beard oils, air plants, and a live-in rabbit named Emma; a seasonal Sunday morning farmers’ market; and a stop on the G Line (set to open on April 26, as of press time) to Union Station.

Of course, Arvada isn’t the only neighboring city urbanizing business districts to entice residents. Englewood, for example, hired its first chief redevelopment officer in 2018 to shepherd the rebirth of key areas like the South Broadway corridor and CityCenter, a 55-acre, transit-oriented development site at South Santa Fe Drive and Hampden Avenue. With Denver claiming the title of the 13th most expensive housing market among metropolitan areas in the country and wages generally failing to keep pace, more would-be homeowners will inevitably expand their search parameters to include the ’burbs. My message to them? Come on in. The water—and the beer—is better than fine.

—Jessica LaRusso

Prediction 10

Artificial intelligence will replace both the MLS and human real estate agents.

We kid, we kid…kind of. REX, a Los Angeles–based real estate tech startup that expanded to Denver in 2018, has already taken the first step by offering clients a flat two percent fee (versus the typical five or six percent) to list their properties. Then, REX’s software pushes the listing out to likely homebuyers via digital channels like Zillow and Facebook. “REX looks at consumer search patterns, purchasing habits, life-event patterns like having a child, and census data and triangulates that info with the house that’s for sale,” says Jonathan Friedland, REX’s head of policy and communications. Until the machines fully take over, what are the benefits and drawbacks of using REX?

Pros

- Since REX doesn’t list on MLS, sellers don’t pay a buyer’s agent commission. So on, say, a $750,000 home, the model could save you $30K.

- Instead of waiting for the perfect buyer, REX proactively markets your listing to people its algorithms have identified as strong candidates.

- REX claims it streamlines what can be a complex transactional process, eliminating paperwork and lengthy contracts.

Cons

- Serious buyers are still attached to the MLS, where most homes are listed.

- Because the model is built on the assumption that the buyer is not using an agent either, shoppers who insist on working with their own agents but end up purchasing homes listed on REX may need to cover their agents’ fees.

- Algorithms and bots still can’t grasp those critical yet intangible factors, like emotional attachment to certain areas or the nuances of taste.

Prediction 11

Developers will continue to favor apartment construction over building condominiums.

The cranes dotting Denver’s skyline make it clear that multi-unit, mixed-use construction is afoot. But will those eventual dwellings be for lease or purchase? Metro-area renters may well be hoping for more entry-level condos where they could maintain their urban lifestyles and build equity for the same or even less monthly output. We asked Steve Ferris—a city planner who founded the Denver-based Real Estate Garage to help developers and landowners usher such complex projects through approval, zoning, and government negotiation processes—to explain why condo proliferation isn’t likely to happen.

5280: Labor and land shortages are issues for both types of buildings—so what’s driving the continued apartment boom?

Steve Ferris: People are dissatisfied with their real estate options, and they’re more transient with their lifestyles. Plus, an apartment isn’t a bad return for a private equity firm; it’s one of the safest investments anyone can make, so the capital is there.

Aren’t there more hoops to jump through when you’re building condos, too?

Yes. Apartments are easier to get done. Apartment developers can put land under contract in 120 days. Condo developers have to ask the owner to hold the land while they work on getting enough presales to get financing.

Does that mean there’s an oversupply of apartments?

There will be an oversupply, but supply and demand will even out in two to three years, assuming economic conditions stay positive and jobs keep showing up.

Could current apartment buildings ever be converted to condos?

Possibly, but apartments are built differently. For example, most aren’t individually metered for heating and cooling, and the sound-protection barriers between units typically aren’t built [to the standard of] condos.