The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

Red rock formations. Plunging canyons. Tumultuous rivers. Skyscraping peaks. The Mountain West has a geographical profile that suggests Mother Nature took a little extra time here—which is why experiencing some of her best handiwork is a must. From a long list of contenders, we selected 10 classic landmarks you should make plans to see as soon as possible.

Longs Peak | Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

The northernmost fourteener in the Rocky Mountains, 14,259-foot Longs Peak (pictured above) rises resolute from inside Rocky Mountain National Park and stands watch over Colorado’s Front Range. Mountaineers the world over come to the Centennial State for the singular purpose of climbing the famed Keyhole Route, so named for the oddly shaped notch that lies at the top of a sprawling boulder field. Would-be summiters—who must navigate narrow ledges, falling rocks, and a 15-mile round-trip climb that requires some advanced mountaineering skills—will pass through the Keyhole and scramble the final 1.5 miles to the top.

Did You Know?

The Agnes Vaille Shelter—visible just down and to the left of the Keyhole—is a beehive-shaped stone hut originally built in 1927. It’s named for the first woman to summit Longs Peak via its east face in the winter. After successfully summiting the mountain in 1925, Vaille slipped on the descent, fell approximately 100 to 150 feet, and died of hypothermia while waiting to be rescued.

If You Go:

You can climb Longs Peak any day that Rocky Mountain National Park is open; however, winter ascents are highly technical, meaning ice axes and crampons are necessary. The most snow- and ice-free time to climb the fourteener is typically from mid-July to mid-September, but checking the forecast before you go is imperative. You’ll want to begin your ascent by 3 a.m. so your party can be off the mountain—10 to 15 hours later—before afternoon thunderstorms appear. A one-day pass to the park is $20 per vehicle; a seven-day pass runs $30 per vehicle.

Oxbow Bend | Grand Teton National Park, WY

When the Snake River’s surface relaxes into a glassy plane at Oxbow Bend, the reflection of 12,605-foot Mt. Moran is breathtaking, making the setting one of the most photographed in Grand Teton National Park. But even when a whisper of wind erases the mirror image, there are still plenty of reasons to hike—or, better yet, stand-up paddleboard—in the area. Sandhill cranes, elk, moose, grizzly bears, trumpeter swans, otters, Canada geese, blue herons, bald eagles, ospreys, and American white pelicans all call the slow-moving, shallow waters and cottonwood-lined banks home.

Did You Know?

Leave it to the French to bestow lurid names upon our lovely geography. The story goes that Grand Teton National Park got its name from 19th-century French fur trappers, who described the range as “les trois tetons”—or “the three breasts.” The hunters were likely referring to Grand Teton, Teewinot Mountain, and Mt. Owen.

If You Go

One of the vehicle pullouts at Oxbow Bend is on U.S. Highway 191 between Moran Junction and Jackson Lake Junction. To paddleboard or kayak the Oxbow Bend, rent equipment in Jackson, pick up a $10 Grand Teton National Park boating sticker (available at any visitor center), and put in at Cattleman’s Bridge or Jackson Lake Dam. A one-day pass to the park is $25 per vehicle; a seven-day pass runs $35 per vehicle.

Havasu Falls | The Grand Canyon, AZ

The water here bears an uncanny resemblance to Cool Blue Gatorade, which wouldn’t be odd if Havasu Falls were spilling into warm Caribbean waters. Instead, Havasu Creek’s 98-foot-tall cascade tucks inside the Grand Canyon, creating an oasis among the red rock. A rare cocktail of magnesium, calcium, and calcium carbonate suspended in the spring reflects the sun, giving it the color of a fluorescent blue highlighter. The vivid water has long drawn people to its banks. In fact, the Native American tribe that owns the land calls itself the Havasupai, meaning people of the blue-green water.

Did You Know?

Unlike many ecologically sensitive places you’ve probably visited (e.g., Glenwood Canyon’s Hanging Lake), swimming in Havasu Creek and at Havasu Falls is allowed. Which is a relief because the 70-degree water feels exceptionally refreshing after a 10-mile hike in temps hovering around 100 degrees in the summer.

If You Go

Planning a trip to the falls is challenging. The Havasupai Tribe controls access to the area, requiring a permit and at least a one-night stay in the canyon. Permits are limited and difficult to procure; try to reserve a permit before the end of February for a summertime visit. Reaching the falls requires a 10-mile hike in the hot desert sun. The first-come, first-served no-facilities campground where your group (20-person limit) must stay at least one night (there’s a three-night max) is about a five-minute walk from the falls.

Delicate Arch | Arches National Park, UT

Although it’s located within one of the world’s most dramatic landscapes—Utah’s Arches National Park—60-foot-tall Delicate Arch seems to know just how captivating it is. A free-standing doorway of reddish sandstone, Delicate’s preternatural beauty has been wooing onlookers—Native Americans, 19th-century homesteaders—from its high perch since time immemorial. But those who have yet to see her should remember: Gravity and erosion make the park’s 2,000-some fins, spires, and arches impermanent. Wall Arch—which stood 71 feet wide and 33 feet high—collapsed in 2008.

Did You Know?

The 15-by-17-foot cottonwood log cabin that sits near the trailhead to Delicate Arch was built in 1906 by John Wesley Wolfe, a Civil War veteran who homesteaded a 100-plus-acre parcel of land north of what was then the tiny hamlet of Moab. Wolfe’s daughter, Flora, took one of the earliest known photographs of Delicate Arch.

If You Go

There are three ways to experience the grandeur of Delicate Arch. The first is the Lower Delicate Arch Viewpoint, where you can walk about 100 yards from a parking lot to see the rock sculpture from a mile away. The Upper Delicate Arch Viewpoint requires a half-mile trek but provides a more unobstructed view. Or hike three miles (round trip) from the trailhead at Wolfe Ranch to stand inside the arch’s 46-by-32-foot opening. The park entrance fee is $25 per vehicle and covers seven calendar days.

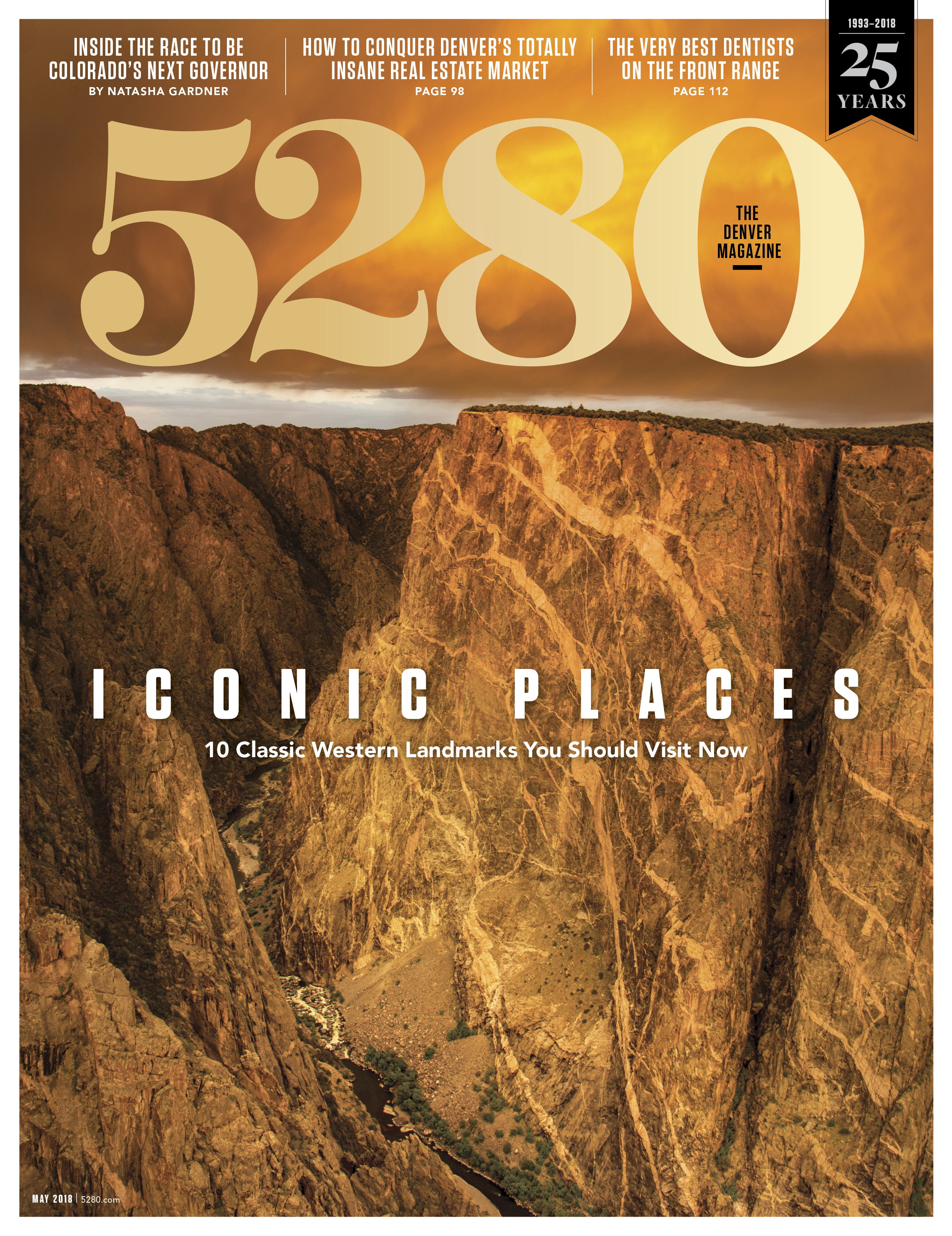

Painted Wall | Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, CO

Nearly every inch of the 48-mile-long Black Canyon of the Gunnison provides the rarefied views one expects in Colorado. But the 14 miles of the gorge protected by Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park defy expectations. Staggeringly deep and nigh impenetrable (for everyday recreationists and acrophobes), the chasm owes its existence to the churning Gunnison River, sometimes visible far below. But visitors don’t have to strain to see the Painted Wall; at 2,250 feet, the tallest vertical cliff in Colorado commands observation. The immense Precambrian gneiss and schist rock wall exhibits generous brushstrokes of granitelike, pink-hued pegmatite.

Did You Know?

There are approximately 145 known rock climbing routes in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, several of which snake up the Painted Wall. Be forewarned that these multipitch traditional climbs are known for their loose rock and once-you-begin-you-can’t-go-back routes. Translation: Beginners need not apply.

If You Go

Check out the dizzying heights of the Painted Wall from a viewing area along South Rim Road. The Painted Wall viewpoint is sometimes inaccessible during the winter; call the park in advance to find out if the road has been plowed. The park entrance fee is $20 per vehicle and covers seven calendar days.

Crystal Mill | Crystal, CO

True, Mother Nature did not construct Colorado’s famed Crystal Mill. Yet the precariously balanced wooden structure sits so perfectly atop a rocky outcropping along the frothy Crystal River that it looks, well, natural. Rivaling even the Maroon Bells for Instagram worthiness, the scene is especially spectacular when the aspens turn gold in the fall. Built in 1892 by prospectors from what was then the booming mining town of Crystal (about an hour southeast of Carbondale), the mill harnessed the force of the river to power an air compressor. The compressor then fueled machinery and tools at nearby silver mines.

Did You Know?

The area surrounding the mill—from Carbondale to Marble to Paonia, on the other side of McClure Pass—has long been a cache for those looking to extract resources from the earth. Silver, coal, and white marble have all been harvested from what is arguably some of the prettiest terrain in Colorado.

If You Go

Located about 33 miles from Carbondale, the mill sits adjacent to the river between Marble and what is now the ghost town of Crystal. Passable only during the summer and fall, County Road 3 requires a high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle or trustworthy horse. Hardy hikers or mountain bikers could also traverse the 5.5 miles from Marble.

Hidden Lake Trail | Glacier National Park, MT

There are very few places in the continental United States where one can ooh and aah at the purple- and absinthe-hued aurora borealis. The northern reaches of Glacier National Park—where slow-moving ice carved craggy mountains, sweeping valleys, and jewel-tone lakes over thousands of years—offer that rare opportunity. There’s no way to predict exactly when the light show will go on; however, a late summer hike along Hidden Lake Trail (off Logan Pass) in the wee morning hours is as sure a bet as any.

Did You Know?

If you’ve never been to Canada, this is your chance. Citizens of Canada and the United States can show their passports at the Goat Haunt Ranger Station—which lies inside the park—and cross the border.

If You Go

From the town of St. Mary, on the east side of the park, take Going-to-the-Sun Road (portions may be closed due to weather from October through early July) to the Logan Pass Visitor Center. The trailhead for Hidden Lake leaves from the parking lot. The 2.6-mile (one way) relatively easy trek to the lake winds through alpine meadows, where there is hardly any shade (during the day) and little protection from the wind (all the time). The park entrance fee ranges from $20 to $30 per vehicle, depending on the season, and covers seven calendar days.

Antelope Canyon | Navajo Tribal Park, AZ

Scoured by flash floods and blasted by sand for millennia, the reddish sandstone canyons near Page, Arizona, have been sculpted by time into sunbeam-lit masterpieces. The most famous of these slot canyons is Antelope Canyon, with its trademark smooth rock, which appears to be flowing horizontally. Antelope is actually split into two sections—upper (pictured) and lower—both of which are worth a visit. If you’re seeking to photograph those signature rays of light, though, you’ll need to take a tour of the upper slot between late May and late August.

Did You Know?

Rare but devastating flash floods can rip through Antelope Canyon without warning, typically in the months of March, April, August, and September. In 1997, 11 tourists died during a guided tour of the lower slot, and although no one was killed, intense flash flooding was reported in the canyon in early August 2013.

If You Go

Antelope Canyon is located on Navajo Nation land, and the only way to see the slot canyons is with a commercial guide. According to the Navajo Tourism Department, there are five outfitters that tour Upper Antelope Canyon and two that take visitors to the lower section. Prices and times vary.

Tularosa Basin Dunefield | White Sands, NM

Coloradans are not unfamiliar with illogically placed sand dunes; after all, Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve’s 30-square-mile dunefield is one of the state’s most spectacularly weird settings. Yet White Sands National Monument in New Mexico ups the ante on bizarre in several ways. First, the giant dunefield in Tularosa Basin encompasses 275 square miles, an almost incomprehensibly large swath of land. Second, most sand on Earth is made of quartz; however, 99 percent of the mineral deposits at White Sands are pure gypsum sand—an oddity because gypsum is water soluble, like salt. Finally, the flourlike color of the dunes makes for an ethereal environment with a mood that shifts as light and shadow dance across the sand.

Did You Know?

White Sands National Monument is surrounded by White Sands Missile Range, an active U.S. Army installation. The base has a storied past: It was a key location for the Manhattan Project and the testing ground for the first atomic bomb. Today, it’s possible for monument visitors to come upon collateral debris and even wayward unexploded ordnance in the dunefield. As such, any foreign objects found in the sand should be left alone and reported to a monument ranger.

If You Go

White Sands National Monument is open every day except December 25. Springtime can be windy, but the yucca plants begin blooming in late April, making for gorgeous photos. Summer can be downright hot—and crowded. Fall is a great time to visit, not only for milder temps, but also because the cottonwoods turn gold. The entrance fee is $5 for adults; children 15 and younger are free.

Grand Prismatic Spring | Yellowstone National Park, WY

Everywhere you look in Yellowstone National Park, there’s evidence that this mesmerizing landscape tiptoes an invisible line between a steady simmer and boiling over. Geysers. Mud pots. Hot springs. The earth here seems angry—bubbling, spewing, and huffing with barely controlled geothermal energy. Don’t let anyone tell you that fury can’t also be beautiful, though. Exhibit A: Grand Prismatic Spring. The third-largest hot spring in the world, it’s more than 120 feet deep, 370 feet in diameter, and a searing 160 degrees. But it’s the colors—a deep blue center with rings of green, yellow, orange, and red—that capture everyone’s gaze. Fortunately, in 2017 the park opened the 0.6-mile Grand Prismatic Spring Overlook Trail to help visitors gain the bird’s-eye view necessary for taking in the spring’s full majesty.

Did You Know?

The multihued concentric circles that emanate out from the blue center of Grand Prismatic Spring are caused by varying species of heat-loving organisms. Each colored ring signifies a different temperature and the different thermophiles that can live there. To survive in the harsh environments, the organisms produce photosynthetic and chemosynthetic pigments, which in turn reflect specific wavelengths of visible light, making them appear in a rainbow of colors to the human eye.

If You Go

Yellowstone is open year-round, but services can be limited and roads, trails, and attractions can be closed or go unmaintained from September through June because of adverse weather. In the summer months, heavy crowds can overwhelm trails, parking areas, lodges, and campgrounds. The park entrance fee is $30 per vehicle and covers seven calendar days.

Leave No Trace

Special places like the ones we’ve highlighted here experience overuse and abuse from the tens of thousands, if not millions, of people who travel to see them each year. If even a small percentage of those folks disregard the tenets of leave no trace—leave what you find, stay on defined trails, dispose of trash and waste properly, etc.—these paragons of the Western landscape could be irrevocably damaged. In 2014, for example, a tourist tried to get an aerial view of Grand Prismatic Spring using an illegal drone—which crashed into the center of the pool. Learn how to be a caretaker of the land by visiting lnt.org.