The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals. Sign up today!

The Leadville hospital director had his finger in Ken Chlouber’s face, which wasn’t good for his finger. If you’ve seen Ken, with those cowpuncher boots on his size 13 stompers and that miner’s mug as craggy as the rock he blasted for a living, you’d figure out pretty quickly that you don’t put a hand near his face unless you’re dead drunk or dead serious.

Dr. Bob Woodward wasn’t drunk. “You cannot let people run a hundred miles at this altitude,” he railed. “You’re going to kill them.”

“Good!” Ken shot back. “At least that’ll make us famous.”

Ken had spent too many nights in the Leadville mines with dynamite in his jacket and a blasting cap in his helmet to take life lightly. “Boys,” he used to tell his crew on the graveyard shift, “we’re going under that big rock and blowing it up, and if one of us gets out alive, it’s going to be Ken. So if you want to walk out with me, you’ll do exactly what I say.” Ordinarily, he doesn’t joke about carnage, but these were not ordinary times. His neighbors were drinking hard, punching their wives, sinking into depression or fleeing town. A sort of mass psychosis was overwhelming the town, which is one of the early stages of civic death: First, people lose the means to stick it out; then come fights, arrests, and robberies; finally, folks lose the desire. It was 1982, and overnight Leadville had become the most jobless region in North America.

The Climax Molybdenum Mine had suddenly shut down, taking with it the paycheck of nearly every able-bodied man in town. Without Climax kicking in its enormous share of the property tax-in other words, without a local economy-schools and city budgets soon would be bankrupt. An epidemic of foreclosures was only a matter of time. A vision of the future was right across the mountains in Winfield and Vicksburg, and in dozens of other Colorado ghost towns that dried up after a boom. Leadville was ticking down to Deadville.

“Hell and half of Georgia couldn’t get me to leave,” Ken liked to say. He loved watching the sunrise over Mt. Massive as he left the mine tunnels at dawn, and honking at buddies on Harrison Street from his black pickup with its flame-painted hood. He loved bringing his burro right into the bar for a beer every year after the Boom Days races. Ken loved Leadville, so he came up with a plan to save it.

Unfortunately, it was a really bad one. Ken wanted to start a 100-mile footrace through the mountains-a horrendous physical challenge, which would attract…actually, as far as anyone knew, the only people who ran ultramarathons were the Boulder housecleaners who called themselves Divine Madness (which everyone said was a sex cult) and those Sri Chinmoyists from New York who shuffled around the block all night. As far as publicity, the spectacle of a few silent, skinny obsessives chasing each other through the woods in the dead of night had all the ingredients of terrible TV, except in the case of a horrific catastrophe, which, according to Leadville’s leading medical expert, was a near certainty. Ken wouldn’t turn Leadville into Vail; he’d turn it into Jonestown.

Unfortunately, it was a really bad one. Ken wanted to start a 100-mile footrace through the mountains-a horrendous physical challenge, which would attract…actually, as far as anyone knew, the only people who ran ultramarathons were the Boulder housecleaners who called themselves Divine Madness (which everyone said was a sex cult) and those Sri Chinmoyists from New York who shuffled around the block all night. As far as publicity, the spectacle of a few silent, skinny obsessives chasing each other through the woods in the dead of night had all the ingredients of terrible TV, except in the case of a horrific catastrophe, which, according to Leadville’s leading medical expert, was a near certainty. Ken wouldn’t turn Leadville into Vail; he’d turn it into Jonestown.

Ken organized the first race in 1983, and sure enough the freaks were first in line. Some were burro racers who usually ran tied to a donkey; some were mountaineers missing toes; some, as predicted, were housecleaning cultists from Boulder. Interesting folks, certainly, but not the glam crowd that builds a tourist trade. However, that was only the beginning. The race has grown in ways that not even Ken, in his wildest, weirdest hopes, could have imagined. Llamas appeared, and a billionaire, and mystic guru Indians, along with a mysterious wanderer called The White Horse. Strange things began happening in Leadville-strange and wonderful things.

On August 27, 1983, less than a year after Ken’s brainstorm-and at the exact hour the miners would usually be in the middle of a graveyard shift-dark shapes began moving through the Leadville streets. The ones who’d arrived the day before couldn’t believe how cold it was, or how much their heads were aching. They now understood why, at around Leadville’s 10,152-foot altitude, planes pressurize cabins. By 4 a.m., one woman and 44 men had gathered at Leadville’s only traffic light. How many would still be alive the next morning was still in doubt. Cindy Corbin, the Leadville hospital obstetrics manager who gave prerace physicals, was sure some contestants were going to die. “Why wouldn’t they?” she says. “They’d be alone all night in the mountains, with those snowstorms we get. And they were already so wired, their blood-pressure readings were off the charts.” After Dr. Woodward protested that the race bordered on criminal negligence, Ken asked hospital Chief of Staff Dr. John Perna to be race medic. Perna knew his hospital director, Woodward, had a point-severe altitude sickness and exposure were the most obvious killers-and Ken’s sales pitch only made it sound worse.

“It’ll be in August,” Ken had said.

OK, Perna thought, we can now add heat exhaustion to hypothermia.

“We’ll go over Hope Pass heading out and coming in,” Ken continued.

Plus possible dehydration, frostbite, fractures, and hypoxia-induced delirium and disorientation.

“And we’ll cut the last ones off at 30 hours.”

Which was way longer than the Geneva Convention allowed German prisoners of war to work at a stretch at nearby Camp Hale.

Perna delivered his assessment as gently as possible. “This could become one of those Everest expeditions where you, uh….” Perna struggled for a euphemism. “Where you lose a few.” Yet Perna agreed to do it. The doctor in him didn’t like the runners’ risks, but the Leadville in him disliked the kind of despair-induced injuries he’d begun seeing in his ER. Whatever psychological chemistry allows miners to live in a remote, mountaintop town and risk their lives underground every day also made them, once the work was gone, unusually prone to self-destructive behavior.

“Domestic violence and alcoholism was an increasing problem,” Perna says. “And ultimately, I think we faced the disappearance of the city.” Leadville only had about 4,000 residents-about as many people as you’d find in the stands at a minor-league baseball game. Like Ken, Perna sensed the “lethal doldrums” developing in Leadville. The miners needed to get out of the bars and do something. And frankly, a city-sponsored recreational event with an appreciable risk of mass suicide seemed like a reasonable prescription. Since someone was going to die, better it be trained athletes in quest of a goal than miners wrecking their pickups. Besides, Perna thought, maybe the loss of a few adventurers could serve a greater good of medical research: Right after shaking Ken’s hand, Perna called a pulmonary specialist in Denver and suggested he use the race as a giant, open-air coronary lab.

To hell with that death and dyin’ noise, Ken thought. We ain’t falling-we’re fighting. To make that point, he’d brought a little surprise to the start of the first race. He could have christened the first Leadville Trail 100 with the typical starter’s pistol or air horn. Instead, Ken hauled out an ugly, old shotgun, the kind of heavy-hammered blaster the local outlaws used to rob the mining companies’ stagecoaches.

“Remember!” he shouted to his 45 runners. “You’re tougher than you think you are!” Then he aimed his shotgun right over the Climax mine and let ‘er rip.

Boom! As the blast echoed, Leadville’s future began trotting into the gloom. Ken put down the gun and went running after them.

Leadville’s ghosts must have cheered from the shadows. Because if the “Two Mile High City” is known for anything besides mining, it’s legendary badasses.

Located 38 miles south of Vail, in Central Colorado, Leadville is the highest city in North America, at 10,152 feet, and, many days, it’s also the coldest. In the 1800s, prospectors who’d risk anything were still stunned when they got this far and saw what lay ahead. “For there before their unbelieving eyes loomed the most powerful and forbidding geological phenomenon they had ever seen,” Leadville historian Christian J. Buys writes. A single slip on one of those switchbacks meant death. Something as simple as an ankle sprain could be fatal. But the toughest of the lot forged ahead and triggered not just a rush but “the richest, longest-lived, bawdiest phenomenon that America has ever witnessed.”

The richest man in early Leadville, Horace Tabor, was also the grittiest. A frontier grocer, he endured historic blizzards and desperate poverty while riding out two devastating cycles of claims and busts: first gold, then silver. His wife was even more iron-willed. After Horace lost their millions, his widow, Baby Doe, obeyed his deathbed request to hold on to his last property; she spent her last 30 years in a dilapidated shack at the mouth of the Matchless Mine, alone and impoverished, her body in rags and her feet wrapped in newspaper, asking help of no one.

Jesse James was drawn to Leadville, not just by stagecoaches loaded with gold and silver, but also by the wild, impenetrable mountains, which let him roam free and vanish. Doc Holliday lorded over the Leadville casinos and was often visited by his old pals, Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson. It should come as no surprise that the Unsinkable Molly Brown chose to make Leadville her home.

“Folks who live at 10,000 feet are cut from a different kind of leather,” Ken likes to say. Despite his shotgun séance with the spirits of Leadville, the truth was Ken had no clue if anyone really would be able to finish the race-hell, himself included. All he knew was how tough it was for even a donkey to run 22 miles in Leadville. It was his donkey, after all, that led to the idea in the first place.

In 1976, when Ken had just arrived in Leadville, he heard about the annual Boom Days burro race. You get a burro, load it with a 33-pound pack, and run behind it 11 miles up the Mosquito Pass trail, then turn around and run back into town. “Man, I’ve got to try that,” Ken thought. No matter that he knew diddly about burros or could barely run five blocks from his house to the town’s library. It was the same way when he started at Climax: He’d never touched a stick of dynamite in his life, but that didn’t stop him from setting off a five-pound bomb his first day on the job.

If it sounds cool, why not? That’s the teenage logic Ken has obeyed ever since, oddly enough, he stopped being a teenager. He became a burro racer in his 30s, an ultramarathoner in his 40s, hopped on a Harley in his 50s, a rodeo bull rider at age 60. Now, 66 years old, he’s spent time as a soldier, scientist, elk hunter, miner, state senator, GOP national delegate, and U.S. Senate candidate. The second half of his life seems almost pathologically manic, especially when you consider that he spent the first half pumping gas in a spit-chaw Okie backwater.

He was born in Shawnee, Oklahoma, and soon made it his life’s mission to get the hell out of Shawnee, Oklahoma. He married right after high school, then wiped windshields at his dad’s garage while his wife, Pat, was in college. As soon as she graduated and began teaching school, he did a tour in the Army, then got his biology degree from Oklahoma Baptist. His dream was to become a doctor, until he found out that medical schools were charging $1,500 just to apply-a dizzying sum in 1960s Oklahoma. He bitterly resented feeling jackrolled by the med school mafia, so he said to hell with medicine. In the heat of that disappointment, he convinced Pat to load their car and move to the nearest big city on the map: Denver. “Man, it was a revelation,” Ken says. “Bars on every corner, a horse track-Sin City! And I was loving it.” In the Flower Power afterglow of the early ’70s, his hillbilly accent and striking resemblance to Johnny Cash came across as True Rustic, and Ken found a way to make it pay. “I got a job selling insurance, and me talking like a hick, I made a killing.”

That first year in Denver, Ken and his wife agreed the city was no place to raise their newborn son, and they moved to Leadville. He signed on with the Climax mine. It was making a fortune, he’d heard, and spreading it around. Mining paid so well, it became virtually the only job in Leadville: Plumbers, carpenters, and accountants all left their trades and hired on at Climax, until getting a toilet fixed required a long-distance call and a two-day wait. Of 4,500 Leadville residents in 1978, 3,000 were working in the mines. Besides, big bucks for blowing up boulders sounded cool to Ken.

For decades, Leadville had been sitting on something better than a gold mine-a “moly” mine. Molybdenum is a mineral that strengthens steel, so when you’re building tanks, Uzis, or battleships, you need moly by the truckload. And if there’s one product in the world that will never go out of fashion, it’s killing machines. Leadville had 75 percent of the market.

“First night underground, the outgoing shift boss tells me, ‘We left an eight-pound bomb in car five.'” What’s that? Ken recalls thinking. He jumped right in, though, and soon felt at home with more dynamite under his coat than a suicide bomber.

The market that could never take a dive took a dive in the early ’80s. Moly production in Eastern Europe had ramped up, and prices were plummeting. With Reagan talking arms treaties with the Soviets, Climax was done. The company never closed the mine for good; it just sent everyone home and waited for a chance to get back into the game. Two decades later, it’s still waiting.

“One thing I’ll never forgive the damn company for,” Ken says. “By the time you get into your digging clothes, with the self-rescue belt, the steel-toe boots, the helmet, it takes a half hour. And that’s when they tell us we’re laid off. I had to go back down to the locker room and spend a half hour taking that shit off, thinking about how I’m going home to tell my wife and son that Daddy doesn’t have a job anymore.”

“It’s not hopeless,” said an economic developer Leadville hired to come up with an emergency strategy. “You’ve got two things going for you: the mountains and Leadville’s heritage. What you’ve got to do is use them in a way that will make visitors stay overnight.”

Well, no shit. But how? Leadville saw every other post-industrial city in America grabbing for the same life ring: They were all trying to abracadabra themselves into vacation spots. Leadville was tempted to resuscitate the gaming business of its wild yesteryear, but the townsfolk voted it down. Slots would bring big money to the city, no doubt, but it wouldn’t be their city; what was the point of saving Leadville if it was no longer the Leadville they loved? They didn’t want to spoil Leadville’s old-time, Main Street character, nor live off human gullibility and addiction. The irony was bittersweet: Leadville had once been the wildest shoot-’em-up city in the West, and even as recently as the ’40s, State Street was so notorious for knife fights and gynecoccal prostitutes that soldiers from Camp Hale were forbidden to go near it. But Leadville changed all that. Flophouses were converted to family homes, brothels became cafes, and Leadville became a safe and neighborly place for miners to raise their kids. Backsliding now would have been another form of defeat.

Rejecting gaming was courageous but potentially fatal. Leadville sure didn’t have money to build any fancy convention center or any kind of touristy draws. It could barely pay the economic developer who suggested such things. Besides, who’d visit a place where every sea-level dweller has a headache the first three days in town?

Ken’s master plan came courtesy of his donkey, ol’ Mork. Ken needed a pair of running shoes to get in shape for the burro race. He figured he’d splurge on a pick-me-up and drive the two hours to Denver for a pair of those fancy Nikes with the waffle soles and yellow swoosh. Browsing the racks, he bumped into a guy, Jim Butera, who had a notion of a race from Vail to Aspen. Another guy in California had done something similar eight years earlier.

It would be a nice event for Aspen, Butera figured. Aspen had a resident community of endurance athletes and a crack search-and-rescue operation on hand for ski season, but most of all it was rich enough to bankroll a likely money-loser of an event. Ken knew another reason the race was better suited for Aspen than for Leadville, but he didn’t share it with Butera: Miners despise tourists. To them, this would be some dumb-ass lark for pussyfooting yuppies.

On the other hand, wasn’t this just what the economic developer had recommended? Use the mountains and Leadville’s heritage. Besides, Leadville at its heart was a frontier village, with the same determination and underdog spirit as the ultrarunners. What was a miner, after all? A man trying to conquer a mountain.

“Screw Aspen,” Ken snorted. “Let’s do it in Leadville.” Besides, it sounded kind of cool.

Here’s how impossible it is to run from Leadville to Winfield and back: Dean Karnazes, the ultramarathon cover boy who’s run 262 miles nonstop, can’t do it. “We call him O-fer,'” says Ken. “He’s tried it twice, and he’s O-fer-2.” Laurel Myers, a marathoner from Aurora, has tried it 19 times and never succeeded.

Yet here’s how possible it is: Gary Johnson, the 46-year-old former governor of New Mexico, has done it. So has millionaire Steve Fossett, at age 47. King Jordan, the deaf, 62-year-old president of Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., has done it-ten times. “I told O-fer we got senior citizens up here who can kick his ass,” Ken says. “Musta hurt his feelings. He’s never been back.” Ken never thought the Leadville Trail 100 would turn out to be such a counterintuitive conundrum that it seems to favor the old over the young, the super-determined over the super-fit.

Race Day begins around 3:30 a.m., when the runners gather outside the Leadville Courthouse. The scene is a blend of carnival and locker room. Leadville’s fire trucks park near the starting line; their flashing lights, along with the streetlights and the runners’ flashlights, cut throught the darkness. The pungent musk of tiger balm mingles with bug spray, sunscreen, and nervous farts. Screams of laughter erupt in the distance from partiers who’ve stayed up all night to see the runners off. Standing at the starting line, runners hear voices from the dark sidelines describe how vigilantes used to lynch claim-jumpers right here-“right where you’re standing”-and leave their corpses to rot from the ropes.

At a few ticks before four, Mayor Bud Elliott steps up. He lifts a shotgun. (Last year, he switched to a new gun because the old one’s tricky hammer nearly took off his thumb, twice.) Bud eyes the clock. Three…two…. The race director shouts a final warning: “If you drop out, you must get your wristband cut off!” Otherwise, they won’t know who’s still out in the woods. Fewer than half the runners will make it back to Leadville on their feet.

Blam!

“Nothing will happen for the next 10 or 12 hours,” a Leadville contestant once wrote of this moment. “Then we will engage the beast.” The first miles are heaven. It only takes a few minutes for your body to warm and nerves to settle, and once they do Leadville is the greatest place to be, at the greatest time to be there. When you hit the 10-mile mark, the sun is rising, the snowy peaks are glowing, and Turquoise Lake is living up to its name. It’s all so magnificent, you forget it will be late tomorrow morning before you get back.

May Queen Campground is 13 miles in, and as you approach this first aid station you suddenly hear “Whoop-whoop-whoop!” and see men waving six-shooters and women flouncing in gowns and corsets. These are the “Leadville Raiders,” a group of locals who like to dress up in old-time gear. “When Ken first came looking for volunteers, it was a real depressing period,” says John Cirullo, a Realtor whose business seemed doomed. “But every club in town stepped up, before we even knew the impact the race could have.”

“I should’ve known,” Ken acknowledges. “Miners are people of extremes. You tell anyone else you want to run 100 miles, they call you nuts. Tell a miner, he’ll ask if you need a hand.”

Up and over 11,000-foot Sugarloaf Pass, the racers run on down to the 40-mile mark at Twin Lakes, where Doc Perna and Cindy Corbin, the obstetrics chief, will be stomping their feet for warmth in a dirt-floored garage, as they have every year for 23 years. Doc likes to check everyone out here, before they ford the river and hit Hope Pass, which one runner describes as “a boulder staircase shooting straight up to the sky.”

“We’ve recommended a few people get out of here,” Perna says. “A few for chest pains. One guy was coughing blood.” The hotels in Leadville are full for race weekend, but so is the emergency room. “The hospital makes a ton of money,” Ken happily points out. Since the inaugural race, Leadville has added four more endurance challenges: the Leadville Trail Marathon, the Leadville 10k, the Leadville Trail 100 Mountain Bike Race, and the Leadville Silver Rush 50-Mile Mountain Bike Race, all on separate weekends throughout July and August. Add the Leadville Trail 100 Training Camp in June and the surprisingly competitive burro race during Boom Days in early August, and Leadville’s businesses (and paramedics) are humming all summer. The first race drew 45 contestants; now, however, about 450 runners show up at the starting line, with 500 being the cutoff.

Though no one in Leadville seems to track the local economy and the race’s effect on it, Mayor Bud Elliott says it’s brought “millions of dollars into this community. I’ve talked to visitors who think the town is here because of the races, not because of mining. They’ll say, ‘Oh, you have mines here, too?'”

“It’s an unstudied but very noteworthy phenomenon, the kind of economy you can build around just the right race,” says Dr. Raymond Sauer, a Clemson University sports economist. “Look at Daytona, the Kentucky Derby. You can’t take a cookie-cutter approach, though. Just because one town does it, that doesn’t mean you can do the same thing. The key is, the event has to have a special resonance-it has to make people feel they’re participating in an initiation ritual and becoming a part of the place.”

On the far side of Hope Pass, runners get a chilling look down on the Leadville that might have been. Far below is the turnaround point, in the ghost town of Winfield. Ken didn’t exactly plan the symbolism, but even after 12 exhausting hours of running, it’s powerful and apparent: Before heading back to the warming cheers and pretty pastel Victorians of Leadville, runners have to absorb the silence and ruin of another post-boom town.

The Winfield turnaround is also where Ken nearly cooked his own bacon in the first race. Near Winfield he lost his way and wandered Hope Pass until finally flagging a pickup. In the open back, he rode back to the Twin Lakes first-aid station. He suffered severe hypothermia. Nearly everyone suffered a similar fate. Only 10 of the first runners finished, meaning 4 out of 5 had to be pulled from the woods.

Make it back up the boulder staircase a second time and you’re treated to a bizarre welcome on the far side: an encampment of woolly llamas and even woolier partiers, who camp through the night like a tribe of friendly yetis. “Hope Pass is a bad son of a bitch on a good day,” Ken says. “If it weren’t for those llamas, we’d have lost a good many lives.”

Before the first race, Ken didn’t have the nerve to ask anyone in Leadville to staff an aid station at the top of Hope Pass; it would be too cold to tough it out for 30 hours, especially since it’s the rare August night that passes without a dousing of rain or snow. But a group of llama owners decided on their own to hike up and camp out, just in case anyone was in trouble. Since then, “The Hopeless Crew” has grown to 80-some llamas and owners who hang in through the night, dispensing first aid and hot soup.

If you get down the mountain, past the rustic log lodges of Twin Lakes while the sun is still up (and that’s a hell of an if), you’re psyched, because at least you have daylight to ford Lake Creek before heading back up into the ultimate meatgrinder: Sugarloaf. “I came here thinking I was going to blow this course away-until I got to Sugarloaf,” says Miles Krier, who’d grown up running the deep canyons of northern California. “I’d been running ultras for 11 years, but Sugarloaf on the way back is one of the most brutal climbs I’ve ever done. It’s so steep, so long, the temperature is dropping…”

May Queen Campground, consequently, should smell like victory: You’ve gone 87 miles; you’ve survived a long night in the woods with no company but your flashlight and rasping breath. The sun is warm and you’re 13 miles from triumph. Curiously, though, May Queen is where some of the most experienced runners drop. Mary Moore, winner of the shorter Leadville Marathon in 2002, gave up here. So did Craig Robertson, who’s run dozens of long races across the country, but only finished Leadville four of eight times. “Cut the band off me!” Craig demanded one year, lifting his wrist as he stumbled into May Queen.

Craig was so nauseous, the idea of one more step made him wretch. Miles Krier tried to quit at May Queen, but after a glance inside the medic’s tent full of weeping, moaning, bleeding, vomiting casualties, which he calls “The House of the Damned,” he instead limped on to Leadville.

Awesome! You’re back in Leadville, your friends are screaming, you’re minutes from pancakes and bed, but you’ve got one more obstacle: time. As the clock ticks down, Mayor Bud picks up his shotgun and carries out his cruel annual ritual: At the stroke of 10 a.m., 30 hours after the start, with his back to the finish line and the runners struggling toward it, Bud fires the shot that ends the race. If you’ve breasted the line, you’ve done it! Congratulations, you’ve won yourself a belt buckle. It’s silver with “LT100” written in gold lettering. If you’re late, even by a minute, you haven’t.

“It hurts,” Ken admits, and he knows just how much: He’s run every single year, but for the last six the shotgun has beaten him to the finish.

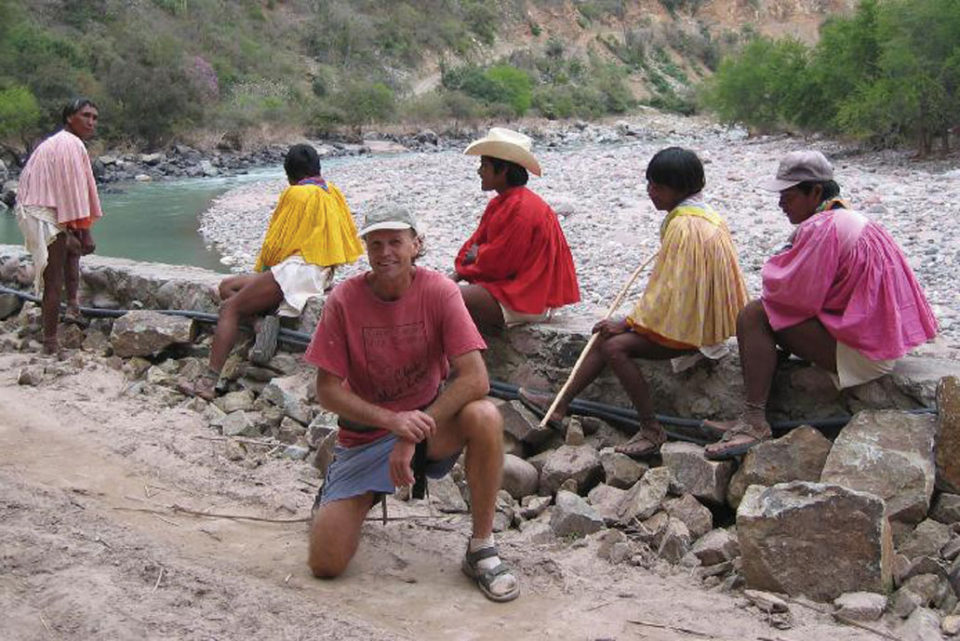

The only runners who ever really mastered the race are the guys who appeared one year in loincloths, pirate blouses, and sandals they’d made from scraps of tire scavenged from the Leadville junkyard. They were Tarahumara (pronounced Tara-Mara), a near-mythic Indian tribe considered the world’s greatest-and most reclusive-distance runners. Word of the race had reached them at their home in the bottom of Mexico’s most impenetrable canyons, and lured them out to compete for only the third time in 67 years.

“Hola!” Ken greeted them. He offered the phrase he’d been taught by the high school Spanish teacher for, “Have a good race!” The Tarahumara remained silent. Few of them spoke Spanish. One of the other two times that the Tarahumara had left the canyons to compete, at the 1920 Amsterdam Olympic marathon, they finished in the middle of the pack and were amazed that the race was over already. The Tarahumara are used to drinking cactus moonshine all night, then waking up to run 150 miles while kicking a small wooden ball.

In 1992, that first year they showed up in Leadville, all six Tarahumara dropped out, apparently victims of culture shock. They’d had been escorted to Colorado by a self-styled “friend of the canyons,” an Arizona explorer named Rick Fisher. According to Ken, they’d been poorly prepared. The Tarahumara were pointing their flashlights straight up like torches and were acutely uncomfortable in the Converse sneakers Fisher provided.

But in 1993, the Tarahumara came roaring back-in their own gentle, silent way, that is. This time, Fisher had them in running shoes from Rockport, a race sponsor. But at the last minute, the Tarahumara went scavenging in the Leadville junkyard and lashed together homemade huaraches from tire scraps. And like that, running nearly barefoot and eating only ground corn from a small sack around his neck, 55-year-old Victoriano Churro came in first, followed hard behind by two fellow tribesmen in second and fifth.

The media took note. Mythical Indian runners in loincloths defeating some of the most scientifically trained athletes in the world? A near geriatric winning one of the world’s toughest footraces? Now that’s a story! Suddenly, Leadville was a media darling: The New York Times, Runner’s World, and ESPN announced they’d be on hand for the ’94 race.

“The Tarahumara put Leadville on the map,” says Micah True, a wilderness guide and ultrarunner from Nederland who paced one of the tribal runners over the strange terrain in the 1994 race. During the long, silent run, Micah and one Tarahumara in particular, Martimiano Cervantes, bonded so tightly that later Micah practically moved in with the tribe. Micah learned that violence is virtually unheard of among the Tarahumara. So are prostitution, obesity, theft, child molestation, domestic abuse, and heart disease. There had to be a connection, Micah thought, between the Tarahumara’s superhuman virtues and superhuman endurance. If there is a master race, he thought, maybe they’ll be the humblest and they’ll carry their message on foot-like another guy in sandals long ago.

But that doesn’t mean they ain’t some tough hombres, Micah realized as they ran through the night. Up ahead, a 25-year-old Tarahumara named Juan Herrera was chasing down ultra sensation Ann Trason. Herrerra not only won but chopped 25 minutes off what was then the Leadville record.

It was one of the greatest ultra showdowns of all time, and Leadville’s crowning moment. Two Old World cultures-unbending miners and unbeatable Indians-had just taught the New World a lesson that’s hard to glean from professional sports and even from the amateur Olympics: that sports aren’t about riches, but rather about the richness of human potential, tested and realized.

Too bad the lesson only lasted half an hour. Right after Herrera’s victory, Ken says, Rick Fisher demanded that Rockport cough up $5,000. “He held Rockport hostage [so the company could] use film of the Indians,” Ken says. To avoid a PR mess, Rockport paid-even though no winner has ever gotten prize money at Leadville, just a little something to help them hold up the pants. Well, bullshit on that, Ken decided. He began enforcing a rule that every runner fill out and sign their own application, which ruled out the illiterate Tarahumara. Meanwhile, Fisher, who could not be reached to comment for this story, went on the rampage, accusing Leadville and three other ultra races of conspiring against the Tarahumara.

A showdown between the Tarahumara champ and ultrarunning’s current champions would draw more TV cameras to Leadville than it’s seen in a decade. But the Tarahumara won’t be there. The only trace of the tribe will be whispers of speculation about why they left and what could have been.

“Hear that?” Ken asks.

The two of us stop snowshoeing for a sec, and once our crunching footsteps fade away I pick up the whining bark of coyotes among the junipers. It’s cold for March 27, and nowhere colder than Leadville, which CNN is declaring the chilliest city in the nation at 5 degrees. Never mind that a serious squall is brewing, Ken wants to sneak in a fast hike into the mountains to show off Hope Pass.

Along the way, we pass a giant herd of elk. If we’re lucky, Ken says, we may see bighorn sheep. What we don’t see are casinos, or fake-Swiss time-share villages à la Vail, or even a Starbucks. The vast cement shopping malls of Silverthorne are an hour away by car, but a century away in spirit. Bit by bit, Leadville has been plumping back out. It’s changed, of course-the grammar school is predominantly Latino, and there are more Mexican restaurants than steak houses-but in the ways that matter, it’s remained the same, soulful and simple. If you need a bed for the night, you talk to Miles Krier, who once shook Ken’s hand and said, “Sir, I like your town and respect your race, but I’m never coming the fuck back.” Now Miles owns Leadville’s AnyTrail Lodge. If you want a triple latte, see Milly Austin, who abandoned her lab-manager job in Alaska and degree in cellular and molecular biology to open Cloud City Coffee House. Craig Robertson can build your house. He left a great teaching job and a gorgeous girlfriend in San Antonio to become a Leadville carpenter. And Mike Hickman, who’d been a CPA in Kansas City before running Ken’s race, is now a local county commissioner. Shoot, now Leadville’s even got itself a screenwriter, David King, who came here from L.A. These are all people who visited for a race but stayed for the community they found. They represent a future that without the race might not have been. Because of them, because of the race, because of Ken, Leadville’s indefatigable legacy will remain rock solid for at least another generation.

For the first time in a long while Ken has time on his hands. After he got laid off from the mine, he packaged his howdy-partner charm and acute intellect into a successful run for state Legislature in 1986, followed by a seat in the state Senate. He lost an underdog race as a GOP candidate for U.S. House of Representatives in 2002 (“Got m’butt whipped”), but returned home to Leadville a well-liked and charmingly idiosyncratic Republican who dressed like Buffalo Bill and was simultaneously pro-union, pro-gun, and a pushover on gay rights (“What folks do in bed ain’t my business”).

Now he’s back to thinking about his race full time. Applications are down for this year’s event on August 20. Where there used to be only four 100-mile races in the United States, there are now more than 30. Competition has bled away some of Leadville’s runners, and Ken has been getting heat to make some changes. Matt Carpenter, the country’s greatest mountain runner and a serious contender for a Leadville win this year, thinks the race needs to get more corporate and offer prize money. Micah True thinks the race is already too corporate. (Micah was so moved by his race with Martimiano that he’s started his own alternative ultra down in Tarahumara country in the Copper Canyons of Mexico, and is known among the Tarahumara as Caballo Blanco-“The White Horse”).

Huffing up Hope Pass, I hear Ken sigh. It’s been 23 years, and he’s still explaining what this race is about. “The kind of changes people talk about, it’s always about treating some runners differently than others,” he explains. “I’m going to resist that kind of elitism and make damn sure everyone gets treated the same.” See, for Ken, the race has never been about winners and losers, champs and also-rans. It’s about soul and spirit and survival. Which, after all, is the true essence of sports-the true essence of Leadville. The great gold barons went bust or moved on. Same with the great runners-every few years, someone takes the crown and then moves on. That’s why, frankly, the old miner that is Ken Choulber could give a crap who wins; he admires most the guy dragging himself around Turquoise Lake with blood in his shoes and a few precious ticks left on the clock.

Ken heard some great news recently: Because of the surge in defense funding, the price of moly has been rocketing way past the Climax mine’s old break-even point of $3 a pound. If it holds up around $25 a pound for much longer, the mine may open again.

And if it doesn’t, well, “I wonder how hard it is to snowshoe a hundred miles,” he says. A winter race, doesn’t that sound cool?

Christopher McDougall writes for Esquire and The New York Times Sunday Magazine.